Phil Smith, Albion’s Eco-Eerie: TV and Movies of the Haunted Generation, Shrewsbury: Temporal Boundary Press, 2024.

Mark Fisher (1968-2017) founded Zero Books, Repeater Books and the k-punk blog. He was the author of Capitalist Realism and Ghosts of My Life, and taught at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Culture has lost the ability to grasp the present

Mark Fisher

If we gift them the past we create a cushion or pillow for their emotions and consequently, we can control them better.

Eldon Tyrell, Blade Runner.

Perhaps a better hour may at some time strike even for the clever fellows: one in which they may demand, instead of prepared material ready to be switched on, the improvisatory displacement of things.

Adorno

TLDR: A discussion about the details of Phil’s book quickly turns into a reappraisal of the work of Mark Fisher and his kin (Zero Books, Repeater Books, Nina Power, Nick Land, Simon Reynolds, David Stubbs, et al.) and their ideas of hauntology and the Ghost of Marx.

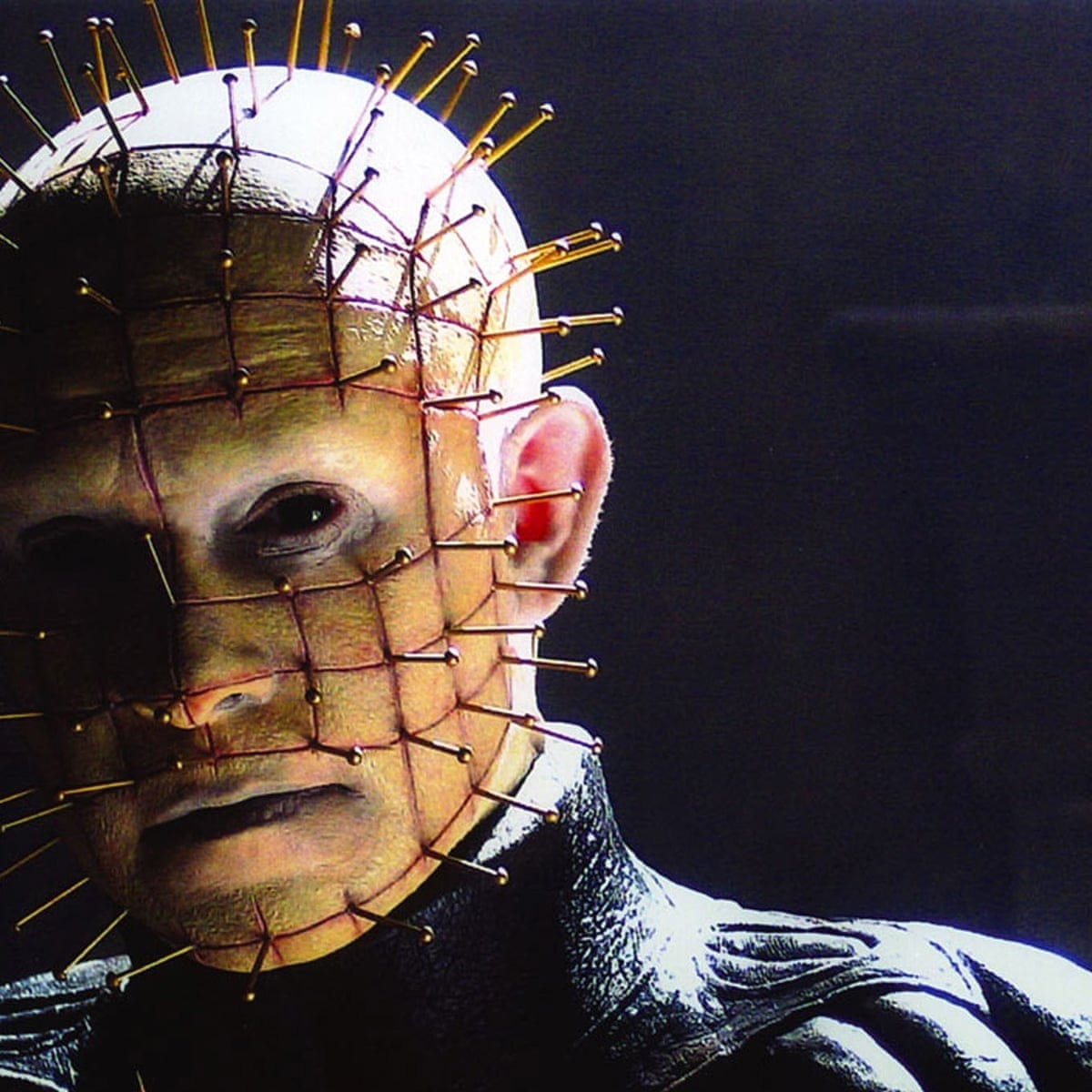

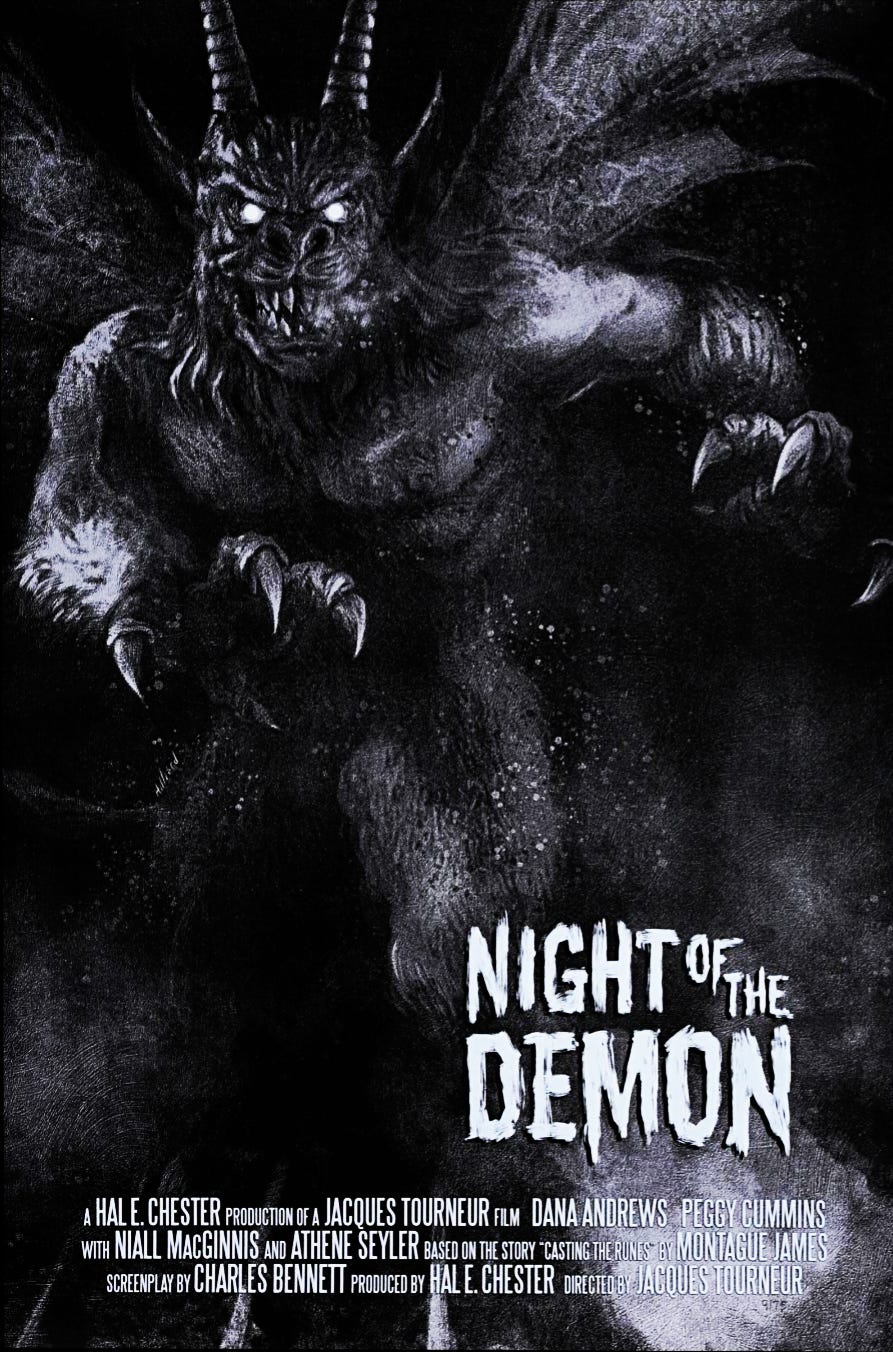

Films reviewed in the book include: Night of the Demon, The Company of Wolves, Fireball XL5, Quatermass and the Pit, O Lucky Man!, Children of the Stones, Whistle and I'll Come to You, Hellraiser, Hellbound.

It is a bold book that takes the weaving path of blood, trauma and sensuality away from Folk Horror and fashionable 'hauntology' into new, enchanted spaces. Digging up and doubling down on messy ideas and demon lovers that exist not to elevate us to transcendence but to immerse us in the mud of grotty instinct.

Stephen Volk, author of The Dark Masters Trilogy and Ghostwatch

Albion’s Eco-Eerie takes a deep dive into films beloved of a generation (mine)1 to grub out traces of ecological drift and ontic upset. The author insists that his is a materialist appropriation of hauntology, not just speculation about some idle flapping of the spirit, by which he seems to mean that he’s keen continually to return his gaze to material traces of past and future and the eruptions of the edge lands onto the plain.

traces of ecological drift and ontic upset

Stars of the show here, as they must inevitably be in any such line-up, are Jacques Tourneur’s exquisite 1957, Night of the Demon, based on M.R. James’s story, Casting the Runes, and Nigel Kneale’s 1958-59 Quatermass and the Pit (re-made as a film in 1967, released in the US as Five Million Years to Earth – “more powerful than a 1,000 H-bombs!”).

In Quatermass and the Pit, workmen disturb ancient skulls while digging out London’s (fictional) Hobbs Lane Tube Station, a site with a reputation for being haunted. The original owner of the skull is found to have been guarding a crashed spaceship nearby, manned by insect-aliens.

Unravelling the tale further, peering into the very minds of his freeze-dried psycho-bugs, Professor Quatermass sees that the insects were escaping a race war on Mars of their own making, caused by an ineradicable genetic psychosis… and they brought their psychosis with them when crash-landing on Earth a million years ago. What the previous haunting of Hobbs Lane only suggested now emerges full-blown, diabolical and dangerous to the public peace. The story is a pre-cog vision of Trump’s white-psychosis erupting across the public psyche in recent US elections, channelled by an inspired fever-dream of the program’s writers, who themselves had only just emerged from a war against fascism and were sinking into a new (cold) war against a similarly deracinated, Communist East. Such connections are only strengthened when you find out that the scriptwriter explicitly based the Martian race war on the Notting Hill race riots of 1958 2

hot, freshly steamed jam on the road

Night of the Demon stages a showdown between the (arrogant and over-confident) ascendant powers of reason and science on the one hand, and a folk legacy of superstitious irrationalism on the other, its hankering after ‘primitive’, older gods. We see a scientist, Professor Harrington, begging a certain Dr Julian Karswell to cancel the curse he placed upon him in return for ending his investigation into Karswell’s rural Satanic cult. Karswell seems interested, but soon enough the Professor turns up as hot, freshly steamed jam on the road, mangled and fried by an unfortunate collapsing power line. Another scientist, a young Dr Holden, flies in to solve the mystery of his death alongside Professor Harrington’s conveniently attractive niece.

They begin with a local farm worker, Rand Hobart, a suspect in the killing who has not yet been interviewed as he has fallen into a catatonic trance that leaves him seemingly incommunicable, lost. Under hypnosis (science), he relives a recent satanic ritual undertaken with his extended family, led by the matriarch, their mother, in which a fire demon has been summoned. Hobart saw the demon and collapsed into a terror, only subdued by releasing him back into his coma. The demon is afoot.

It seems Karswell cursed Harrington with a Runic inscription marked on a parchment he slipped him. He does the same now to Holden. Holden, though, discovers through his library research (into ‘ancient manuscripts’, of course) a means of controlling the magic: the secret is to get the sender, Karswell, to accept the parchment back in return, thus redirecting the curse back on themselves. It’s just that the parchment must be freely accepted, not forced. Holden achieves this through a clever ploy on the train Karswell has jumped so as to escape, onto which Holden now chases him, succeeding at the last moment in passing the parchment back to Karswell.

The instant Karswell realises what has happened, the parchment leaps into life in his hands, jumping onto the tracks below. Karswell chases it as it blows down the line, scattering flame and sparks in its wake. In the final scenes, Karswell is consumed by the demon his spell summoned as it bears down on him (squeakily), enveloped in flames. A body is recovered the next morning from the rail tracks, burned and torn to bits, like Harrington before.

The result is one of history’s least convincing score draws: the beliefs of the irrational Rand Hobart and the irrationalist, Crowley-lite Julian Karswell, are confirmed down to the minutest detail by the meat-world intrusion of the demon, the butchering of its victims, scientists and magician alike, and the ability of Karswell and Co. to summon him in the first place – yet these cthonic powers are somehow turned against those who believe in them (Karswell and the Hobart clan) by those that do not (the scientist, Holden): science must incorporate such magical praxis in order to triumph over the magical. And despite Holden’s trawling through the British Library for controlling knowledge of the demon, this triumph is achieved not through high science, but through low peasant cunning (Holden craftily slips back the curse to Karswell tucked away among his matches.) Karswell dies by having his power rewired against him, flipping it into the service of reason; not through the appliance of modern science but by a medieval sleight of hand.

one of history’s least convincing score draws

Underlying our fascination with these stories is the conviction that buried with them in our memories lie the affective tools we need to navigate the weird and the eerie as they break on through today. By re-experiencing and appropriating a Bygone Eerie we attune our minds for our confrontation with the hyperobject of climate collapse, the resulting alienation and detachment of our lived worlds and the re-emergence of Titans, sprites, elves and the fascist swarm. It turns out that we’re considering a haunted past for clues to an entranced, spirited, future. Phil is dead set against spirits, though.

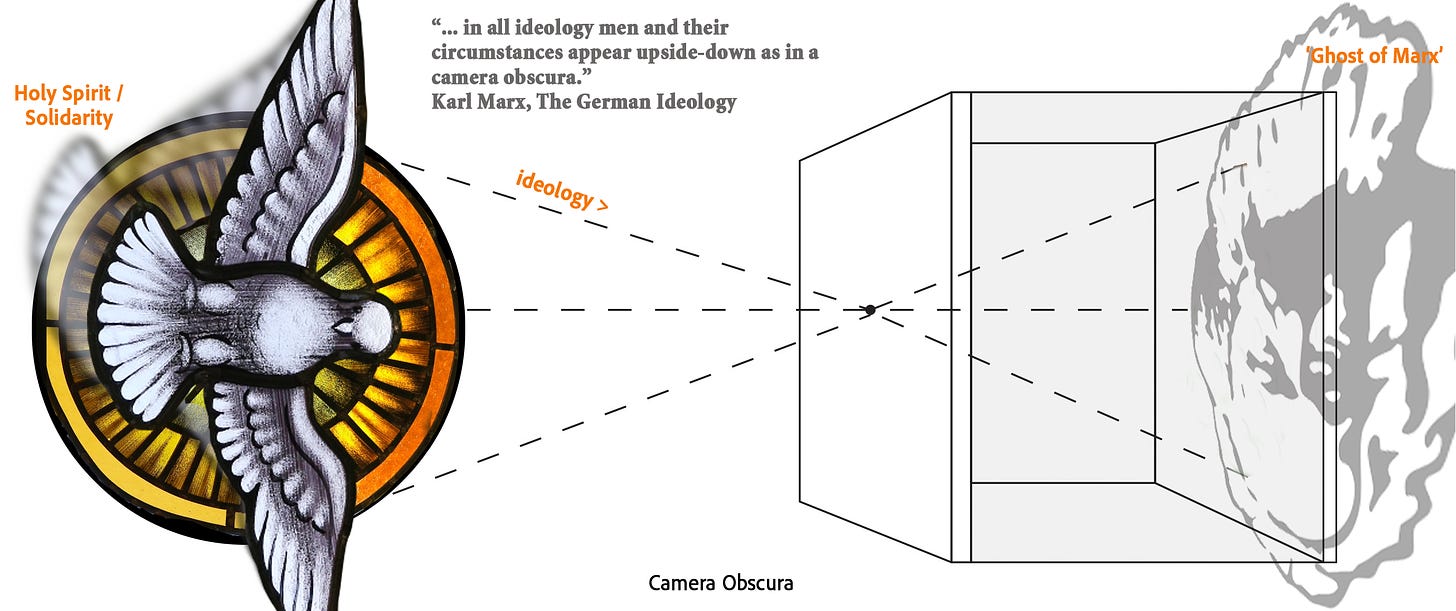

Such an impasse led Phil and I to discuss Mark Fisher’s idea of hauntology and the Ghost of Marx, as lifted from Jacques Derrida’s Spectres of Marx:3 why does the ground beneath and behind us seem haunted anyway? Whay are we fascinated?

The haunting in hauntology is primarily a haunting of us by Marx: the Ghost of Marx haunts the abandoned site of our desires, repository of our dreams and ambitions… but the future Communist utopia has been cancelled. There’s no future in England’s dreaming, but we persist in the absence of hope, the Ghost of Marx at our side. That’s their gruelling idea.

The Ghost of Marx haunts the abandoned camp of our desire

Perry Anderson triangulated modernism in the space between;4

PAST: the aesthetic, cultural and political legacy of the ancien régime, on the one hand, which clings on but must be overcome.

PRESENT: caught between Janus-faced principles pointing toward the past and future is the hugely transformative power of capitalism as it tramples superstition, prejudice and tradition underfoot in its relentless pursuit of profit and rationality, in its mode as Urizen’s ride.

FUTURE: at the other pole to the ancien regime is the socialist revolution; immanent, palpable, a future with its hand already tugging at our collar.

If we accept this triangulation as capturing the status quo ante, we can say that, for the (pro- and anti-) Occupy thinkers of a later era, the first difference is that the socialist revolution is now not only no longer either palpable or immanent, it is no longer even a transcendent ideal: the future has become merely unsystematic ‘history’, an event that didn’t happen, a memory of desire.

As agents of futurity there is nothing to tie us teleologically to the present, to give it meaning. The future falls away in advance of us, and Anderson’s triangulated modernism falls with it. Welcome to the postmodern.

As the further development of capitalism since Karl Marx and William Blake’s time has cleared the undergrowth, what remains still active from the past in our time from the accelerationist point of view – the equivalent of Anderson’s ancien régime – is the accumulated detritus of superstition that will soon fall away anyway if Capital is allowed to finish its job.

Now the future no longer holds, the past too is devalued since it is no longer the foundation of a future utopia. The duality of past and future falls into the hole of the present as it opens beneath us. Furthermore, this decapitation of the Left’s teleological framework leaves the forces of the present – the transformative, disillusioning power of capital – unconstrained. The fascistic accelerationism of Nick Land and the other ‘neo-reactionary’, ‘dark enlightenment;’ children of the CCRU (Cybernetic Culture Research Unit) submit to Capital because of its convenient power to sublate and transform the old. Down with the old, on with the new. For them, Capitalism is a self-moving apparatus set to destroy human folly, and they simply imagine that this must be the side where their bread is buttered, like rats forming a phalanx around the school bully.

The ‘spirit’-like qualities of Capital that rattled Marx are compacted by reactionary accelerationsim into diamond pellets of pure solipsistic will aimed at the brains of any remaining humanists, set to annihilate whatever stands in its way, inaugurating a post-human future since it is the human above all so plainly needs optimisation and ‘overcoming’ according to the tech bros and the new feudalists. Have you met their employees? Only fit for upgrading and further optimisation. Their meat must be optimised, as Timothy Morton put it, “in the service of transhumanist eternity and Google-eyed omniscience.”5

Capital appears to the new reactionaries as a vast AI system booting itself up, “guiding… history towards its own emergence.”6 Ultimately, the techno-fascists want it to break the back of the human once and for all, as Adorno understood of their predecessors. Such a perspective is possibly too stupid to be the real position of the clever-ish Nick Land: many have concluded that his real position remains unknown, buried under such carefully spun layers of indirection and bullshit. Still, he has enough followers. For now, let us focus instead on that wing of the post-CCRU crew not currently cowering so abjectly in the shadow of Deleuze.

Mark Fisher and friends, on the contrary, were not happy to throw themselves under the wheels of the capitalist Juggernaut this way, but sought instead to rescue the power of thought to negate Capital. They claimed to be sniffing out the historical resources to do this despite, by their reckoning, living in a situation characterised by the death of the future, shrouded in the ghosts of the past. Fisher’s problem was to bring this overstuffed turkey home, but he has trouble lifting it.

He starts by arguing that the (post-capitalist) future must now be conceived not as a simple negation of capitalism, but also as somehow part of its constructive legacy:

If it’s postcapitalism, it’s a victory and a victory that will come through capitalism. It’s not just opposed to capitalism – it is what will happen when capitalism has ended. It starts from where we are. It’s not some entirely separate space…7

Except, of course, that such continuity had always been part of the Marxist self-understanding and did not need resuscitation by accelerationists. Capitalism is not only an ideological, material and political barrier to socialism, it is also its essential precondition. Only the great dynamism of Capital could create the material abundance upon which Communism is predicated, not to mention its role (in much of Western Marxism) in eventually forming the proletariat as a ‘class in itself’, as Lukacs imagined so that the proletariat “can function as the identical subject-object of the social and historical processes of evolution”.8 Anyone who said otherwise was a dreamer. We ‘knew’ this.

In his Final Lectures, Fisher discusses a series of televisual moments that bear on his themes; the 1984 Apple ‘Big Brother’ Superbowl advert; a Levis advert from the same year in which their jeans, as objects of desire, are smuggled into Russia; and Louise Mensch’s 2010 TV appearance on Have I Got News For You, in which she attacks the hypocrisy of Occupy protestors who are happy to use mobile phones and other products of capitalist development.

The dialectic of change and continuity: rebranding

Fisher’s analysis of the Apple-Levis moment is good, focussing (via Baudrillard) on how capitalism serves our desire back to us as products, but misses out on another class of adversion relevant to the discussion, namely rebranding. Campaigns such as that of British Petroleum in 2000, rebranding as ‘Beyond Petroleum’, or McAfee’s 2014 rebranding as Intel Security Group occurred because the old brand had to be binned as it was associated with crime and anti-social behaviour (British Petroleum’s oil spills, John McAfee’s underworld adventures.) But isn’t this also what Acid Communism is about – rebranding a failed product, namely the Marxisant Left?:

What are the advantages of the concept of post capitalism?… Why use the term ‘post capitalism’ rather than ‘communism’, ‘socialism’, et cetera? Well, first of all, it’s not tainted by association with past failed and depressive projects… The word ‘communism’ has lots of negative associations for people of my age and older.

Mark Fisher9

In rebranding Communism / Socialism this way, Fisher takes the core elements of those movements, labourism and workerism, as he understands them, and bastes them in Theory (Marcuse / Baudrillard / Butler / Land) to turn it into something ostensibly grander and longer-lasting – Acid Communism. But what theory? What workerism?

It is significant that Mark Fisher was at school during the 1984-85 miners’ strike, certainly the formative political experience for Phil and Andy, as discussed in the podcast. Fisher never experienced the transformation of the miners in the strike and had not been at Orgreave or with the flying pickets. This simultaneous distance from, and proximity to the last gasp of British labour on such a grand scale lends a tantalising aspect to Fisher’s relationship to labourism, which he accepts in its positive state almost out of gratitude for its still existing at all, while believing it has no future as such. He feels the lost potential of workerism, and, not knowing how to avail himself of its’ legacy, pins its badge on (the likes of) Corbyn and other ‘actually-existing’ socialists, to borrow a phrase from analysts of ‘actually existing socialism’ in Russia and points East.

the No of hatred, anger and frustration

Acid Communism thus logically collapses into ‘Acid Corbynism’, (admittedly, not directly of Fisher’s making, but merely its inspiration), in which we are asked to believe that the politics of the Communist Party’s British Road to Socialism, with its dreary electoralism and hostility to Europeans (because they would rob sovereign Parliament of the power to immanentise the eschaton by nationalising the top 200 monopolies) is somehow a prelude to worker’s autonomy. I won’t dwell on how shameful Corbynism and traditional Leftism turned out to be over Ukraine and Syria, but that was to be expected.

Just as bad is Fisher’s 2013 essay, ‘Exiting the Vampire Castle’,10 where he slumps into a parody of donkey-jacket-and-warm-beer workerism defending ‘class’ from ‘identity politics’: “it is imperative to reject identitarianism, and to recognise that there are no identities… The bourgeois-identitarian left knows how to propagate guilt and conduct a witch hunt, but it doesn’t know how to make converts.”11 Bless. All this is wrapped up in an appreciation of Russell Brand as the authentic voice of the working class. I guess we can laugh about it now, but it is nevertheless easy to imagine Radek giving a version of this speech to a meeting of the Soviet Writers Union in 1934.

Actually, if you lived in Liverpool in the mid-1980s, as I did, you could have heard members of the Trotskyist Militant group say the same things as Fisher, in much the same tone, as when they controlled the local Labour Party and ran down Labour Party women’s groups and black sections precisely because they believed that the assertion of such ‘sectional’ identities ‘divided the working class’ and should be resisted. They were known then, at least on my bit of the far left, as crude, pseudo-Marxists: it is astonishing thirty years later to see the children of Deleuze and Guattari repeat this privileged yapping, doling it out as if it were news. No wonder that generation had trouble adapting to #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, given the collapse of their thought into such Maoist slogans and soundbites; no wonder Nina Power became an advisor to populist Conservatives, keen on young men finding themselves at the gym.

Ultimately, this wing of left accelerationism submerged itself in variants of traditional labourism, while the right accelerationist sought unio mystica with Capital itself, conceived as a terrifying, all-consuming big Other ding-an-sich to swallow them all.

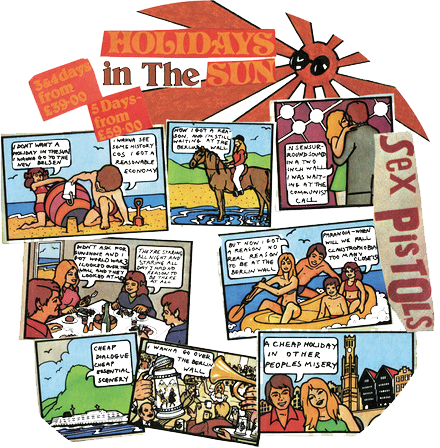

Punk’s labour of the negative abandoned

Not far beneath Lyotard's desire-drunk ‘yes', lies the No of hatred, anger and frustration: no satisfaction, no fun, no future. These are the resources of negativity that I believe the left must make contact with again.

Mark Fisher12

One final peculiarity of Fisher and his cohort is their vacillating relationship to negation and the power of the negative. Fisher says it is part of his brief to rescue, or restore the power of the negative, which had fallen into disrepute (see the quote above, aimed perhaps at Benjamin Noys, who wrote a then-influential book on ‘the persistence of the nagative’.)13 The Ghost of Marx is arguably a mannequin on which to pin this continuing labour of the negative, though it can never animate it. And yet, in their treatment of the counterculture of the 70s and 80s, none of them can get to grips with the negative power of punk that made the walls of the Real melt and fade.

In place of the Holy Spirit cranked into the nation’s veins by Bill Grundy after the evening news, we are offered the comfortingly productive fodderstompf of post-punk. While it isn’t hard to draw lines of continuity between punk and The Pop Group, or punk and The Fall (both punk groups anyway) post-punk, inasmuch as it had an identity at all, was how punk was reabsorbed into mainstream rock culture by recasting it as a sort of street prog-minimalism. K-Punk fellow-traveller, David Stubbs, thinks punk is “often crudely caricatured as a roar of working-class discontent, a political protest, whereas in fact… It and Thatcherism were arguably two sides of the same coin”.14 Meh.

In Post-Punk Then and Now, a collection by Gavin Butt, Kodwo Eshun, Mark Fisher, – “contemporary reflections by those who shaped avant-garde and contestatory culture in the UK, US, Brazil and Poland in the 1970s and 1980s” – sincere people struggle, as you would, to extract the Zeitgeist from Green Gartside’s Eurocommunist musings on Gramsci and his original ‘Scritti Politti’. Simon Reynolds’ Totally Wired: Postpunk Interviews and Overviews will breathlessly tell you the chart position of every post-punk record that charted. None of them see the power of the negative in punk, just as they don’t get the existence of the negative in workerism.

Punk, then, is seen by them, at best, as a sort of indisciplined ultra-leftism, insufficiently harnessed to any productive program of activity with which to get properly on board. Just as the PCF stewarded their demonstrations in 1968 to keep revolutionary students away from impressionable workers, and as A.L. Morton retroactively decided that the Ranters would have caused trouble on marches, the Occupy generation patrol the borders of the counterculture to swat away any sign of punk negativity that might rattle everyone’s concentration. Unfortunately for them, punk negativity is one of the prime bolt-holes of the Holy Spirit, where it hides from bourgeois productivism.

Not being productive, punk couldn’t be managed (Talcy Malcy notwithstanding), and here lies the problem for the post-punk busy-bees of the Acid Communist disco. Its negative quality means punk resists the telos they harness things to, that arc of history once grounded in a future communist utopia, now forever unmoored. But what if you cut loose the project of communism from this telos?

Such thoughts led Phil and Andy in the podcast to talk about their experiences of visiting picket lines. Both had been activists in the UK Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the 1980s; Phil in Bristol, Andy in York and Liverpool. Phil explained that what hauntology meant in practice was that you still visited the picket line, but now without hope of the strike being connected anyhow to any final showdown with capitalism, or what used to be called a ‘grand narrative’. Without the teleology strapping it to the future, the present is haunted by its absence. What rightfully belongs in that space if it is no longer Marx?

In conclusion, Andy wondered if perhaps the Ghost of Marx was just an ideological inversion of the real state of affairs, like the light reflected over hot tarmac on a sunny day, much as Marx said in The German Ideology, that “in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura.”15 Maybe Marx’s Ghost is an inverted echo of the missing Holy Ghost: maybe we should forget about ‘building the party’, and our intellectuals give up trying to find the groove that would finally animate dead ideas. Where telos was, let there be solidarity.

What if, instead of turning up on the picket line or refugee camp with a plan, instead we opened ourselves to the future simply by taking a chance on compassion and solidarity. If the Western left had looked at the people of Syria as needing solidarity rather than tactical advice over the last 15 years, maybe their name would not now be dirt in Syrian activist circles.

The picture that emerged from our discussion is of the left response to the dark enlightenment capitulating to traditional labourism (Acid Corbynism) and crude workerist politics (the Vampire Castle) alike. Maybe we should not be mourning the death of Marx but celebrating the power of love and solidarity to take us beyond the ‘end of the future’ and this endless, miserable haunting.

Podcast Discussion Summary

Phil and Andy explored themes from Phil's book Albion's Eco-Eerie, and delving into political ideologies and philosophical concepts. They shared personal experiences and perspectives on topics such as materialism, the supernatural, and environmental issues. The conversation touched on various subjects including the appeal of mushrooms, the changing nature of landscapes, and the need for new ways of understanding and relating to the world in light of ecological challenges.

Exploring 'Occupy Left' and 'Hauntology

Andy and Phil discussed the evolution of political ideologies, particularly focusing on the 'Occupy Left' and the concept of 'Hauntology'. Andy, who has a background in activism and Marxism, expressed his disappointment with Mark Fisher's 'Acid Communism', viewing it as a rebranding of traditional Marxist ideas. He suggested that the 'Occupy Left' and 'Hauntology' might be connected to the ecological disaster and the concept of 'hyperobjects'. Andy expressed his desire to understand the contributions of these ideologies to the current ontology and the sense of the eerie. Phil agreed to help Andy explore these ideas further.

Phil's Rugby and Philosophical Approach

Andy was feeling unwell due to an abscess in his tooth and high blood pressure, which affected his ability to concentrate. Phil expressed his interest in ideas and theories, but admitted he lacked the rigor and tradition of a philosopher. He described his approach to understanding history and the world as a materialist, bouncing off what he sees happening in the world. Andy suggested that Phil could explain his use of ideas and how they reflect back on them, leading to a discussion about Phil's book.

Exploring Socialist Roots and Hauntology

Phil and Andy discussed their shared background in left-wing politics, specifically the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the UK. Phil recounted his experiences as an activist in the 1980s, while Andy shared his involvement in the miners' strike and his expulsion from the SWP on philosophical grounds. They both expressed their disillusionment with the failure of the socialist project and the collapse of the working class movement. The conversation then shifted to the concept of ‘hauntology’ as discussed by Derrida, with Phil explaining how it relates to the spectral quality of existence within the current capitalist development. Andy expressed his interest in understanding this concept further.

Determinism, Solidarity, and the Eco Eerie

Phil and Andy discussed the concept of determinism and its relation to the idea of change. Phil argued that despite the philosophical refutation of determinism, there was a lingering structure of feeling that suggested otherwise. Andy suggested that the idea of solidarity could be a more radical approach, rather than focusing on building a party or defeating the US Empire. Phil shifted the conversation to his book on the Eco-Eerie, which Andy found enjoyable and thought-provoking. Phil acknowledged the difference in their trajectories, attributing it to their differing perspectives on William Blake's ideas.

Materialism, Supernaturalism, and Environmental Crisis

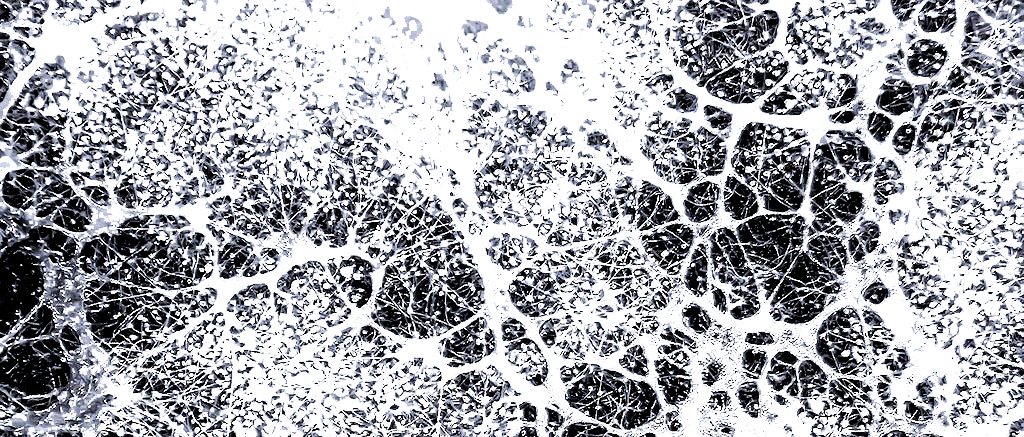

Phil and Andy discussed their differing perspectives on materialism and the supernatural. Phil expressed scepticism towards the idea of a spiritual realm, instead focusing on the material world, particularly concerning the environmental catastrophe caused by mining and deforestation. He shared his experiences visiting spoil heaps and exploring the post-industrial landscape. Andy, on the other hand, drew parallels between the supernatural and the current climate crisis, suggesting that the old gods are rising again. The conversation also touched on the idea of the eerie and the weird, with Phil suggesting that the fragmentation of our world is reflected in the breaking up of previously solid concepts. Andy proposed that this could be why people are drawn to the idea of the ‘Wood Wide Web’ and the interconnectedness of fungi.

Mushrooms and Hyperobjects in Media

Phil and Andy discuss the appeal of mushrooms and their connection to the ‘weird’ and ‘eerie’ as described by philosophers like Eugene Thacker. They relate this to the idea of hyperobjects like climate change, which have an unsettling presence or absence. Phil suggests that people are drawn to mushrooms and monster movies as a way to confront and contemplate these vast, chaotic forces in a safe, meditative way. He argues for attending to and supporting these ‘material monsters’ without necessarily recruiting others to a specific ideology. The conversation touches on themes of solidarity, subjectivity, and finding meaning in the face of overwhelming phenomena.

Navigating the Strange and Eerie

Phil and Andy discussed the importance of learning to see and understand the strange and eerie aspects of life, drawing parallels with the collapse of the enlightenment and Marxism. Phil mentioned his book, which explores various artefacts and their connections to human transformation, including a zombie-like character in a movie. Andy agreed with Phil's perspective, noting the need for tools to navigate the current strange place. Phil emphasized that the book's content should be experienced firsthand, rather than just discussed.

Human Impact on Changing Landscapes

Phil and Andy discussed the changing nature of landscapes and the impact of human activity on the environment. Phil highlighted the contrast between the perceived superiority of city life and the reality of rural life, and the devastation caused by industrialized agriculture. Andy shared his experience of being scolded for not appreciating nature, and Phil agreed that these landscapes are abject and deeply traumatized. They also discussed the emergence of new species in urban environments, such as forget-me-nots, and the potential for a hybrid, mutant planet. Phil emphasized the need to accept and celebrate this change, and to adopt a quieter, less dominant role within the new planet.

Phil's Book and Eco-Horror Discussion

Andy and Phil discuss Phil's book and ideas relating to hyper-objects and eco-horror. Andy expresses his appreciation for Phil's insights and the performative aspects of the book. As their time runs out, Andy mentions needing to take painkillers for an abscess. He thanks Phil for the engaging discussion and invites him back to discuss his retelling of folk stories and their shared interest in state capitalism and Trotsky. Andy also promotes his website and podcast, encouraging listeners to subscribe and support it financially if possible.

Phil Smith

Phil Smith is a performance-maker, writer and researcher, specialising in work around performance, eco-gothic writing, site-specificity and mythogeographies. He is an Associate Professor at the University of Plymouth, and the author of Living In The Magical Mode (Triarchy Press, 2022). With visual artist Helen Billinghurst, he is one half of Crab & Bee, creating the 2018-2019 exhibition and performance project Plymouth Labyrinth and publishing ‘The Pattern’ (2020, Triarchy Press). With Tony Whitehead he is the co-author of the novel Bonelines (2020) and of the three neo-gothic novellas of The Silversnake Project (Triarchy Press, 2023). From the late 70s he worked as a freelance theatre writer (when not paying the rent with work as a porter, warehouse worker and grass cutter); since 1980 Phil has been company dramaturg for TNT Theatre (Munich); his and TNT’s artistic director Paul Stebbings’s book about the company, TNT: The New Theatre (Triarchy Press) was published in 2020. His latest book is Albion’s Eco-Eerie (Temporal Boundary Press), forthcoming is Crab & Bee’s Matter of Britain (with Helen Billinghurst) for Peakrill Press and a book on diagrammatical performances for Routledge.

Phil and I discovered in the course of the podcast that we’d both been members of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) at around the same time. Curiouser still, a week after the podcast was recorded we realised that we’d gone to the same school in Coventry within a couple of years of each other in the 70s. And here we are, on the trail of the weird and the eerie some half a century later.

The episode led to complaints from local community leaders: ‘Coloured Leaders Criticize BBC’, The Times. 24 December 1958. p4, thetimes.co.uk, accessed 2016-06-19.

Jacques Derrida, Peggy Kamuf (tr), Bernd Magnus & Stephen Cullenberg (intro), Spectres of Marx: The State of Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, New York & London: Routledge Classics, 1994. Originally published in France as Spectres de Marx, Editions Galileé, 1993.

“The hypothesis I will briefly suggest here is that we should look rather for a conjunctural explanation of the set of aesthetic practices and doctrines subsequently grouped together as ‘modernist’. Such an explanation would involve the intersection of different historical temporalities, to compose a typically overdetermined configuration. What were these temporalities? In my view, ‘modernism’ can best be understood as a cultural field of force triangulated by three decisive coordinates. The first of these is something Berman perhaps hints at in one passage, but situates too far back in time, failing to capture it with sufficient precision. This was the codification of a highly formalized academicism in the visual and other arts, which itself was institutionalized within official regimes of states and society still massively pervaded, often dominated, by aristocratic or landowning classes: classes in one sense economically ‘superseded’, no doubt, but in others still setting the political and cultural tone in country after country of pre-First World War Europe. The connexions between these two phenomena are graphically sketched out in Arno Mayer’s recent and fundamental work The Persistence of the Old Regime, whose central theme is the extent to which European society down to 1914 was still dominated by agrarian or aristocratic (the two were not necessarily identical, as the case of France makes clear) ruling classes, in economies in which modern heavy industry still constituted a surprisingly small sector of the labour force or pattern of output. The second coordinate is then a logical complement of the first: that is, the still incipient, hence essentially novel, emergence within these societies of the key technologies or inventions of the second industrial revolution: telephone, radio, automobile, aircraft and so on. Mass consumption industries based on the new technologies had not yet been implanted anywhere in Europe, where clothing, food and furniture remained overwhelmingly the largest final-goods sectors in employment and turnover down to 1914.

The third coordinate of the modernist conjuncture, I would argue, was the imaginative proximity of social revolution. The extent of hope or apprehension that the prospect of such revolution aroused varied widely: but over most of Europe, it was ‘in the air’ during the Belle Epoque itself. The reason, again, is straightforward enough: forms of dynastic *ancien régime*, as Mayer calls them, did persist—imperial monarchies in Russia, Germany and Austria, a precarious royal order in Italy; even in Britain, the United Kingdom was threatened with regional disintegration and civil war in the years before the First World War. In no European state was bourgeois democracy completed as a form, or the labour movement integrated or coopted as a force. The possible revolutionary outcomes of a downfall of the old order were thus still profoundly ambiguous. Would a new order be more unalloyedly and radically capitalist, or would it be socialist? The Russian Revolution of 1905–1907—which focused the attention of all Europe—was emblematic of this ambiguity, an upheaval at once and inseparably bourgeois and proletarian.”

Perry Anderson, ‘Modernity and Revolution’, contribution to the Conference on Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in July, 1983, New Left Review I/144 Mar/Apr 1984, newleftreview.org, accessed 2024-10-30.

Timothy Morton, ‘Hideous Gnosis Unbound: The Apotheosis of Speculative Realism’, Bring Me My Bow of Burning Gold, Substack, timothymorton.substack.com, accessed 2024-12-21.

Mark Fisher, Matt Colquhoun (ed, intro), Post Capitalist Desire: The Final Lectures, London: Repeater Books, 2021. Final lecture series at Goldsmiths, p40.

Mark Fisher (2021), p50.

Georg Lukacs, Rodney Livingstone (trans), ‘Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat’ (1923), in History & Class Consciousness: III The Standpoint of the Proletariat, London: Merlin Press, 1967, Marxists.org, marxists.org, accessed 2024-12-21.

Ibid.

Mark Fisher, ‘Exiting the Vampire Castle’, OpenDemocracy, opendemocracy.net, 2013-11-24, accessed, 2024-11-17.

Ibid.

Mark Fisher, ‘Terminator Versus Avatar’, in #Accelerate: The Accelerationist Reader, Robin Mackay, Armen Avanessian (eds), Falmouth and Berlin: Urbanomic, 2014, pp339-340, quoted in Matt Colquhoun, ‘Introduction’, in Mark Fisher. (2021), pp19-20.

Benjamin Noys, Persistence of the Negative: A Critique of Contemporary Continental Theory, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010.

David Stubbs, Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Don’t Get Stockhausen, London: Zero Books, 2010, pp83-4.

Karl Marx, The German Ideology: Critique of Modern German Philosophy According to Its Representatives Feuerbach, B. Bauer and Stirner, Ch 1. ‘Feuerbach: Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlooks’, 1846, Tim Delaney, Bob Schwartz, Brian Baggins (transcription), Marx / Engels Internet Archive, marxists.org, accessed 2024-12-20.

Share this post