Brian Catling: Avoiding Blake: Defeated by a Flea in the Ear, a Talk to the Blake Society

Brian Catling gave a talk to the Blake Society about his relationship to Blake, running a meter over his work to detect splinters of Blakean influence.

Brian Catling gave a talk to the Blake Society about his relationship to Blake, running a meter over his work to detect splinters of Blakean influence, from his early confusion of Blake and Bunyan, to his use of Blake as a character in his novel, The Erstwhile.

Brian Catling’s Alchemical Sympathies: some notes

Brian Catling, Arena: Where Does it All Come From, Arena Documentary, BBC 4 / BBC iPlayer (2021). An Anti-Worlds Rook Films production. Directors: Geoff Cox and Andy Starke

Brian Catling, Avoiding Blake: Defeated by a Flea in the Ear, a talk to the Blake Society, 15th Dec 2021.

Brian Catling, A Court of Miracles: The Collected Poems of B. Catling, Etruscan Books, 2009.

If I have any taste

it is only because I have interested myself

in what was slain in the sun

Charles Olson, The Kingfishers III

The Teeth of the Hydra

Brian Catling is an artistic hydra: a performance artist and sculptor, he’s been a published poet for some decades. He’s also a painter. More recently, he’s written novels, which enterprising people are now turning into films. Just last November he was the subject of an admiring BBC Arena documentary.1

It’s tempting to think of Catling’s work chronologically, with the sculpture and performance at the core, and unfolding from there, through poetry in support of the sculpture and performance, onto the novels, with the films sprouting at the end. Having come to Catling the wrong way around, starting with his Vorrh trilogy of novels (after reading a boosting review by Alan Moore) this doesn’t work for me, and I watched the Arena video of his performances and listened to his talk, very much through the lens of the Vorrh.

His multitudinous activity and impact does not look like a man turning to different media in pursuit of a single end, harnessed to a single purpose. Catling doesn’t seem interested in establishing such a traditional footprint (“The word ‘career’ sticks in my throat.”2). His restless productivity proves instead that his urge to create refuses to be checked, spilling out like the guts of a particularly busy volcano, leaving traces everywhere. He can’t resist.

The Vorrh trilogy (The Vorrh, The Erstwhile, The Cloven) is set in and around the eponymous forest, rumoured to house the Garden of Eden at its heart. The forest is vast, and it deranges the mind and wipes the memory of anyone lingering too long. At its edge is the frontier town of Essenwald, transported wholesale from Europe. This Conradian setting is rounded out with storylines threading through England and Germany around the two world wars.

But if this is beginning to sound familiar, on the page it is anything but that. The frame of the story is packed with effervescing detail. Among the characters are monsters and golems, bakelite automatons, a cyclopian assassin (Ishmael), and the cherubim sent by God to guard the Tree of Knowledge in Eden, but abandoned by him once Adam and Eve were turned out. In the vastness of time, trapped at the heart of the forest and its ferocious forgetting, the angels mutate, evolve and develop their own plans, dispersing out of the forest and into the world.

Also appearing are a number of verifiable historical characters—or their twins and doppelgangers, variations on the ones we’re familiar with. Their familiarity helps centripetally to cohere the story, stitching it more firmly into the world we inhabit, bringing the fantastic closer to home: the Vorrh itself, the forest, first appeared in Raymond Rousell‘s Impressions of Africa, and Rousell appears here, along with Eadweard Muybridge, Louis Wain, William Blake and more. The invocation of Roussel, with his own, formal pyrotechnic engine of invention, is perhaps a clue to Catling’s method and intentions.

Catling’s speciality is not long-range planning of plot twists, and not even story development as such—leave that to the clients of creative writing courses. This has frustrated some reviewers, who insist on having a story that enforces the correct morals, but they are missing the point. The power of the writing is in its relentless poetic force. This imagination is arguably so powerfuly present that it overwhelms any attempt at linear narrative, toppling it under the weight of Catling’s invention. The effect is of an ongoing estrangement of everything, building a psychedelic hub in which both the imagined world that is conjured up, and the very story you are reading, are both similarly buckling and mutating, presenting new faces: the city of Essenwald is both a typical frontier outpost and an evocation of medieval Nurenberg, but turn any corner and you might be in a Morrocan street market or a remote Congolese brothel; turn the next corner and the geometry of space itself might be turned inside out, time starting to run backwards, or the ground under your feet heaving and sweating while the bugs beneath the paving slabs start speaking to you.

Promoted as a work of fantasy (the original publishers even tried passing it off as ‘steam-punk’), the Vorrh is a work of surrealist derangement. It provokes and astonishes with the force of its invention. The same can be said of Catling’s other novels (Munky, Hollow, Earwig, Only the Lowly). Hollow competes with the Vorrh in this regard. A friend who read it said she was rendered breathless by the power of individual scenes, one after another. In Hollow Catling has written a medieval Lovecraftian murder thriller that is his Name of the Rose to the Vorrh’s Gormenghast. The Vorrh and its Garden of Eden are replaced here by Das Kagel, a tower reaching into the sky, believed to be the collapsing ruins of the Tower of Babel. Its foundations consist of the decaying remains of a vast library of books, flattened in time by the weight of the tower into wafers of compressed dust and wood pulp. The books are being eaten by legions of creatures out of Hieronymous Bosch, who thereby become weirdly voluble and partly literate, speaking gibberish, infesting the countryside and engaging the population.

In the midst of all this, the oracle who protects the Monastery of the Eastern Gate, at the foot of the tower, dies, and the High Church send out a troupe of mercenaries to deliver a replacement oracle. Along the way, as the troupe face a chain of obstacles, the oracle lives by sucking the marrow from bones which are replenished only by the men whispering their darkest secrets into them—tales of wretched cruelty, lust, faithlessness and hypocrisy.

The Empathic Earwig

The Arena documentary and Catling’s talk to the Blake Society both focused on his sculptures, poetry, performance and painting, while I had been more familiar with the novels and the film Earwig. The separation of the two seems deliberate—the novels are published under the separate identity of B. Catling—not to obscure the authorship, I suppose, but to make the point that the sculptor and writer are perhaps up to different things. Surprisingly, Catling seems less sure of his written work (“that’s the area I’ve been most unsure about and where I expose myself the most.”3) Despite this, the works are all rooted in one perspective and project the same demeanour.

One element of continuity consists of Catling’s fascination with cyclops, who crop up a number of times in his work. In Ulysses, Joyce uses the figure of the cyclops to spotlight the narrowness of the Citizen, his limitations. The Citizen is a thug and a monomaniac. He fills the air with spite and malevolence. The cyclops, then, can be thought of lacking something essential to a full life, full awareness, and thus full humanity.

The eye, of course, is the organ par excellence of Romantic experience. Do we see the world as it is, or is it the case, as Blake argued, that “If Perceptive Organs vary: Objects of Perception seem to vary”,4 and “A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.”5 Blake prayed, “May God us keep / from single vision and Newton’s sleep”6 He imagined Newton’s reduced vision to be the lowest form of vision, vision reduced to the most mechanical means, lacking insight, empathy or connection. For both Blake and Joyce, the cyclops represents a bestial contraction of humanity.

But the cyclops can just as easily be thought of simply as having a different perspective. The result of Catling’s interrogation of objects in performance is often to generate an empathy for things, including his monsters. In his talk to the Blake Society, he speaks of his ‘methods’ and ‘techniques’, implying something like an objectivity of attitude, an analytical posture, but such techniques are geared towards rendering things alchemically toward us, the viewers, and his ritualistic approach is unfashionably tender.

He approaches the object in many ways, teasing it to extract sense and communicative action, to get a response from it—the work of the alchemist. I don’t know that the objects offer themselves up in the way he proposes to them, but we are nevertheless left with a sense of connection. The approach brings to mind the tale of the man who spends all night unsuccessfully calling for God to speak to him. In the morning he cries out one last time, “Why do you not make yourself known to me?” God replies: “Who do you think prompts you to keep calling?” The silence is made to speak.

Catling is fond of his monsters. His ideal is the one that befriends the blind girl in the 1931 film of the Frankenstein story. Not only is he fond of his monsters, he identifies with them: in ‘The Electric Influence’ (1971) he says “I wait for the cultured mob to burn me down”, just as the uncultured mob did to the monster in the film. He seals the point by dedicating the piece to James Whale, Colin Clive & Boris Karloff, the director and lead actors of the film.7

In Lucile Hadzihalilovic’s film of Catling’s Earwig, the war veteran, Scellinc (‘The Earwig’), is employed to care for the young girl, Maia, whose jaw has been re-engineered by the rubber-aproned Dr Rostlink so that her teeth have to be replaced each day with surrogates made from her own frozen saliva, which is collected by a strange device strapped permanently to the child’s face. Scellinc spies on Maia, using a glass to listen to her through her bedroom wall (“earwigging”). He also smashes a glass into the face of the barmaid, Céleste, disfiguring her. Events are set in motion that lead to a violent denouement in the grounds of the hotel /hospital whose image has recurred throughout.

As with The Vorrh, it is the mood and the details that are the substance. The effect on screen is of a ghastly silent horror film. The ritual of the teeth (which itself brings to mind Nazi atrocities through the image of the golden fillings taken from the victims of the gas chambers) has much in common with Catling’s performances in their shared impenetrability and opaqueness.

The relationships between Scellic, Maia, Céleste and the other characters have the same, formal, ritualised character. But once again we have no clues as to the meaning of the ritual. The tone evokes horror, but the seeming randomness of the character’s behaviour leaves everything shrouded in mystery, and the characters, being impenetrable, remain sympathetic even in the midst of the most dreadful events, because we barely understand their motivations. We do not know why they do what they do. Are they agents, or are they being shunted around by events much as we all often feel happens to ourselves.

Tying together the performances, novels, film, and even the poetry, is a coming together of imagination and formalism, ritualised attention to otherwise ineffable things: even of Catling’s poetry, Iain Sinclair says that it is “constructed with a certain formal stiffness, as it if it were a second language, have a good report of something overheard, but not fully understood.”8 Just as the alchemist had to repeat his experiments endlessly, Catling doggedly pursues his object with a form of enraptured attention: to the object, to the process, to the formula.

In any case, the autonomy of the object—and the integrity of the people, angels and monsters depicted—is thereby affirmed. This became especially clear in a scene from the short film he showed during his talk, where an aged man (his father?) speaks. The words were unintelligble, but the effect was to connect the viewer more deeply with the man, despite the opacity of the means offered to make the connection, the speech. The failure of mediation allows a sneak preview of an unmediated connection with things, with each other.

Brian Catling: Avoiding Blake: Defeated by a Flea in the Ear

A talk given to The Blake Society on 15th Dec 2021.

The text has been edited for clarity. Unless stated otherwise, all images & text ℗ & © Brian Catling 2021.

… immeasurably dense and confused and packed with a kind of fertile obscurity…

J H Prynne, on Charles Olson

I make many things and they self-fertilise. They cross over, they become ways of explaining the thing that went before, and sometimes the thing went before that that you’d forgotten. So that’s what I’m going to do. You’re going to see images of things I’ve made, or which have influenced me, and which are mysterious things in themselves.

I started by trying to find some logical understanding of how Blake influenced me, and how some of his ideas and images got into my work. And I realised I couldn’t do that. So I invented a kind of Blake Geiger counter and held it over my work, waiting for it to click, and thus it selected particular works. And I’m going to put them on screen and talk at them, about them, and around them. But they’ve been selected by the detector. And it could go wrong. This is the weirdest combination of things that I’ve ever put together, but it was all selected by the detector.

Here’s a badge I wore on my chest for many years. I went to a comprehensive school—a rather good one, an experimental comprehensive school in the Old Kent Road in South London. The Old Kent Road, of course, leads to Canterbury and was the Pilgrims route. The school wanted that to be part of what it was about. And this was my first confusion. I confused Bunyan with Blake at a very early age. The school hymn was To Be a Pilgrim but we all sang Jerusalem as well, so the two things became confused. This summons a picture that is so enormous it refuses to be separated. I’ll come back to this later on.

So I didn’t know Blake for quite a long time. And when I first saw his images, I didn’t quite understand why people were showing them to me. I didn’t see I had anything to do with this, or what it was saying, or the sentiment behind it. And then, thank God, The Flea arrived.

The Flea changed everything. It stopped me in my tracks. It’s the most astonishing thing I’ve ever seen, this tiny little picture. It works in every conceivable way. It’s dramatic, it’s cinematic, it’s got multiple lives, multiple universes, and it’s a presence. This is not a vague presence. This is something muscular and dangerous. This is something that is prancing across the stage. And I kind of fell in love with it.

One of the things I have, which is probably a defect—you don’t you call them defects these days, they’re probably neurological differences, whatever the word is—is that I can’t accept things for what they are, I have to take them on, I have to become part of it, I have to adopt them, I have to take them into my hand, and into my heart and my mind and my dreaming, to understand them. To remake them, I have to find a way to be in that room with that creature, and not be seen by it. This sounds like kind of fantasy but is not a fantasy. This picture was so real to me. I wondered about how the stage was made. And what is that thing to the side of the curtain that looks like a cactus? There are things in it that are so odd. And it’s all painted on gold. Blake did a series of experiments, putting gold leaf on and then painting over it, which kind of ruined the painting. The painting is falling apart because he put tar and other chemicals in. But it doesn’t matter. It’s an alchemical image, both in its structure and its meaning. It’s alive.

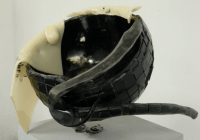

I think the fixation of trying to guess what Blake was thinking is a waste of time

I don’t have a passive position. So the first thing I made on the way to understanding what I was looking at, was the object he’s carrying in his, hand the bowl. The bowl is there to collect blood. There’s no other function. That’s what it’s for. If I construct something it’s not an identical copy, but a kind of contemporary remake. And of course, in the process, it becomes cosmological, it becomes planetary. But it can be held in the hand there, a rather bigger hand than the human one. And it is a composite object. It’s made of different things. It’s essentially black perspex and ivory perspex. But it’s got steel in it. It also resembles the sort of medieval shaving bowls that used to be carried around the streets of London, which people would strap around their necks to be shaved. There’s something domestic in this. There’s something known, but it’s also in a condition of strangeness. It is an enigma, haunted by partial recognition.

At the same time, I think it was 1988, The Blake Society asked me to make a performance in St. James’s Piccadilly. This is the only image I have of it. And my memory of it is completely gone. I remember that on the outside of the church—because the church has parallel, clear glass windows—I had people on either side with mirrors to reflect the sun inside, to dapple the interior. But what the performance was, is gone. I’m convinced that the more you write fiction, the more it makes the memory transparent. And this is a classic example. However, I did find a little tract that said that I was crawling along the aisle. I was being something between the Flea and Nebuchadnezzar. I found a golden halo that was actually made of clay. And when I wore this thing, it fell apart. It became soft, it became the wrong material. What these other guys are doing with me, I have absolutely no idea. I’m afraid this picture has gone into mysterious territory. And I like that very much. I like the fact that I don’t own it. And the good thing about performance is you never own them. The artist is a participant, like the audience, for the duration of its existence when it’s performed it’s gone. it resides only in the memory of those that witnessed it. curated in something deeper, than recollection. And perhaps it has become a little bit embedded in the place.

The invention of demons and angels, their imaginative construction, making such things plausible, has always been significant to me and still is

At the same time, I had my first show at Matt’s Gallery, called Lair. The idea was to imprison and encourage angels. It was a cave for angels. And this was on one side of the invitation card, and a little book of information that a visitor would get, after they climbed up sixty or so iron stairs on the outside of the building. What they didn’t know was under each stair was a white feather. When they entered the room, there were a lot of other white feathers on the window panes. This is an image of an ancient carpet that I’ve etched into steel, and then blackened by heat. This was under the last step before you entered the gallery. So you’d walked on this, the physical version of the image that you’re holding in your hand the first page of the book you were given on arrival.

The next page of the book was a calendar, a manual of the clocking-in hours of the day and the week by angels. These are angels of protection, and this is their duty rota. This is an astonishing idea. So you’re confronted by this list of names, it’s pretty clear that they are angels. Inside the gallery, it’s blinding white, it is very brightly lit. Everything was over-lit, causing the eye problems in focussing. One wall of the room is a window, made of many different panels of glass, a feather attached to each. There was tracing paper hanging down, covering the window, moving slightly in the breeze. The light coming from the outside made the shadows of the feathers shift in and out of focus, as the paper moved backwards and forwards, very softly.

The things in the room, you could barely see. They’re made of perspex, of vellum and parchment. And they’re such objects that might attract the curiosity of angels and encourage them to settle and maybe nest. This was made in the way that I was making things at that time, and still do to some extent, in which I bring the material into the studio or the gallery, and I let the material speak to me, to tell me something about itself. I don’t just bring it in as a dead thing that I then cut and chop, and change, and stitch and weld together. These sheets on the floor are vellum, made by a master craftsman, Mr Vorst, an Orthodox Jewish man living up in Stoke Newington who was making these things for sacred books. And he gave them to me, and I brought them back, and I couldn’t touch them. I couldn’t cut them. I couldn’t manipulate them. I put them on the floor and let them tell me what was going to happen. So the objects in the room came from these sheets. Influenced and guided by their individual form, colour and history. removed from their purpose to receive holy script.

This was a kind of disc, that might be a plate or a halo. It was dented by a sperm-like appendage pushing into its surface and forcing it up against the cover behind was another sheet of parchment. The relationship between parchment and plastic is not a good one. But I was trying to find a way to let them speak, to let the materials exchange something about their alienation, and something about their peculiarity, and to suggest an intimacy that was not a natural one.

The great image, the overpowering image of The Flea. This is the famous drawing of an apparition, the drawing taken from what Blake said he saw in a seance and drew for his friend, including the detail in the bottom section of the mouth. But there’s something odd about the normality, something about his posture. This is a man Blake knows, someone he has seen in society.

It is said that one of the things that may have influenced him was Hooke’s Micrographia. This image from Hooke’s book had never been seen before, this vast picture of what a flea looks like under a microscope had never been known. And there’s some evidence that Blake saw this. I thought that was extremely interesting, because he didn’t copy it. He didn’t make a picture of it. He found something else in its intensity, and perhaps in its personality. And I thought, that’s a really good idea.

So I looked to see what was new in the world of the microscope and the flea. And this is what was occurring at that time. This is the head of a flea, which is beyond recognition of anything we could possibly imagine. I thought it was a wonderful sculptural object, but I wasn’t making sculptures, I was making portraits.

Because Blake’s picture of a flea is a portrait, I wanted this to be one too.I deciding to make it the Flea in triumph, a terrible creature.

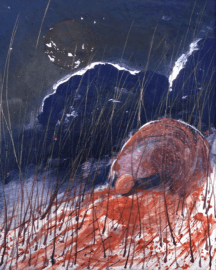

I went on to make a series of things, some of which I threw away, and some of which I kept because I thought they had more to say. So, this is the body of the flea, this is it where it is, with some kind of recognition of time, and the eclipse and the movement of the creature. So this is a shift between being human life , and actual scurrying animals. I’m trying to make an identity kit of a Wereflea.

One of the best ways to find something is to look just to the side of it, to see what its companions look like. So this is a mite, in its landscape. I can’t describe what it is. I can only describe what it might be in another place by not talking about the thing itself.

I think this is something that Blake did. I never had an interest in trying to find the man, because he made so much work to talk about the world he was in, and the world he saw. It wasn’t about him. I think the fixation of trying to guess what he was thinking is a waste of time. I think one of the things that gets bypassed about him is that he was a grafter, a worker. And he produced so much astonishing stuff that is not about him, it being projected outwards from him, and that’s the gift. That’s the only way we’re ever going to find any kind of sense of what it means. We won’t find the man because he is constantly inventing another world to live in and providing all the evidence of its existence.

These pictures become a bit ghostlike in a very different way. While writing these… I mean, while painting these—you see I can’t even tell the difference between the painting and the writing—I started to write towards it. And so these are bits and pieces from a book called The Pittancer. The Pittancer in a medieval monastery is someone who is given a little bit of money to buy little things like spice, and herbs, and flowers, to just brighten the food, to enhance the life of those who dwell in frugality. It’s a way of changing the reflection of the normality of the world. I think Blake was a pittancer. So I started to write about these paintings.

A hutching glow, beneath ghettoed tar and tiles. Embedded in squalor’s parlor. far off a pin prick of cuprous light in the municipalities broth of night

The flea common and uncocked at the black gate, newly painted over by a noon wife, almost departed from the hard crawl of crusted morn while he, tangoing divine is Jewish Bakelite & deliberate, congealed. crying antique, European fawning east.

Our blood shrivels quiescent from the varnish of his gloomy cup, born haughty like a milk lamp grailed or circused on a murder stair.9

Brian Catling9

The populace moved in caution at the exchange of light, and labour, hushing between the clamour of day and the fierceness of night. You could hear London’s breath between its humans at this hour. Even the river held its tides, in its deep ragged throat. Thousands of stacked wooden rooms creak and shudder around their histories. High in that leaning dark is his tenement of ruin. Its interior walls roughly pasted with brown paper and lit by grume candles that cough and Copper taste the thick air. He prowls and fauns in an arrogance of sneering isolation. Posing before an oval brass mirror that wedges the door closed. He shines in the bitter light; a shellacked parasitically herald, princely in its glut. There are many like him befouling the faint health along the rivers edge, and all of them tiptoe in this time of poised congealed waiting. Stretching, waking in the suns last stain. He turns again, adopting another courtly gesture from the rudiments of the genteel. This attitude is the stance; The Complement Retiring.

The room holds its dirty voice as he bows, one hand tucked above his embroidered waistband the other sweeping backwards, gliding sideways holding the stained bowl like an elegant three corned hat. His eyes are down turned. He steps carefully backwards, his gaze never leaving the haemorrhage pattern of the floor.

Others of his kind will evolve into different version, they will all be betrayed by their posturing and their hunger. Being nocturnal, his locked day sleep is Disney bright, the same dreams of impish atrocity curdling in a wide America sky, in advance of its blue, he peels the tobacco bark off of his face like a nut. The fresh green grins below, newer than animation the old head is revealed, in child like dynamism. The locust smile of Jiminy Cricket. That little cracked voice, uncle safe and almost giving the game away by wishing on stars. A navigational infestation, plague driven by folded galaxies.

Others of his kind will evolve into different versions, they will all be betrayed by their posturing and their hunger. Being nocturnal, his locked day sleep is Disney bright, the same dreams of impish atrocity curdling in a wide America sky, in advance of its blue, he peels the tobacco bark off of his face like a nut. The fresh green grins below, newer than animation the old head is revealed, in child like dynamism. The locust smile of Jiminy Cricket. That little cracked voice, uncle safe and almost giving the game away by wishing on stars. A navigational infestation, plague driven by folded galaxies.

Or in Vienna through another looking glass where Hitler carbon copies the same stances grown furious. Fists held above his slopping body in a monochrome bull fight pantomime. A mirrored rehearsal of mania, Victorian wooden, blood thirsty and impotent. The flea practising Triumph.10

This is another flea bowl. It’s a calmer object. It’s a more sophisticated implement that had taken on some of the characteristics of the creature that owned it and used it. Again, it uses a different kind of perspex, forged steel and carved wood. I tried to use these material against , theirselves to turn into bone or to ivory and twist out contradiction. These are very physical things. I twisted in such a way that I’m using temperature and force to stain it, to make it not a pure plastic object. There is a reflecting bowl in the centre of it. And its other parts are like implements coming together for a purpose. To cluster to become one identity but I don’t know what that is. The flea might. But certainly, it’s got a dark interior. And it’s got a kind of anatomical hunger.

These details are the extremities of one of the parts of the thing. This little hook is actually taken from an eighteenth-century tool that I bought and transformed. I cannibalised it. I wanted something of the time of Blake to be actually in the object. A fragment of claw-like tool that he may have once used.

Not all objects are made to last, not all objects are made to be contained, or to be owned—in fact none of them are made to be owned. Sometimes they’re about being alive and existing for a very short time. And those things and often called props, when they are attached to a performance, but I don’t have a clarification between prop and a sculptural object when it’s used in performance. These things were made for a commission called Small Acts at the Millennium.11 Where a group of artists were asked to make responses to the change to the great rolling of a century. And I wanted to make something about recognition and bewilderment, something where, when seeing people on the street, seeing people sleeping, seeing people tucked up on the benches, asking how you knew they were people, how you know they aren’t bundles. I wanted to blur the territory. And I wanted to make a moving, itinerant performance, a kind of hit and run thing where I would occur, make things, so that no one knew. This was never announced, I’d just arrive and do something. So on one level this just some lunatic in a corner doing something. On another level, I’m trying to attach to the place. I’m going to show a little bit of film from this, which shows part of my performance in Bunhill fields, in sight of Blake’s grave.

These works were made in Cambridge and London. They were filmed by a group of people which I had no control over. That was their job, not mine. I would go from one place to the other and make these things happen. At the end, I retrieved all the evidence. And I used it as recorded glimpses to try to construct something. I didn’t use it as evidence of event, I wanted it to be substance, it was the motive and the narrative of the film. So the thing was invented from these extracts and from what I saw and felt about the places where they were made.

The sleeping stone tomb is, of course, Bunyan, who is also buried in Bunhill Fields, and it seemed he and Defoe and Blake together make an accumulator in that place, a battery. And it’s still ticking over.

The invention of demons and angels, their imaginative construction, making such things plausible, has always been significant to me and still is. It’s very uncool I guess to be still painting demons and angels these days, but that doesn’t bother me in the least. And if you are in any doubt about that, you can just go back and look at Blake any time, because these things are still so fresh, and still being used by all kinds of people.

But he’s not the only one. There are other great demons and angels in the world. This is Ucello. This is his Miracle of the Desecrated Host, an extraordinarily weird little painting—landscape and architecture kind of fused and broken. There is some kind of squabble over a dead person. The angels seem calm but the demons seem rather busy, but they’ve been scratched. Their surface bodies partially erased Now, I don’t think that was the artist, but I don’t know. But it’s a very interesting and violent detail.

And one of the only ways to find out is to repaint it. So I did. I separated their wings and separated their bodies, so their wings have one conversation in the back of the landscape, while their bodies have another one at the side of the table, but there is no body being fought over. This is called Unshriven With Company. If it works, its atmosphere and its mystery will combine to keep the story going.

Now we have something very different. I’ve never shown this. This is kind of thing. Blake would like this. This is a mistake, this is a disaster. These are the angels in the biggest gallery space at the Royal Academy. High up on the walls near the ceiling. I was asked to become part of the summer show. I said I’d love to make a piece in this room, a sculpture in this room that responds to the angels. This was deemed and approved as a good idea. So it was made and I loved making it. It was a reconstruction in a very different way. It was like one of them had fallen off the wall. On the way down, it turned in something else. So it was constructed. The idea was that it went into the gallery, to live with the other sculptures and paintings during the Summer Show, with the public walking around examining it. But every so often—once, two or three times a month—I would come in, and I would make it come alive. I worked out how to do it. I had mechanisms contained within it and ready to go. And it would startle the audience by the fact that could move its wings. And it could have a life that was not mechanical. It was a pleasure to make, constructed with very lightweight material then covered so it looked like a very heavy material. It looked like inert clay, it looked like stone, it looked like gold. And it was finished. And it was a big thing. It filled my studio and was anxious to fulfil its purpose, waiting for it to arrive on site, which it did, on its stretcher.

I then waited for a telephone call to call me to go in and put it into place. Then it all went wrong. A whole series of things changed, a series of curatorial decisions and technical aspects shifted. So in fact no sculptures were to be shown in that gallery. I was asked if I could show it in another one: impossible. It was made for the Angel gallery and couldn’t go anywhere else. So the apologetic curators suggested a series of compromises that might work out—it might become this, or might become that. In the end, I was offered a site underneath a fourteen-foot fibreglass copy of the Pink Panther. At which point I said no, I don’t make things for circuses and pantomines. So it’s over. It’s done. It can’t come back to me. It doesn’t live anywhere else. It was born for this one room, to come alive in this room. So I said I’m sorry, you’re gonna have to chuck it. They said, “what do we mean?” I said, put it into a skip, it has no function anymore. So I had to sign away its potential existence to allow this to happen. I walked away. It went, it was gone. It disappeared. But nothing disappears really. I still liked some of the elements of the images I had photographed, I had forgotten about that angel. The angel never took flight. Something like it one day might, who knows?

So, I had these images, and was making composites, photographs of these things, and then drawing over, and painting them. And I developed a technique of etching and making prints. Blake invented processes all the time, every day he was trying new things out. I’m not suggesting I have anything like his ability. What this is, is that image made on paper, engraved by a laser. So the machine is cutting the surface of the paper in a very minute way. And the colour variations are caused by burning. So there’s no ink. There’s none of that in the process. It’s all caused by removing the surface of the paper and scorching it. And sometimes inventing processes like that gives you a way of understanding the image, coming to terms with what’s actually there, and where it may go next.

This is another. And at this point, I suddenly realised something else. These are two poems again from The Pittancer and it’s about Peckham Rye. I grew up in South London, near Peckham Rye. It was not full of angels and trees—very far from it. But every time I walked there once I knew that Blake had seen them, I always wondered which tree it was. Could it be the same tree? Could it still exist? Could its roots be there even if the tree wasn’t? So I wrote these two pieces.

From out the mouth cut saw a bitter gall, ink hidden in boiled and drained Angel sleeves, Sitting in that now most unlikely tree.

The Rye ghost Love & Hate tattooed on either hand. Hands matured with the wood polished to tale on more than bless.

It is a suit dummy fastened tourist to a scarecrow’s sight, propped to clue the quarried vision’s tilt. Fake as the poet’s stone, name carved in absences of the body’s scent. The true intelligence is graced elsewhere.

The tree itself has shuddered out, inverting its gesture in vaulting mirrors beneath the pitched soil. The Roots describing the exact branches of that day, the very twigs configured to the moment that he saw woven between the wind and rain, a smile in the trembling leaves.

Today, the needles and dog shit have calligraphed a signature, on the spot, over the stump sealed by a scarring of indifference: time’s Insolent lime. The roots have twitched sucking night down to beckon & wave in another light compressed by the a darker groaning loam, squeezed into sound and the raking opposites of shadows that flatter the illuminations of worms, in this little air land of hearing.

Brian Catling12

This is another performance that only happened once, because lock-down kind of exiled it. This is David Tolley’s portrait of me making it in the studio as a kind of a rehearsal for the real thing. Again, putting it through processes, putting it through different ways of seeing and rewriting it, retelling the story, pushing it through the same engraving of paper. So it becomes this tiny surface, and these tiny surface activities that the image. And then painting the image as if it was still life sitting before me.

The angel thing continues, it keeps going on. And I realised how much Biblical stuff there is here and how much that kind of goes beyond the biblical, purpose to seek out something further away.

This is called Visitation. I don’t know what it’s about, but it’s a visitation. And it’s taken from pictures of certain things—certain buildings or certain paintings—that have been resurrected. This is called Lost Angel Found, and it’s another kind of landscape. It’s another building. It’s another structure in which to walk into. And it’s busy. It’s active between Earth and somewhere else, it’s thriving. And our position to enter it is one of pure imagination.

Sometimes someone offers you a challenge, a fundamental challenge. I’d made a processional cross for Dorchester Abbey, dedicated to a friend of mine who died. This was a discreet action, but had become noticed, and I was asked if I would consider making a processional cross for St Martin-in-the-Fields. Which I found a really interesting challenge—a cross is fundamentally simple: two pieces of wood. But St Martin-in-the-Fields is a very particular place. It’s known for several things. its charity and its work with homeless people. being the most dominant in my eyes. If somebody had faith enough to want to make a crucifix, how would they make it if they had no materials, no money and no skills. They had nothing but two pieces of wood and a piece of string? So this was my beginning to make a processional cross that is actually a cross of poverty. So I started to experiment, making different forms of crosses. And once you start to play with this thing—you know, how basic and how significant it is. But once you start to play with that, all kinds of other possibilities come forward.

Eventually, after inventing all kinds of cross-hybrids and variations, I settled on this one and added a third element, St Martin’s cloak. The Saint gave his cloak to a beggar. He made himself semi-naked by tearing his own clothing in two Now, if I add a third element to a cross, that wasn’t a body, but it’s something else. It means that when you carry it through space, or aloft, it becomes a three-dimensional object, not a flat thing, not a two-dimensional object. So these pieces of wood and string were then turned into more solid material. I normally make all parts of a work with my own hands. I don’t farm it out. But sometimes the process of making demands to be transformed—in this case, cast in enduring metal. That couldn’t be gold or bronze because they would make it too heavy to carry. So it was cast in aluminium, but the aluminium is covered in gold. It keeps all of its original surface and all its original sculptural movement and form. When the Moon gold leaf was applied It suddenly changes the object completely and you’re not sure what you’re seeing. And when you see it presented in the church and, from a distance it looks like an ornate medieval cross. But at close, intimate range, it again becomes three pieces of wood tied together with string.

I wanted to show you a comparison and an opposite. This is called Blind Crook. It is like a shepherd’s crook, but a big one. And the bottom half of it is white, signifying a blind man’s white stick, but the white is coming from its interior. There are holes and little fissures in this that leaked the whiteness. So its blindness has come from the inside. I guess it’s a political work: you wouldn’t trust this shepherd. But I want it to be a kind of artifact. It’s is a remnant of bad leadership, but we want it still to have a majesty, a kind of presence.

I wrote these three books. Or rather they used me to write them. I don’t remember making any decision about that. They just occurred. I’m going to finish by reading the opening section of The Erstwhile. Blake was there, in it. He was an implication. He was there as a presence. In the first book, I used real people like Eadweard Muybridge and Sir William Gull. And so in every book, I wanted there to be a real person among the fictional ones. Blake was never to be it. I was greatly encouraged by my editors to reconsider this. They practically accused me of being cowardly by not bringing him in. They said I was skirting the issue. Okay, that’s a challenge. All right. If I can do it in the opening section, he’s in—but not a lot. Because I’m not writing pictures of Blake. I’m not going to tell you who he is. That’s for you to decide, by considering the work he made.

So I’m going to read this opening section. It’s a couple of pages and then leave you to think what you think.

This is where the man-beast crawls, it’s once-virtuous body turned inside out, made raw and skinless, growing vines and sinews backwards through the flesh, stiff primordial feathers pluming in its lungs, thorns and rust knotted to barbed wire in its loins. Guilt and fear have gnawed the fingertips away to let the claws hook out into talons. Sharpened by digging a home in a shallow grave. It is seen on all fours, naked, and worse across the broken ground on sharp knees, which are red raw from chiseling the earth to gain some purchase. Prowling inside a trench blinded by the stark glares of explosions. Another bellowing flash sculpts the rippling muscle of its back and arms and the thick prophet’s hair has become soured by warfare into itching dreadlocks. mud-filled like the beard or dribble and tangled ginger grit.

But it is the face that alarms, skinned alive by shock.

The eyes terrified in the sudden phosphorous glare. Ultimately lost and forever in a gutter of staring that has emptied its skull.

The small balding artist makes a further adjustment to their expression, widening the pupils, setting them in a squint, looking in different directions to give insight into the mind cleaving.He then steps away from the table with a picture being made and nods to himself, his ink stained fingers rubbing his chin. Yes, it was almost ready to be finalised for printing. A small noise on the other side of the room made him look up and drag his thoughts into the open: “I say it’s almost ready to be finalised.”

Someone or something was draped against the shabby curtain that was saturated in the stink of London. The artist took the picture from the table and held it up to show his subject and emphasise his words.“I never looked like that!” came the reply. “You caught me between worlds upriver, before I left the great forest and downriver after. You have gone and left me here alone, and all the other Rumours have sailed over to the Dauphin’s land to be torn apart in the mud, in the first of your world wars of which there shall be many.”

It was difficult to understand the model because he had been speaking in a vocabulary of shadows. He had not yet learned language. Instead he spoke into the artist’s mind telepathically, without words, which made the artist’s mouth work unconsciously, trying to shape the sounds in his mind. For anyone else, this manner of communication would be shocking, but for this painter, it was just another day communing with the angels.

The model said he was of the Erstwhile, but this made no sense to the painter. He also referred to humans as ‘Rumours’, with a capital ‘R’. It all seemed to be a bit delirious and the waning day outside was blurring the edges of their meanings. The model’s statement about a French trench in a future world war had not been understood.

The night closed slower back then, the eye calibrated to dusk and all the nuances that have since been removed and exiled by the illumination of gas and electricity. The city in these days was encrusted in an ancient gloom—the small wicks of the whale oil lamps glowed in every tarry hutch, doing little but adding a smoked glitter to the polished coral of London’s darkness. A blind man, and there were many then, could tell you the time of day by the change of smell, as the whale oil’s stench rose up against the departing light. The river held the tides in its deep ragged throat for a moment before reversing its might under the command of a hidden moon. On the banks of the Thames thousands of stacked wooden rooms creaked and shuddered.

The painter protested: “But it is you exactly as you described it. As you looked before. Before you found me. It’s you leaving that forest. Fleeing that Vure you speak of.”

“V-O-R-R-H! and I did not flee.”

This was announced in careful curves with a new insistence, in its pressures, forcing the artist to drop the picture and hold his head.

The abruptness surprised the last particles of day.“Do not write my name on this. If you must show it to others, say it is someone else.”

“But who? What?” Asked the confused artist. “Nothing else looks like this.”

“Then hide it, bury it under others, show no one, burn it.”

“But it shows another face of God,” the artist said. “God in the beast and man declining, falling from grace.”

The model maintained his clarity while dissolving in the gloom.“An ancient king,” he thought, tossing it back in the wake of his leaving, and the wisp of it undid the pain in the artist’s temples. He took his hands down and looked at his stained fingers as if trying to match the same darkness and the pigment with that which was growing in the room. He then looked up to find the silhouette of the companion of being that accord himself an angel, but none was there. He bent back to the picture.

“I will call it Nebuchadnezzar,” he quietly called out, in the way one speaks to final closed door of a departed lover, the fleeing absence of a once-attentive listener. It became one of William Blake’s greatest works.

Brian Catling: Avoiding Blake: Defeated by a Flea in the Ear (Video)

A talk given to The Blake Society on 15the Dec 2021.

The slides for the talk can be seen here.

Resources and References

B. Catling & Lucile Hadzihalilovic, Earwig, a film by Lucile Hadzihalilovic.

B. Catling, Earwig, London: Coronet, 2019.

B. Catling, The Erstwhile, London: Coronet, 2017.

B. Catling, Hollow, London: Coronet, 2021.

Simon Perril (ed), Tending the Vortex: The Works of Brian Catling, Cambridge Conference of Contemporary Poetry Books, 2001.

The post Brian Catling: Avoiding Blake: Defeated by a Flea in the Ear, a Talk to the Blake Society first appeared on The Traveller in the Evening.

BBC4 Arena, B. Catling: Where Does It All Come From?, first broadcast 6th Nov 2021, www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0011v76

Brian Catling, ‘Interview with Ian Hunt, Jun 1993, in Brian Catling, Simon Perrill (ed), Tending the Vortex: The Works of Brian Catling, Cambridge: Cambridge Conference of Contemporary Poetry, 2001, p14.

Brian Catling, ‘Interview with Ian Hunt’, Jun 1993, in Tending the Vortex, ibid, p15.

William Blake, Jerusalem II 30/34:55-9, in David Erdman, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, New York: Random House, 1988 (1965), p177.

William Blake, ‘Proverbs of Hell’, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in David Erdman, ibid., p35.

William Blake, Letter To Thomas Butts, 22 November 1802, in David Erdman, ibid., p722.

Brian Catling, ‘The Electric Influence’, in Necropathia, London: Albion Village Press, 1971.

Iain Sinclair, Lights Out For The Territory: Nine Excursions on the Secret History of London, London: Granta Books, 1997, p260.

B. Catling, The Pittancer, in A Court of Miracles: The Collected Poems of B. Catling, Etruscan Books, 2009, p238.

B. Catling, The Flea: Reflections on Blake’s Ghost of a Flea, in A Court of Miracles: The Collected Poems of B. Catling, ibid, p244-5.

See Adrian Heathfield (ed), Small Acts : Performance, the Millenium and the Marketing of Time.

B. Catling, The Pittancer, in A Court of Miracles, ibid, p238.