Blake's Annihilation by the Eye of Ra: On Snakes, Seraphim and the Solar YHWH

Some thoughts on what Blake meant by saying that when he looked at the sun he saw a choir of angels singing ‘Holy, Holy, Holy’, and how it relates to his depiction of a personal apocalypse.

They and only they can acquire the philosophic imagination, the sacred power of self intuition, who within themselves can interpret and understand the symbol, that the wings of the air-sylph are forming within the skin of the caterpillar; those only, who feel in their own spirits the same instinct, which impels the chrysalis of the horn fly to leave room in its involucrum for antennae yet to come. They know and feel, that the potential works in them, even as the actual works on them.

Coleridge, Biographia Literaria1

In the year that king Uzziah died I saw also the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up, and his train filled the temple. Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly. And one cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the LORD of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory.

Isaiah 6:1-3

Corporeal Friends

We all have watershed moments, when we arrive at a realisation that changes the course of our lives. One such moment occurred to me in an argument with a friend in the back garden of my house over ten years ago. The two of us were involved in running a radical publishing company. We were discussing Blake, and I mentioned what Blake said about perception in his notes to the painting A Vision of the Last Judgement:

I assert for My self that I do not behold the Outward Creation & that to me it is hindrance & not Action it is as the Dirt upon my feet No part of Me. What it will be Questioned When the Sun rises do you not see a round disc of fire, somewhat like a guinea?’ Oh! no, no! I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host, crying Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty I question not my Corporeal or Vegetative Eye any more than I would Question a Window concerning a Sight I look thro it and not with it.

Blake, A Vision of the Last Judgement2

My friend, who has published on Blake, said he agreed, but that it was nevertheless “important to remember that the sun is fundamentally a process of nuclear fusion.” There was a pause of a few moments that felt longer, and in those moments I guessed we would soon have to part ways.3

We need to train that muscle which allows us to get a grip on the tenor of Blake’s thought, even where we can’t know the details

I couldn’t explain why, but I felt it just the same: anyone who responds like that has not grasped what Blake was saying—but what was Blake saying, and why should it matter? I realised there were two aspects of Blake’s idea at stake. First is the account he offers of imaginative perception, about how he sees through ‘the vegetative eye’ to something beyond. This was what my friend and I were perhaps disagreeing about. But beyond this there is the particular reality Blake refers to as his example—the sun as a choir of angels praising God. It was this image that pulled me in. What did Blake mean? From everything I knew about him I was convinced that he had seen these angels, and convinced they were real. But what was this reality?

My friend’s response heightened my interest in Blake’s image, and was the start of a deeper involvement with Blake’s work, which I began to study. I didn’t want to become a ‘Blake scholar’: I wanted to become Blakean. It doesn’t make sense when you say it out loud, but I felt I had to understand this idea of Blake’s because I already knew that understanding it would change my life. And I had the sense that this image of Blake’s I had in mind (angels in the sun) was only the flickering on the surface of a much deeper well of meaning that I wanted to jump into.

It is now ten years later. In the meantime, I don’t claim to have found a definitive answer to the questions I started with, but I have assembled what I believe are some of the main supports of a solution; those images and connotations that swarm in turn around Blake’s image of the sun as a choir of angels crying “Holy, Holy, Holy”.

This essay is not an attempt to outline ‘what Blake really meant’ by what he said, because Blake did not believe in that kind of pellucid transmission. To the consternation of his more modest friends, Blake would talk freely about his visions, but he understood that acquiring vision itself required imagination rather than literal knowledge he might either absorb or impart. He invites us, therefore, to read him instead ‘in the spirit’, without the use of crib sheets or mechanical props and wires. Nevertheless, many of the ideas I present below will have been understood as such by Blake. Some he may have been only partially aware of, perhaps as subsidiary aspects of another image he was more crucially engaged with. With other ideas there is an element of mythic objectivity, where ideas and images are implied by the structure of the mythic components involved, quite apart from whether they are understood by this or that person. Of some of these connections we can infer Blake’s views with some certainty, but we can never know the precise constellation of Blake’s thoughts. We need to exercise and train that mental muscle which allows us to get a grip on the tenor of Blake’s thought, even where we can’t know the details. To do that requires exercising the imagination. That having been said, let’s jump in the water.

Fourfold Vision and Newton’s Sleep

The first part of the problem is the easiest to deal with, superficially, at least. It concerns what Blake meant when he said that he saw “thro… and not with… the vegetative eye.” I don’t take this to mean that Blake was accident prone because he couldn’t see the furniture as he walked around a room. Instead, his first point is that our perceptions are determined by our nature and being, so that “A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees”4, and “As a man is So he Sees. As the Eye is formed such are its Powers.”5 Secondly, and crucially, the differences in our vision are not just matters of the detail of what we see—you notice one thing while I am captivated by another—but determine the type of reality we perceive.

Blake believed there was a hierarchy of perception. In modern terms we might say that the nature and quality of one’s perception depends on the extent of the individual’s psychic integration. In Blake’s terms, it depends on the extent of the reintegration of the Four Zoas.

Now I a fourfold vision see And a fourfold vision is given to me Tis fourfold in my supreme delight And three fold in soft Beulahs night And twofold Always. May God us keep From Single vision & Newtons sleep

Blake, Letter to Thomas Butts6

Blake’s own vision moved between these states. He valued ‘fourfold vision’ as the highest attainable state, and it was in this state that he saw the sun as he described it in A Vision of the Last Judgement. At the other extreme of perception is ‘single-vision and Newton’s sleep’, embodying the most reified and disenchanted sense of the space in which vision takes place, where that vision is of the mere arrangement of the physical objects within that space and the surfaces they present to us. Such vision is perfected in the linear perspective codified by Leon Battista Alberti in De pictura (1435), in which the world is constructed mathematically and logically entirely from the point of view of the individual. This is also the abstract geometric space required by the equations of Newton’s Principia to calculate the motions of the heavens and the trajectory of heavy artillery alike.

Fourfold vision is vision in the strongest sense, harnessing the full power of the esemplastic imagination.7 Blake himself regularly experienced such vision(s). They clearly involve a more rarefied and unusual state of being than Newton’s sleep—so we speak of singular ‘vision’ as our normal mode of perception, but of ‘visions’ in the plural when we refer to those moments in which a higher mode of vision is, perhaps fleetingly, achieved. These moments are rare and difficult to describe, but they are the goal of Blake’s prophetic art. So, while Blake imagines a hierarchy of perceptive states, we need to know more about Blake’s ultimate, imaginative vision in particular, in order to know what is at stake in this hierarchy. I believe that his image of the sun as a choir of angels is not merely a casual example of such expanded vision, mentioned only to illustrate the point about differing modes of perception, but is in fact the paradigmatic case of what Blake means by ‘vision’. So perhaps we can better understand this state of heightened vision by diving deeper into Blake’s image of the sun as a choir of angels. What was he thinking?

Chariot Mysticism and the Face of God

Rabbi Akiva said: Who is able to contemplate the seven palaces and behold the heaven of heavens and see the chambers of chambers and say “I saw the chamber of YH”?

Ma’aseh Merkava, Synopse 554

Blake’s image of the angels praising God in the midst of the blaze and heat of the sun rests on Isaiah’s account of his encounter with God, in which he “saw also the Lord sitting upon a throne / Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly / And one cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory” [Isaiah 6:1-3]. The chant ‘holy, holy, holy’ appears precisely twice in the Bible, here in Isaiah, and then again in Revelation when Isaiah’s vision is reprised. So Blake must have had these visions in mind. This chant, the trisagion, is a feature of worship in both Orthodox Christian and Jewish services. In Revelation too it is chanted in the presence of God and his six-winged seraphim. The author of Revelation describes the throne of God, surrounded by “four beasts… each of them six wings about him; and they were full of eyes within: and they rest not day and night, saying, Holy, holy, holy, Lord God Almighty.” [Revelation 4:8] Clearly, Blake in his vision of the sun is thinking of these meetings with God, but has used the sun in place of ‘the Lord sitting upon a throne’ in his image. Why does he shift the focus of the image this way?

Because of the prohibition on idolatry and images of God, it is rare in the Bible for anyone to be confronted with God, and rarer still for them to see his face. And yet here in Isaiah, and in parallel texts in Ekeziel and Revelation, and perhaps also in the story of Jacob’s Ladder, that is exactly what happens. Between around 200 BCE and 1100 CE there was a tradition within Judaism, called merkabah mysticism after the Hebrew for chariot, מרכבה, which focused on these moments when the prophets ascend to see God on his throne or, in the case of Ezekiel, his chariot. The tradition centres on a personal confrontation with God, like that imagined by gnostics in the early Christian church. Other key facets of this tradition worth noting here are that, first, according to merkabah tradition, even if it is not always explict in the original texts, not only does man see the face of God, but the face of God is that of a man. The second feature emphasised is the presence in this confrontation of God and man of winged beings whose role is central, even if it varies between different tellings. We will return to these points later.

apocalyptic vision is centred on the belief that a person directly, immediately and before death can experience the divine

I don’t know of any evidence that Blake was even aware of the merkabah tradition, let alone influenced by it, but I have no doubt that he focussed on the same aspects of this encounter with the divine as did the merkabahists. Isaiah and Ezekiel were always Blake’s ‘go to’ prophets. It is with them that he converses in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.8 He asks them “how they dared so roundly to assert that God spake to them”, to which Isaiah replies “I saw no God, nor heard any, in a finite organical perception; but my senses discover’d the infinite in everything, and as I was then perswaded. & remain confirm’d; that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God.”9 Blake’s later rejection of the “Vegetative Eye”10 is surely based on Isaiah’s demotion here of “finite organical perception”. Nevertheless, while saying that “the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God” is to strongly identify with Isaiah and Ezekiel in their role as prophets, it does not mean that Blake rejected that they had ‘seen God’ in their visions, though it changes our perception of what it is to ‘see God’. Isaiah’s faith in the authenticity of his own voice, its ‘honesty’, is predicated on the cleansing of his lips by the seraphim in his vision. No personal vision—no prophecy. Blake repeatedly returned to the key moments of merkabah literature—from Isaiah and Ezekiel—and from the related texts of the New Testament, principally Revelation, in both his writing and in his art. They were central to his understanding of apocalyptic vision: for early Jewish and Christian mystics the word most commonly used for divinely inspired dreams, visions and auditions, and prophetic inspiration, was apokalypsis, which means both apocalypse as we now think of it, but also revelation. Not only that but as April DeConick argues, this sense of apocalyptic vision is “centred on the belief that a person directly, immediately and before death can experience the divine”11 For Blake too, vision and apocalypse are similarly entwined, and it is this sense of vision that Blake uses in A Vision of the Last Judgement, where our story began. Once again we are on terrain shared by merkabah mysticism and personal gnosis.

The Angels

We need now to take a detour to look at the role of angels in our story. Centuries of Western art have accustomed us to an image of angels as pale, shaved, haloed human figures with dove-like wings, in white robes. But the Bible itself is as ambivalent as it is possible to be about the status, form, appearance and role of the angels, not only between texts, but often within a single text. For example, the story of how Abraham and Sarah were blessed with a child in old age begins with the visit of a group of angels;

And the Lord appeared unto him in the plains of Mamre: and he sat in the tent door in the heat of the day; And he lifted up his eyes and looked, and, lo, three men stood by him: and when he saw them, he ran to meet them from the tent door, and bowed himself toward the ground, And said, My Lord, if now I have found favour in thy sight, pass not away, I pray thee, from thy servant.

Genesis 18:1-3, KJB.

In a single, short paragraph, we are told that ‘the Lord’ appeared to Abraham, but that he somehow took the form of three individual, unremarkable men, while Abraham nevertheless immediately recognised and addressed these men in the singular as ‘my Lord’ (‘ădōnāy). The three messengers / angels are not described as such, and yet that is what they are, because they are messengers of God—the Hebrew mal’āk and Greek angelos are terms used specifically to describe messengers, albeit that the terms were later generalised to refer to all of God’s supernatural assistants, in any capacity. Yet these messengers to Abraham, although divine, appear entirely human: there is no mention of wings, flying, miraculous appearances and disappearances or any other godly accoutrements. The Rabbinic tradition identifies these angels at Mamre as Gabriel, Michael and Raphael. The Orthodox icon painter, Andrei Rublev, promotes them to become the Trinity of God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost. But all these identifications come later. The Bible itself is typically ambivalent. This ambivalence is expressed in the very grammar of the texts. When Abraham is about to sacrifice his son Isaac, at the command of God;

The angel of the Lord called unto him out of heaven, and said, Abraham, Abraham: and he said, Here am I. And he said, Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld… thine only son from me.

Genesis 22:11-12, KJB.

Here the subject of speech shifts, so that ‘the angel of the Lord’ appears to be both a messenger and yet somehow also God himself, saying that Isaac is saved because Abraham has shown that “thou hasn’t not withheld… thine only son from me.” The angel here is not so much a separate entity working at God’s behest, but rather an avatar of God, a mode of his appearing. This blending together of God and his hosts—the choirs of angels, spirits, daimons, etc.—is typical of the Bible, and reflects older, pre-monotheist habits of thought typical in the Near East—to the south in Egypt, to the North in Assyria and Babylon, and in the lands in between—in which gods commingle, and act as both aspects and avatars of one another. And it is in this polytheistic world that we will find the origins of the Bible’s angels.

Space, Wind and Wings

The angels of Genesis, the ones Abraham meets, have no wings. It was only in later times that they acquired them. There was a pattern in Assyria and Egypt alike, at either end of Canaan, of using winged beings to represent the winds, the cardinal directions and the totality of divine power. This identification of the wind and directions with the totality of power, and the choice of wings to represent this space or directionality, makes good sense, just as long as you think like an ancient Mesopotamian rather than a modern.12

The people of the ancient Near East did not share the modern, Newtonian ‘single-vision’ sense of space discussed earlier. They did not imagine space to be an abstract conceptual theatre, or a coordinate system. Rather, space for them was a material aspect of the universe, and you could feel it move in every gust of wind, even if they sometimes also believed that wind emerged from gaps in the firmament. Looked at this way, wind becomes concrete, ‘actually-existing space’. And what better way to represent this wind-space than wings, which both generate wind (space) when they beat, and also command and control the wind (space) in flight, becoming coextensive with it. With wind and space identified, and with wings viewed as the element’s primary technology, it would then make sense to depict wind demons as having four wings, representing the four cardinal directions.

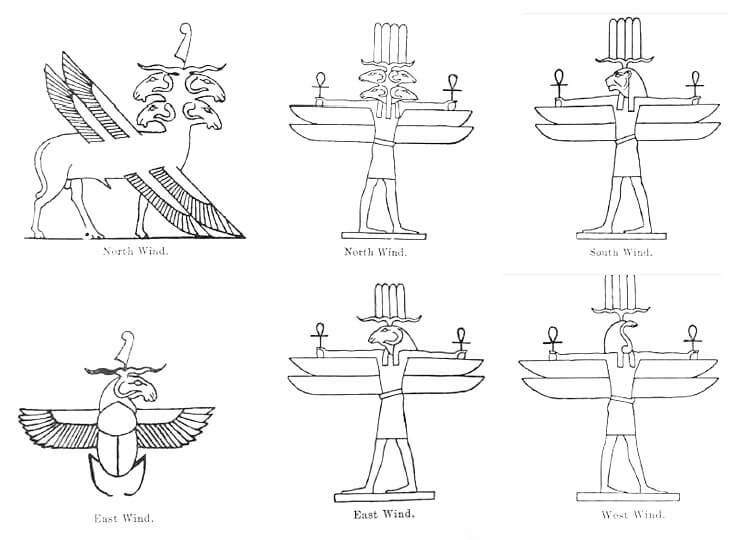

Thus the Egyptian gods of the winds all have four wings to represent the four directions. Not only that but they sometimes have four heads, and for the same reason. The North wind has four ram-heads, the South wind has a lion’s head, the East wind has the head of a ram, and sometimes the body of a scarab, while the West wind has the head of a snake.

Similarly, to the North of Canaan, the wind demons of Assyria had four wings. The Assyrian wind demon, Pazuzu, for example, is depicted as having four wings. And once again, wings are associated with the power of the wind and the directions of space. Pazuzu speaks of himself as “the son of Hanbu, King of the evil Lilû-Wind Demons, I ascend to the mighty mountains that quake. The winds, in whose midst I proceeded, were directed towards the West, I alone have broken their wings.”13 Like the Egyptian snake gods mentioned above, Pazuzu begins his career as an ‘evil’ spirit of destruction, a Lord of the underworld, brother to the demon Humbaba who is killed by the heroes of the Epic of Gilgamesh. However, in accordance with the (perfectly reasonable) mythological logic which says that if you want a spirit to protect and defend you, a fierce demon might be a good choice, Pazuzu soon begins to appear more systematically as a god of protection. Pazuzu, incidentally, is the demon that possesses Linda Blair’s character in the film The Exorcist, a role in which he is definitely cast in his earlier demonic, rather than his later protective, aspect.14

The Jews in Canaan and thereabouts at the turn of the first millenium BC incorporated aspects of the local religions into their own worship. Certainly they were familiar with four-winged daimons and spirits, as can be seen, for example, from the protection seals below, all from the area of Judea and Israel at that time.

The four-winged icons on the seals above15 have the heads of snakes, and are protective in intent—features which will make more sense once we have factored in the cult of the uraeus in ancient Egypt. But first let’s note that not only did the Judeans and Iraelites of the early Biblical age use the imagery of wind-demons in their seal, but the associated ideas made it into the Bible too. Scott Noegel notes that “the conceptual overlap between wings, winds, and the four corners of earth finds parallels in a number of biblical texts.”16 He offers the examples of lsaiah’s prophecy concerning the gathering of Judahites… “from the four ‘wings’ of the earth” [Isaiah, 11:12], and of Ezekiel’s warning that God’s wrath means that “The end has come upon the four ‘wings’ of the earth” [Ezekiel 7:2].17 In both cases, translations of the Bible uses terms such as ‘all four corners of the earth’ and ‘east, south, north and west’, but the original Hebrew uses the idiomatic ‘wings’ in line with the cosmology described above. Noegel concludes that “The ‘wings’ of the earth thus represent the ordinal directions from which the winds hail, and thus, they express a totality… they essentially mean ‘everywhere’… Indeed, the connection of ‘four-ness’ with the cardinal winds and a totality of power finds additional support in Daniel’s vision of a four-headed leopard with… ‘four wings of a bird’ [Daniel 7:6]”.18 More generally, “in Egypt and Mesopotamia, the creatures with four wings can represent the totality of power comprised of the major deities of the pantheon. In Israel, they represent the totality of Yahweh’s creative and life-sustaining power and his control over the cosmos.”19

Having established the widespread use in the ancient Near East of images of four-winged, often four-headed beings representing space/wind and the totality of divine power, let’s look at Ezekiel’s vision of the chariot, before God actually speaks to him, to see just how much of it rests on these connotations. Ezekiel’s four-winged beings are better known today as the cherubim.

Now it came to pass… as I was among the captives by the river of Chebar, that the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God… And I looked, and, behold, a whirlwind came out of the north, a great cloud, and a fire infolding itself, and a brightness was about it, and out of the midst thereof as the colour of amber, out of the midst of the fire. Also out of the midst thereof came the likeness of four living creatures. And this was their appearance; they had the likeness of a man. And every one had four faces, and every one had four wings… Their wings were joined one to another; they turned not when they went; they went every one straight forward. As for the likeness of their faces, they four had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and they four had the face of an ox on the left side; they four also had the face of an eagle… And they went every one straight forward: whither the spirit was to go, they went; and they turned not when they went… Now as I beheld the living creatures, behold one wheel upon the earth by the living creatures, with his four faces. The appearance of the wheels and their work was like unto the colour of a beryl: and they four had one likeness: and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel in the middle of a wheel.

Ezekiel 1:1-12, KJB.

In summary, we have our four ‘living creatures’, the cherubim, each with four wings (instead of the six winged seraphs of Isaiah) and four faces—of a man, a lion, an ox and an eagle. They surround the chariot and appear to move it. I take the expression that “they went every one straight forward… and they turned not when they went” to indicate some special type of motion involving a mastery of the space they moved in (like the wind itself). The new elements here are the four faces, the wheels and “the great cloud and fire… and a brightness”. The four ‘living beings’ (Greek: ζῷον, zōion) become Blake’s Four Zoas—Urizen and Urthona, Luvah and Tharmas—the basis of his analysis of the human condition, images of which appear throughout his work. But the major innovation concerns the ‘fire infolding itself’, and it is to this fire, and the related matter of ‘fiery angels’, that we now turn.

A Detour Through the Desert With Some Burning Snakes

The six-winged seraphim that surround God in Isaiah’s vision “are now generally conceived as winged serpents with certain human attributes”20 The word śārāp in the Bible is understood to be a derivative of the verb śārap—to ‘burn’, ‘incinerate’, ‘destroy’—and therefore the seraphim are ‘those that annihilate by burning’. At the same time, the root word is repeatedly associated in the Bible with snakes, or ‘fiery serpents’. In Numbers 21:6, YHWH sends “the fiery serpent” among the people; in Deuteronomy 8:15 the desert is described as the place of “fiery serpents”; in Isaiah 30:6 the desert is the abode of “the flying serpent” (śārāp mĕ’ôpēp). Taken together, what we have here is the idea of the seraphim as fiery, flying snakes that annihilate by burning.21

The seals with the four-winged flying snakes pictured above among the Protection Seals from Judah and Israel, were particularly prevalent in 8th century BCE in Judah, which is where and when Isaiah was writing. Regarding Isaiah’s vision of the seraphim, a few further points can be made. First, the seraphim are said to be positioned “standing above” Jahweh, which is exactly where the flying snake / uraei are found in friezes in Egyptian and Pheonician chapels of the time, in the area above the altar. And while Isaiah does not say how many seraphim are present, reading between the lines of the text it is generally assumed that there are two. The Book of Enoch argues that there were four seraphim, arguing as follows; “How many are the seraphim? Four, corresponding to the four winds of the world” [3 Enoch 26:8]. The argument fits well with what we know of the local cosmology concerning the wings, but I believe Isaiah was more likely to have two seraphim in mind, corresponding to the two protectors of the sun disc (see below).

More significantly, when Isaiah declares to God that he is unworthy of the prophetic role being thrust upon him, one of the seraphim takes a burning coal from the altar and “he laid it upon my mouth, and said, Lo, this hath touched thy lips; and thine iniquity is taken away, and thy sin purged.” [Isaiah 6:7]. This powerfully confirms the role of the seraphim as those who ‘annihilate by burning’, except that what is being annihilated is not the supplicant’s enemies, but their sins.

Othmar Keel has traced the use of uraeus iconography in Palestine from the Hyskos period to the end of the Iron Age, and this has led to “an emerging consensus that the Egyptian uraeus serpent is the original source of the seraphim motif.”22 The uraeus is the rearing cobra depicted on the Pharaoh’s crown, poised and ready to strike his enemies. The uraeus, therefore, is a protective deity, and a symbol of regal power and legitimacy. While uraeus symbolism is certainly an important aspect of the imagery of the seraphim, the identification with the cobra is not essential.

The ‘fiery snake’ imagery of both Egypt and Isreal derives ultimately from the animal life of the deserts of Africa and Arabia. From the various descriptions in the Bible of the attributes of the fiery snake, the most likely candidate—if we were to insist on there being only one—is the saw-scale viper or carpet viper (echis coloratus), though other candidates include the horned viper and the black desert cobra. The saw viper is of a reddish, ‘fiery’ colour, and has a lightning fast, flying strike and an especially painful, ‘burning’ bite, with which it injects a deadly venom that causes death by internal bleeding.23 The spitting cobra projects venom from its fangs by firing it into the eye of its victim over a distance of up to two meters. This venom can cause permanent blindness if not rapidly treated.

The uraeus has its origins in the ancient Egyptian snake goddess, Wadjet, tutelary deity of lower Egypt. Evidence of the worship of Wadjet goes to before the Old Kingdom of the third Millenium BC. Nekhmet was the similarly ancient protective goddess of upper Egypt, and appears depicted as a vulture alongside Wadjet in the full uraeus crown of the Pharaoh’s of a united Egypt. This ultimate protective role was transferred over to the protection of Ra himself, as the god of the sun and of the solar disc and Lord of all. Wadjet and Nekhmet are seen in Egyptian iconography flanking the winged solar disc. Their role is to protect Ra, shooting a consuming fire at his enemies that threaten to destabilise Ra in guiding the sun in its daily course. Egyptian theology even makes a distinction at points between Ra as such and the ‘Eye of Ra’, the solar disc, as an emanation of Wadjet, so that Wadjet becomes ‘the Eye of Ra’. Ultimately in Egyptian theology, all the other gods become aspects of Ra, and thus the winged sun disc becomes emblematic of ultimate divine sovereignty.

This winged solar disc, representing Ra, then becomes the symbol of secular lordship and regal power more generally. The use of the winged sun disc as a symbol of royal power appears not only in Egypt, but on Hebrew seals of the 8th century BCE associated with the royal house of the Kingdom of Judah. Specifically, it was used by King Hezekiah of Judah (c. 715-686 BCE).24 Immediately prior to that, it was in use by members of the court of Kings Ahaz and Uzziah of Judah.25 King Uzziah is estimated to have lived from 783-742 BCE, while Isaiah’s account of his vision begins, “In the year that king Uzziah died I saw also the Lord sitting upon a throne” [Isaiah 6:1]. I think it is reasonable to conclude that Isaiah, as the author of one of the canonical visions of YHWH as ‘the Lord’, would have been familiar with the images of the winged solar disc of Ra as representing such ultimate authority of Kings. And it is almost certain that he would have been familiar with the iconography of winged, fiery snakes —the seraphim—as uraeus snakes protecting the divine power. As this divinity is being experienced in its solar aspect, it is easy to understand how this would create an image of YHWH and the seraphim alike as burning, consuming forces.

The image of the solar disc, having originally been an image of Egyptian royal power, was projected onto the divine (Ra) and then spread across Judah and Israel in particular during the Hyskos period. On this basis it became part of Isaiah’s vision of his ‘Lord’. This secular image is explicitly projected onto the divine, onto JHWH, as can be seen not only in Isaiah but in the writings of the prophet Amos, writing in Judah only a few years before him.

Behold! The one who forms mountains the one who creates wind and the one who tells mankind what his thoughts are the one who makes the winged disc appear at down the one who treads upon the high places of the earth — YHWH, God of the hosts is his name.

Amos 4:1326

One aspect of the seraphim yet to be addressed is the fact that they have six wings, unlike the cherubim, who have only four, and other angels, who have only two, or none at all. The first thing to be said is that there were certainly other deities of the Near East with six wings. Such figures are found throughout the region on seals, statuary and other relics. There are coins from the 1st century BCE from Byblos, Phoenecia, showing the god El as a six-winged being: the coincidence of names (El) is striking, as these people were neighbours of Israel and Judah. But these are late images, and do not necessarily reflect the situation at the time of the prophets. However, a striking 10th century BCE Aramaean black basalt statue of a six-winged deity has been found at Tell Halaf, in modern northern Syria (see left). Similar six-winged figures can be traced back as far as the 3rd millenium BCE.27 With a lack of any other evidence, the obvious thing to do would be to take what we know about the correlation between wings and aspects of movement and dimensionality and see if that helps explain the different characteristics of angels (two wings), cherubim (four wings) and seraphim (six wings). Scott Noegel applies this logic and claims to find a good fit. Beings with two wings “share in common great speed, unidirectional movement, and a singular purpose,”28 whereas with four-winged cherubim, “their movement is both vertical and lateral in all the cardinal directions, but never unrestricted.” This is because they act like draft animals for YHWH, and thus the constriction of these great angels by the greater power of YHWH represents “a display of the totality and reach of divine power.”29 The six-winged seraphim, on the other hand, are unconstrained in all directions such that, unlike the cherubim, they can even ascend above YHWH, as Isaiah describes. The only constraint on the movement of the seraphim is that they are limited to movement within limnal space; “the seraphim function as extensions of the divine spirit and therefore, they remain outside the world of domestication.”30 They are purely transcendent—hence perhaps later claims that they are beings of ‘pure light’.

A Commodius Vicus of Recirculation Back to Blake, London and its Environs

My approach has been to take Blake’s original quote about seeing the sun as a body of angels praising God, and relate it to the texts of Isaiah, Revelation and Ezekiel, in which it is rooted. I’ve then unpacked the symbolism of those texts by reaching back to the myths and symbols of the ancient Near East at the time when the character of JHWH was being developed in Judah and Israel. The aim in doing this is to create a supersaturated solution of the combined visions of Isaiah, Ezekial and John, full of potential resonances. The next task is to try to crystallize out of this solution the particular image Blake had in mind when he appropriated the imagery of Isaiah and Ezekiel for his own purposes, just as they appropriated and repurposed the imagery of Pazuzu, Wadjet as the Eye of Ra, and the Egyptian wind gods. Bear in mind that Blake was not a scholar or philologist. He was deeply read in Bible literature, of course—the Bible itself, pseudepigrapha, apocrypha and commentary—but he did not read these works in order to make a comparative study of winged tutelary spirits of the ancient Near East. Instead, all of those influences would have incubated in his mind, to be put to work in his own system. It is a matter of working out which aspects of all this symbolism would, or would not have resonated with Blake, knowing what we know about his beliefs and demeanour.

We know that Blake looked to the imaginative art of the Near East as his model of any art worthy of the name. It is precisely to the models of Egypt, Israel and beyond that he is looking. He is also clear that he absorbed such influences through his own acts of imagination and vision. He tells us all this, for example, in the Descriptive Catalogue for his exhibition of 1809, when he describes his portraits of Lord Nelson and William Pitt as;

… compositions of a mythological cast, similar to those Apotheoses of Persian, Hindoo, and Egyptian Antiquity, which are still preserved on rude monuments, being copies from some stupendous originals now lost or perhaps buried till some happier age. The Artist having been taken in vision into the ancient republics, monarchies, and patriarchates of Asia, has seen those wonderful originals called in the Sacred Scriptures the Cherubim, which were sculptured and painted on walls of Temples, Towers, Cities, Palaces, and erected in the highly cultivated states of Egypt, Moab, Edom, Aram, among the Rivers of Paradise, being originals from which the Greeks and Hetrurians copied Hercules, Farnese, Venus of Medicis, Apollo Belvidere, and all the grand works of ancient art.

Blake, Descriptive Catalogue31

As to how Blake would have transfigured these mythological images of God and the cherubim in absorbing them, my first thought was that he was unlikely to have been much impressed by an image of God as an all-powerful ruler. He despised the way that such grovelling to power deformed people, and he excoriated the church for making that its modus operandi. So, whereas he would have shared Isaiah’s awed response, he would not have been cowed. In some senses, Isaiah was with Blake in this, at least part of the way: in his depiction of the seraphim it is made clear that neither they nor YHWH himself are a threat to Isaiah. Neither are the seraphim there to protect YHWH as Wadjet protects Ra—JHWH’s majesty is so effortlessly superior to anything else that he does not require protection. Instead, one of the seraphim’s concerns seems to be to protect themselves from JHWH’s radiant glory. This novel depiction of the role of the seraphim underlines JHWH’s special status, and is a major innovation in Isaiah’s use of the imagery of the fiery snake motif compared to how it was generally used throughout the region. So, in Isaiah’s vision, he is in awe of God’s majesty, but he is not mortally afraid in the way his Egyptian neighbours would have been if they’d idly stumbled across the deadly Wadjet and Nekhbet guarding Ra in his daily path across the sky. The seraphim do not attack Isaiah, instead they use the burning power of YHWH to purify Isaiah (with the coal from the altar—too hot even for the flaming seraph to handle, he uses tongs [Isaiah 6:6]). If the seraphim play a protective role, it is with regard to Isaiah, not YHWH.

The biggest shift of emphasis between Blake and Isaiah is that, whereas in Isaiah the symbolism of the solar JHWH is subtly incorporated (a radiant power, the burning coal), in Blake it is perfectly explicit-the angels themselves (seraphim or otherwise) form the hot cluster of the sun, presumably surrounding the deity, as in the renaissance images of choirs of angels surrounding God. This image eventually became a commonplace of religious art, for example in the painting A Vision of Angels, by Edward Burne-Jones, from 1870 (below). Having said that, the choirs of angels depicted in such works generally exist to illustrate the celestial hierarchy that is required to connect an ineffable deity to a palpable world. The idea of such a hierarchy was first worked out in detail by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite in the late 5th or early 6th century CE, and so cannot have been part of the vision of Isaiah or Ezekiel, over a millenium earlier. The assumption behind the celestial hierarchy is that God is a hidden and unknowable deus absconditus—an idea diametrically at odds with Blake’s (merkabah-like) belief in personal gnosis and the immanence of God (“God only Acts & Is, in existing beings or Men”).32 More than that, this hierarchy was used to justify secular religious authority at its lower levels, and as such would be alien and repellant to Blake’s entire cast of mind. So, while it is not unusual to see the angelic choir arranged in a solar formation around God in religious imagery, Blake will have had other reasons for imagining his angels clustered together in this solar formation. What were they?

Blake’s Annihilation By the Eye of Ra

One way of approaching the question of why Blake imagined the sun as a choir of angels—or, to put it another way, why he emphasised the inflammatory, solar aspect of the divine—is to ask what all this heat represented. What is this radiance or conflagration that is so fierce that even the seraphim have to protect themselves from it?

The ‘burning’ of the seraphim has often been thought of as a heightened ‘warmth’, expressing the ardour that the seraphim feel in the presence of God. It may also be thought of as a result of the seraphim’s ceaseless activity in praising God, this activity generating a kind of warming energy. In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas offers a number of explanations for the heat generated by the seraphim. He speaks of the heat as produced by an “excess of charity”.33 He also makes the comparison with the flames of a fire, in that the flame’s “movement which is upwards and continuous. This signifies that [the seraphim] are borne inflexibly towards God” (though this does not relate to the heat of the flame, only its motion).34 He makes a similar comparison regarding the ‘brightness’ of the flame; “the quality of clarity, or brightness; which signifies that these angels have in themselves an inextinguishable light, and that they also perfectly enlighten others.”35 In his Oration on the Dignity of Man (1487), Pico della Mirandola picks up on this idea of the enlightening, clarifying aspect of the flame, turning the seraphim into models for the new men of the Renaissance; “If we burn with love for the Creator only, his consuming fire will quickly transform us into the flaming likeness of the Seraphim.”36

Notwithstanding earlier criticism of the idea of celestial hierarchy (from Blake’s point of view), the notion of a vertically-arrayed hierarchy does suggest to Aquinas a further explanation of the heat of the seraphim which is at least somewhat compatible with Blake’s vision. Following Pseudo-Dionysius, Aquinas arugues that the heat of the seraphim is used to ‘draw up’ those members of the lower circles of the hierarchy toward God, such that “the action of these angels [is] exercised powerfully upon those who are subject to them, rousing them to a like fervor, and cleansing them wholly by their heat.”37 The element of hierarchy here makes the heat sound like a management tool for the training-up of subordinates—those lower down the divine chain of command—but it only takes a small twist to unshackle this notion from the legacy of the Aeropagite’s semi-feudal love of organisational charts. All you have to do is imagine that the heat is generated by the seraphim burning themselves up, rather than subordinate angels, etc., in self-annihilation as they approach God. There is no need for a hierarchy here, all that is needed is the notion that, as you approach God, you are annihilated and burned up, just as Isaiah’s iniquities were burned up by the burning coal on his lips. And self-annihilation was the stuff of Blake’s apocalypse, or at least “Annihilation of the Self-hood of Deceit and False Forgiveness”38

Removing the vertical hierarchy in this way leaves us with a model of the divine encounter which is not structured around the height of the altar and movement below and above it, but instead has the divine as the centre of a sphere, to which everything is drawn in every direction. This is the vision of the celestial choir in Dante’s Paradiso, imagined as a white rose;

In fashion, as a snow-white rose, lay then Before my view the saintly multitude, Which in his own blood Christ espous’d. Meanwhile That other host, that soar aloft to gaze And celebrate his glory, whom they love, Hover’d around; and, like a troop of bees, Amid the vernal sweets alighting now, Now, clustering, where their fragrant labour glows, Flew downward to the mighty flow’r, or rose From the redundant petals, streaming back Unto the steadfast dwelling of their joy. Faces had they of flame, and wings of gold; The rest was whiter than the driven snow. And as they flitted down into the flower, From range to range, fanning their plumy loins.

Dante, Divine Comedy: Paradiso XXXI39

This idea of the seraphim burning in self-annihilation is reflected in Kabbalah, in which the seraphim are part of the world of Beri’ah, the second level of manifestation, the level of divine understanding, and the ‘realm of the throne’, in which the seraphim rise and fall like sparks dancing over a fire. A Hekhalot commentary on Isaiah’s vision (part of the Merkabah tradition) gives a sense of how this process of purification and self-annihilation might be imagined:

The Holy Living Creatures do strengthen and hallow and purify themselves, and each one has bound upon its head a thousand thousands of thousands of crowns of luminaries of divers sorts, and they are clothed in clothing of fire and wrapped in a garment of flame and cover their faces with lightning. And the Holy One, Blessed be He, uncovers His face. And why do the Holy Living Creatures and the Ophanim of majesty and the Cherubim of splendor hallow and purify and clothe and wrap and adorn themselves yet more? Because the Merkabah is above them and the throne of glory upon their heads and the Shekhinah over them and rivers of fire pass between them. Accordingly do they strengthen themselves and make themselves splendid and purify themselves in fire seventy times and do all of them stand in cleanliness and holiness and sing songs and hymns, praise and rejoicing and applause, with one voice, with one utterance, with one mind, and with one melody.40

Here I think we have all of the elements of Blake’s vision of a confrontation with the divine: the ‘holy living creatures’ (the Zoas or Tetramprphs, formerly the seraphim and cherubim, and before that, fiery snakes protecting the sun disc) perpetually extinguish and annihilate themselves in acts of purification as they stand before God, face to face, and recognise themselves. To describe this as being annihilated by the Eye of Ra is not to say that Blake worshipped a solar deity, but the violence of self-annihilation in the confrontation with God is nevertheless a legacy of Wadjet’s fiery attack, except this time the fire generated is strictly one of self-immolation. To experience this particular apokalypsis is as good as four-fold vision gets. This, I believe, is something like what Blake had in mind in talking of the sun as a choir of angels exalting God.

Samuel Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, Vol. 1, pp241-2.

“Every Time less than a pulsation of the artery / Is equal in its period & value to Six Thousand Years. / For in this Period the Poets Work is Done”, Blake, Milton I 28/30:52-29/31:2, Erdman p126-7. For what its worth, I wouldn’t break up a friendship with someone based on their mistaken understanding of Blake. There were much more pressing issues involved. But this disagreement was much more than a straw in the wind.

“‘Esemplastic’ is a qualitative adjective which… Samuel Taylor Coleridge claimed to have invented. Despite its etymology from the Ancient Greek word πλάσσω for ‘to shape’, the term was modelled on Schelling’s philosophical term Ineinsbildung–the interweaving of opposites–and implies the process of an object being moulded into unity. The first recorded use of the word is in 1817 by Coleridge in his work, Biographia Literaria, in describing the esemplastic—the unifying—power of the imagination.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org.

Blake, ibid.

April DeConick, ‘What is Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism?’, quoted in Christopher Rowland, ‘Wheels within Wheels’: William Blake and the Ezekiel’s Merkabah in Text and Image, Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2007, p12.

For a discussion of these ideas and their development in the Near East, see Scott B Noegel, ‘On the Wings of the Winds: Towards an Understanding of Winged Mischwesen in the Ancient Near East’, Kaskal: Rivista di storia, ambienti e culture del Vicino Oriente Antico, Vol 14 2017, Florence: Logisma, 2017.

Scott B Noegel, p17.

See wikipedia.org, accessed 2021-03-11.

Benjamin Sass, ‘The Pre-Exilic Seals: Iconism vs. Aniconism,’ in Studies in the Iconography of Northwest Semitic Inscribed Seals; Proceedings from a Symposium Held in Fribourg on April 17-20, 1991, ed. B. Sass and C. Uehlinger; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993, fig. 79., online in Taylor Gray, The Seraphim Through the Eyes of Isaiah, Transpositions < www.transpositions.co.uk/seraphim-eyes-isaiah > accessed 2021-03-11.

Scott Noegel, ibid, p19.

Scott Noegel, ibid.

Scott Noegel, ibid.

Scott Noegel, ibid, p39.

Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking and Pieter van der Horst (eds), The Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, Brill Academic Publishers / Erdman’s Publishing Company, 1999, p742.

Curiously, when the Israelites complain to Moses about the fiery snakes that lethally attack them, God commands Moses to make the Nehushtan—a bronze snake on a cross. The Israelites who pray to the serpent on the cross are saved from the lethal bite of the desert serpents. Later prophets destroyed the Nehushtan as the worship of it had become idolatrous. Later still, in the Christian era, the snake on the cross was seen as a precursor of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. This identification in turn no doubt encouraged those gnostics who venerated the serpent as the bringer of wisdom to mankind. There is clearly a parallel here with the Greek god, Asclepius, who carried a rod with a serpent wreathed around it, which he used to heal sickness, and even to resurrect the dead.

Noegel, ibid.

See Wikipedia, wikipedia.org, accessed 2021-03-11.

Robert Deutsch, ‘Lasting Impressions: New bullae reveal Egyptian-style emblems on Judah’s royal seals’ (2002). Biblical Archaeology Review 28:4, pp 42–51, archaeological-center.com, accessed 2021-03-11.

Daniel Sarlo, ‘Winged Scarab Imagery in Judah: Yahweh as Khepri’ (2014). Eastern Great Lakes Biblical Society Annual Meeting, Erie, PA., academia.edu, accessed 2021-03-11.

My New Living Translation bible renders the relevant line as “He turns the light of dawn into darkness”, whereas KJB says that God “maketh the morning darkness”. It is John Witley who argues that the Hebrew involves the poetic invocation of the solar disc. See John Whitley, ‘עיפה in Amos 4:13: New Evidence for the Yahwistic Incorporation of Ancient Near Eastern Solar Imagery’, in Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 134, No. 1 (Spring 2015), pp. 127-138. Quoted in Scott Noegel, ibid, p22.

According to Scott Noegel, ibid, p28.

Scott Noegel, ibid, p33.

Scott Noegel, ibid, p34.

Scott Noegel, ibid, p36

Blake, A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures, Poetical and Historical Inventions, London, Berwick St: DN Shury, 1809. Erdman p 530-1

Aquinas, ibid.

Aquinas, ibid.

Pico della Mirandola, Oration on the Dignity of Man, history.mcc.edu, accessed 2021-03-11.

Aquinas, ibid.

Blake, Jerusalem 15.

Dante, The Divine Comedy: Paradise, tr. EF Cary, owleyes.org, accessed 2021-03-12.

Quoted in Gershom Scholem, Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism, and Talmudic Tradition (1960), Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Philadelphia: Maurice Jacobs Press, p29.