The Bloom had Gone

Our generation’s illusions are lived ones.

John Game

How the right appropriated what were once left wing causes – ‘no forever wars’ for ‘anti war’, ‘anti-globalism’ for opposition to neo-liberal globalisation and hostility to ‘elites’ for hostility to capitalism – is what led some on the left to believe that even in a period of unprecedented right wing reaction this was still their era. This ignores two things. Firstly, that the terminological shifts matter and have real content. ‘No Forever wars’ ‘globalism’ and ‘the elite’ stand for a conspiratorial worldviews as much as what they claim to stand against. Parochialism, ‘multi-cult’ and hatred of all liberal and progressive values at home and abroad are the real content of this stuff and they are at least as popular with the right’s base as the more left-wing concerns they appear to shadow.

There is much that needs to be re-thought after a few decades where analysis was replaced with a strange doctrine of eternal return where every battle was treated as the occasion for the resurrection of old socialist slogans. A strange form of idealism where idealism was dressed up as materialism in an endless nostalgia for yesteryear’s battles, which eventually replaced the present in our own minds.

Fans of the dialectic might enjoy the irony of a defeat for neo-liberal globalisation being the greatest defeat for the left and progressive values seen since the 1930s, where hope lies with the stock exchange putting some manners on right-wing politicians. But perhaps these dialectical paradoxes point to the completely false perspectives we’ve carried around for more than three decades.

The power of the past hangs like a nightmare on the brain. And this was particularly true of older collectives of intellectuals on the left. The tragedy is that you need collectives and collaboration to work out new forms of politics. Today, there is almost nothing like that that doesn’t simply consist of repetition or self-affirmation.

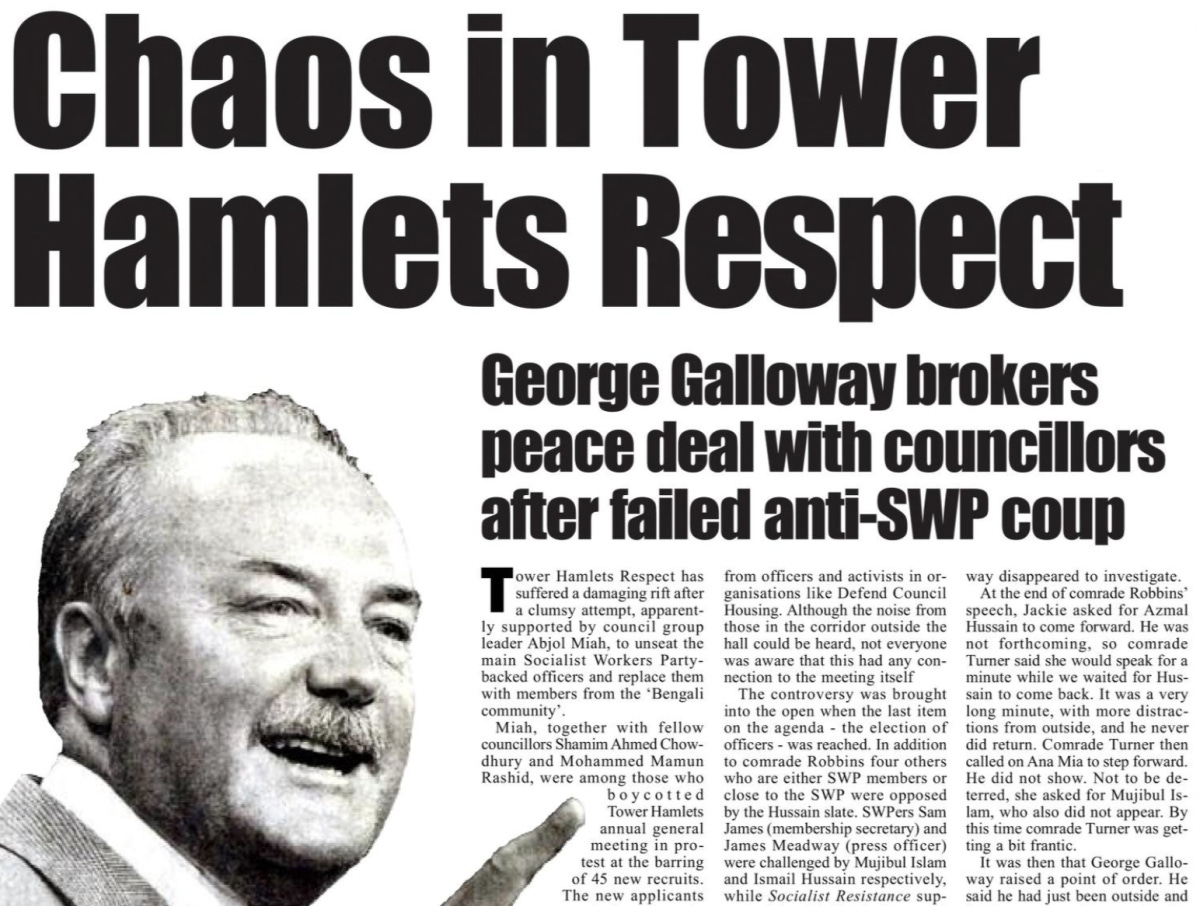

In some ways, this is the material basis for the revival of campism. All through the noughties as we built opposition to war and Islamophobia, UKIP was growing. The infiltration of the left by reactionary discourse was the blurring of distinctions between right-wing forms of isolationism and left internationalism, which happened because people overestimated their own influence and vastly underestimated the growth of KIPper discourse. This was seen clearly with the increasing difficulties in even being able to mobilise against the EDL effectively. By the next decade Stop the Wars’ talking points on Ukraine to Syria were almost indistinguishable from the right’s weird mix of conspiracy theory and parochialism. This is the real story. George Galloway was only the clearest example of this degeneration.

John Game, 2025-04.

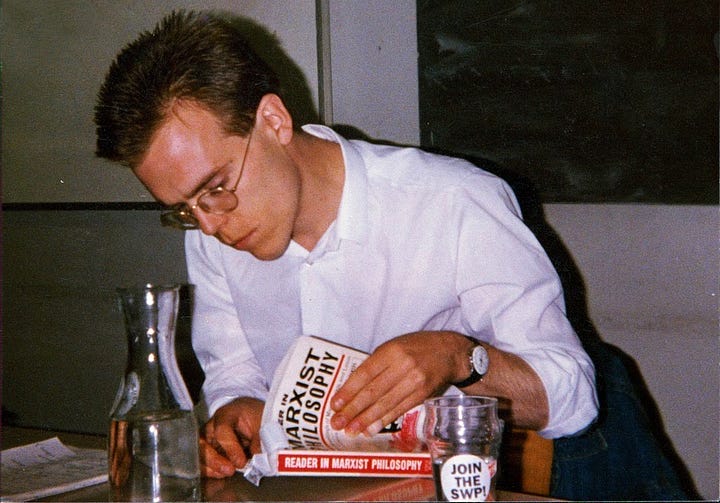

Now what is happening around the Greenham Common women is tokenism. You can’t just say they are feminists, or separatists. That is not the real reason for their actions. We have to ask why tokens come to the front. Tokens come to the centre when there are not any real forces to solve the problem… Tokenism is at the centre of the downturn here. The trouble is it does a fantastic amount of damage.

Tony Cliff, ‘Building in the Downturn’, speech to SWP National Committee, 1983.

The Collapse of the SWP and Decline of the Far Left

John and Andy discuss the growth of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the 1980s, the party's response to the miners' strike defeat, and the shift in international perspective from "Neither Washington nor Moscow" to a more anti-American stance. They also reflected on the history of the revolutionary left in Britain, the aftermath of 9/11, the formation of the Respect party, and the legacy of the Russian Revolution. They discuss the history and internal dynamics of the SWP, the economic and social transformations in India during the 1980s and 1990s, and the rise of right-wing populism in India.

The discussion concludes with John and Andy reflecting on their past involvement with the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and their current views on Marxism and the legacy of the Russian Revolution. John expresses his belief that the Bolshevik revolution was disastrous for the left, as it severed the connection between communism and democracy. He argues that the repression began almost immediately after the revolution, contrary to common narratives. Both John and Andy acknowledge the need for a more nuanced and critical understanding of socialist history, particularly regarding the Soviet Union and its impact on Eastern Europe. They suggest that the traditional Marxist framework is no longer adequate for addressing contemporary issues like environmentalism.

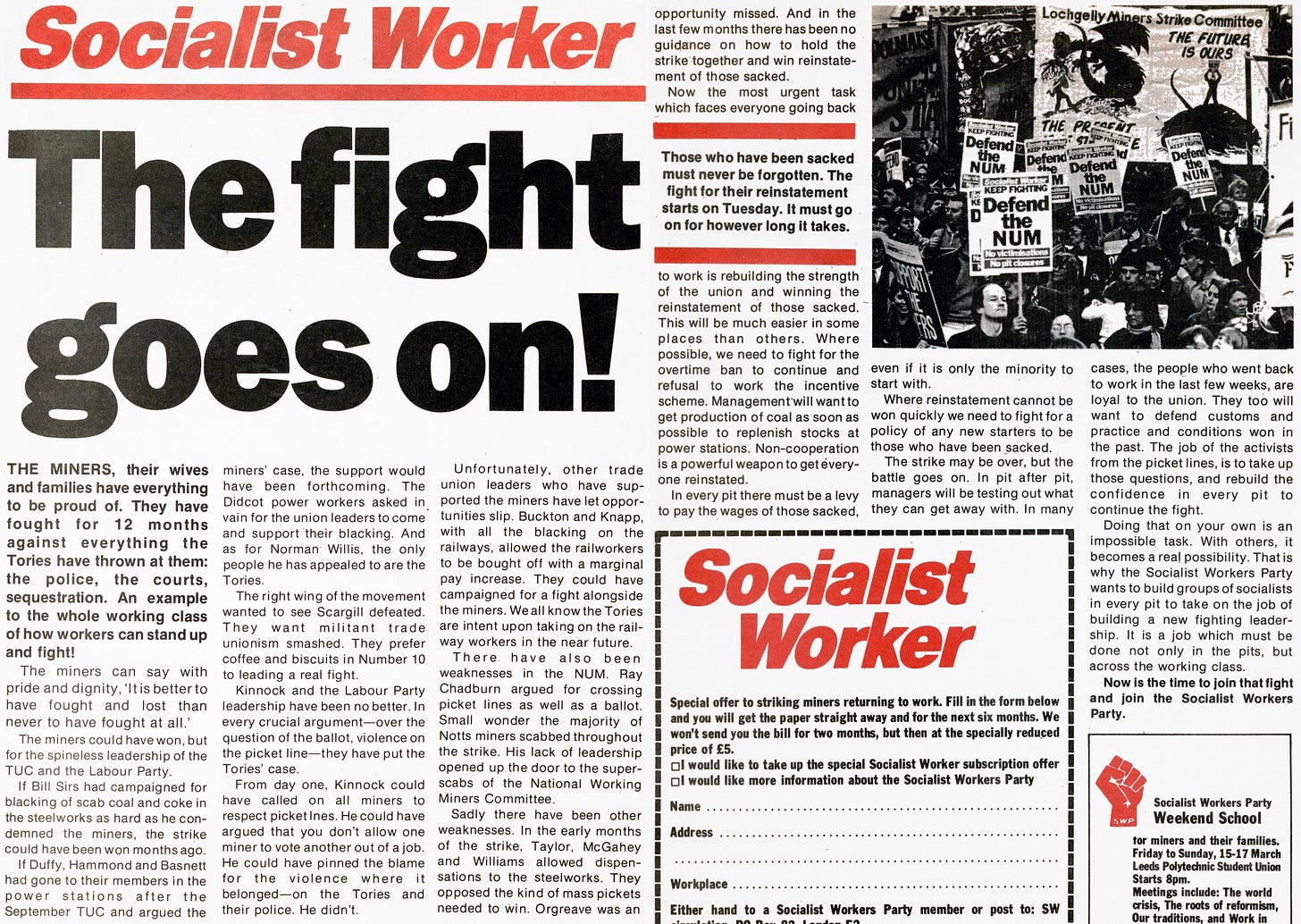

The End of the Miners’ Strike

SWP's Growth and Political Shifts

John and Andy discuss the growth of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the 1980s despite the grim political climate. They explore themes like the party's response to the miners' strike defeat, the shift from industrial militancy to a focus on building the party, and the transition in international perspective from ‘Neither Washington nor Moscow’ to a more anti-American stance. They analyse how the SWP adapted its strategy and rhetoric during this period of change in left-wing politics. The discussion will cover the party's growth, internal dynamics, and eventual decline, while also touching on broader trends affecting the revolutionary left.

Andy and John discussed the history of the revolutionary left in Britain, focusing on the period after the defeat of the miners' strike in 1985. They highlighted the paradox of the 1980s, where, despite the grim situation, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) grew in membership. They attributed this growth to the general political polarisation created by Thatcher, the desire for ideological resistance, and the SWP's ability to relate to a highly political situation. They discussed the shift in the SWP's approach, from defending past positions and the centrality of the working class to addressing political questions and being tribunes of the oppressed. However, they note that this shift led to a culture of unanimity and voluntarism, which became problematic. They touch on the SWP's involvement in the Respect coalition, which they saw as a manifestation of the organisation's problems.

1983-85: Liverpool Council

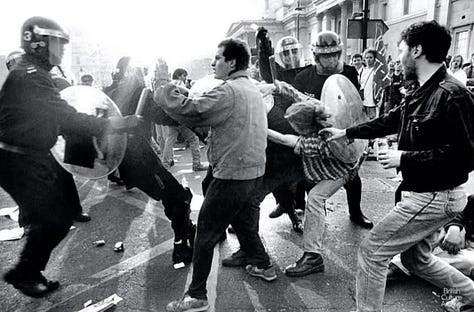

The Poll Tax

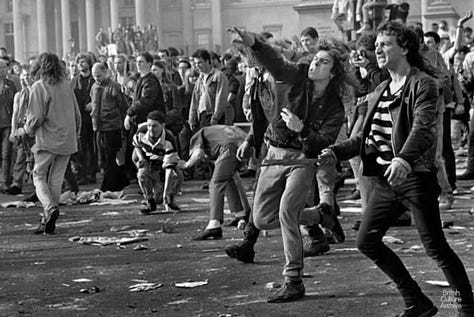

The SWP were late to the Anti-Poll Tax campaign, having started by insisting on the need for council workers to take action to defeat the tax, they took a while to join in with the Militant-led campaign on community non-payment.

Stop the War Coalition (StWC)

StWC was established on 21 September 2001 to campaign against the impending war in Afghanistan. It then campaigned against the impending invasion of Iraq. StWC never clarified the basis of the anti-war movement, which increasingly was explained in conspiratorial terms shared by the far right, with their talk of ‘forever wars’.

Just a Little Respect

In 2004 the SWP decided to gamble everything on an alliance with George Galloway, with whom they formed the Respect Party.

Respect Party and Anti-War Sentiment

The discussion covers the aftermath of 9/11 and the formation of the Respect party in the UK. John explains that Respect was presented as a way to capture anti-war sentiment, particularly among Muslim voters, but in reality was about avoiding allying with more militant anti-war activists. He notes that while some criticised Respect for making too many concessions to Muslims, he is proud they stood up to Islamophobia. John observes that during this period, many on the left had an overly charitable view of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) leadership and failed to recognise the rise of UKIP and the far right. The conversation touches on broader shifts in left-wing politics following the fall of the Soviet Union, with anti-Americanism becoming a dominant framework. John argues this led to conspiratorial thinking and a failure to properly analyse events like the Arab Spring.

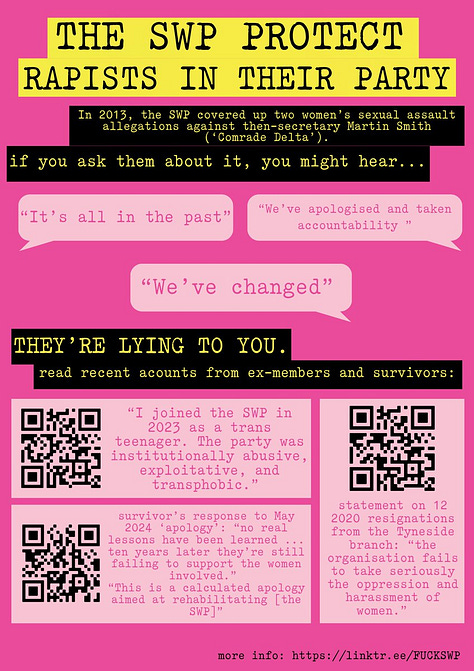

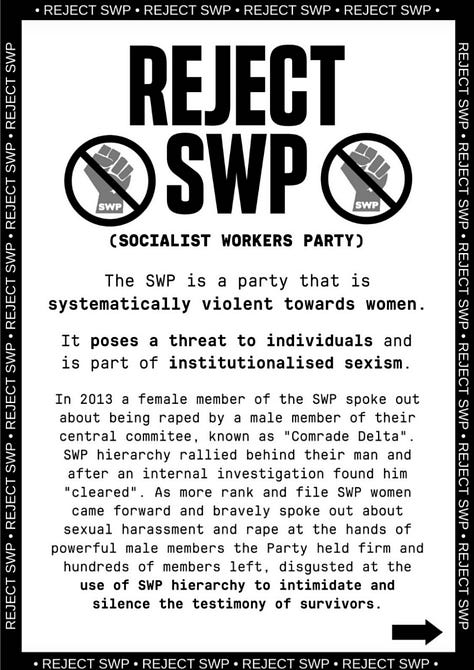

The Delta Rape Case and the Splits in the SWP

In 2013 it emerged that the SWP Central Committee had buried accusations of rape against their National Secretary, Martin Smith. Huge numbers of members flooded out of the organisation to create the groups, the IS Network and RS21. Neither of these made a significant break with SWP politics: the ISN soon floundered, while RS21 maintains a ghost life not unlike that of its parent organisation..

The Bloom Had Gone

The bloom had gone off radical left politics long before the collapse of the Soviet Union. The crisis of Social Democracy was visible from the early 1970s. The developmentalist state of various nationalist socialisms was well in train even by the period of the late African decolonisations of the time. The revolutionary left survived mainly as the radical edge of (distinctly non-revolutionary) battles against the restructuring of capital as the old models began to disintegrate. These battles formed my own politics, so I’m far from condescending concerning them. But it was the fag-end of a series of defeats and disorientations which had their roots a decade earlier. ‘Actually existing socialism’ had been dead as any source of real ideological inspiration to anyone other than its opponents since the tanks rolled into Prague in 1968, abolishing forever any illusions in the possibility of a rejuvenation of the Soviet system as a post-Stalinist ‘socialism with a human face’. In China, any illusions in ‘the Cultural Revolution’ were ditched even by the regime.

The rise of illiberal democracy can be traced back to the period of Bush’s war on terror, one of whose features was politicians manipulating state institutions rather than the other way about. The disorientation of radical politics after a brief mini-boom led to a profound misunderstanding of the causes and the dynamics of these events. This is why the old left language about ‘the deep state’ has become the language of the radical right. It’s a complete misdirection. By ‘deep state’, they mean functioning liberal institutions, which, of course, are their main target. This is the problem with hanging onto older radical languages, both those that were once true and those which were not.

John Game

Nigel Harris: Review of Ian Birchall’s Biography of Tony Cliff: A Marxist For His Time

Tony Cliff: A Marxist For His Time

Ian Birchall

Cliff knew, better than anyone, that a revolutionary party without a revolution cannot fail to become a sect, driven first and foremost by faith and the need for self-perpetuation. The cadres cannot keep their consciousness on ice, waiting for the next bus of history to pass by (a dreadful mixed metaphor, worthy of Cliff himself, and rightly subject to a sharp Birchall rap of the knuckles).

What might have saved something was to turn back to the strategy of the 1950s, rewind the clock to the old political club and start to confront what was now revealed as a theoretical vacuum on the left, drawing the lessons of the failure of the upsurge – especially, as it seemed, the radical decline of the working class and the atrophy of its trade union and political institutions, economic globalisation and the redistribution of the world working class from Europe and North America to Asia.

Perhaps that is what Cliff thought he was doing in writing a four-volume biography of Trotsky, but it smacked of iconography more than ‘learning lessons’. Ian cannot avoid a sober comment: “As the 20th century approached its end, the Russian Revolution…remained the solitary success story for revolutionary socialism. That Cliff in his last years had to return to the inspiration of 1917 (rather than, say, examining the nature of the British working class) was a sign of the weakness of the movement”.

Worse than that, even where workers were involved – in Lech Walesa’s Poland or Lula’s Brazil – workers merely reinforced reformism. It might seem that it was only the voluntarism of the intelligentsia that made a revolution ‘proletarian’; was Marx himself coming apart?

But retreat was impossible (for example, ending the pretence of any longer being a party). It might have destroyed what was left, demoralising the members. They had been groomed for history and would not settle for mere faith. On the contrary, Cliff seemed not to embrace the emerging world but to retreat to the verities of his teenage years, symbolised in his preposterous description of the times as “the 1930s in slow motion”.

All Cliff’s savage mockery of the Fourth International’s efforts to pretend continuous slump and mass unemployment persisted through the boom of the 1950s (because Trotsky said this was the nature of the times in 1938) seemed to have faded. It was worse than that – as massive slump and dereliction supposedly racked the system, China and East Asia soared ahead with rates of annual growth of more than 10 percent per year – and an unprecedentedly resulting massive reduction in world poverty. India was not far behind.

If this was a capitalism in terminal decline, it might seem to the millions marvellous beyond words. Cliff could not avoid some of these issues even if he seemed theoretically on 1938 autopilot. Ian cites a Cliff riposte that shows he was aware of some of the problems of the new world: “the growing integration of the world economy meant that not only was it impossible to have socialism in one country, it is stupid to speak even about capitalism in one country.”

He was scornfully dismissive of those who talked of the decline of the old working class, saying triumphantly that the Korean working class was now bigger than the whole working class in Marx’s time, but with nimble sophistry avoiding the question of what should be the role of a Marxist in this little corner of the globe when the world working class had decamped to east Asia. And if there was to be no repetition of 1917, what was now to be the strategy to achieve collective universal self-liberation?

A continual contemplation of the heroic victories of the past strongly suggested there was no future: these were not lessons of history but epitaphs. In such circumstances, could Marxism avoid becoming a religious cult, false consciousness itself, faith defying all the evidence, will defying intellect? Had Cliff become a tragic prisoner of his own creation? That marvellous facility to reinvent himself – so vividly displayed during the years of upsurge – failed.

He was captive to his combat group, requiring continuous campaigns (some of them were excellent initiatives) to perpetuate its mere survival. There was no time to return to the tasks he did so well in the 1950s in reconstructing theory, much less gather around himself the thinkers required to contribute to this process as was briefly attempted with Mike Kidron in the early 1960s in the creation of the International Socialists. He had become a vested interest with its own dynamic.

Theory had become mantra, to be repeated in unison, not applied. Of course, it is quite unfair to reproach Cliff, after such a life, for not undertaking in his declining years such an immense task, the reconstruction of a critique of contemporary global capitalism, and defining the realistic means to overcome it. But he had built a structure and selected a cadre, defined an agenda and a culture which meant they too could not undertake these tasks.

Instead the criterion of success became survival (with some spectacular successes – the Anti Nazi League, the Stop the War movement, etc), self-perpetuation, and compared to the miserably low standard of other tiny revolutionary groups (a measure Cliff would have indignantly rejected in his heyday – it was not the task of a revolutionary just to survive). Meanwhile, the older cadre slipped away quietly – into having children, pursuing careers, golf or opera.1

Nigel Harris, review of Ian Birchall, Tony Cliff: A Marxist For His Time.

Buy me a Coffee / Subscribe

Ithell Colquhoun: Mantic Stains, Sex & Surrealism

An old woman motionless on a short straight puff of smoke

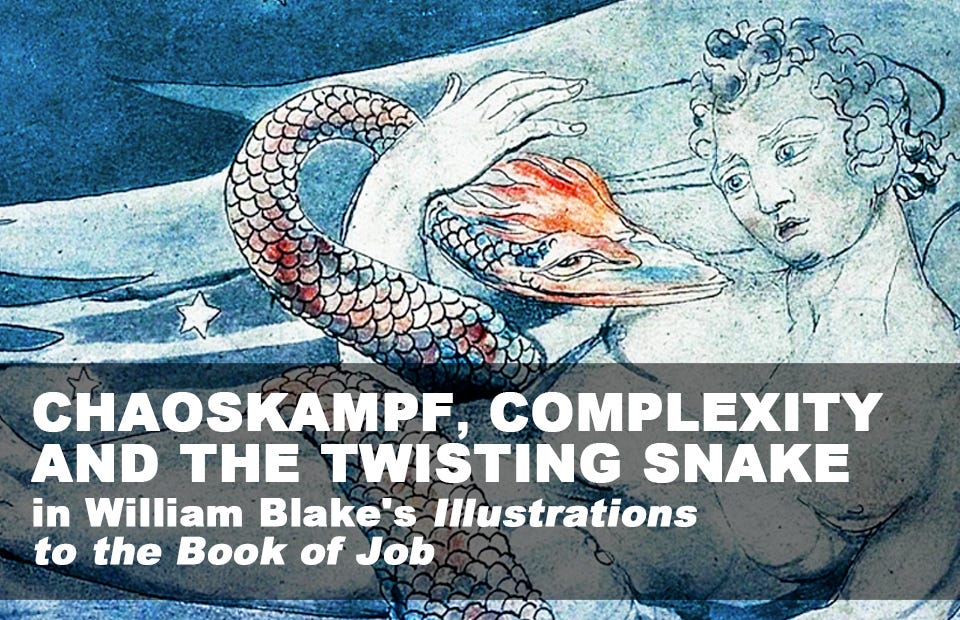

No Place Called Home: Jason Whittaker on William Blake’s Jerusalem and Progressive Patriotism (Review)

The patriotic frenzy around Brexit and the death of Elizabeth Windsor offer an opportunity to reappraise Blake’s song Jerusalem and the nationalistic impulse so many find in it. ‘Jerusalem’ is far more contestable as a vision of England. This book traces the history of …

Blake in Beulah: John Higgs's 'William Blake vs the World' (Review)

Hey Hellbait, why are you waiting?

Golf? Opera?

Share this post