Chaoskampf, Complexity and the Twisting Snake in William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job

Blake's Job is widely seen as illustrating an apocalyptic transformation of the self, but there are hints too of an acceptance of the role of chaos not only in God's creation, but in his own.

Contents

Patient Job, militant Job

Entering the mind palace of theodicy

Some see heaven, some see hell

Blake’s vision of Job

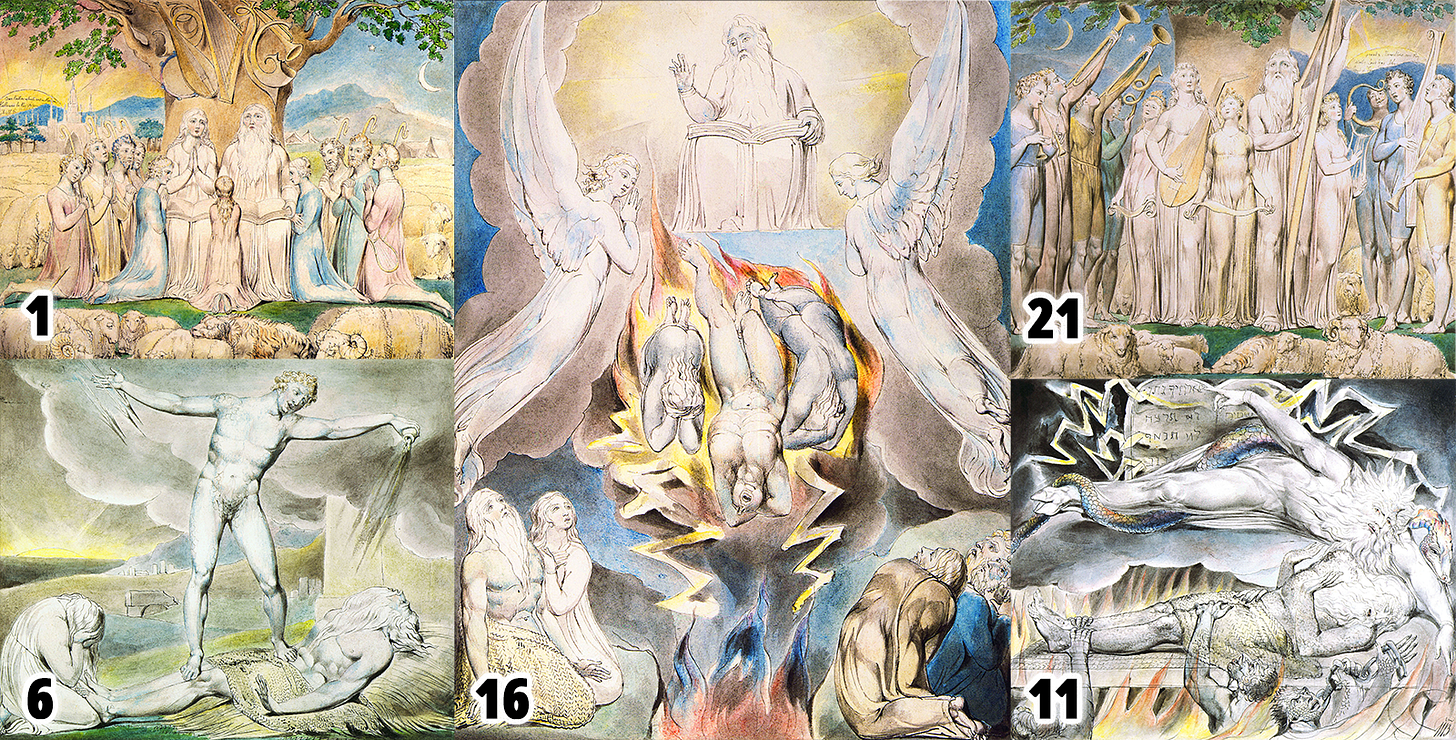

1: Job and His Family (ϰ)

2: Satan Before the Throne of God

God and his allies on Mount Zaphon / Zion

Ancient of Days

3: Job's Sons and Daughters Overwhelmed by Satan

Powered by wind

4: The Messengers Tell Job of His Misfortunes

5: Satan Going Forth From the Presence of the Lord and Job's Charity

6: Satan Smiting Job with Boils (ϰ)

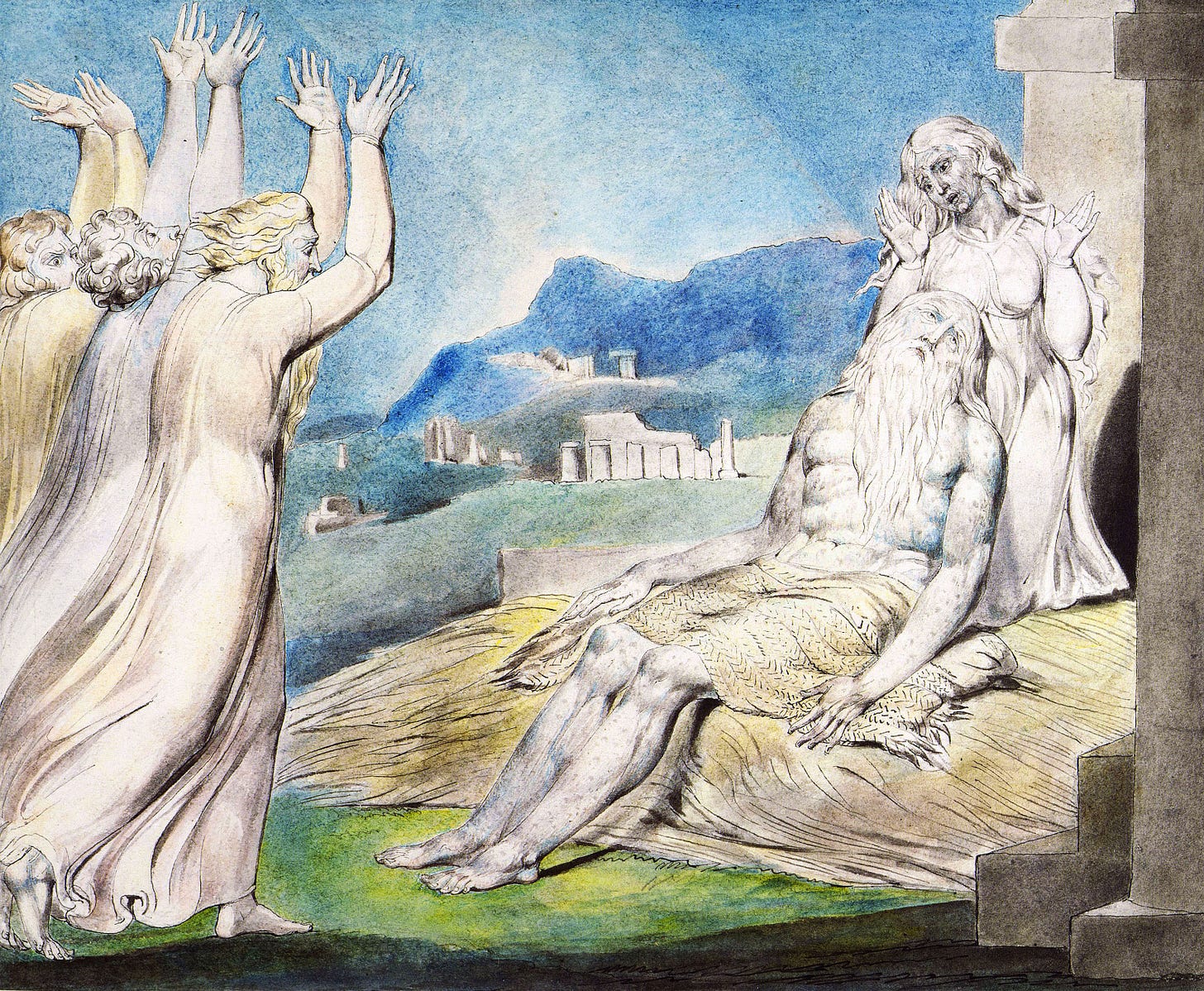

7: Job's Comforters

Friendship energy

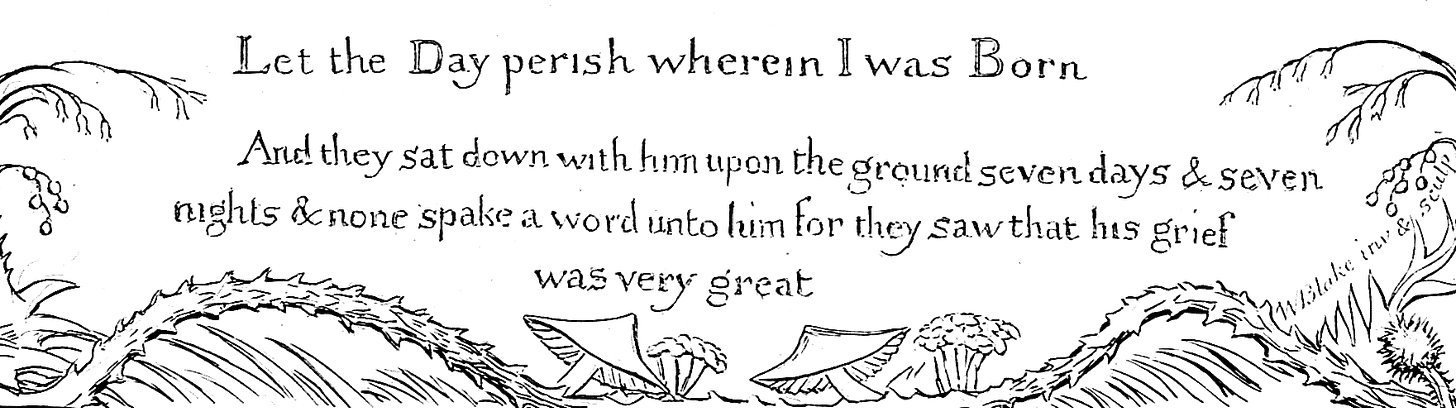

8: Job's Despair

A song of annihilation

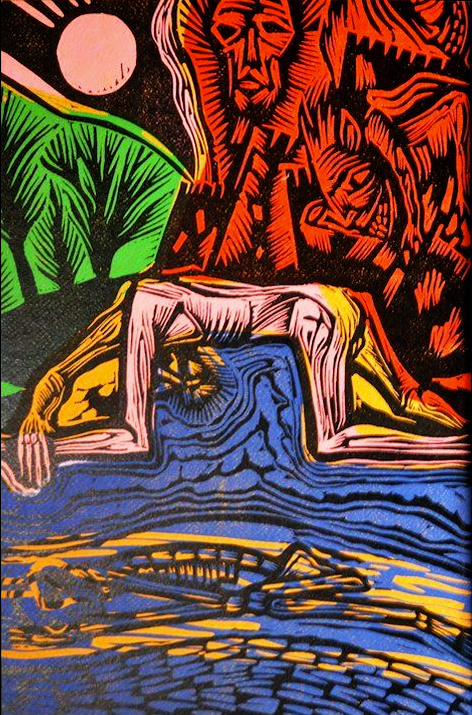

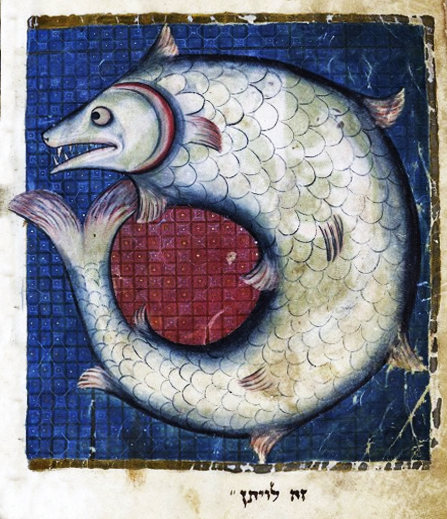

Leviathan, the twisting snake

9: The Vision of Eliphaz

Nobodaddy’s remainder

The uses of suffering

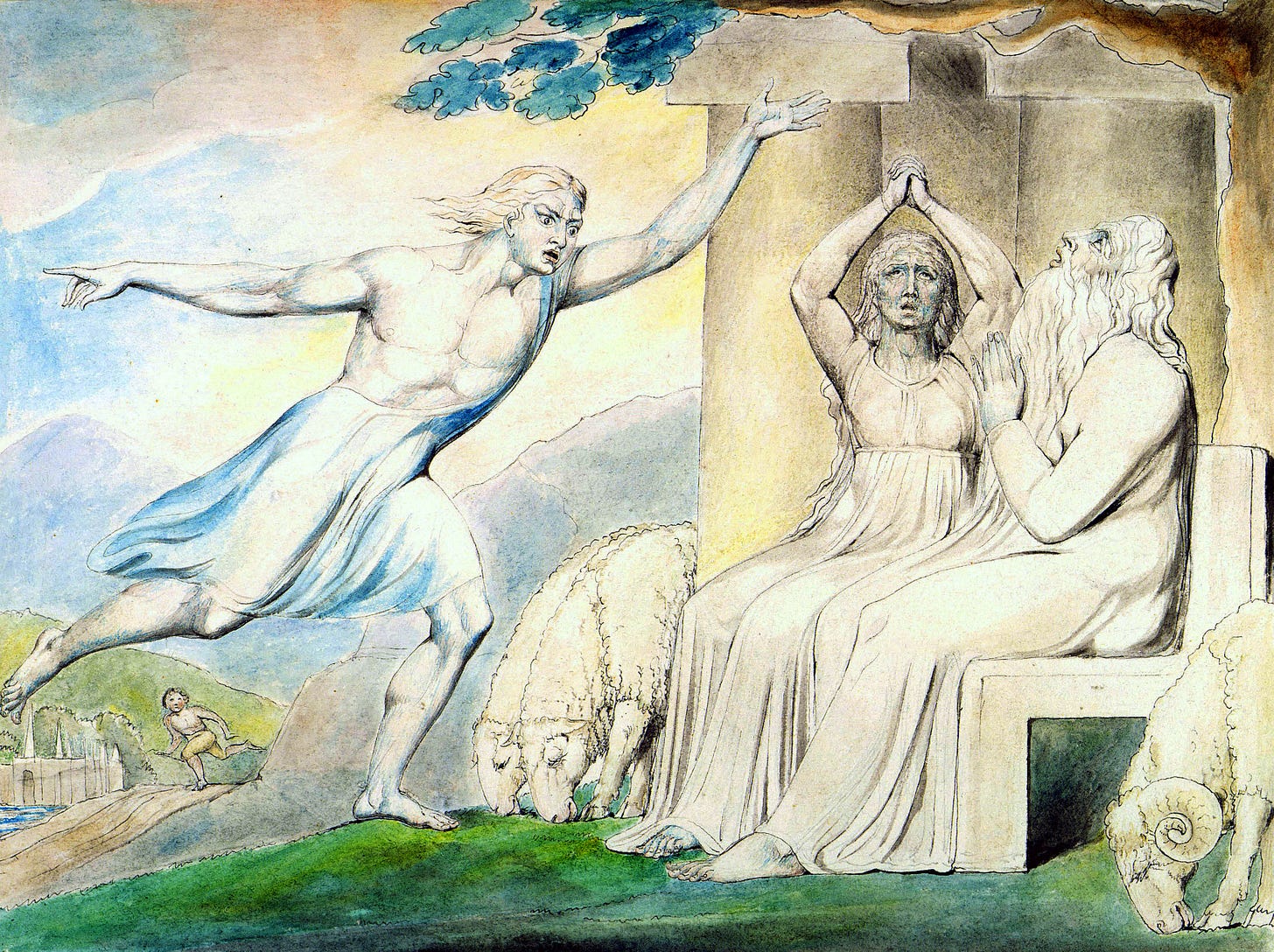

10: Job Rebuked by his Friends

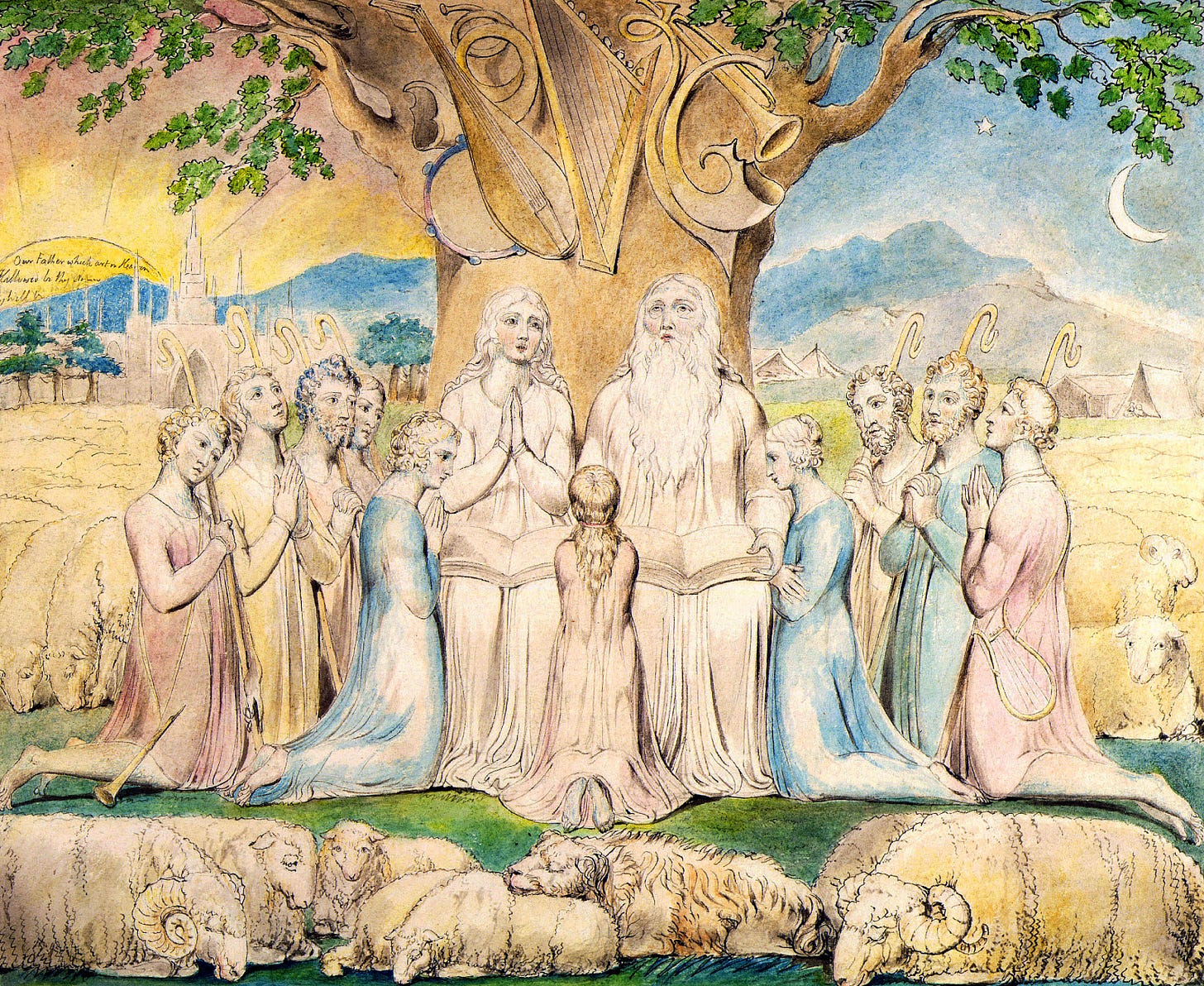

11: Job's Evil Dreams (ϰ)

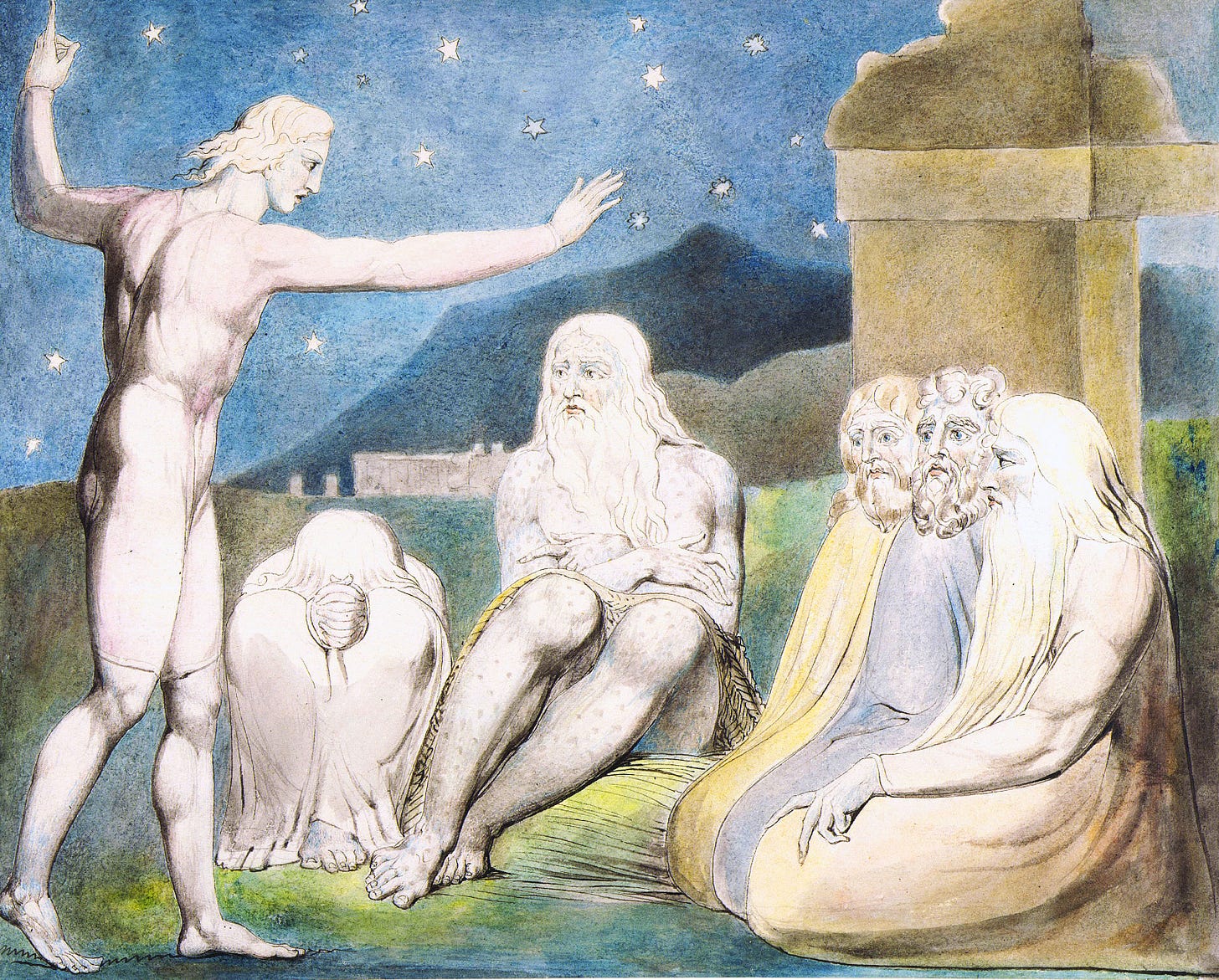

12: The Wrath of Elihu

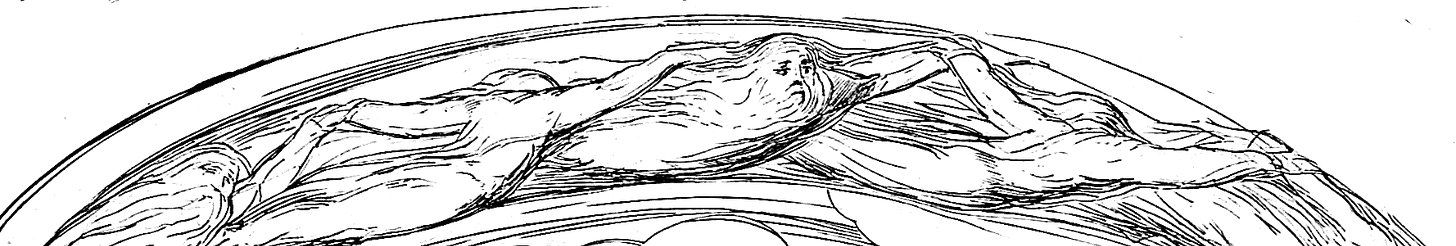

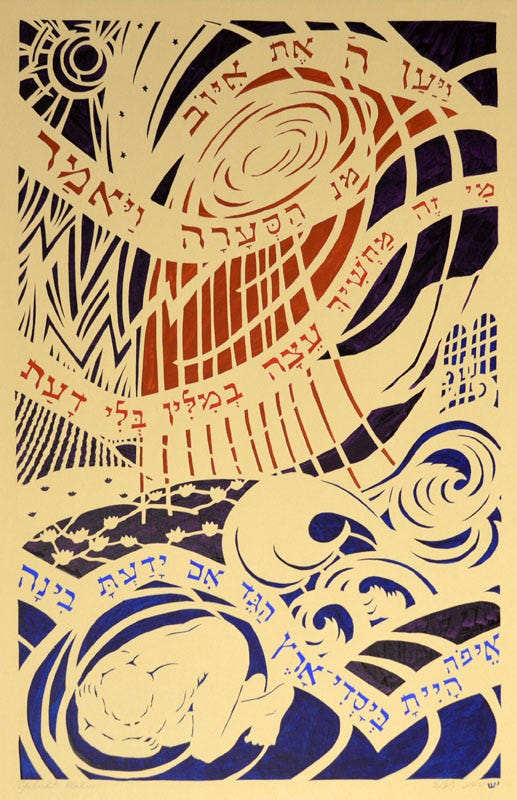

13: The Lord Answering Job Out of the Whirlwind

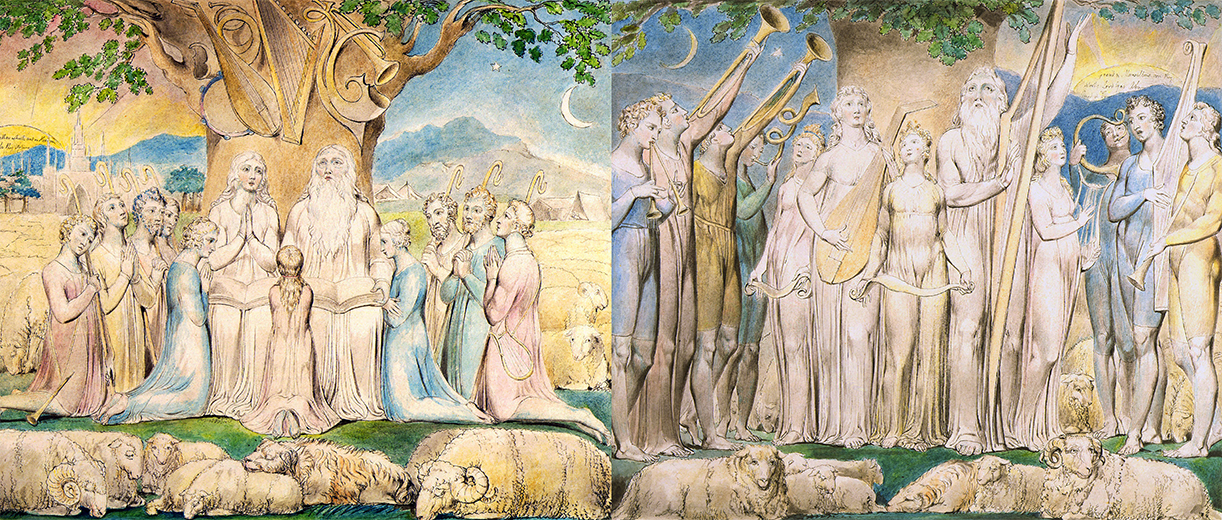

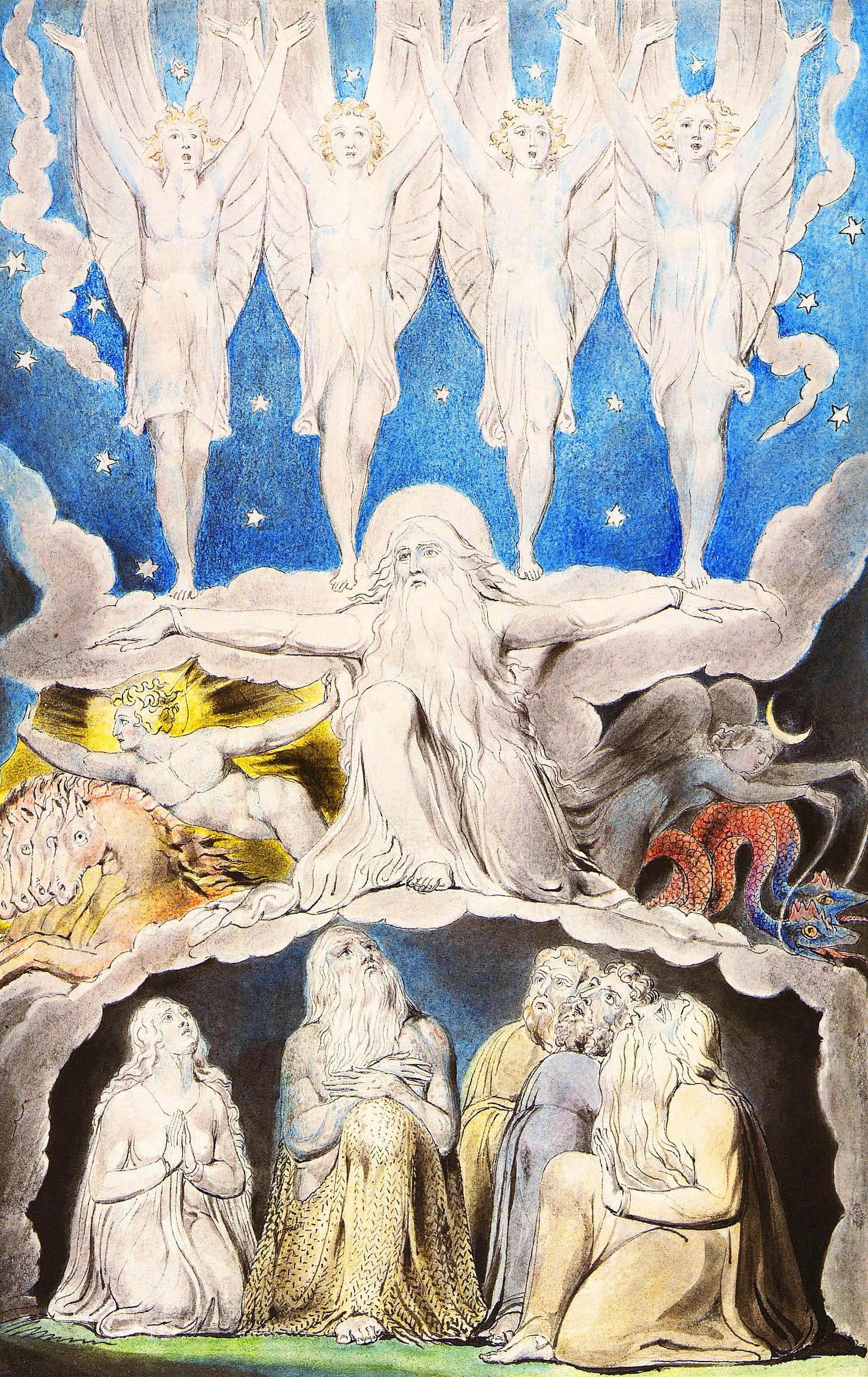

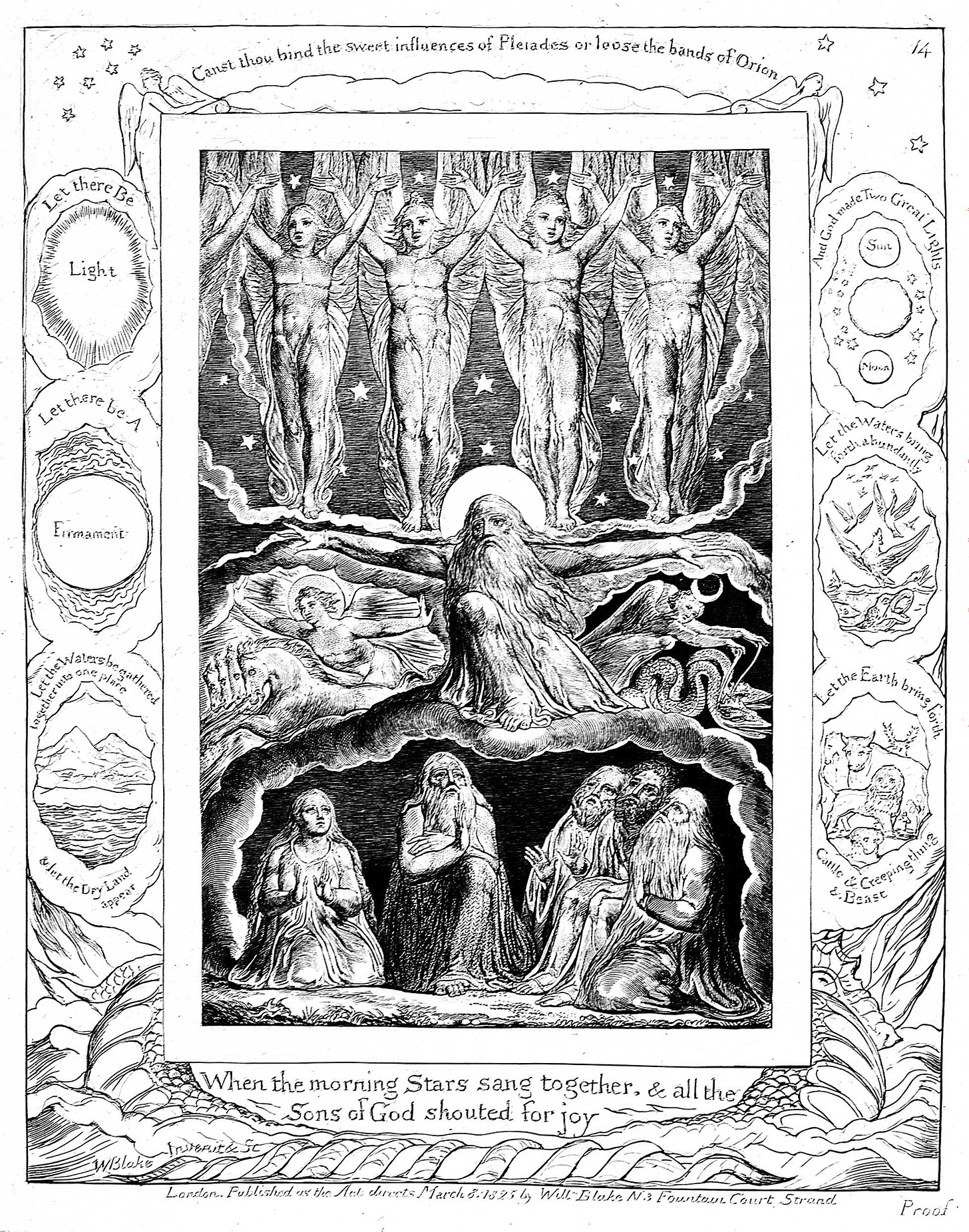

14: When the Morning Stars Sang Together

The Mount of Assembly

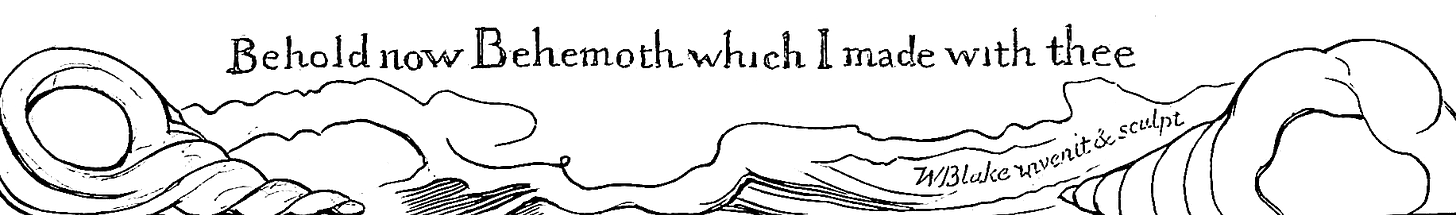

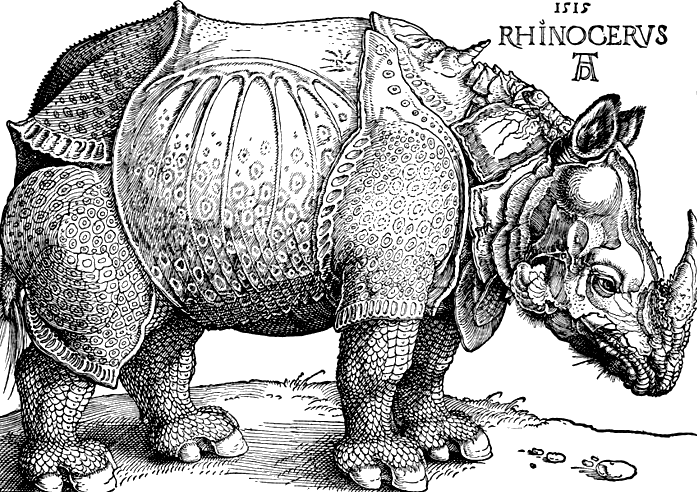

15: Behemoth and Leviathan

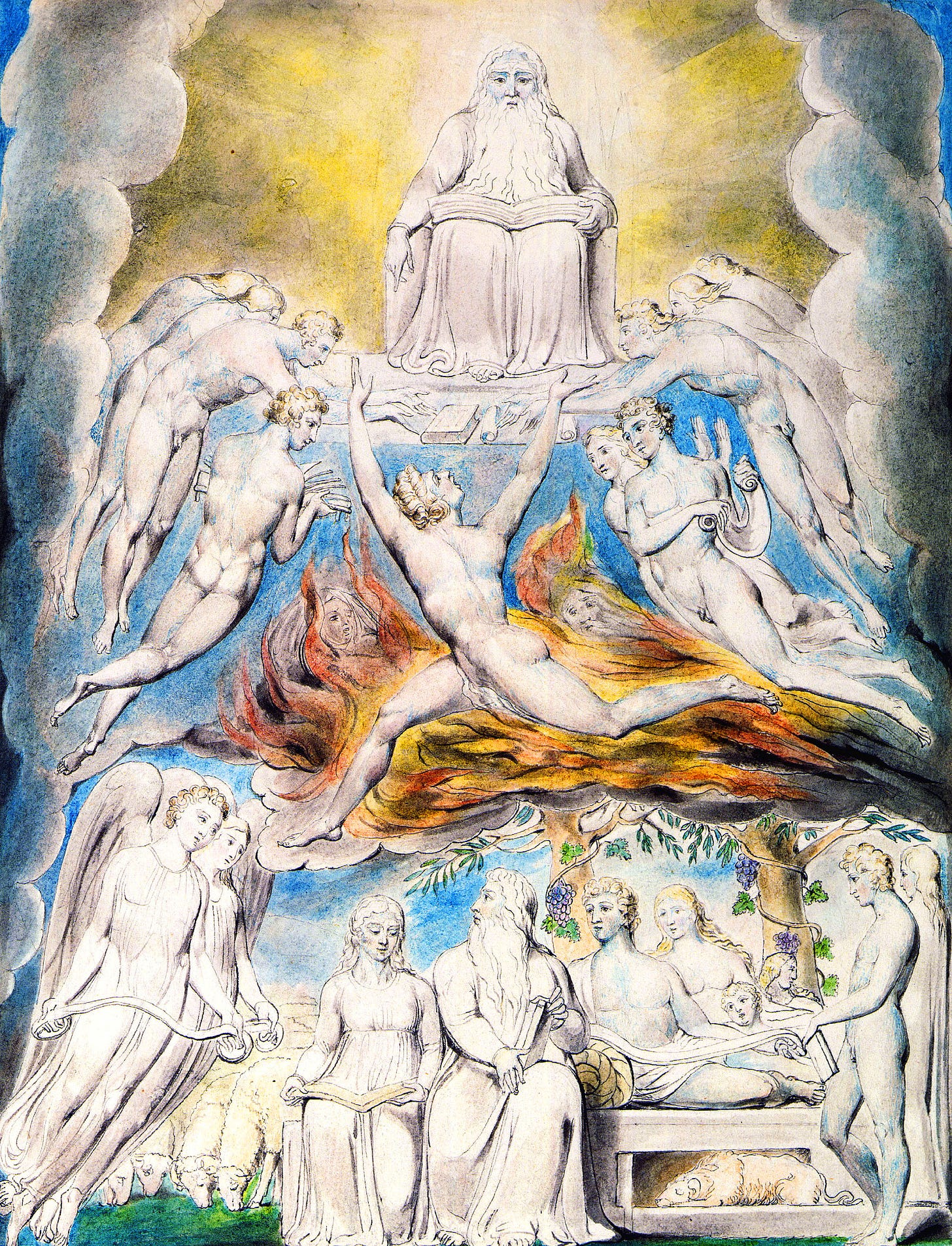

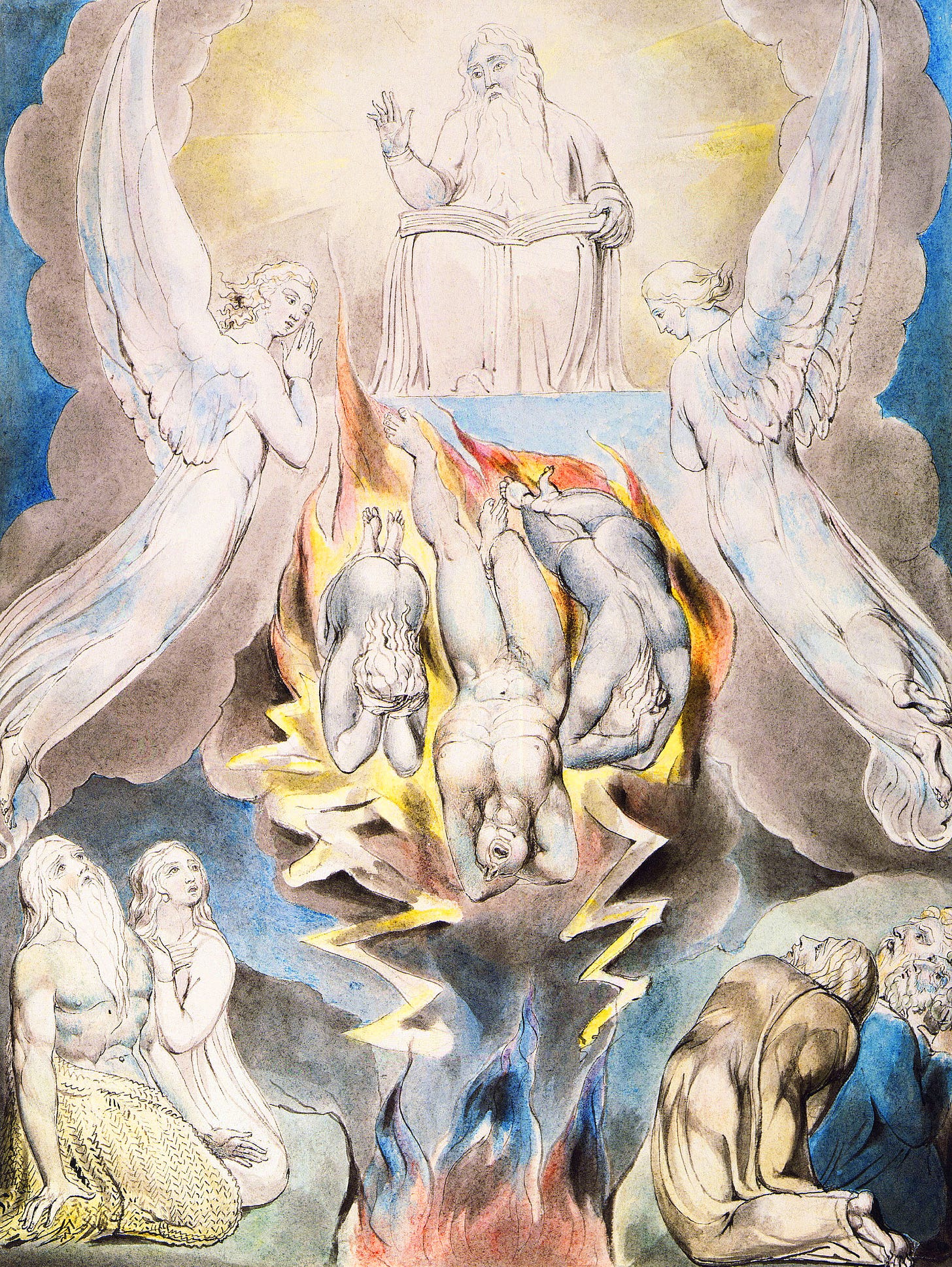

16: The Fall of Satan (ϰ)

17: The Vision of Christ

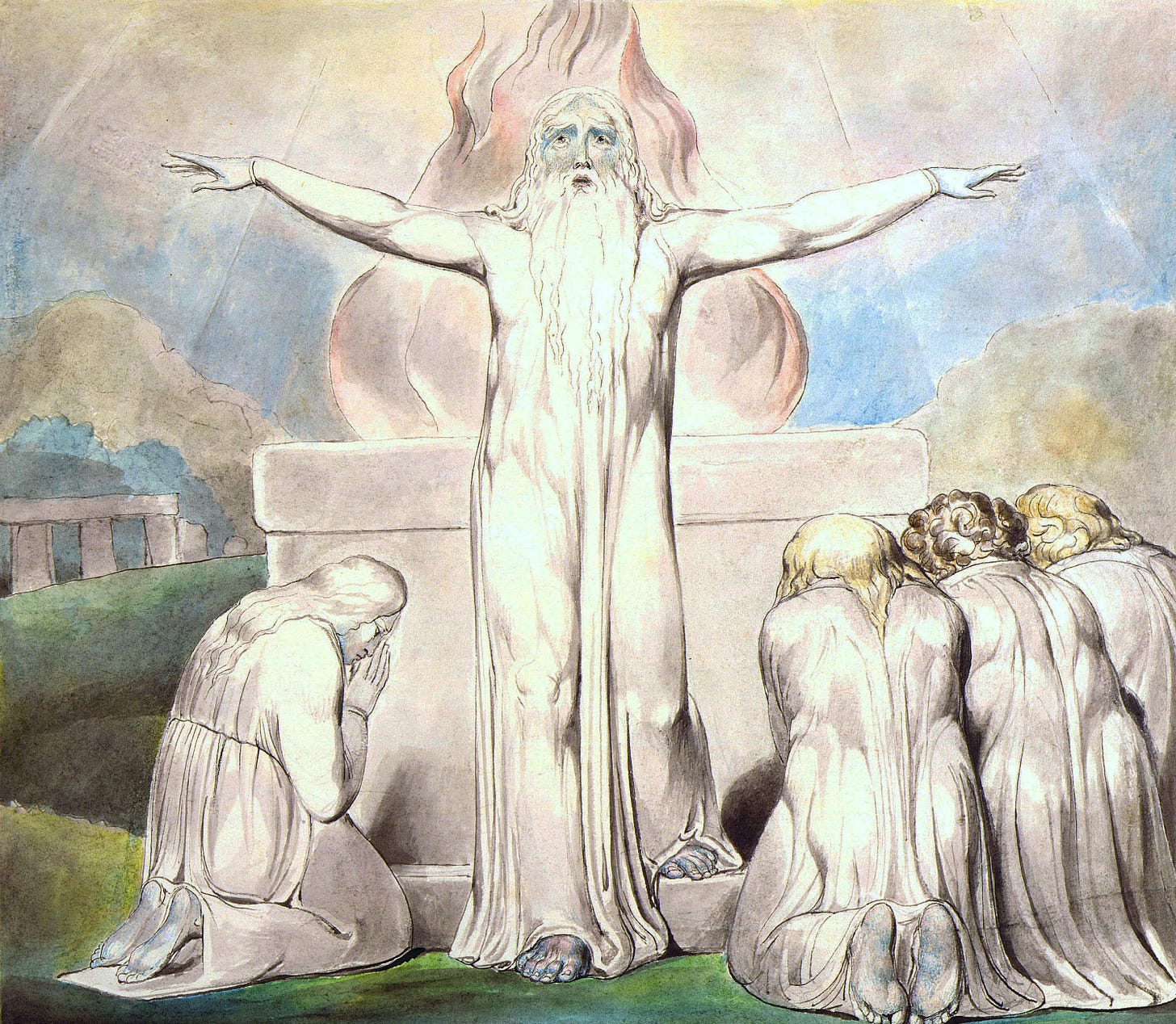

18: Job's Sacrifice / Job Praying for his Friends

From theodicy to solidarity

19: Every Man Also Gave Him a Piece of Money

20: Job and his Daughters

Art alignment

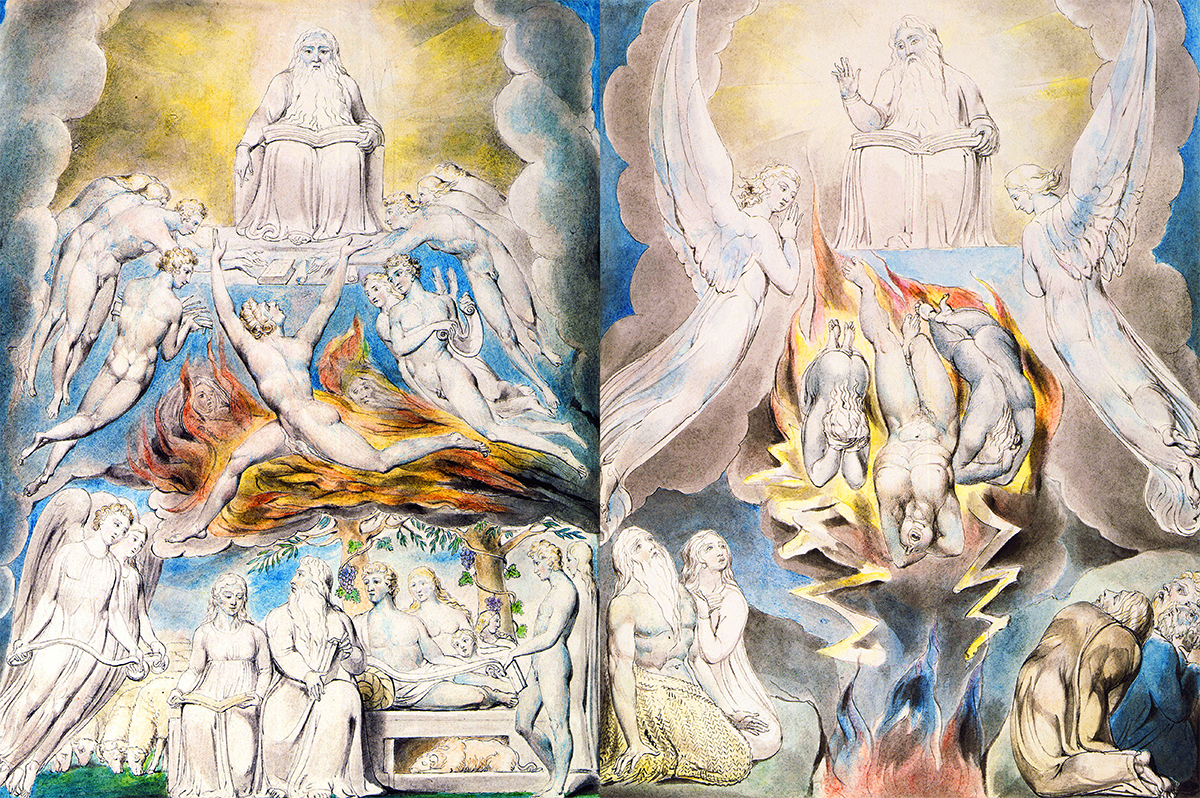

21: Job and His Family Restored to Prosperity (ϰ)

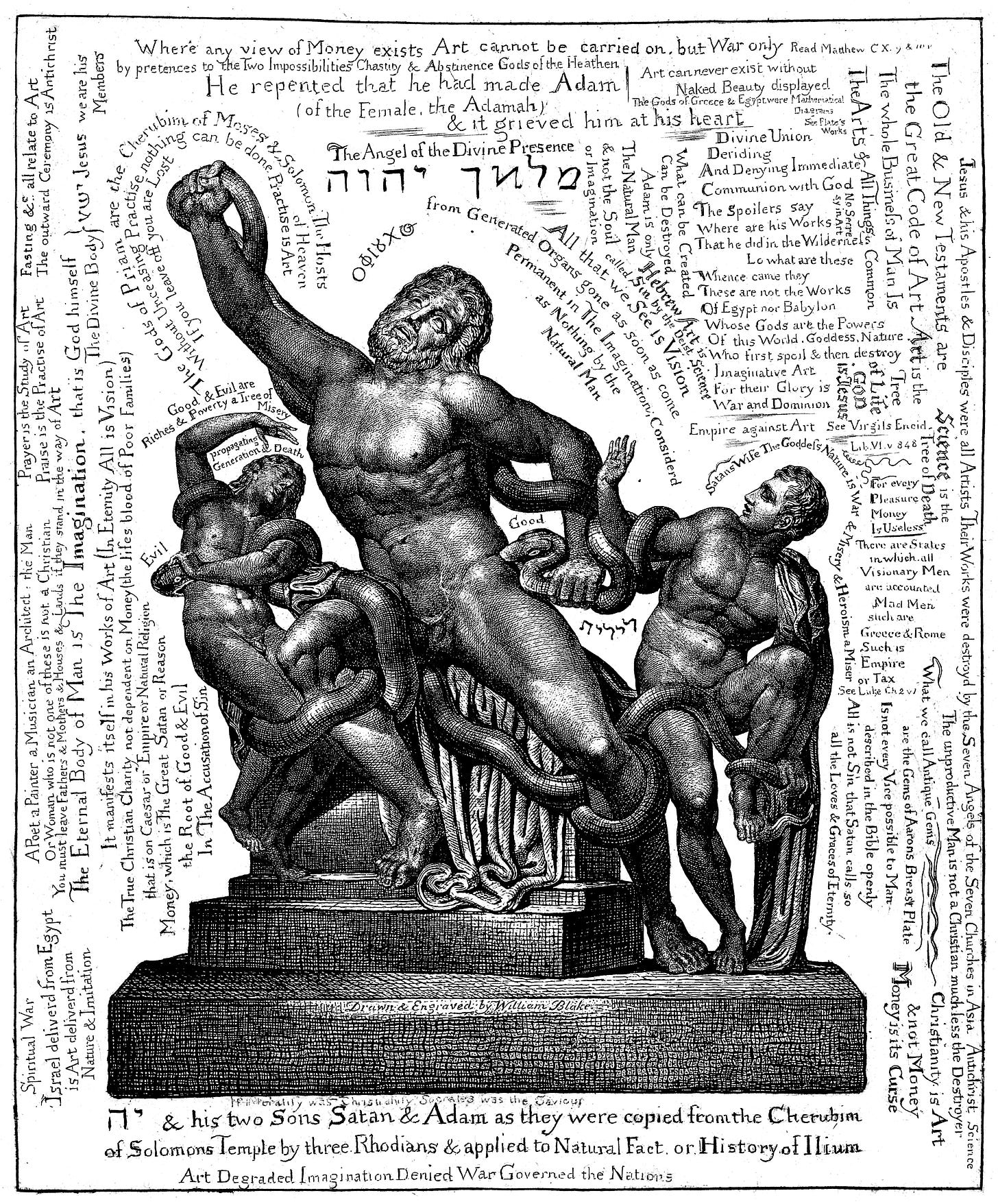

The symbol killeth

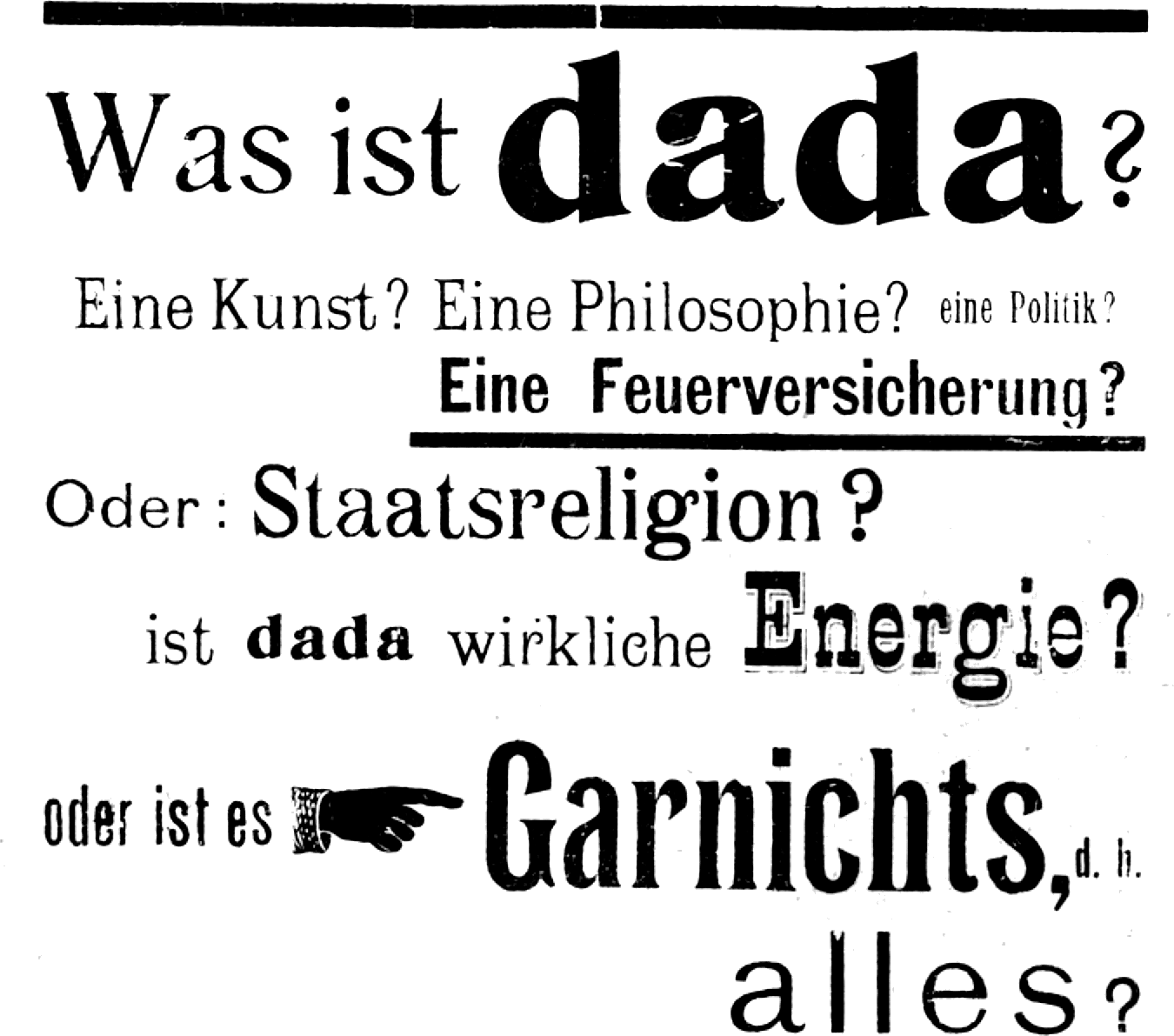

Polysemia against spoken power

Blake’s chaos

The Book of Job is the Song of Songs of scepticism, and in it terrifying serpents hiss their eternal question: Why?

Heinrich Heine

... behold the throne

Of Chaos, and his dark pavilion spread

Wide on the wasteful Deep

Milton

Last year, I interviewed Jason Wright, whose Blake's Job: Adventures in Becoming, uses Blake’s ideas about the biblical character of Job in his Illustrations to the Book of Job to describe the author’s experience leading psychotherapy workshops for recovering addicts. It is nice to see Blake put to such use, and I recommend the book. It has been warmly reviewed by other Blakeans.

As Wright has it, "we perpetually face a death, a death of a self, for a new sense of self to emerge in its place, born into and from the context, we inhabit."1 It is true that Blake’s Job cycle can help model that process of rebirth. Still, the essence of the Job myth concerns more than the cycle of death and rebirth which is the road of becoming.

This process of rebirth is no doubt part of what Blake is saying – it has clearly helped Wright enormously to focus on it in his therapeutic practice – but it is far from the whole story. If nothing else, such an interpretation skirts the core questions in Job about the meaning of suffering generally, and the nature of grace and providence.

Personal development and the overcoming of trauma involve coming to terms with suffering, but the existence of suffering on the scale of the Shoah, the Nakba, the Great Leap Forward, slavery in the Americas or the Soviet Gulag, demands a context broader than that of the wellbeing of the survivors, as important as that is. Whether or not the survivors ever come to terms with what happened to them, we must ask what God was thinking of in allowing it to happen.

The addict may have as a great resource the power of their mind to overcome its own clinging to death and choose life in the face of all the odds. The addict arguably even has a responsibility to themselves to overcome their suffering this way to live. Whatever circumstances led to their addiction, and however much others can support them, the addict can only really put their addiction behind them once they have accepted their own frailty and weakness.

We can’t say the same about the victims of the Holocaust, of colonialism and slavery, or of the Russian mass transports and the collectivisation of agriculture. Understanding suffering on such a scale requires more than therapy and personal transformation. It calls for politics; but before that it calls for wisdom and theology.

Wright sees Job through Blake’s eyes, but he understands Blake in turn through the mirror of Jung, through Jung’s followers (principally Hillman and Erdinger), and through esotericism generally.2 It seems to make sense to respond to the questions Jason’s book raised for me by turning this around and viewing Blake instead through the eyes of Job, which I try to do below.

Patient Job, militant Job

The figure of Job is widely recognised in the West, though most people are only dimly aware of his real story and its resonance. A quick poll of my friends, and visiting some randomly chosen websites, shows that Job is mostly remembered for having been hard done by – losing his wealth, his family, and his health – but also for sitting it out patiently until God does the right thing and restores his fortune. Job’s stoicism is summarised in the Gospel of James: “Behold, we count them happy which endure. Ye have heard of the patience of Job, and have seen the end of the Lord; that the Lord is very pitiful, and of tender mercy” [James 5:11].3 This is the character that biblical scholars call the ‘patient Job’.4

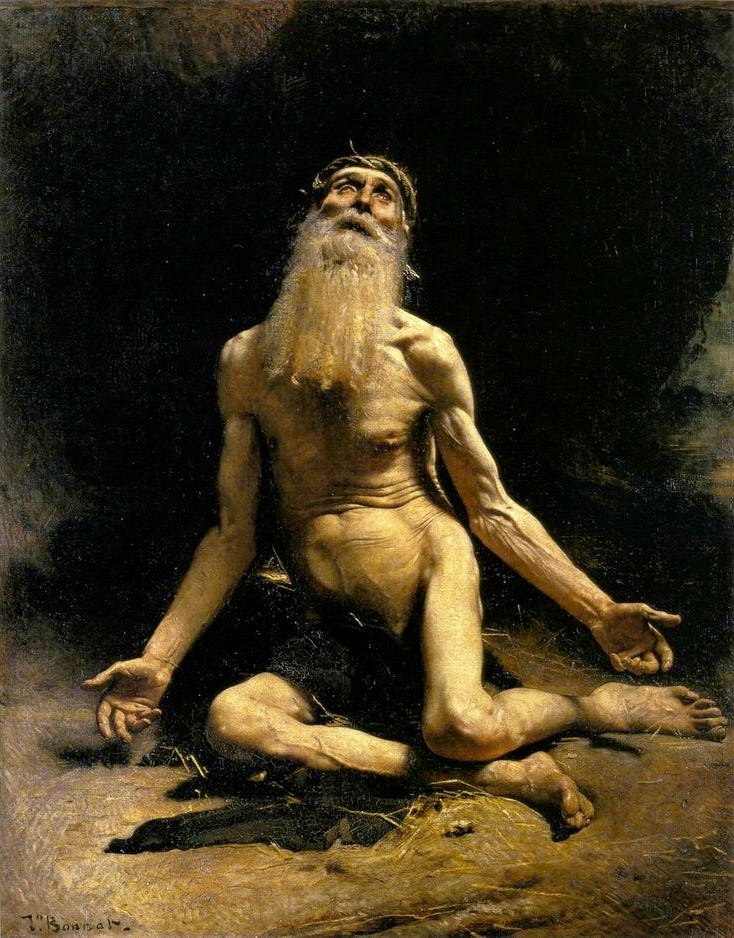

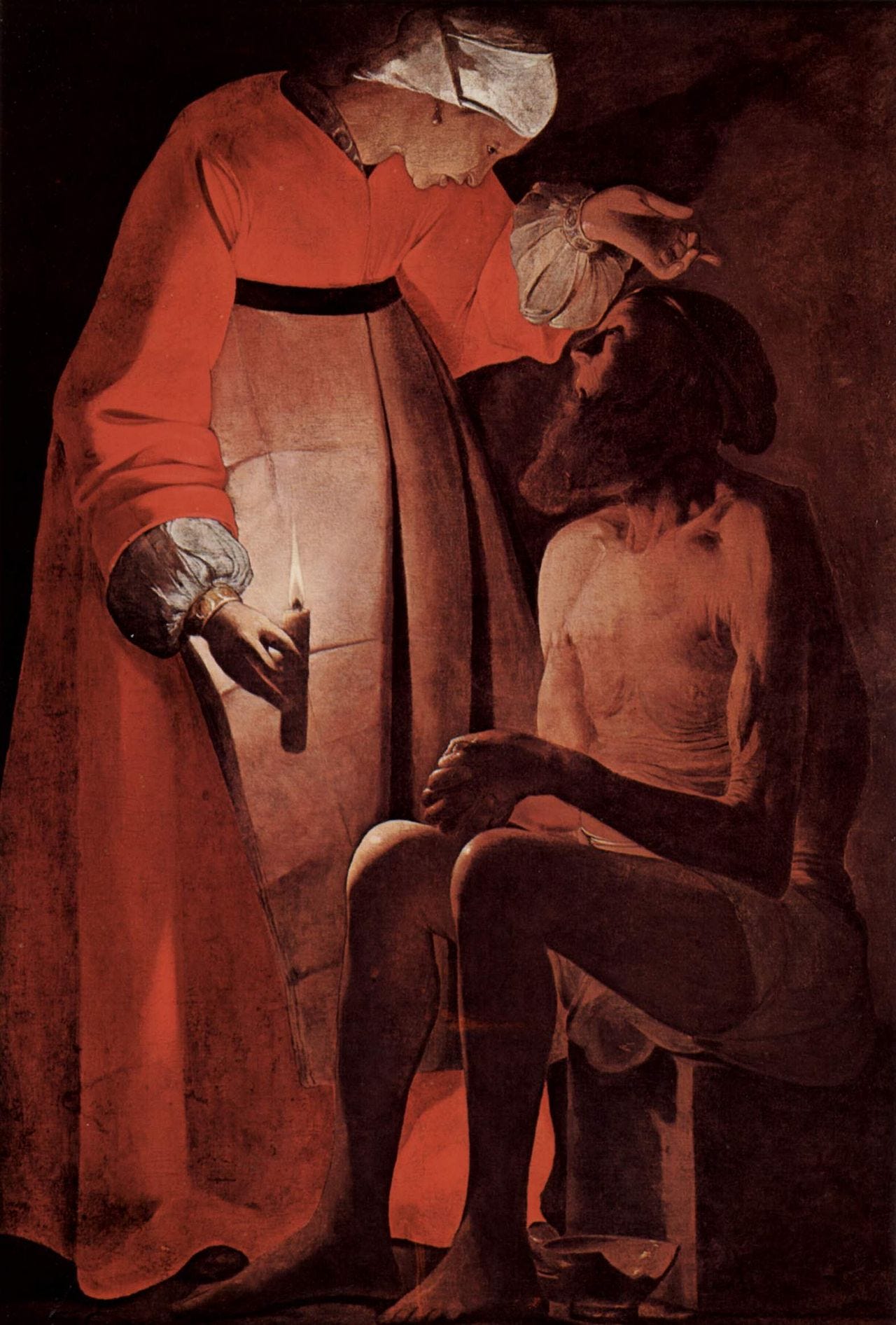

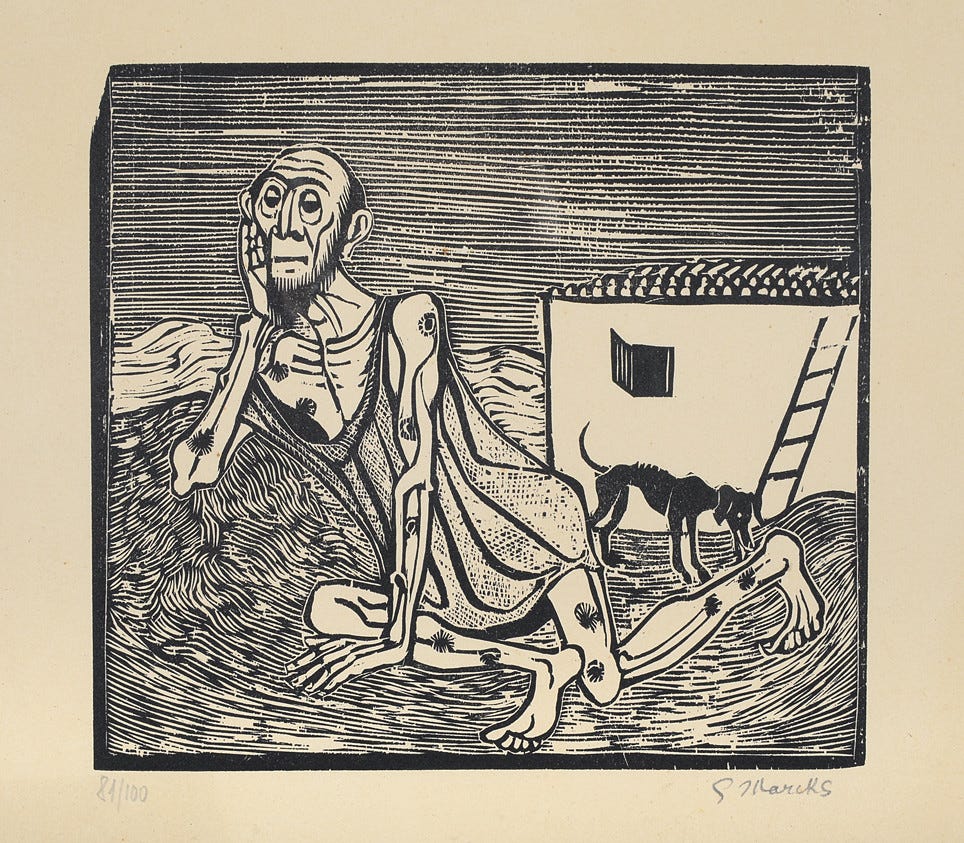

Some remember Job’s long-winded and ineffectual friends – Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar and Elihu (though none by name); some recall the image of Job sitting on a dungheap scraping at his sores and boils with a handy potsherd (“And he took him a potsherd to scrape himself withal; and he sat down among the ashes.“ [Job 2:8]); some even know that the burial service today still quotes Job (“the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” [Job 17:14]) In short, people have mostly heard of the ‘patience of Job’ and can recall some of the more colourful details of his story.

Entering the mind palace of theodicy

How many modern readers recognise the original story of Job as among the world’s great works of literature and imagination, woven from the Job poet’s concrete lyricism, from folk wisdom, theological speculation and ancient Hebrew liturgy?

How many recognise that the story is saturated with echoes of Canaanite creation myths that embody its unconscious appeal?

How many readers of Blake realise that the story he is illustrating is radically at odds with the bulk of the Old Testament stylistically, morally, and especially in its view of a supreme deity with little interest in the doings of mankind – in sharp contrast to the covenantal Yahweh of the Books of Moses?5

How many see that the Book of Job’s innocent-sounding opening words (“There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job; and that man was perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil.” [Job 1:1]) are a gatehouse to what is arguably the great mind-palace of Western moral, theological and existential speculation?

As a man profoundly in awe of the Bible, and as one of its most devoted students –someone for whom, as for so many English dissenters, the Bible was his ‘paper Pope’ – William Blake addressed Job’s story repeatedly, creating a body of paintings and engravings so appealing to the popular imagination that, as one Job scholar puts it, “Blake has come to own Job the way Michelangelo owns the creation of man and Leonardo the Last Supper.”6

Blake scholar, Bo Lindberg, argues that it should be possible to read Blake’s Illustrations without any context other than whatever knowledge an ‘educated’ contemporary would have brought to the task of looking at them, saying that if this were not the case the work would be an artistic failure: “the understanding of Blake's Job should not rely on background references: the plates should tell a story that can be read without the aid of any external system of reference such as the mythology of Blake’s writings, theological literature or traditional iconography. And this story must be a complete story, bearing a mind that a complete story is not necessarily the same thing as the complete story.” He is essentially right.7

The story we would extract in this way would be the first-order meaning of the work, as it was intended to be understood by Blake. It does not exclude the possibility of other meanings attached to the work, deliberate and unintentional / unconscious, by Blake or by others. We will therefore want to round out the impression formed by our ‘educated observer’ by also considering Blake’s myths and philosophy more generally, based on what we know of them from studying works other than the Job Illustrations and applying this to our interpretation. This allows us to tease out further layers of meaning and correspondences. Blake scholars have provided several such overlapping and competing accounts.8

To account for everything Blake built into his work, consciously and otherwise, means digging deep into the Bible, Job legend and commentary, and Blake’s mythology alike. The point is that the first level of such interpretation, the one Blake aimed at his basic readership, does not require such depth, although it perhaps does require some extra background information these days to account for the change in the general culture of ‘educated viewers’ between Blake’s time and ours. Arguably Blake’s viewers then came equipped with a greater understanding of Job’s story, but even then, eg., the texts added to the engraved images exist to prompt the viewer, whoever they may be and however much knowledge they may have of Job.

The Job tradition

Engaging fully with Blake’s images requires understanding the story of Job and its reception – a story of some complexity given the great depth of its history, the range of people who’ve commented on it, and the wide dissemination of the story in art and popular culture. Such an understanding is weak in many accounts of the Illustrations.9

Knowledge of ‘the man from Uz’ and how his story was recorded and disputed is necessary because it highlights Blake’s argument by showing us where Blake departed from tradition to speak for himself, and the many cases in which he did not. Missing this context blinds us to what is specific to Blake’s reading of Job versus what is common to tradition. Better acquaintance with Biblical and scholarly analysis of the Book of Job can also correct individual misreadings of both Blake and Job based, eg., on outdated translations and interpretations of the Bible text.

The Job tradition that sets the scene for Blake’s vision is considerably more complicated than the image of the meek and patient Job implies, which means that conflicting interpretations of Job’s story are as important to understanding Blake as the popular tale of Job’s suffering and redemption. We need to understand something of the entire field of interpretation, even if only in broad terms, to see what paths Blake himself took through this meta-story.

To clarify Blake’s take on the story of Job, and the story of Job as it exists independently of Blake, I talk here about the following topics:

An overview of the issues in interpreting the Book of Job, and how it has been interpreted historically. Some of this is introduced in the course of telling the story of Blake’s Job, while some is presented separately.

Some of the history of Blake’s Job project

An account of Blake’s version of the story image by image

How Blake’s work is distorted by treating it as a cypher for other traditions (Traditionalism, Neoplatonism, Jung)

I suggest a reading of one aspect of the story – the significance of the foregrounding by Blake of the mythical beasts, Behemoth and Leviathan – which suggests an insight on Blake’s part impacting not only his understanding of Job’s revelation but also his own ideas of truth and divine vision.

Some see heaven, some see hell

Blake referred to Job throughout his adult life, presumably because he thought his story significant. However, Blake’s understanding focused on Job’s personal transformation, which is not a major theme in the original telling. For Blake, Job’s story is that of a man who transcends his misery by changing how he sees God.

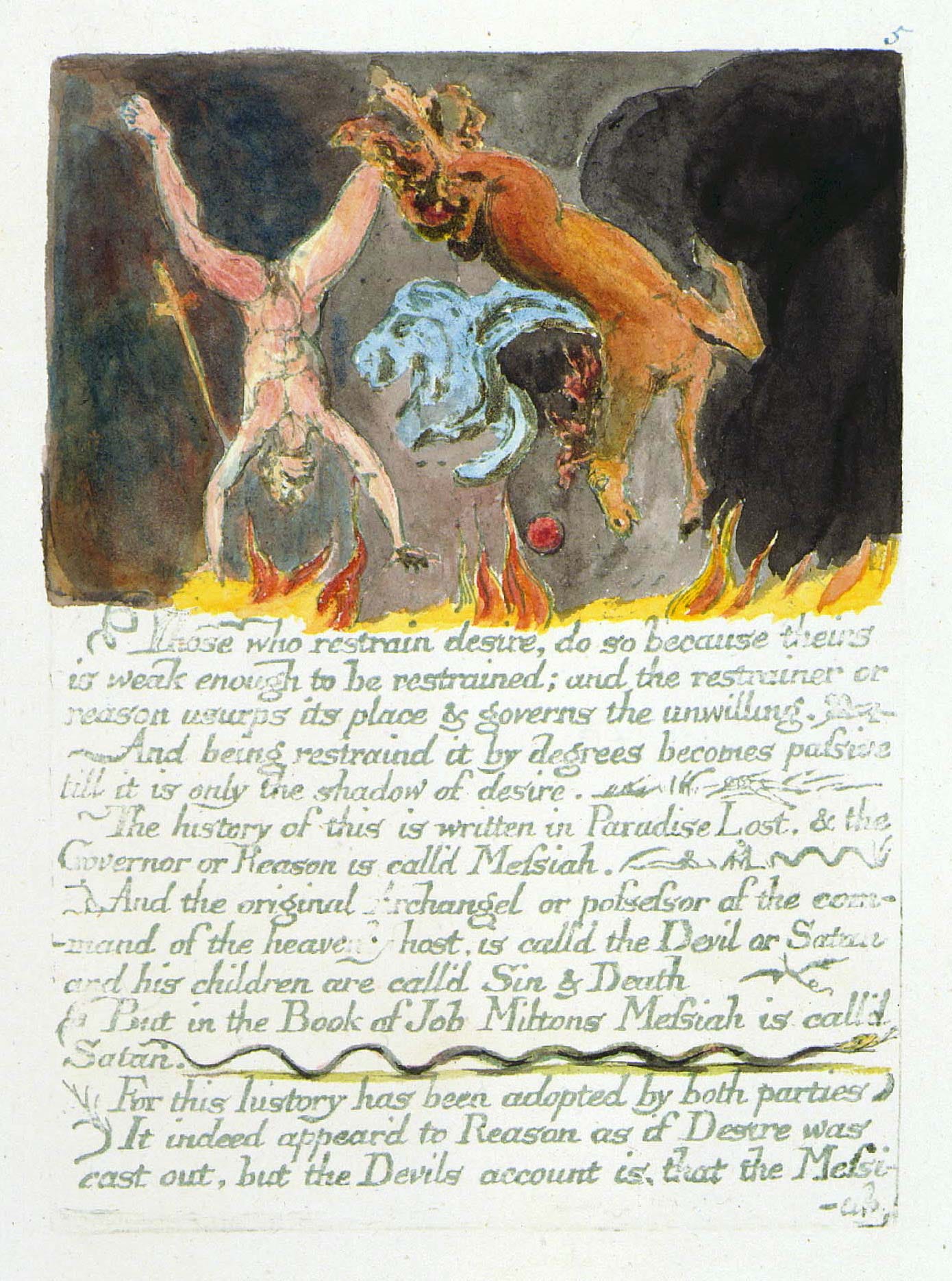

That Blake had original ideas about this transformation in Job is obvious as early as 1790, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, where he says:

Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained; and the restrainer or reason usurps its place & governs the unwilling… The history of this is written in Paradise Lost. & the Governor or Reason is call'd Messiah. And the original Archangel or possessor of the command of the heavenly host, is calld the Devil or Satan and his children are call'd Sin & Death. But in the Book of Job Milton’s Messiah is call'd Satan. For this history has been adopted by both parties. It indeed appear'd to Reason as if Desire was cast out. but the Devils account is, that the Messiah fell. & formed a heaven of what he stole from the Abyss. This is shewn in the Gospel, where he prays to the Father to send the comforter or Desire that Reason may have Ideas to build on, the Jehovah of the Bible being no other than he, who dwells in flaming fire.10

William Blake

He’s saying that Milton’s Paradise Lost tells the story of the cosmic struggle between ‘reason’ and ‘energy’, but that Milton wrongly assigned the divine, angelic role to reason and the evil, demonic role to energy. Blake believed that the Book of Job showed those roles in their correct, reversed order: in the Book of Job, the demonic role is played by reason, and the divine role by ‘spirit’. Hence the Book of Job becomes for Blake a corrective to the deistic theology of his time.

Flipping Milton

This reversal is arguably the most vital part of Blake’s vision. Blake ‘flips’ Milton (to borrow Jeffrey Kripal’s coinage) (“this history has been adopted by both parties”), with the result that angels and demons, Satan and Yahweh, swap places and intermingle as the perspective shifts. This move has proved both scandalous to many, and yet very attractive to some modern readers.

More accurately, Blake thinks Milton has flipped Job, so Job is simply being put back in the right place by flipping Milton in turn. Blake sees the Book of Job as expressing the real state of affairs (divine spirit, demonic reason), thus emphasising the importance of Job’s story to Blake’s vision.

Plate five of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell – which contains most of the text above about flipping Milton – shows a horse and its rider upended in mid-air (the rider’s upturned sword now becomes a crucifix), much as Blake thought Milton upended Job. Blake wants to upset Milton’s upending and put the story straight.

Note especially – a key to understanding Blake’s Illustrations as a whole – that this retelling involves the assertion that the Jehova of the Old Testament, the God of the Book of Job, when he manifests as reason and law, is “no other than he, who dwells in flaming fire”, ie., Satan. As we’ve noted, for Blake, Jehovah, among other things, is, or can be, Satan.

For Blake, the story of Job is the story of Albion. Both begin in peace, but in some sense divided against themselves. Both are tested by Satan, and both fall. But both rise again. Job sees God, casts off Satan, and is restored to life and prosperity, while Albion reintegrates and inaugurates the New Jerusalem.

The easiest way to approach our account of Blake’s Illustrations is by telling the original story, then relating Blake’s images to it while mentioning historical disputes over its interpretation along the way. I’ll begin with an outline of the Old Testament story.

Perfect and upright

The story of Job is contained in the prose prologue and epilogue of the biblical Book of Job (chapters one and two, and then the final chapter, forty-two). For a long time, the Book of Job was considered the oldest book in the Old Testament, written in Egypt before God gave the law to Moses. For that reason, Job was considered the last of the patriarchs.11 Origen “says that Moses… translated the book of Job from the Syriac, read it to the Israelites in Egypt, and said, “you shall be delivered as Job was.””12

In the prologue we learn that Job is a man of good character (“perfect and upright… one that feared God, and eschewed evil” [Job 1.1]. He is wealthy, a proud father, a generous employer, a good citizen and a friend to the needy: basically, he’s holding a full house in terms of conventional piety and ambition. In biblical terms, he’s a winner.

Job is not an Israelite. The name ‘Job’ or its cognates has been found in archaeological inscriptions across the region around Canaan, dating from around 2000 BCE onwards.13

Job lived in ‘the land of Uz’, thought by scholars to be trans-Jordanian, either to the north or south, possibly in the south-east of the region of Edom. Nevertheless, he worships Yahweh (as the people of Edom were said to have done, before the Israelites), albeit that he calls him by an impressive array of names, including El, Eloah, Elohim, Shaddai, Adonai (‘Lord’), Yahweh, Kabir (‘Mighty’), Asah and Paal (‘Maker’).14 His era is that of the patriarchs, in the mid-second millennium BCE.15 Job also appears in Islamic traditions, including in the Quran itself, as Ayyub (Ayūb), with a similar reputation. The haziness concerning Job’s exact time and place suggests an author who’d like us to think of Job as having lived “a long time ago, in a place far away.”16

Sabean and Chaldean raiders seize Job’s flocks and massacre his servants

Plotting with the Sons of God

Having introduced Job, the story gets underway when Yahweh is holding court in heaven one day with his retinue, the ‘Sons of God’ (bene ha Elohim), among whom is his enforcer and cosmic chief of police, Satan (‘ha Satan’: ‘the Adversary’, ‘the Accuser’.)17 Satan and Yahweh get to discussing Job, “Hast thou considered my servant Job?”18 Yahweh praises him as an especially righteous and devout follower. Satan, ever alert to the faintest fluttering of potential treason, counters that, on the contrary, he thought Job would probably curse and betray Yahweh rather than worship him if his wealth and family were taken away. He thinks Job only worships Yahweh because Yahweh has pampered him. Yahweh, rattled, allows Satan to test Job.

Immediately, Sabean and Chaldean raiders seize Job’s flocks and massacre his servants; the ’fire of God’ falls on the rest of his possessions and destroys them [Job 1:16]; finally, a whirlwind causes a building to collapse on his children as they share a meal: they are all killed. Job loses everything.

Rather than curse God, Job continues to praise him, uttering words that are still part of the burial service today: “the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord” [Job 1:21].

Satan remains anxious and unconvinced by Job’s continued outward loyalty. He continues to press Yahweh, saying that if only he were allowed to “touch his bone and his flesh”, Job could be made by Satan to reveal his underlying faithlessness and curse his maker. Satan believes Job is weak and should be more strenuously tested. Yahweh, while insisting that Job should not be killed in the experiment, allows Satan to further afflict Job with an agonising disease that progressively eats his flesh.

Curse God and be done with it

Job is reduced to sitting on the town dungheap, rancid and filthy, scraping at his sores. His wife seems to say that he may as well curse God and be done with it, as Yahweh looks set to kill him anyway. But Job persists. Three friends arrive (Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar – the ‘comforters’) to sit with Job for seven days. They do not recognise him at first as his disease has so disfigured Job and he is in such despair. They sit silently.

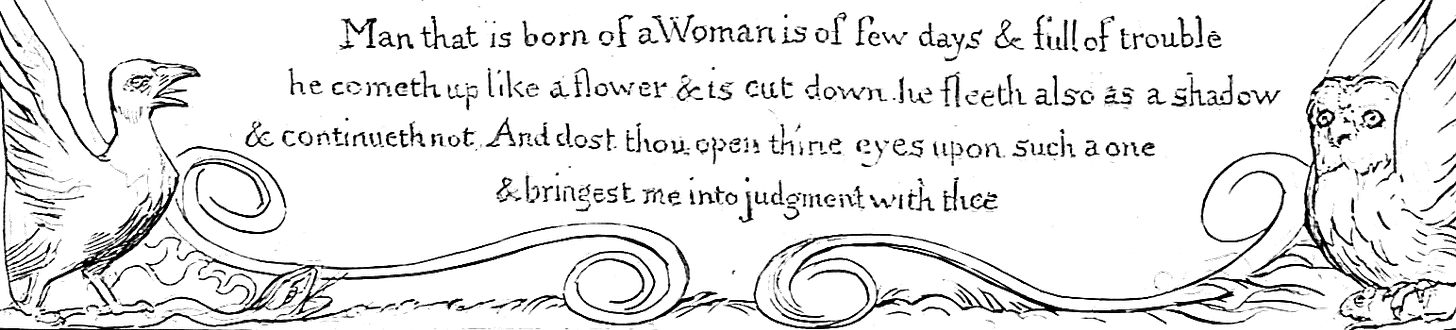

There ends the prologue of chapters One and Two of the Book of Job. In the next thirty-nine chapters, Job launches a passionate outcry against his own existence, in a poem which stands among the most thrilling of the Old Testament, with “a virtuosity that transcends all other Biblical poetry”.19 It begins:

Let the day perish wherein I was born, and the night in which it was said, There is a man child conceived.

Let that day be darkness; let not God regard it from above, neither let the light shine upon it.

Let darkness and the shadow of death stain it; let a cloud dwell upon it; let the blackness of the day terrify it [Job 3:2-5].

The comforters speak several times each and are replied to in turn by Job as they pontificate about what he could have done to invite such dreadful retribution; a conventional Hymn to Wisdom (Hokmah) is sung which cannot be attributed meaningfully to any of the story’s characters since its attitude suits none of them; a younger man, Elihu, butts in to offer a different take on Job’s moral standing; finally, Yahweh himself speaks, challenging Job directly in a poem that rivals Job’s own earlier hymn to annihilation in the simple power of its imagery.

These intermediary chapters, inserted by the compiler of the Book of Job between prologue and epilogue, provide the meat for centuries of raging historical, inter-faith, and secular debates about the theological and ethical meaning of Job’s trials, about theology and theodicy.

Out of the whirlwind

Robert Alter notes the “palpable discrepancy between the simple folktale world of the frame-story and the poetic heart of the book.”20 There are reasons to think that the frame story is merely a pretext for the author to insert the theological debates it bookends:

when the LORD speaks from the whirlwind at the end, He makes no reference whatever either to the wager with the Adversary or to any celestial meeting of 'the sons of God,' a notion of a council of the gods that ultimately goes back to Canaanite mythology. The old folktale, then, about the suffering of the righteous Job is merely a pretext, a narrative excuse, and a pre-text, a way of introducing the text proper, and what happens in it provides little help for thinking through the problem of theodicy.21

When the folk tale picks up again in the epilogue, as mentioned, God speaks to Job “out of the whirlwind”,22 and Job undergoes a transformation as a result of this experience (“I have heard of thee by the hearing of the ear: but now mine eye seeth thee,”) after which he keels over and submits, “in dust and ashes” [Job 42:5].

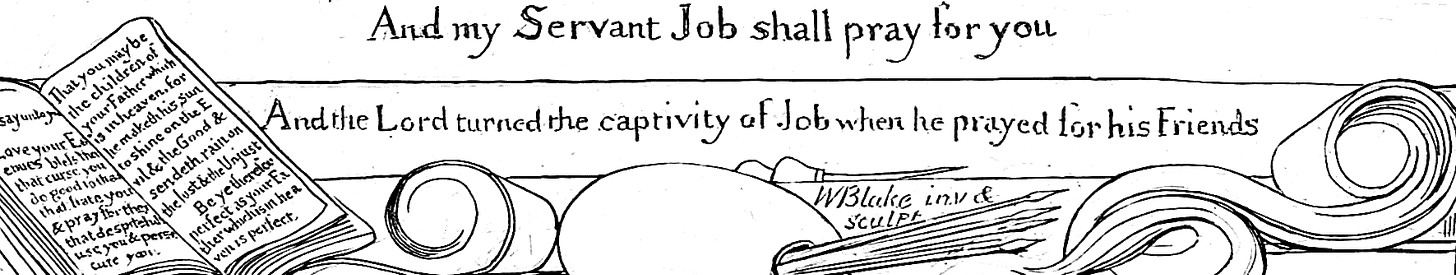

In a key section of the epilogue, Yahweh calls out the comforters, saying, “ye have not spoken of me the thing that is right” [Job 42:7]. He tells them to present sacrifices to Job, who is to intercede on their behalf with Yahweh to ask for his forgiveness for them. We’ll see later the sense in which they had not spoken of Yahweh “the thing that is right.”

Job’s latter end

As for Job himself, his fortunes and his children are restored: Yahweh “blessed the latter end of Job more than his beginning” [Job 42:12]. Job went on to live to the age of a hundred and forty. His family prospered; his daughters were married off with great dowries. In the end, Job “died, being old and full of days” [Job 42:17].

Moralists love the bit of the story where Job gets a payoff for his endurance.

The prologue and epilogue together most likely recount an old Canaanite folk tale, with material newly written or inserted from other sources (Israelite liturgy, wisdom literature, Psalms) to pose theological questions and leaven the drama of the basic telling. This is the story Blake illustrated, albeit that he turned it into a vehicle for his own ideas about the nature of the compact between Yahweh and Satan. In turning Job’s story to his purposes Blake was no different to other commentators from the time of the poet of Job down to our own. What did he make of the story?

Blake’s use of Job

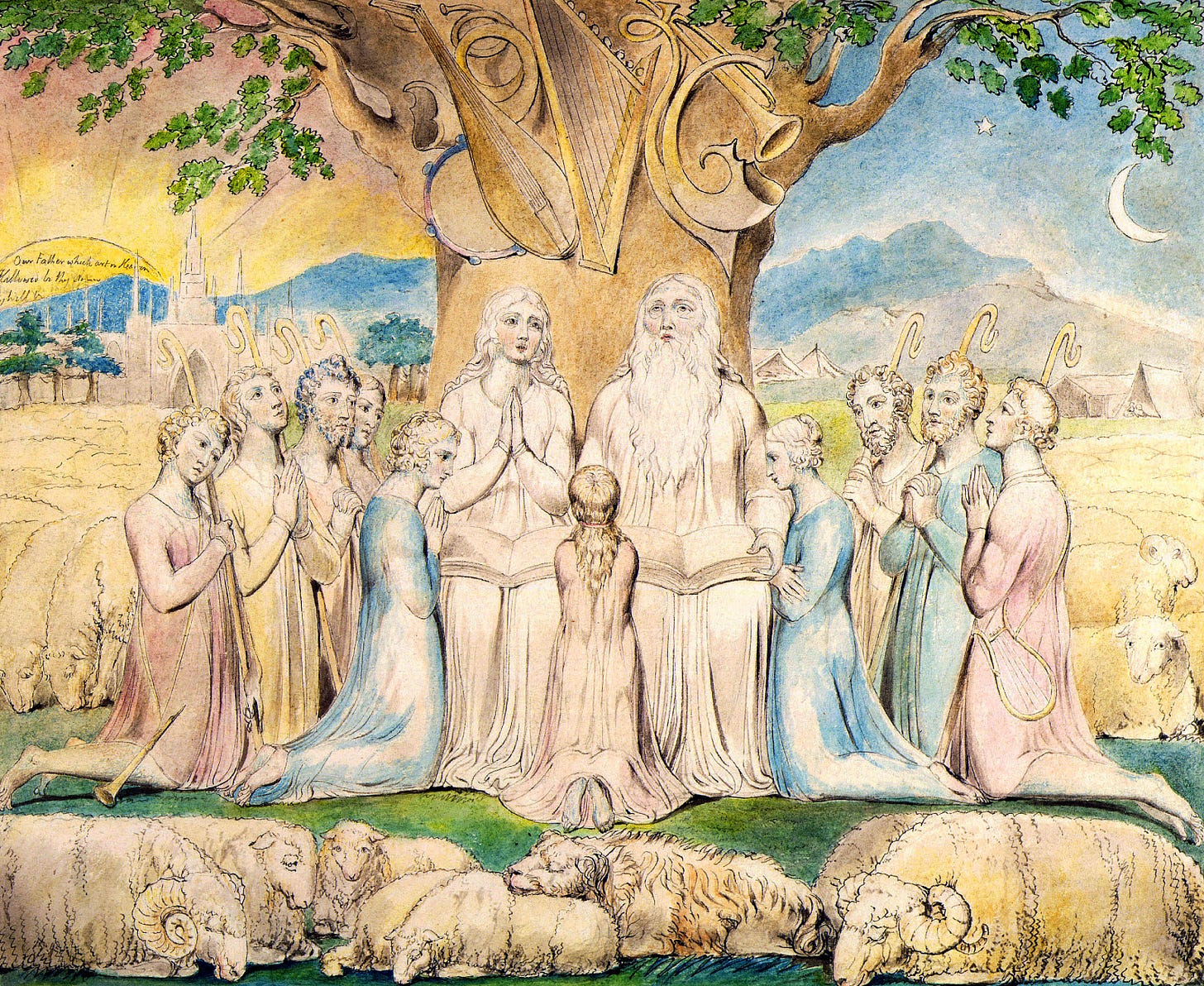

Blake dealt with aspects of Job’s drama at various points without telling the story as a whole or presenting any conclusions about it. His earliest depiction of Job is possibly the watercolour, Job and his Family, which Lindberg dates as early as 1784, though this is disputed.23

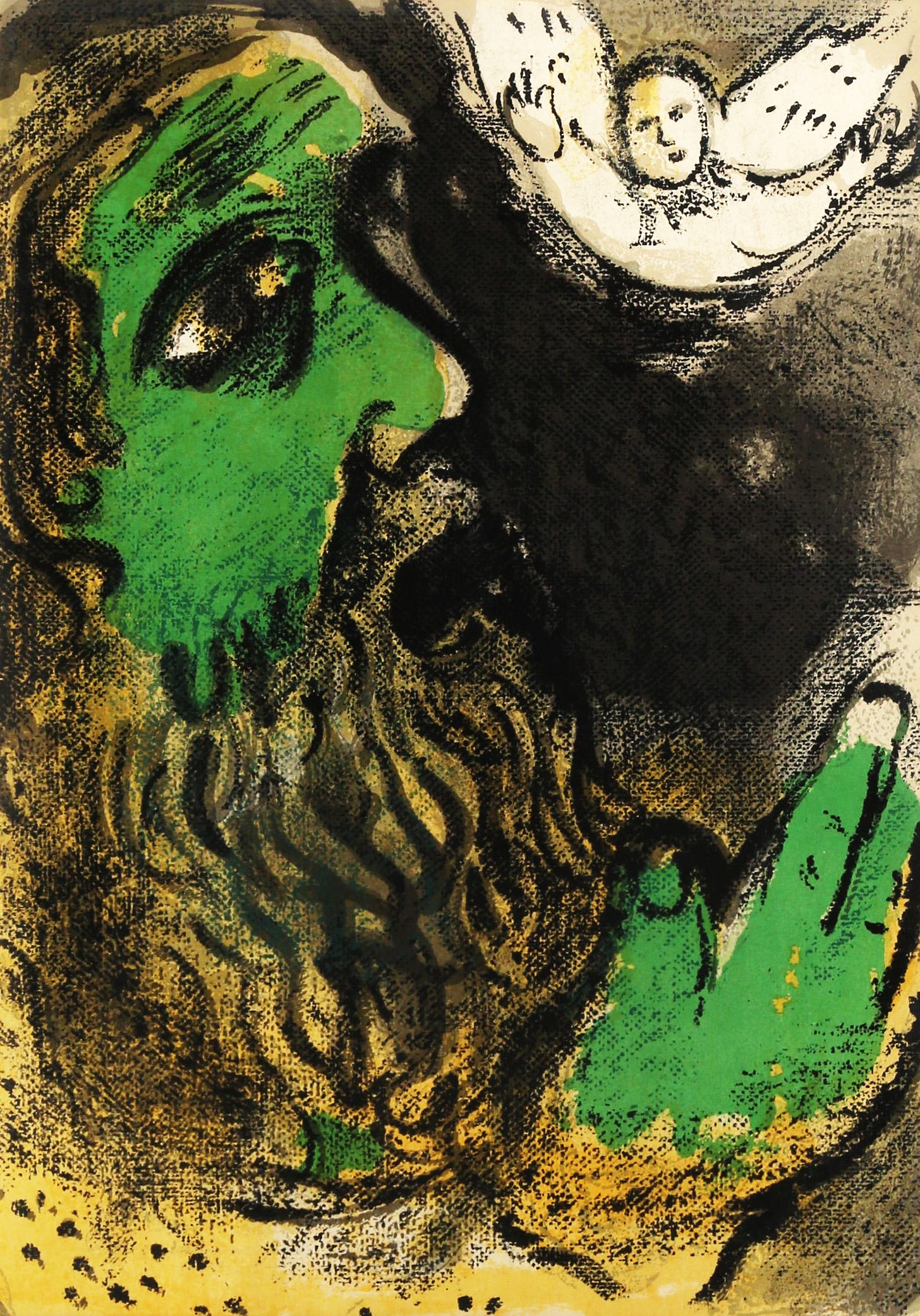

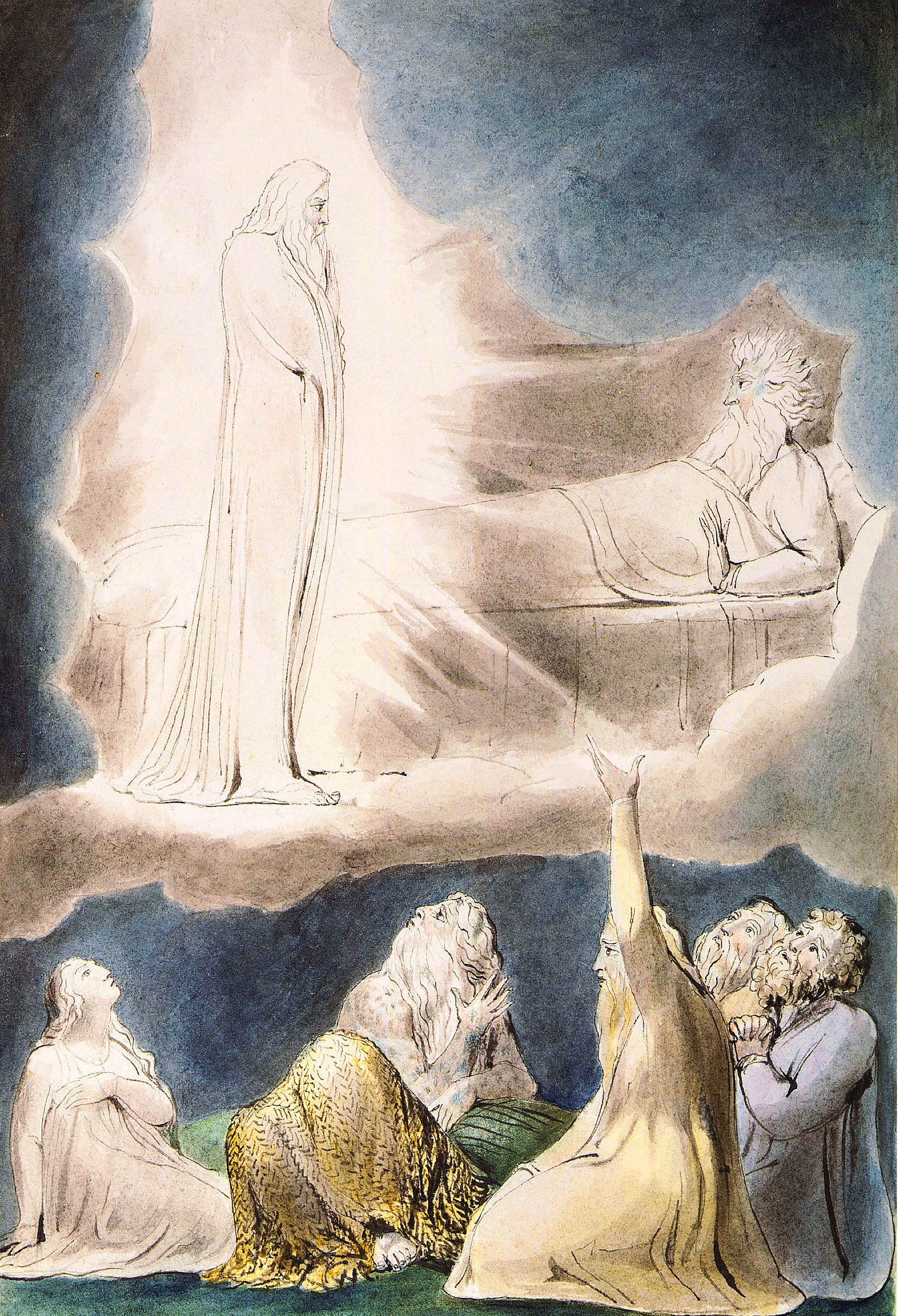

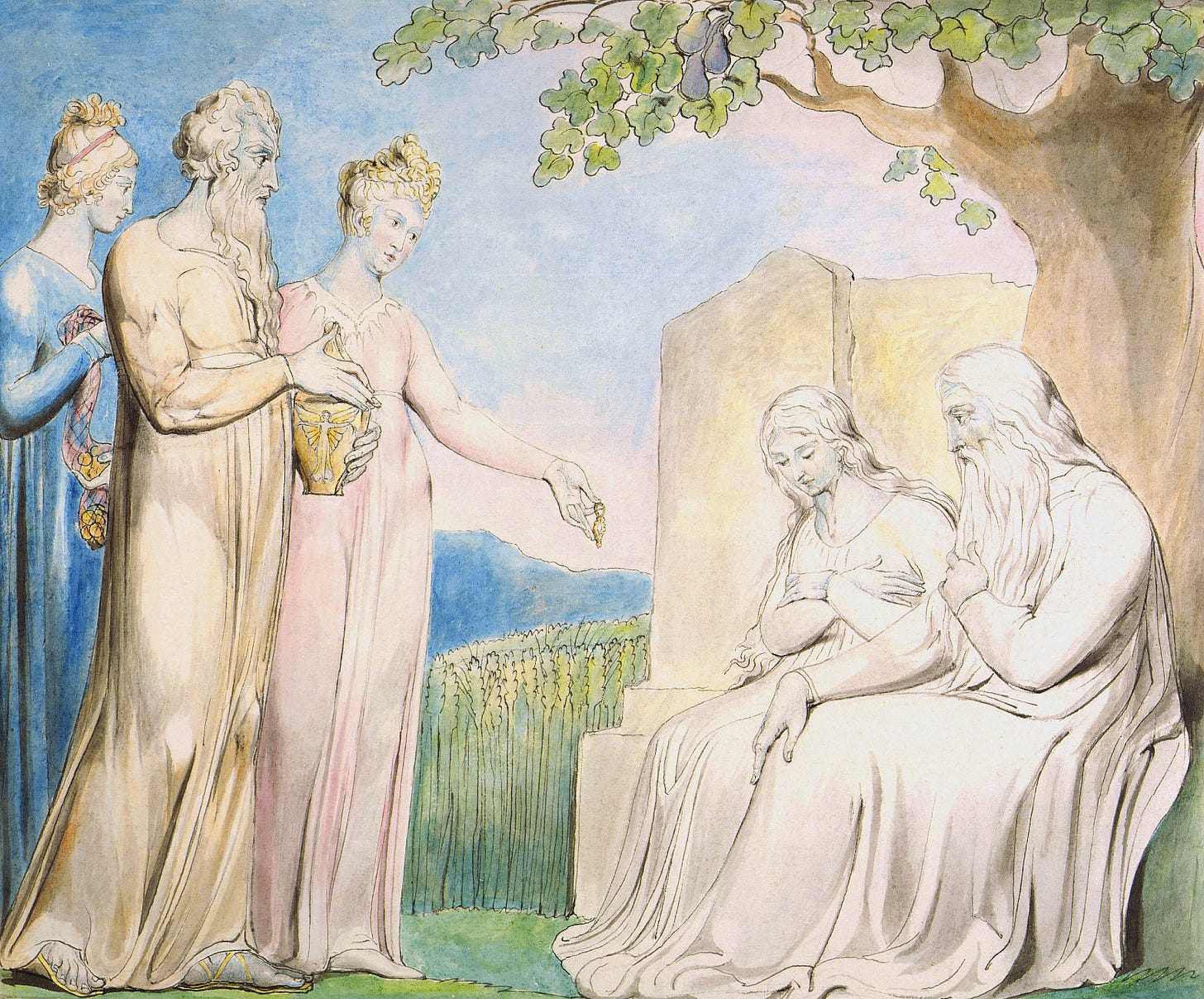

Blake’s engraving of Job, his wife and the comforters (Job, 1793), and the painting of Yahweh speaking from out of the whirlwind (Job Confesses His Presumption to God Who Answers From the Whirlwind, 1803-5), are pictured above. To these can be added Job and His Daughters (1799-1800), part of a series of tempura and ink images on themes from the Bible, probably commissioned by Blake’s patron, Thomas Butts (which was eventually incorporated into the Job series when Blake was preparing the Linnell watercolours).

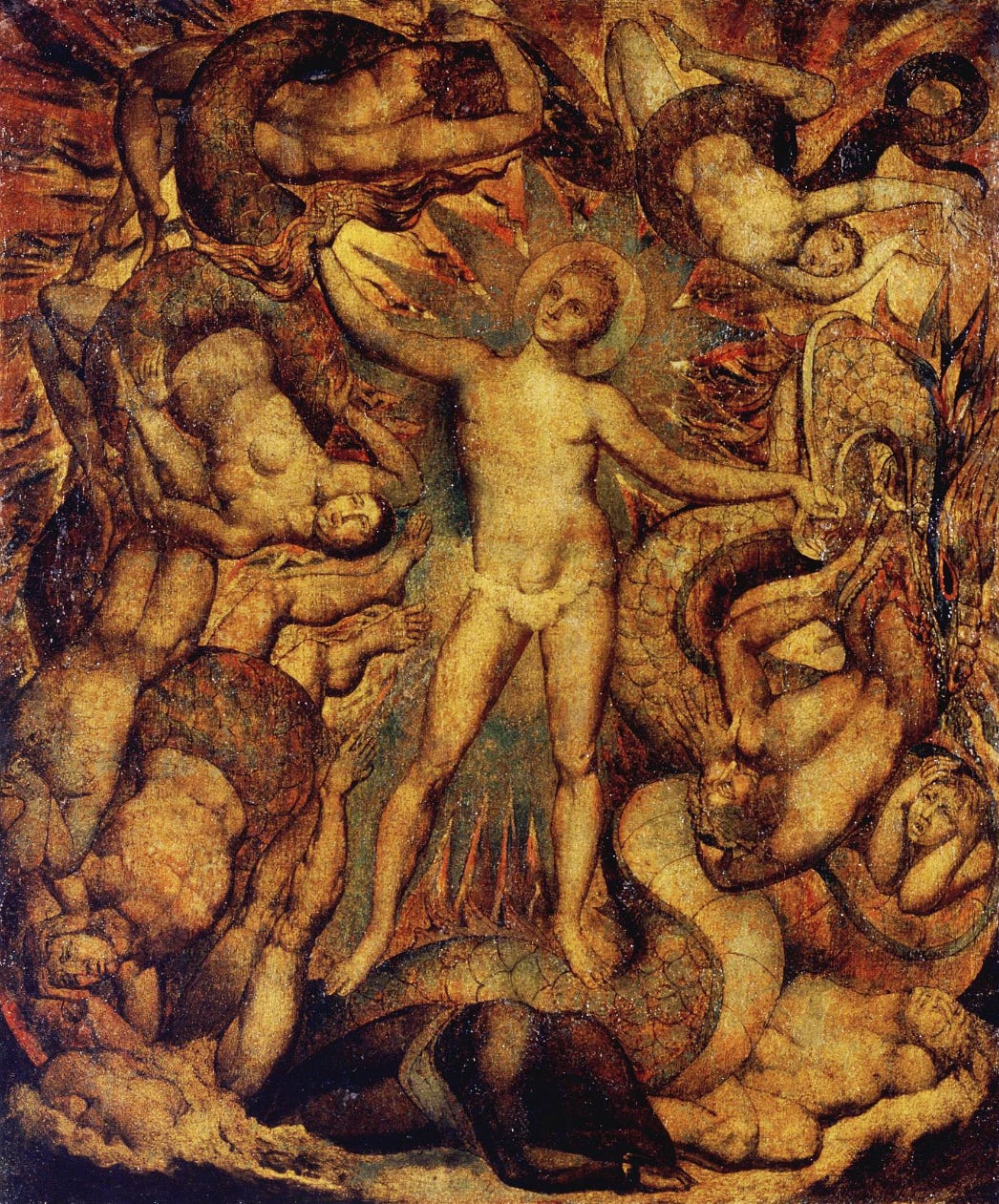

As well as illustrating the Job story as such, Blake used its themes independently of it: for example, in The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth (1805) and The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan (1805-1806), the characters of Leviathan and Behemoth play a central role in the political allegory, and they derive from Yahweh’s speech in [Job 40-41]. Thus the elements of the Job story, which themselves come from an older layer. ofmyth, are put to work independently by Blake.

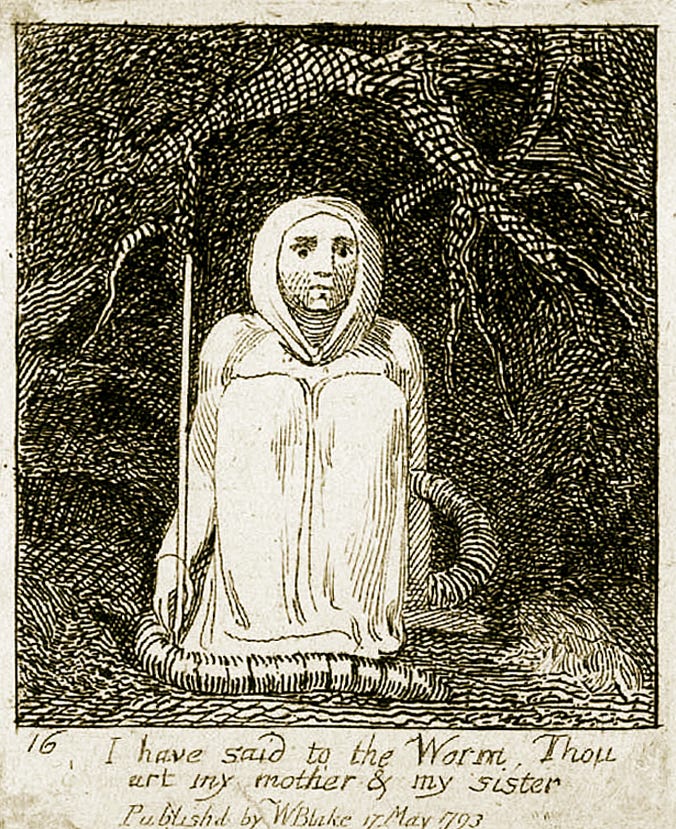

Blake refers to Job in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), when he turns Milton’s hierarchy of reason and energy on its head, as noted above, and also, eg., in the final plate of his series, For Children: The Gates of Paradise, where he depicts the spiritual traveller, staff in hand at the end of his journey, seated at the edge of the grave, and he quotes Job: “I have said to the Worm, Thou art my mother & my sister.”24 This reflects Blake’s belief that death and the grave are to be welcomed since they are the gateway to eternal life. He associates this belief with the Job story, and Job’s claim that he will see his ‘redeemer’ in the flesh.

References to Job “occur frequently in Blake's writings”,25 both explicit, where Blake quotes Job to make a point, or implicit, where Blake lends the very structure of the Job story to his own work. In The Four Zoas, Enion echoes Job’s thoughts on the price of wisdom (“But where shall wisdom be found? and where is the place of understanding?” [Job 28:12], and concludes by quoting Job directly; “but it is not so with me.”26

In Milton, Satan accuses Palamabron before the divine council, exactly as happened to Job.27 The entire story arc of Jerusalem, describing Albion’s fall and recovery, is lifted from Job. In the course of the Jerusalem version, Behemoth and Leviathan are mentioned again,28 and Jerusalem quotes a key passage in Job, which Blake (mistakenly) took to reflect the promise of the resurrection of the body: “I know that in my flesh I shall see God.”29

Revenge and the redeemer

Interpreting these lines from the Book of Job as the Old Testament’s promise of bodily resurrection is a staple of Christian thought, but is completely anachronistic, and cannot be made to work at all outside of the typological attitude that sees the events of the Old Testament as prefiguring those of the New Testament and the life of Christ. The passage as a whole reads:

For I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the Earth. And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh I shall see God. [Job 19:25-26]

From Clement of Rome, in the first century CE, through Thomas Aquinas, John Chrysostom and others, this has been interpreted by Christians to mean that the speaker expects to see their redeemer, assumed to be Jesus, “in the flesh”, which it is assumed can only happen once they have been bodily resurrected in heaven, where they will meet Jesus as God.30 In this way, Job gets to anticipate Christ.

This cannot be the meaning of the original text, since the author belonged to a culture that had no such concept of bodily resurrection, or, indeed, of Christ. The solution to the riddle lies with the Hebrew word, go’el, interpreted and translated in most Bibles as meaning ‘redeemer’ (“I know that my Redeemer liveth“).

In fact, in the Bronze Age society that gave rise to the Book of Job, a go’el was someone charged with visiting revenge upon an enemy in the context of a tribal vendetta. If a member of your family was attacked in the course of a feud, a go’el was appointed by the family, charged with exacting revenge. That Job should mention this redeemer at all in the context of a dispute with God is one of the truly remarkable things about the original story:31 Job imagines (out loud) employing a hitman against God.

The business of seeing this ‘redeemer’ / hitman “in the flesh” is simply a way of translating the original thought that, though Job’s body is riddled with worms and canker eating away at it, and Job himself surely hovering somewhere around death’s door, nevertheless he expects to live long enough to witness his redeemer’s revenge go down.

That Blake accepted the standard church explanation of these lines is worth noting, since he is assumed to be always at loggerheads with the Church, and the idea of bodily resurrection was especially important to him. Regarding the resurrection, a key part of his religion, Blake was orthodox.

The business of ‘seeing one’s redeemer’ is crucial to Blake’s wider message in the way he interprets it. For Blake, the Christian promise of resurrection means that our account with God is not closed in this lifetime. We may suffer unjustly, but we cannot complain because our account is finally settled, not in this life but in the next, when God will award or punish us accordingly. Blake accepts the essential moral calculus of the Church once the payment date has been pushed back until after the resurrection: pie in the sky when you die.

When we speak of Blake’s retelling of the Job story we have always to understand that Blake himself, and most of the artists and commentators he drew on, consciously and unconsciously, was not trying to ‘get into the head’ of the Job author or analyse the historical situation he described. The point was never to represent how the ancients interpreted Job’s story, but rather to present that story in the fully Christian sense that could only have emerged after the event, outside of the event itself:

The old illustrators of Job did not interpret the book according to our way of reading it; neither did they try to interpret it according to the meaning it originally held for the Jews. They viewed it in the light of patristic and theological tradition, and stressed its significance for the teachings and liturgy of the church, and for the faith and morals of the congregation (Bo Lindberg).32

Treatment of Job

Blake’s first attempt at a sustained treatment of Job comes with the set of nineteen watercolours created for Thomas Butts, c.1805-06. These follow the drift of the Job story but with some obvious departures to capture Blake’s perspective. In 1821, John Linnell paid for his own version of the Butts set. Butts lent his original set to Linnell to trace, and Blake then coloured the tracings. Blake took the opportunity to create two new images – #17, ‘The Vision of Christ’, and #20, ‘Job and His Daughters’ – in two versions, one for Butts and one for Linnell, thus rounding out the Butts and Linnell sets to twenty-one images each in total.33

Fountain Court

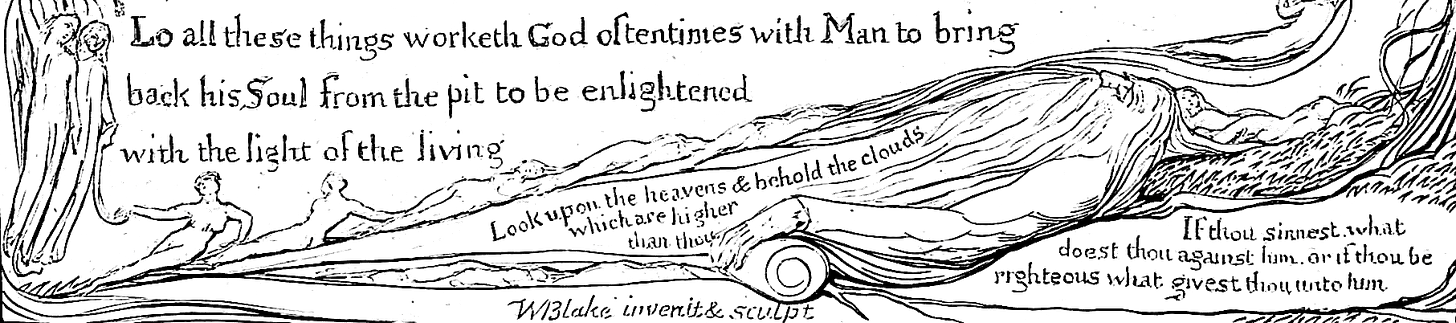

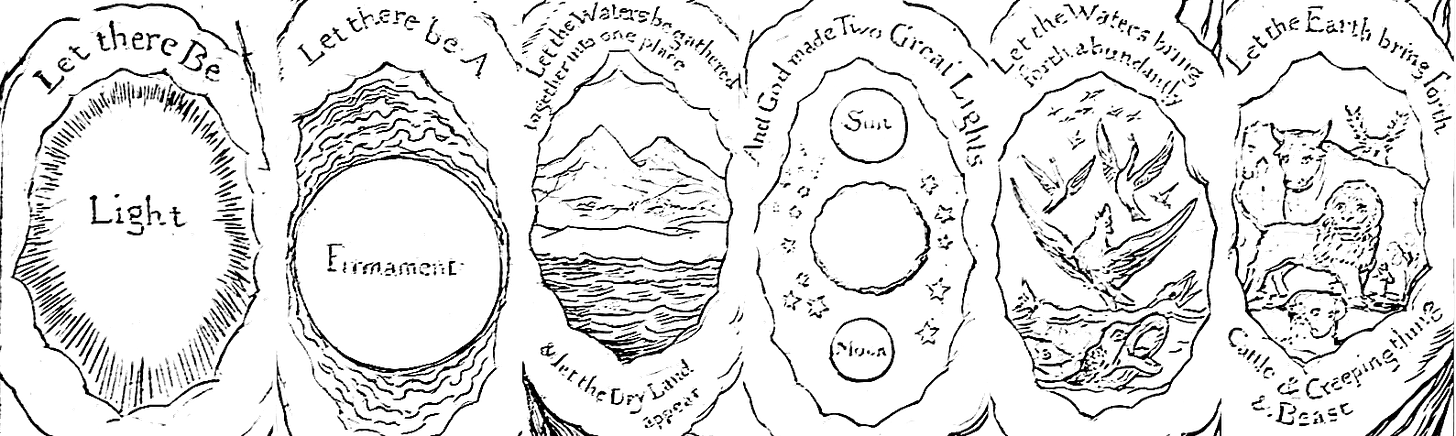

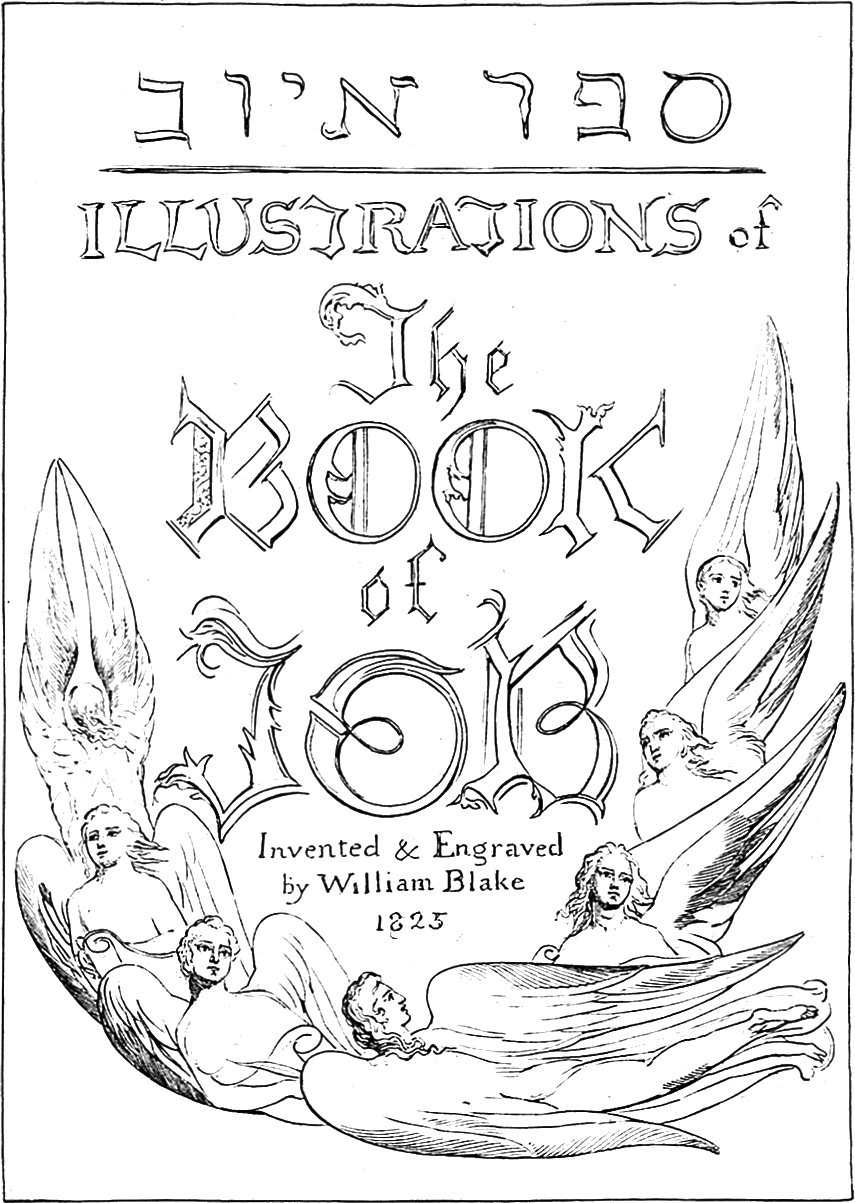

In a bid to raise income for Blake – now living with Catherine in the decrepit Fountain Court off the Strand, and desperate for work – on 25ᵗʰ March 1823 Linnell signed a contract commissioning Blake to turn the Job images into engravings to be printed and sold commercially. Blake engraved all twenty-one images, adding new scriptural and visual commentary in the wide borders around each image on the printed page. He also created a new image as the cover for the set, depicting the Seven Eyes of God, representing successive historical phases of religion and the awakening human mind (above).34

Linnell sold out the first edition of 315 sets, then printed a second edition of another one hundred sets of engravings, making a total across two editions of around 415 sets, sold originally at a trade price of £2 12s 6d. The project was eventually a commercial success.35

The Legend of Job

I’ve contrasted the Job story generally with Blake’s interpretation of it, but it needs emphasising again that the Job story itself is far from being reducible to the words of the Old Testament. In fact, the Job tradition as a whole is made up of a series of interlocking, overlapping and contradictory stories and images. The Book of Job was an amalgam from the start, based on a traditional Canaanite folk story, as mentioned above;36 the story of Job originated in folk tradition before it was written up by the Job poet, probably sometime around the end of the Babylonian exile and its immediate aftermath in the 6ᵗʰ or 5ᵗʰ century BCE.37 The story then continued to develop outside of the Bible among Jews, then Christians and Muslims, generating a wider Job tradition rooted in the Bible text but developing independently of it.

For instance, when the Gospel of James celebrates Job for his patience (making it proverbial, until it swamps the popular understanding of Job today), the author is almost certainly influenced not by the Old Testament Book of Job but rather the later, apocryphal Testament of Job, which argues that “patience is better than anything”.38 By contrast, the Hebrew words for ‘patience’ (erek) and its root (arak, ‘long-suffering’) are not to be found in the Book of Job.39 The so-called ‘patient Job’ was originally more of a militant and an iconoclast, challenging God to explain his suffering. His reputation has been whitewashed in popular culture.

From the town dump to the calvary of Christ

The Testament of Job was likely written by members of an ecstatic Egyptian sect, the Therapeutae, between 200 BCE and 200 CE.40 The story it tells differs in details from the Book of Job and lacks its convulsive poetry and radical theodicy.

The Testament is significant at this point because, when Blake painted his original image of Job and His Daughters (above, left), he showed Job dictating his story to the daughters. Behind Job on the wall are panels showing scenes from his life, towards which he gesticulates, his arms in a cruciform pose recalling Christ and the idea of Job as the ‘type of Christ’ / Jobus Christi.41 (through whom, according to Victor Hugo, “the dung heap of Job, transfigured, will become the Calvary of Christ”).42

This image was first created for the set Paintings Illustrating the Bible (1799-1803) but retroactively added to the Illustrations to the Book of Job when Blake was working on the Linnell set fifteen years later. Yet the idea that Job’s daughters were the first to record his history is not taken from the Book of Job: The Testament, on the other hand, claimed to have been written by Job’s daughters at Job’s dictation.

Blake's Job therefore draws on the alternative tradition of the Testament. This is just one example of Blake’s doing so. Lindberg thinks that there is the same influence on show in aspects of images 3, 5, 6, 14, 18 and 19 too, and that “the sense underlying Blake’s interpretation of the Book of Job, that our true life begins after death, is strongly emphasised by the Testament.”43

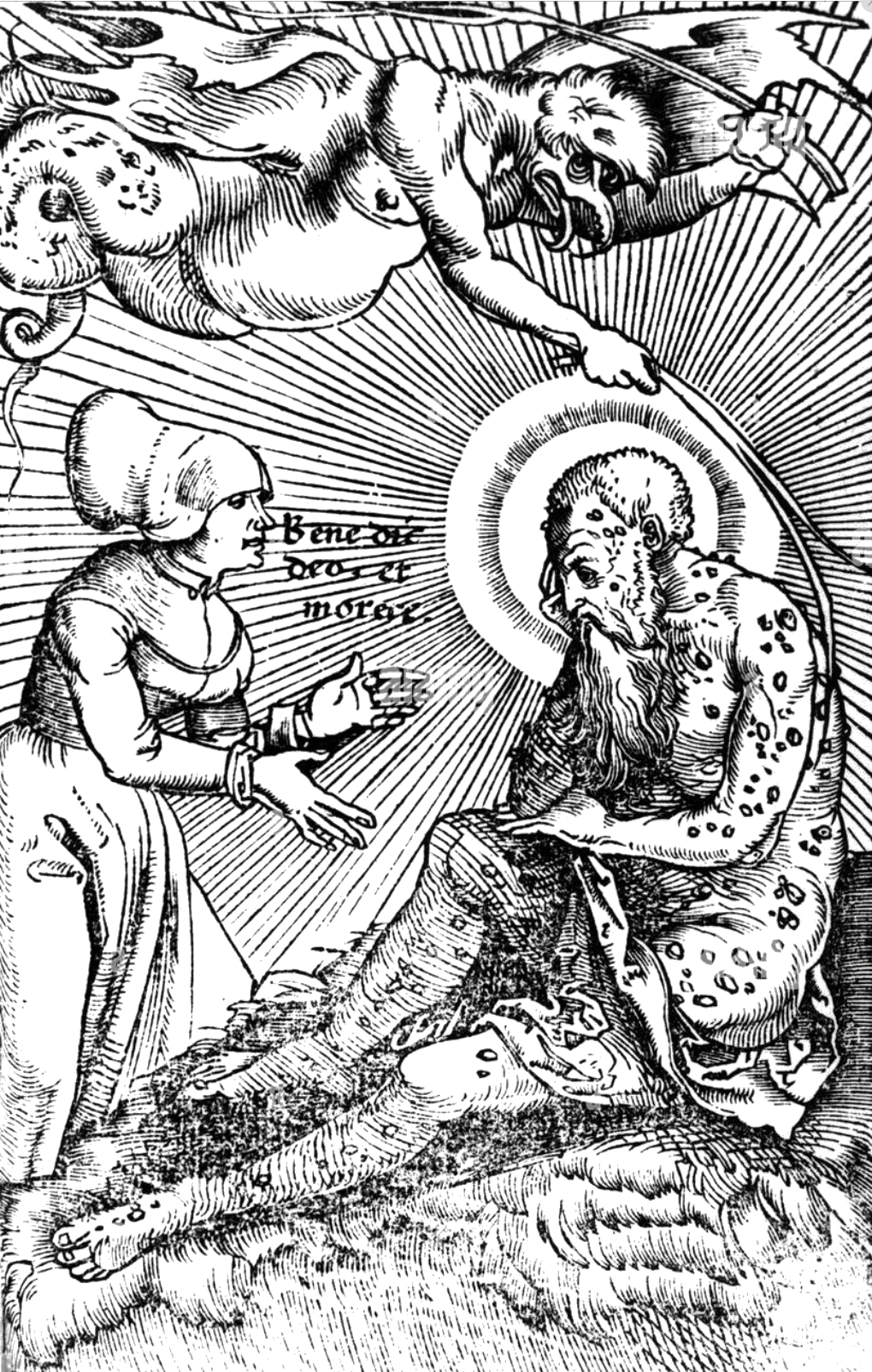

Blake cannot have read the Testament because it was not published in the West until 1833. But before then, “it had spread to the West in the form of folktales and poems, and part of its contents are preserved in German and English poetry, and in a French mystery play. Paintings and woodcuts illustrating the Testament are numerous, especially in the 15ᵗʰ century.”44

There are many other clues in Blake that he was familiar with wider folk and church traditions concerning Job, and incorporated legendary material into his art as well as inventing purely new scenes of his own. Many, if not most of Blake’s borrowings from the Job legend would have come to him through his lifelong study of pictorial traditions in Western art.45

True art and religion

In plate #1 Blake depicts Job and his family in front of a Gothic cathedral. Wicksteed and others claim that the significance of the Gothic in Blake’s art is that it is used to symbolise “true art and religion.”46 As Lindberg points out, such a meaning flies in the face of everything the plate is trying to say:

The Gothic church has been called a symbol of true art and religion... I do not think that symbolism to be Blake's. True art or true religion possessed by Job in plates one and four tends to make nonsense of Blake's picture story, in which Job achieves true art and true religion in the last scenes only.47

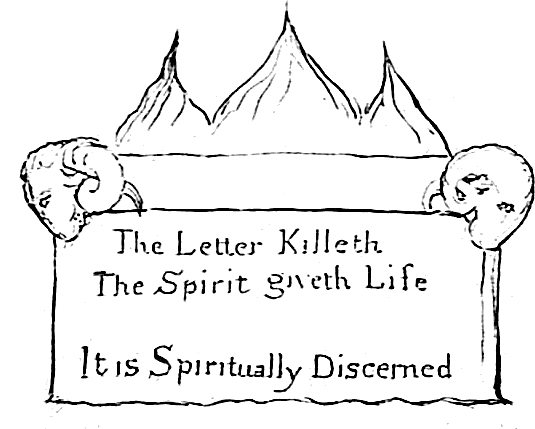

Job is shown at the outset of the story as being immersed in false religion and ignoring art: the family’s musical instruments hang in the branches of the tree, unused, indicating that true art and impassioned worship are missing from their lives. Blake makes this plain by adding to the engraved plate the text of St Paul’s warning to the Corinthians, “the Letter killeth, but the Spirit giveth life” [Corinthians II 3:6].

Job and his wife read the books of law on their laps (Blake used books to indicate law and reason, and scrolls to suggest poetry) because they understand God only through his laws. They have a limited understanding, and they certainly do not embody (at least at the outset of the story) ‘true religion’. That comes later.

Alien and anachronistic

In these circumstances, it makes more sense to think that Blake put the cathedral in the background because he had heard of the tradition that Job had been a bishop, which would suit Blake’s anti-clericalism (since the bishop here is not a true Christian) but, of course, it is entirely foreign to the original, pre-Christian setting of the Book of Job. In any case, this looks like another detail in which Blake relies on an extra-canonical source.

It is worth taking in just how completely alien is the opening of Blake’s version of Job compared to the original. Job is situated by a cathedral, in a Christian context. Job is implicitly criticised for following the letter of the law rather than its spirit, and thus of being a dubious, naive believer, just as Paul criticised those who thought Christ could only be approached by those who kept the Jewish law. It is the Spirit that counts, not the law.

Job’s situation is anachronistic. He is goaded by Blake to accept the spirit over the letter of the law, yet the spirit, the Gospel, did not exist in his time, and was not an option. His situation is doubly ironic for those who believe the Book of Job to predate the Exodus from Egypt: in that case Job lived not only before the Gosel but before Moses received the Law too.

Spirit over law

The emphasis on Spirit over the Law is at the heart of Christianity. It is therefore hardly surprising that it is also at the centre of Blake’s thought… but it was an alien concept to the Job poet.

Blake inserts Job into a Christian context then critiques his Christianity as well-meant but carried out by rote and not from the heart, so that it is therefore lacking. This is at the heart of Blake’s telling because it sets the scene for the eventual transformation of Job’s relationship to Yahweh, recognising Christ in God, and thereby overcoming this inadequacy. The original story has no role for Christ, for the obvious reason that it was written more than half a millennium before he lived, and was set at least another five hundred years before that. The original tale is about many things, but it is surely not about how to set oneself right with God by recognising Christ. None of this means that Blake was wrong.

Andrew Wright summarises the gulf between Blake and the Job poet over the fundamental meaning of Job’s experience:

The Book of Job raises the question of suffering and leaves it unanswered on the grounds that God cannot be held accountable to man: the voice from the whirlwind comforts but does not enlighten Job... [He] is rewarded not because he comprehends but because he endures. To Blake, however, Job's failure to understand is rooted in an infirmity of imagination. Job is guilty of refusing to look, of contenting himself pridefully with a superficial apprehension of the world.48

This shift upsets the theodicy of the story because, originally, Job was innocent, whereas Blake’s Job suffers because of his banal and religiose attitude. It cannot be that the suffering of an innocent man is the same thing as the suffering of someone caused by their being out of step with God. Blake puts Job in the wrong, though he was far from being the first to do so.

Types of Christ

That Blake should choose to reinterpret the story in this way is not at all unusual, given the Christian tradition of reading the Old Testament ‘typologically’, so that its events foreshadow and predict Christ’s coming: so, for example, Jonah is considered a ‘type of Christ’ because, in escaping the belly of the whale, he escaped death; when Yahweh looks favourably on Abel’s sacrifice of the firstborn lamb of his flock, he is recognising that the ‘firstborn lamb’ is a typological stand-in for Christ, firstborn of God.

If Blake had simply rendered the original story we would perhaps be less interested – not because the original is a less interesting story, but because it isn’t Blake’s story. Blake accepted the typological approach that creates a unity of the entire Bible by seeing it as all essentially about Christ. Not only is this orthodox, it is at the heart of Blake’s idea of the divine. He saw the Bible as telling a single, unified story, and his only ambition was to properly tell that story: he “held the whole canon as total truth and totally true“ (Martha England).49 But for Blake, the meaning of Job is bound up with the example of Christ in a way that cannot be true of the author of the Book of Job.

Non-canonical stories about Job can be found in both Palestinian and Babylonian versions of the Talmud.50 Other textual sources feeding into the popular image of Job that Blake might have drawn upon include the Mishna (a collection of Jewish oral traditions) and the Targum of Job, an Aramaic version of the Job story from the first century BCE, complete with commentary, discovered at Qumran. I’m not suggesting that Blake drew directly on these particular texts, but they prove that the legend of Job was not uniquely tied to the Old Testament, and that it developed in parallel to it in other contexts.

A prophetic, ranting Job

Blake, of course, would have known all about Milton’s use of Job in Paradise Lost, Paradise Regain’d and Samson Agonistes. As is clear from his comments about reason and energy in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he understood that Paradise Lost was a kind of retelling of Job’s story. As Stephen Vicchio says in his overview of Job literature, The Image of the Biblical Job, "... in Milton we see a rather curious and brilliant reinvention of the Book of Job."51

How unlike Blake not to have chosen a prophetic, ranting Job.

Milton depicts Job in line with tradition as ‘patient Job’, which surely influences Blake’s view – though I wouldn’t be the first to wonder how Blake really felt about Job’s legendary forbearance, being personally someone who liked to remind himself that "the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God."52 You’d think Blake would find the patient Job a bit bland for his taste. Curiously, this means that the indignation that characterises the original Job is underplayed in Blake’s telling, coming into play only in image #8: ‘Job's Despair’. How unlike Blake not to have chosen a prophetic, ranting Job.

In any case, there were plenty of sources of knowledge of the legend of Job available to Blake, and Job also appeared prominently in art and literature long before Blake’s time. Some aspects of the story had already condensed into legends, while others were still disputed and made new by each new generation of theologians and moralists.

The Book of Job was subject to commentary by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, St Jerome, St Augustine, Gregory the Great, Maimonides, Martin Luther, John Calvin, Spinoza, and Moses Mendelssohn, as well as literally hundreds of assorted lesser lights.53 The results of their deliberations were broadcast from pulpits across Europe since long before anyone could remember: Calvin’s commentaries are based on a run of forty sermons he delivered in 1554-55 on ‘aspects’ of Job’s tale; concluding characteristically, in the interests of social peace, that “... we must learn to keep our mouth shut when God afflicts us.“54

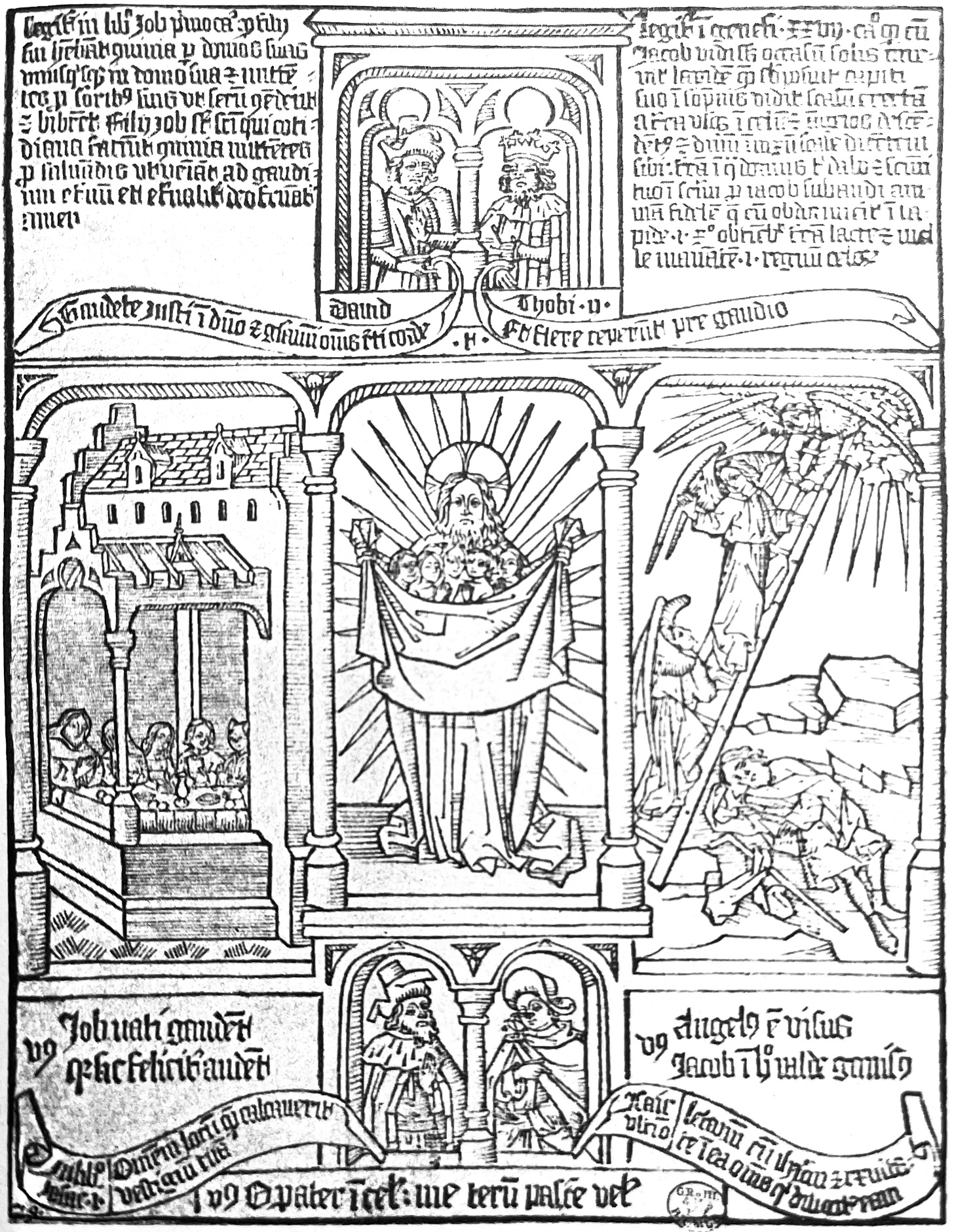

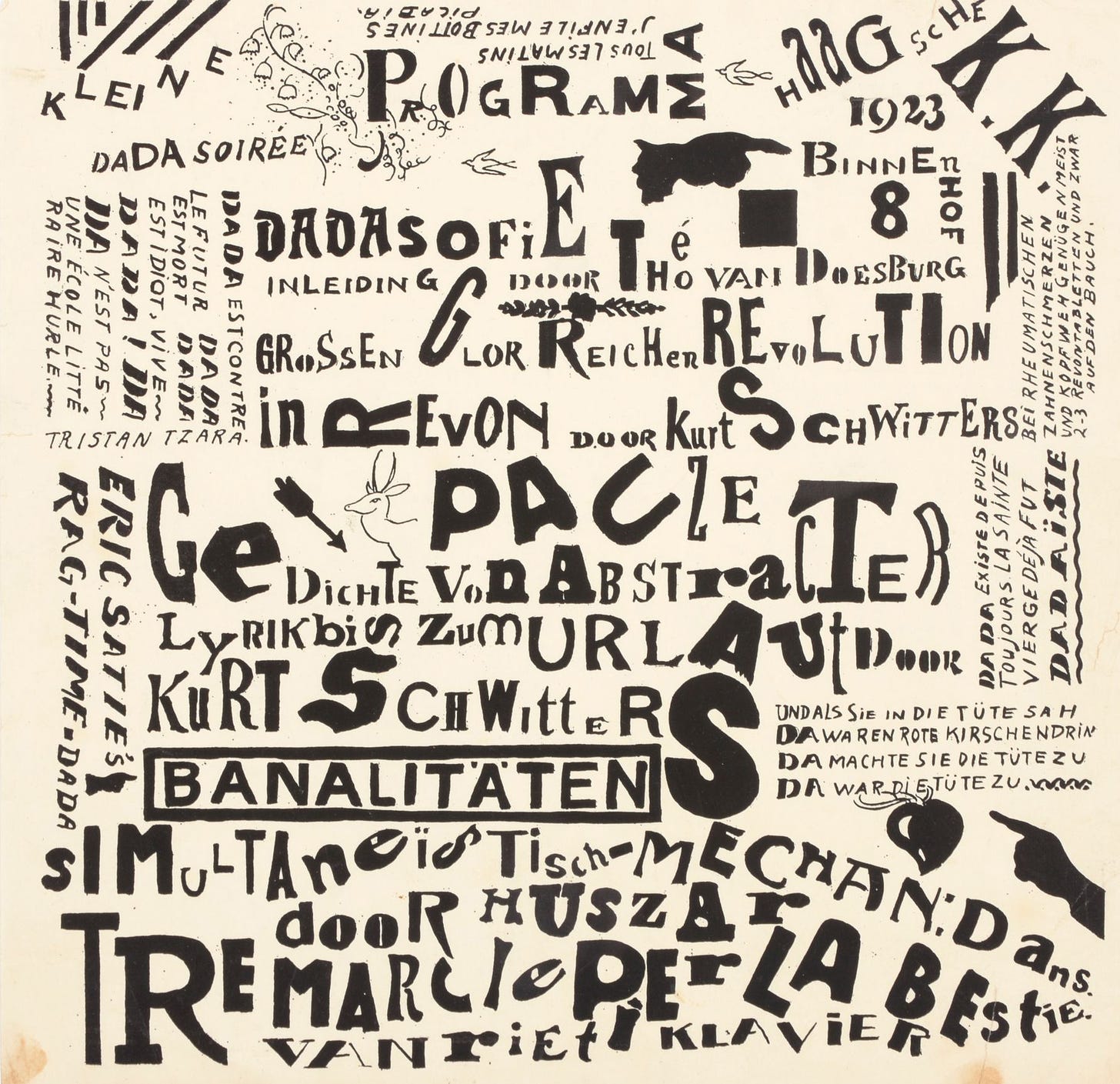

From the Bible of the Poor, via Blake, to the Wake

As much as any of this intellectual debate and criticism, among the key media shaping the perception of Job historically would have been the representations of his story in church murals and stained glass windows, and in works such as the Bible of the Poor (of which many competing versions were published), in which episodes from the life of Christ were depicted topologically in elaborate frames on each page, with scenes from different corners of the Bible appearing in the surrounding panels, so that each image reflects back and forth on the others, mutually supporting one another. Even in regular Bibles, the role of images was not merely to illustrate the narrative, much as is the case with many of Blake’s illustrations.

The typological approach – in which scenes of very different orders, trivial and grand, are connected across centuries of time – and the collaging of diverse texts and images on the same page, makes the Bible of the Poor a model of the type of non-linear narrative Blake would create with the mixed-media of his Illuminated works and which James Joyce made the tissue of Finnegans Wake.

Through such means, the elements of the Job story were transmitted, not always as a continuous narrative with a clear linear structure and a plain moral, but as atoms, molecules, and cells of meaning resonant with connections to other stories in the Bible and to everyday life, and all linked to the story of Christ’s promise of Job-like redemption.

For a long time, most people didn’t have access to a Bible. Even if they had, most of them couldn’t read it. Much of people’s knowledge of the Bible in pre-literate cultures was not strictly conceptual or discursive but absorbed in terms of images depicting events that were themselves the words with which God writes history.55 A brief glance at the Bible of the Poor reveals that its dramatic visual and textual contrasts and juxtapositions, and the way its elements call out to one another, create a similar web of intertextuality to that of Blake’s greatest works.

[The Book of Job] is an epic representation of human nature, and a theodicee or justification of the moral government of God, not in words, but in its exhibition of events, in that working, that is without words.

Johann Gottfried von Herder56

Polysemia at home

In this understanding of the Bible, each event is significant in and of itself, but widely separated events may also be relevant in conjunction or in contrast with one another, their meanings bound together typologically. From one point of view, the events unfold in linear order in time; from another, the events of Job’s story happen simultaneously and are still happening. In theodicy, virtue and reward must be arranged sequentially, laid out neatly, to make a point about God’s providence; but in the real world they exist side by side, much as they existed in the imaginations of those who got their idea of Job from devotional images.

Blake has woven these images together in his narrative, and his visions also call back and forward to each other, and to the original text, quite irrespective of how they are fixed on the plate. The autonomy of the individual Job image embodies a force, constantly threatening to prise apart the structure Blake places around the images as a whole. No matter how sublime Blake’s allegory, it can never exhaust the meaning of the original story, because that story is full of so much ambivalence and so many contradictions, and each element of the story is itself capable of being endlessly reformulated. Job’s story cannot be primly reformatted by Blake or anyone else.

In no way is this meant as a criticism of Blake. All narrative representations of the story of Job are faced with the fact that the legend of Job in its totality is more encompassing than anything they might invent to encapsulate it. If we bear this in mind, we are safe to start on the task of describing the myth that Blake built on top of Job.

Before describing the Blake illustrations individually we need to consider some issues to do with the structure of the images as a collection, as well as addressing the question of Blake’s use of symbolism in those images in the Job series specifically and in his art more generally.

Blake’s vision of Job

Joseph Wicksteed, author of the first long study of Blake’s Job (1910), argued that Blake’s cover for the engraved set reveals the overall structure of his story, based on Blake’s interpretation of the Prophet Zechariah’s ‘seven eyes of God’.57 According to this idea, Blake equates each of the seven eyes with a deity at the head of an associated religion, each of which religion is appropriate to one of the seven ages through which God attempts to awaken the sleeping Albion. This schema is often presented as the key to Blake’s Job.

Lucifer, Moloch, Elohim…

Blake names these deities Lucifer, Moloch, Elohim, Shaddai, Pachad, Jehova and Jesus; “the ‘eighth eye’ he occasionally speaks of is the apocalypse or awakening of Albion himself.”58 The first three ages are those known to Hesiod as the silver, bronze and iron ages, and these three ages are those of the Fall.

And they Elected Seven, calld the Seven Eyes of God;

Lucifer, Molech, Elohim, Shaddai, Pahad, Jehovah, Jesus.

They namd the Eighth. he came not, he hid in Albions Forests

William Blake59

Foster Damon elaborated on this to argue that each of the seven deities listed above governs the meaning of two plates in turn of Blake’s Job; so Lucifer has plates one and two, Molech, three and four, and so on up to Jesus, with plates thirteen and fourteen. After that, he argues, the deities each have one more plate to explain, but the order of deities is reversed; so Jehova has plate fifteen, Jesus plate sixteen, Pahad plate seventeen, and so on up to Lucifer again for the final plate, twenty-one.)

Despite this scheme having become an accepted template for interpreting the Illustrations, Foster Damon has to tinker with the story itself and with the order of the eyes as well (you may have noticed in the description above that he arbitrarily swaps the positions of Jehova and Christ when assigning plates fifteen and sixteen, for instance) to come anywhere near Blake’s images. Lindberg argues that this system of the seven eyes doesn’t help understand Blake’s story in terms of its theology, its linguistics or the pictorial reading it encourages.60

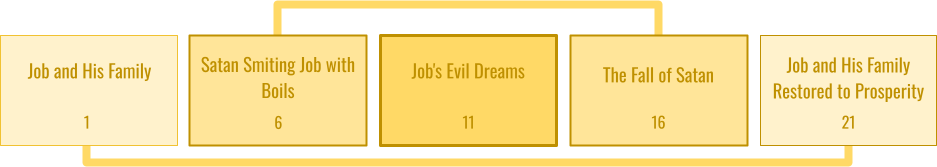

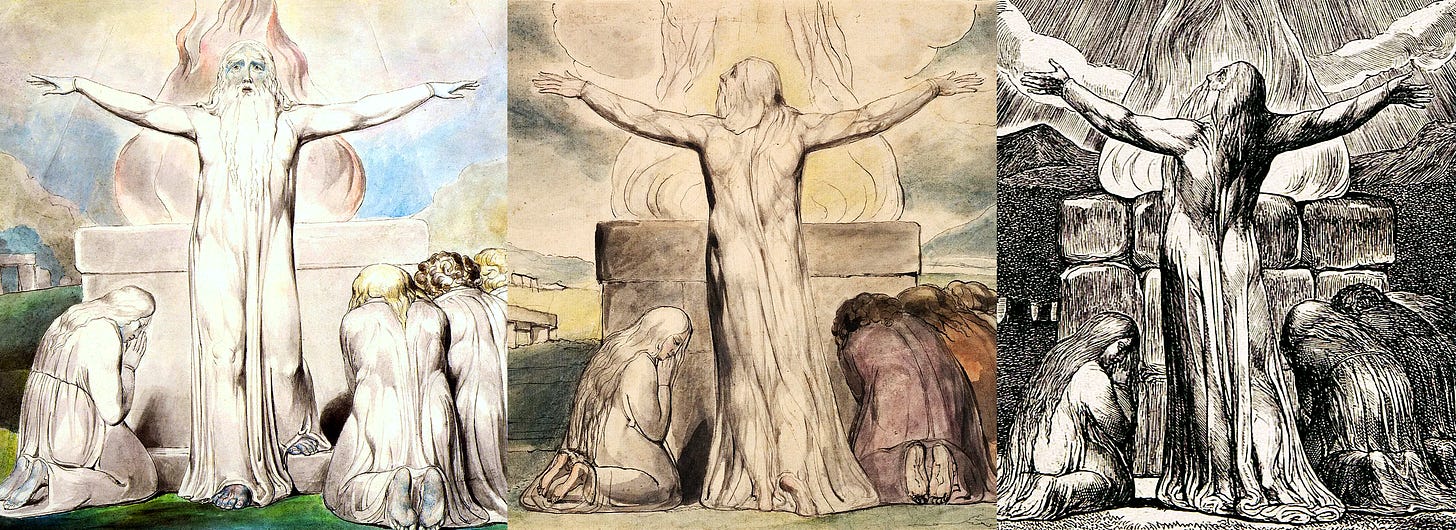

Instead of this overarching explanatory structure to Blake’s story, Lindberg argues for a simpler breakdown, with each fifth image representing a turning point. This is a keyframing structure in which the first, sixth, eleventh, sixteenth and final plates are the keys, while each set of four plates separating the keyframes provides context for the main images or moves the story along.

So, the keyframe structure is: 1+4+1+4+1+4+1+4+1 (the keyframes are marked with a kappa, ϰ, in the titles when the individual images are discussed below). This means that Lindberg thinks images one, six, eleven, sixteen and twenty-one are the most important plates (see above). Note that this structure does not impose a particular meaning on either the series as a whole or the individual images, only on how the telling of the story is paced, and the emphasis placed on different parts of it. The most it requires is that the keyframing images are treated as especially telling for the story’s development.

Another point about the structure of Blake’s story is that it is entirely of Blake’s making. While many of the events of his story appear in the original, they are not necessarily in the original order, and some of the scenes are Blake’s invention. “The order of the designs was invented by Blake and does not follow the events of the book. It is original, not illustrative.”61

Job’s unity

It is worth emphasising that the Illustrations to the Book of Job form a unity; “The series forms an epic unity, and is conceived as a whole” (Lindberg).62 What this means is that the collection of the images taken as a whole, considered in the order in which Blake arranged them, tells a story unified teleologically by the point Blake is trying to make about the nature of the divine. The continuity between images is asserted by the manner of their arrangement and by the use of common motifs. To change the order of the images would be to change the story and the point of the story.

But this undoubted unity does not mean that the individual images in the series are meaningless outside of the totality constructed from them by Blake’s sequencing, design, and (with the engravings) commentary. This is true by analogy with the way that we can say that a page of the Bible of the Poor is not exhausted by thinking of the message of the overall design of the page, its theme, but also contains image and text elements with a life of their own, affecting the viewer independently of, or in addition to, their contribution to the whole. The individual image is not subsumed by its part in the series.

Where Blake’s Job is most coherent and most structured, is in the primary level of meaning of the story, aimed at the casual buyer. Where it is less structured is everywhere else.

Implicit and explicit work

This creates a tension in Blake’s work. On the one hand, spotlit on centre-stage is the narrative he wanted to create; the meaning or sense he consciously and artfully designed to share with his audience (the explicit work). This meaning can be inferred by adopting the point of view of Lindberg’s ‘educated observer’ and reading the visual and textual cues appropriately.

Sitting alongside is a parallel work, or indeed parallel works, authored by Blake’s unconscious and his habits, constructed from the same images and text elements as the other levels, but created spontaneously by Blake in response to his knowledge of the Job tradition, to express ideas he himself may have been only more or less aware of; the implicit work(s). Just as the character in a novel may import a backstory from elsewhere, Blake's themes and characters may have lives outside the Illustrations. The implicit work doesn’t cohere in the same way as the explicit. It may agree with the latter in some details, in others it may be at odds.

Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job should be studied to extract all the sense we can from it concerning not only Blake’s intentions but also his underground, implicit knowledge. The Lindberg framework is useful in deciphering the explicit meaning of the work, to do with Blake’s beliefs and intentions, but it is irrelevant when we look at the implicit meaning. I have found it useful to keep the five keyframes in mind when thinking about Blake’s telling of the story. It will not always bear more weight than that.

I treat the Butts and Linnell sets and the engravings as equivalent. The two sets were not created as trial runs for the final work somehow embodied in the engravings: in that case, the engravings would rightly be considered the definitive work for which the watercolours and sketches were only preparations. But, with the small exception of Job’s changing posture in different versions of image #18, ‘Job's Sacrifice / Job Praying for his Friends‘, there are no significant differences between the earlier watercolours and the final watercolour copies and engravings. The original Butts set is the definitive work: the Linnell sets and the engravings are copies, and copies of copies, of the Butts set.63 They were not attempts to improve on the originals, but to duplicate them.

The exception here is that Blake added significant commentary by way of added design elements and (usually) Biblical quotations in the margins of the engraved images. These clearly throw light on Blake’s intentions at each stage, and I’ll draw on them as appropriate. Other than in the matter of colouring, I discuss details of the images irrespective of which set they are from (watercolour sets, sketches or engravings) as they are essentially the same, certainly as regards their symbolism. I have mostly illustrated these notes with images from the Butts set.

#1: Job and His Family (ϰ)

This scene has been mentioned already: the significance of the cathedral, placing matters firmly in a Christian context, and the implication that Blake’s view is fundamentally not realistic or historical but typological, was noted. This holds for the entire series of images, not just this one, and it’s worth emphasising that this typological view is not just a way of interpreting the Bible, but the basis of Blake’s Christianity itself.

The image depicts the status quo ante. Job and his wife are pious and respectable, with their children and flocks alike arranged dutifully around them. Job and his wife both are reading books: in Blake’s iconography, books are identified with law, judgment and restriction, and are contrasted with scrolls, representing inspiration. The instruments hanging uselessly in the tree signify an absence, or attenuation, of arts and the imagination. Job recites the Lord’s Prayer by rote (we assume, since it is engraved in the margins). As if the message of the scene were not clear enough already, Blake adds to the engraving a quote from Corinthians, “The Letter Killeth / The Spirit giveth Life” [2 Corinthians 3:6]. This is Blake’s theme.

The sun shines on everyone. The flocks advertise Job’s prosperity. All seems well, but there is a weakness in Job that will prove disastrous for him, namely that his piety is merely verbal and performative (“the letter killeth”), not from the spirit (“the spirit giveth life”). He does what the law requires – perhaps willingly, possibly even enthusiastically – but his awareness of God stops at that limit.

Wicksteed says that “the whole design represents the ideal state of Innocence,” yet it comes across as barbed rather than innocent. To be fair, it is deliberately ambivalent. Most people will assume when first looking at it that it is a scene of rustic peace and simplicity, and only then will mark the signs that indicate that something is not right. Specifically, the image depicts a piety based on memory and adherence to the letter of the law, rather than imagination.

In relation to God, Job is not innocent, not “perfect and upright” – at least not in Blake’s telling. He is guilty of pride, says Blake. Such a situation can’t persist.

#2: Satan Before the Throne of God

Blake now conjures up an authentically Canaanite scene, with God shown holding court among his followers – the heavenly host, ‘bene ha Elohim’ – as the ancient Canaanites believed was the case, and as the Jews also believed during their earlier years in Canaan.

God and his allies on Mount Zaphon / Zion

The perspective has zoomed out to show earth and heaven together: in the original Ugaritic myth, the assembly of the gods was on Mount Zaphon; here the action unfolds in heaven.

I thought at first this might be why the Bible originally said Job was from ‘Uz’ – to allow the author to use this theatrical image of God and Satan debating in heaven about what to do with a mere mortal, like two cats squabbling over a mouse, as the people of Uz might have been held to have believed. But that wouldn’t satisfy a Jewish or Christian reader as an explanation for Job’s troubles, so we can only conclude that the Jewish compiler / author of the Book of Job saw it as compatible with Jewish belief to depict their supreme deity as the leader of a tribe of divine beings, of inferior status but similar stature to himself, among whom is the accuser, ha Satan.

The nature and hierarchical status of the members of this heavenly host has long been debated. According to the Canaanites, they were simply their other gods, among whom their supreme god, El, was first among (almost) equals. They were known collectively as the ‘Assembly of El’. It seems that at some point the Jews felt similarly for a while, and placed Yahweh at the centre of the same retinue, but they backed out by gradually evicting the lesser deities from heaven, demoting them to the status of cherubim or demons, while at the same time promoting Yahweh to unprecedented heights, as the one and only God on high, his peers cast off behind him like the abandoned rocket stages in an Apollo moon launch.

It’s clear that at the time of the story’s telling this separation between God and his heavenly supporters had yet to happen, and the heavenly hosts of the original Job text retain something of their original independence.

Subsequent commentators dealt with the problem of the status of the host members in a number of ways, making them angels (Thomas Aquinas, John Wesley and others), fallen angels (Olympiodorus, Irenaeus, Eusebius, Tertullian), sons of the gods (Philo), Cherubim (Philo of Alexandria), angelic lords (Rashi), and so on.64

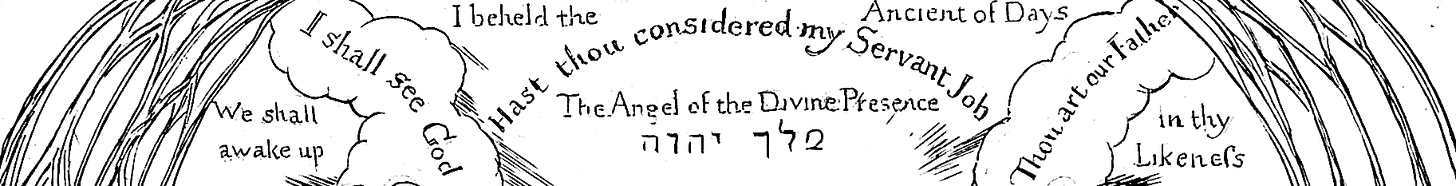

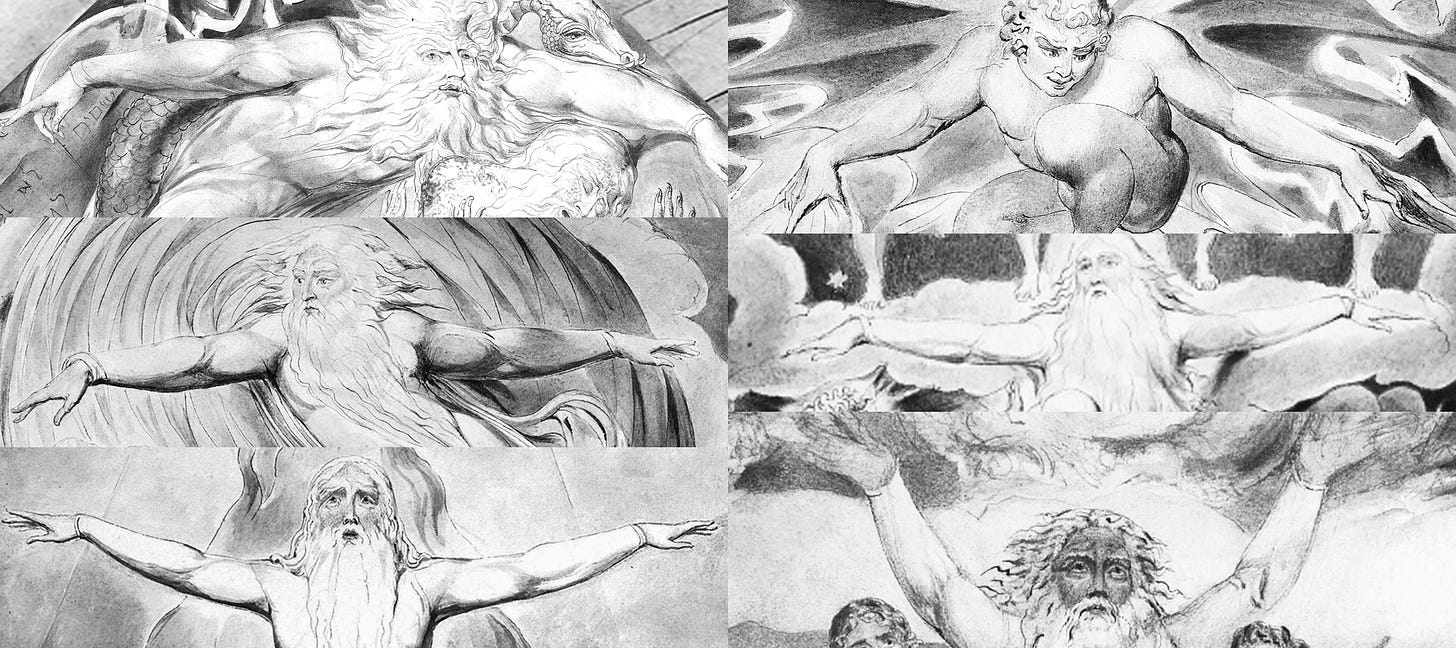

Ancient of Days

At the head of the engraved plate for the image, Blake mentions seeing the Ancient of Days (see above), a figure who then transfers directly into Blake’s mythos and who he famously painted and engraved many times.

In the Old Testament, the Ancient of Days is mentioned only once, in the Book of Daniel: “I beheld till the thrones were cast down, and the Ancient of days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire” [Daniel 7:9]. This is who Blake has in mind here, dragging him into the Job story and his own mythos alike:

God is represented as the Ancient of Days and posseses white hair, ie. he is depicted as an old man. This is unique in the entire Old Testament. It agrees admirably, however, with the supreme god of the Ugaritic pantheon, El, who is called 'ab šnm, 'Father of Years'... El was an aged god. (John Day)65

Blake imports the “supremely aged” deity, El, from the oldest Ugaritic pantheon and makes him an icon of his own system.66 The fleeting appearance of the 'Ancient of Days is one of those little flashes in Blake’s work where we see the Ugaritic myth peak through.

Wicksteed said that God here looks like Job’s twin brother, and concluded that Yahweh was made in Job’s image and was therefore the creation of Job.67 Even if we accept that there is a likeness here (plenty of people are quick to point out that all Blake’s old men look similar anyway), we do not have to give in to those who, psychologising Job, think that Yahweh is merely Job’s authentic self. Chesterton pointed out that it would make sense for Yahweh to resemble Job since the latter was made in God’s image anyway, as all readers of the Bible would know.68

The faces of Yahweh

It is always best to tread carefully with Blake, even when you think you are on safe ground. In this case, while Yahweh may be Job’s inner God as well as his creator, and therefore identified with Job, things can get confusing when Satan adopts Yahweh’s role or steps into in his place. On top of that, the Church Fathers agreed that any direct vision of God, such as that of Moses and Job, was an experience of one of the divine attributes of God (The Word, Logos, Wisdom), and therefore essentially a vision of Christ.69

Back down on Earth, in the lower part of the image, Job is sat with his wife and their books, as before. Things there seem unchanged, but in heaven the ball has started rolling. The Jungian psychologist, Edward Erdinger, describes Blake’s design here as showing “an intense dynamism [approaching] Yahweh… Satan, the autonomous spirit, manifests in a stream of fire. As the urge to individuation and greater consciousness he stirs up doubts and questions which challenge the status quo and destroy the complacent living by the book.”70

Note the two faces engulfed in Satan’s flames, one under each of his armpits. I can only assume, as most others do at this point, that these are the spectres of Job and his wife – their pride, “the reasoning power in man.”71 The same spectres are seen departing alongside Satan later on, in image #16, ‘The Fall of Satan’, dropping headlong into the lake of fire on either side of him, so I assume they are here being brought on stage alongside him too, so that this image forms a pair and a line of continuity with #16.

Symmetry, pairings

This mirroring between plates is reminiscent of the pairings between poems in Songs of Innocence and of Experience. The mirroring between images #1 and #21 – the first and last images of the seriesmight as well be titled ‘Job Lost’ and ‘Job Found’, after the poems ‘The Little Boy Lost’ and ‘The Little Boy Found’.

Such obvious symmetries as those between the first and last plates are quite neat and might be designed to appeal to the mind of the average buyer, lending the work obvious structure, or encouraging it to be seen that way. In other cases, the contrasts and inconsistencies between each half of the pair tend to multiply meanings and open up ambiguities that threaten the stability of the collection as a whole, as a simple structure. The continuities and reflections can serve either order (continuity implies connection) or disorder (the connections overdetermine one another, feed back, clash, conflict, trip up the narrative, and so on).

In heaven, the debate between Yahweh and Satan begins. In the engraving, comments are added in the margin; “I beheld the Ancient of Days” (see above), “There was a day when the Sons of God came to present themselves before the Lord & Satan came also among them to present himself before the Lord” [Job 2:1], and “Hast thou considered my Servant Job?” [Job 1:8] Yahweh and Satan discuss Job, with Satan challenging Yahweh, “put forth thine hand now, and touch all that he hath, and he will curse thee to thy face” [Job 1:11].

Eventually, Yahweh grants Satan permission to ‘touch’ Job and test his faith (though he is as yet forbidden from harming Job physically). The fact that such a wager takes place between Yahweh and Satan is a clue to how foreign this scene is to traditional Biblical theology: “God's quick acquiescence in the Adversary's perverse proposal is hard to justify in terms of any serious monotheistic theology” (Alter).72

The fact that Satan can dispute with Yahweh as a platinum club member of his court is interesting, but so are other features of the exchange. We learn that Yahweh is not all-knowing: Yahweh’s doubts as to how Job will behave under duress are authentic: he doesn’t know what the outcome will be. If you are one of those people who thinks that Satan and Yahweh are essentially gambling over Job’s future behaviour, you could say that it was a fair bet. No one knows what Job will do, except perhaps Job.

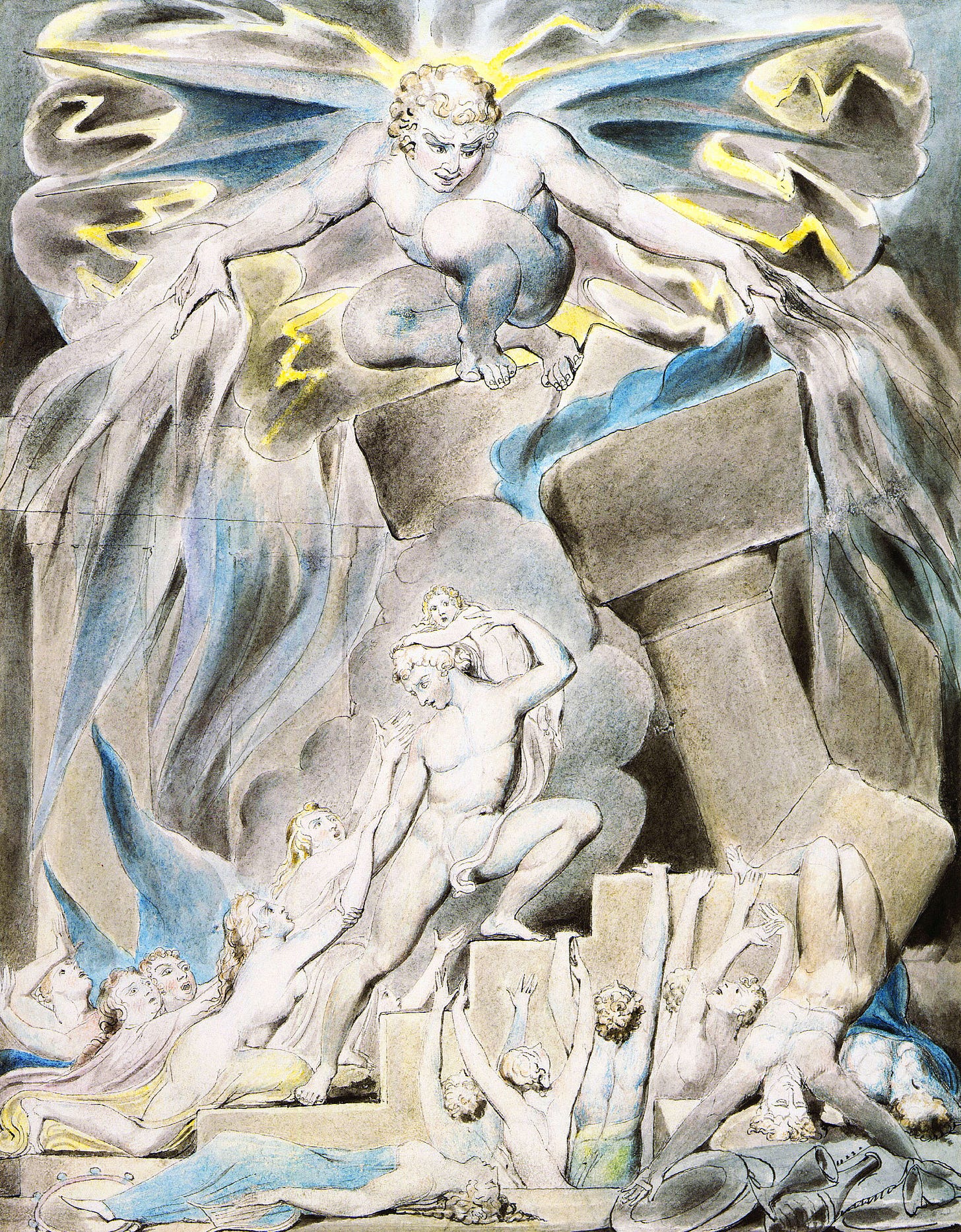

#3: Job's Sons and Daughters Overwhelmed by Satan

Can’t go on, I can’t go on

Everything I have is Gone!

Stormy weather!

Fats Comet

Satan’s assault descends on Job in several waves. Sabbean and Chaldean bandits and the “fire of God” attack his servants, his flocks and his property, killing the servants and stealing Job’s property away [Job 1:16]. The final blow lands in the form of “a great wind from the wilderness” that “smote the four corners of the house” [Job 1:18-19]73 of Job’s eldest son, where Job’s children had all been sharing a meal. The wind brings down the roof, killing all the children.74

The “fire of god” is not the only divine element at work here. The “wind from the wilderness” that flattens the house is not an ordinary wind. Destructive winds were well-known to the people of the region, used to both desert storms and storms at sea, but a wind that comes from all directions at once, striking all “four corners of the house” is a divine, or demonic, wind.

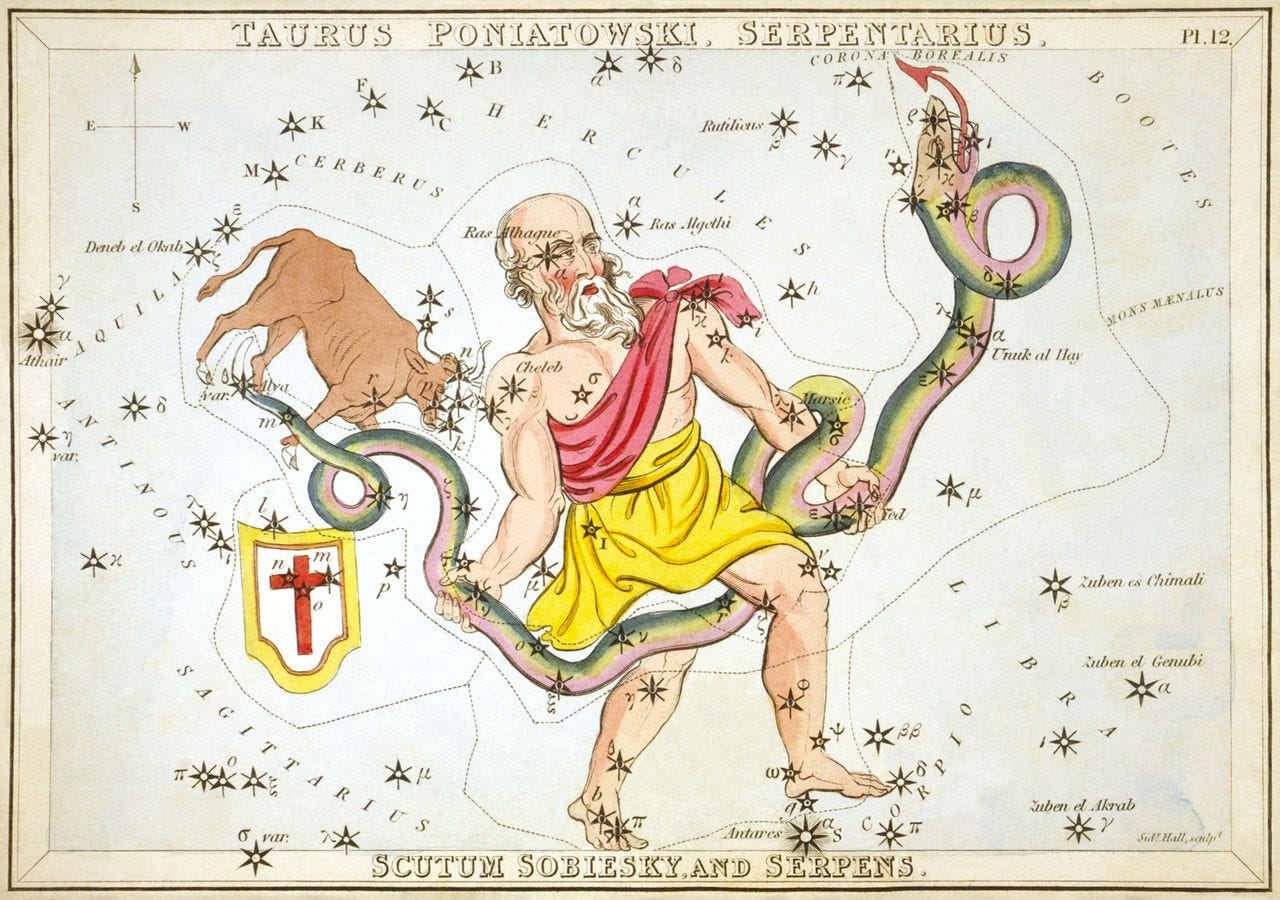

Canaanites in space

The people of Job’s time did not think of space as we have, since Newton, as an intangible, immaterial container for massy things to squat and roll around in: they felt space itself actually move in the winds around them. To be master of the four winds, of the four directions, was to master all of space, and hence it was synonymous with absolute power. It was god-like. Such wind-deities were often shown with four wings, representing the four directions. Ezekiel’s Cherubim are descended from these deities, their four wings allowing them to move effortlessly in any direction at any time, and thus they steer Yahweh’s chariot instantly in any direction, like a UFO.75

Powered by wind

We should note that Satan, as he takes the form of the “great wind” in this scene, has acquired wings, which he did not possess in the previous image, ‘Satan Before the Throne of God’. These are the wings of a wind, or storm god.

Such total power was naturally also connected, or allied with, the sun, the ultimate source of life and power, the worship of which was also a feature of primitive Jewish religion, with the winged solar deity even becoming a seal of the Northern Kingdom for a while (presumably thereby scandalising the notoriously touchy Yahwistic prophets). There isn’t room here to discuss Freud’s proposal that the Jews when they left Egypt worshipped Akhenaten’s sun god, the Aten. On the other hand, it is possible that any association between Yahweh and the solar deity came about not via the Aten, but rather at a later date by inheriting the solar aspect of the residing Canaanite god, El, with which Yahweh eventually merged.76

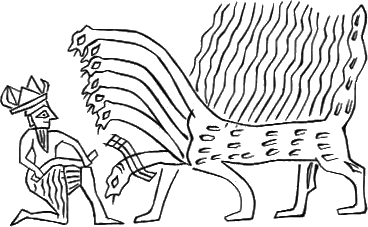

All we need note at this point is that the four winds together were associated across the region with the divine and the demonic, and also with the idea of a supreme god (whether Aten or El). We will hear more examples where the details of Job’s story turn out to have vital connections with the early religion of the region, and where Yahweh is revealed to share a common mask with Baal, Marduk, and other deities of the Near East celebrated for bringing the world into existence by conquering the chaos dragon.

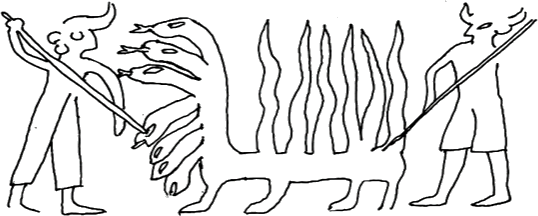

Chaoskamf

The war of the gods against this chaos monster at the beginning of time is known in Bible commentary and literature as the chaoskampf (the chaos war). The story of Job, above all books of the Bible, is saturated with intimations of this chaoskampf, which bleed through into Blake’s work and into his imagination.

In image #11, ‘Job’s Evil Dreams’ (ϰ), we will see that Blake, scandalously, pictures Yahweh merged with Satan, with cloven hoofs. Regarding the current scene, where a divine wind destroys Job’s children, we note that Yahweh was originally a storm god, suggesting the possibility that what is depicted here that looks like Satan is, in some sense, also Yahweh in his role as a storm god.77 If it is true that it is Yahweh-storm-god that kills Job’s children, then it must be Yahweh that is shown above, clearly looking thoroughly Satanic, destroying the building. The image of the winged Satan here would then be a more obscure precursor of the big reveal in image #11, ‘Job's Evil Dreams’ (ϰ). In both cases it is not always clear whether Satan replaces Yahweh, or merges with him, or stands in his stead, or what.

The architecture of this scene shifts from the Gothic to the ancient, with its great monoliths reminiscent of Stonehenge. The central figure seems both heroic yet somehow fundamentally aligned with Satan (look at the respective positions of their feet), perhaps like a puppet. The figure at the bottom-right has fallen into a crucifix posture.

#4: The Messengers Tell Job of His Misfortunes

In the original story, Satan’s attacks on Job come in waves, and each time a messenger arrives to tell Job of the latest blow, another messenger arrives hot on his heels with more bad news. Blake compresses the unfolding of the tragedy, and the announcement of each stage of it, into a single image, with a later messenger seen on his way even as the earlier messenger is delivering his share of the bad news to a grief-striken and astonished Job and his wife.

Psychologically, the power of this image lies in how it encompasses each of the successive blows Job experiences into a single combined blow, whose moment of impact contains within it the history of Job’s undoing, all of those previous blows, and we see it all being registered by Job and his wife. This is the point at which you might expect Job to shatter.

In the engraving, Blake adds as a comment the words of one of the messengers, “And I only am escaped alone to tell thee” [Job 1:15]: each time Satan ravaged Job’s world, he made sure that one person survived to share with Job the gory details of his losses.

#5: Satan Going Forth From the Presence of the Lord and Job's Charity

Satan is now calling the shots. Down below, Job continues to follow the letter of the law and, despite his troubles, is seen distributing alms. Job is morally victorious. Up above, it looks as though, as Wicksteed memorably puts it, “the contagion of [Satan’s] presence has infected the seraphs themselves.”78 Satan’s flames have spread to the rest of Yahweh’s court, which is disturbed. Yahweh himself looks depressed and joyless, but no more so than Blake, who looks forlorn despite his moral victory.

Fancy footwork

The positioning of feet is often significant with Blake, and there seems to be some point being made in the way the positions of Satan and Yahweh’s feet echo one another, with the left leg oddly extended and one knee raised. The concordance between Satan and Yahweh’s legs mirrors that between Satan and the most prominent of Job’s sons in image #3, ‘Job's Sons and Daughters Overwhelmed by Satan.’ There are some strange entanglements here. As far as I can tell, everyone else has their right foot forward.

This almsgiving scene is not from the Bible. It comes from a tradition in the early church that Job shared his last meal with a beggar.79 It was chosen by Blake to be included here to emphasise that Job remained true to his beliefs, persisting in his generous ways. Despite losing everything, he continues to give alms. The angels look on approvingly.

Did I not weep for him who was in trouble?

In the margin of the corresponding engraving, Blake engraves “Did I not weep for him who was in trouble? Was not my Soul afflicted for the Poor”. We assume it is Job asking the question, and that it reveals him to be a little self-righteous. This is a clue to the dialectical nature of the image. Blake emphasises the continuity of Job’s practice and implicitly calls on us to admire him for it. And yet his virtue in this regard is the greatest barrier to his rapprochement with Yahweh.

By clinging to an outward show of piety, Job prevents Satan from busting him for his shortcomings, yet it is the very nature of this piety, the fact that it is enacted in rote conformance with tradition, and not ‘in the spirit’, that is Job’s weakness. Job is celebrated for persisting in his ways: in fact he doubles down on them. Ironically, his consistent piety only confirms his distance from Yahweh. Something must give, and the anxious expression on Job’s face shows he is unconsciously aware of this.

Satan’s great talent is for spotting weaknesses like that of Job. Having done so, he continues to press his case until he gets permission from Yahweh to now attack Job also in his body. The demonic energy Satan smeared around heaven in the image above is about to be channelled down with renewed force onto his victim. Satan is about to really bring the fire on Job.

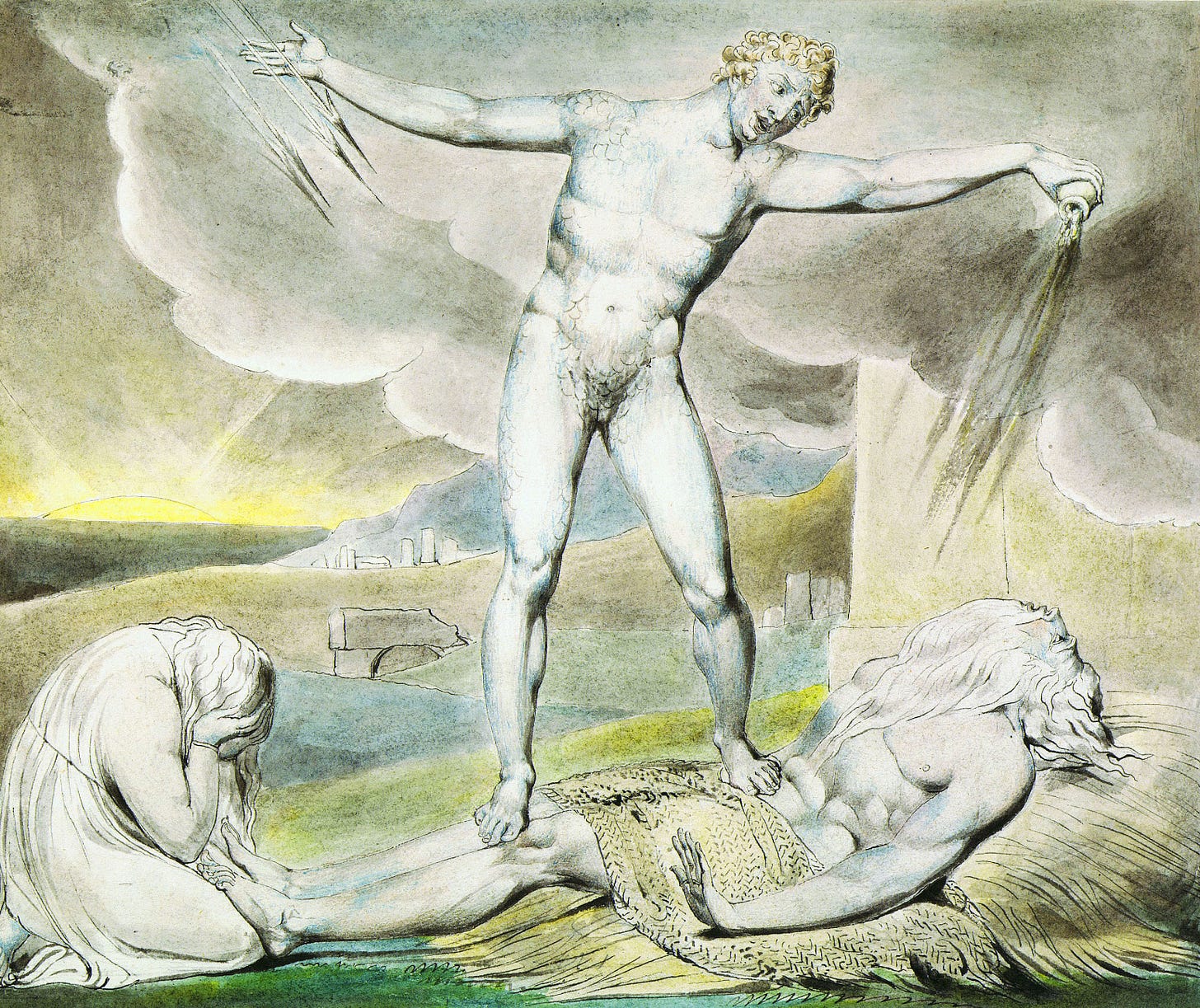

#6: Satan Smiting Job with Boils (ϰ)

In Bible-speak, ‘boils’ generally mean venereal disease / STDs,80 although there was also a tradition in other circumstances of seeing these boils as evidence of leprosy.81 For Wicksteed, the fact that Satan is standing on Job’s right knee is enough to prove that the attack on Job is actually ‘spiritual’, rather than physical.82 But is Satan standing on Job at all? He looks to be hovering a few inches above him. And even if he were standing on Job’s right leg, half his foot is resting on his left. What would that signify? Wicksteed is having a stab in the dark, and the legs are being worked too hard by him.

As with image #3, ‘Job's Sons and Daughters Overwhelmed by Satan’, the blues and yellows of this scene do a good job of manifesting Satan’s malice in action. Satan is seen to be pouring a dark infection on Job from the phial in his left hand. One can’t help but assume therefore that this image and the one immediately before, where Satan is also pouring the contents of his phial on Job, show two different perspectives on the same scene or situation.

An acute breakdown

For Erdinger, “This is the picture of an acute breakdown; all defences have collapsed. The picture shows Job being stricken with boils. In dreams boils represent festering, neglected complexes which are erupting into consciousness.”83

Additional designs by Blake in the margin of the corresponding engraving provide grist to the analytical mill:

In the margin below is the broken sheephook of Innocence, with symbols from the despairing last chapter of Ecclesiastes: "the grasshopper shall be a burden, and desire shall fail." The pitcher is broken at the fountain, which now is choked with rubbish…84

Samuel Foster Damon

The broken pitcher below the picture suggests that the ego as a container may break if more is poured into it than it can stand... According to [Lurianic Cabbala] the creation of the finite world required that the divine light be poured into bowls or vessels. Some of these bowls (the seven lower Sefiroth of the Sefirotic tree) could not stand the impact of the light and broke, causing the light to spill. This picture suggests that Job is such a vessel.85

Edward Erdinger

But, whether we psychologise the boils as sexual repression or treat them straightforwardly as the clap, whether we see the broken jug as a symbol of Job himself as a busted flush, or sublimate it into a vision of the Sefirotic vessels as the receptacles of the divine effulgence, in either case Blake is devastated by Satan’s new attack and brought to his lowest ebb. His jug is ready to shatter.