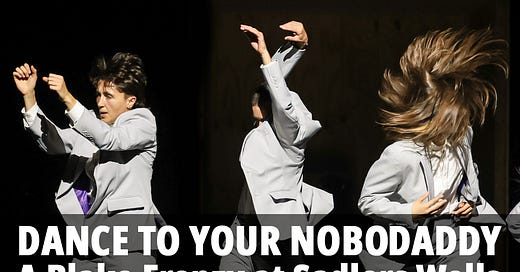

Dance to Your Nobodaddy: Tríd an bpoll gan bun at Sadler's Wells

Folk musician Sam Amidon and Michael Keegan-Dolan's Teaċ Daṁsa's new piece, inspired by Blake's divine dad-gone-bad, Nobodaddy, tells stories of betrayal and loss drenched in Irish history.

Dance: Michael Keegan-Dolan & Teaċ Daṁsa: Aki Iwamoto, Amit Noy, Ryan O’Neill, Rachel Poirier, Ino Riga, James Southward, Will Thompson, Holly Vallis, Jovana Zelenovic.

Music: Sam Amidon, Romain Bly, Flora Curzon, Jimmi Jo Hueting, Mayak Kadish, Sandra Ní Mathúna, Alice Purton, Jelle Roozenburg.

Then old Nobodaddy aloft

Farted & belchd & coughd

And said I love hanging & drawing & quartering

Every bit as well as war & slaughtering

William Blake, 1793.

Oh what will you leave to your brother John

The rope and gallows to hang him on

And what will you leave to your brother John's wife

Pain and sorrow all her life

And what will you leave to your brother John's son

This great wide world to wander upon

Lily-O, sweet hi-oh

Lily-O (trad.)

“You must take one side or the other Or you’re but a fucking romantic”

Paul Durcan, ‘In Memory: The Miami Showband’, 1978.

After wooing audiences in 2016 with a radical revisioning of Swan Lake / Loch n hEala, and with Mám in 2019, Michael Keegan-Dolan is now back with his Teaċ Daṁsa (‘House of Dance’), offering an intense, abstract performance (a “multi-disciplinary dance and theatre ritual“) centred on William Blake’s character Nobodaddy, a merciless and demanding cosmic demiurge, gore-splattered progenitor to Alfred Jarry’s Pa Ubu in Ubu Roi: merdre!

Keegan-Dolan founded the Fabulous Beast Dance Theatre in 1997, then, in 2014, shut it down and publicly burned its archives before moving to County Kerry in the South-West of Ireland to start over again with a new troupe and a fresh commitment to telling and celebrating Irish myth and history (“Teaċ Daṁsa makes dance and theatre work informed by a sense of place and nurtures a deeper more meaningful connection with the traditions, language and music of Ireland.”)1

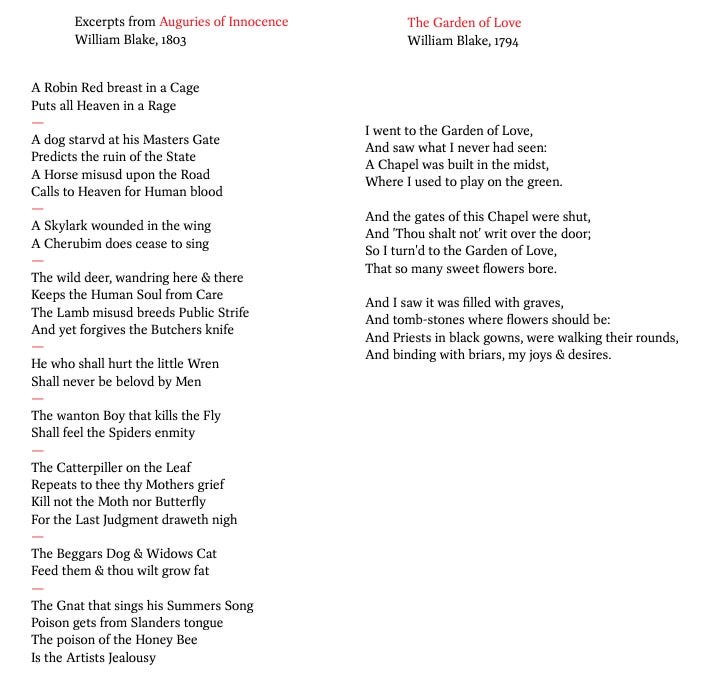

William Blake’s Nobodaddy appears in his new production as its villain. The character is taken from the poem ‘To Nobodaddy’ in Blake’s Notebook, where he is the “silent & invisible father of jealousy.” He appears in other poems in the Notebook (‘Let the Brothels of Paris Be Opened’, and ‘When Klopstock England Defied’), where he threatens and terrorises his victim-subjects.2 He’s a monster sitting astride heaven and earth, divine authority and secular power; the sum-total of history’s theocratically underwritten imperial abuse.

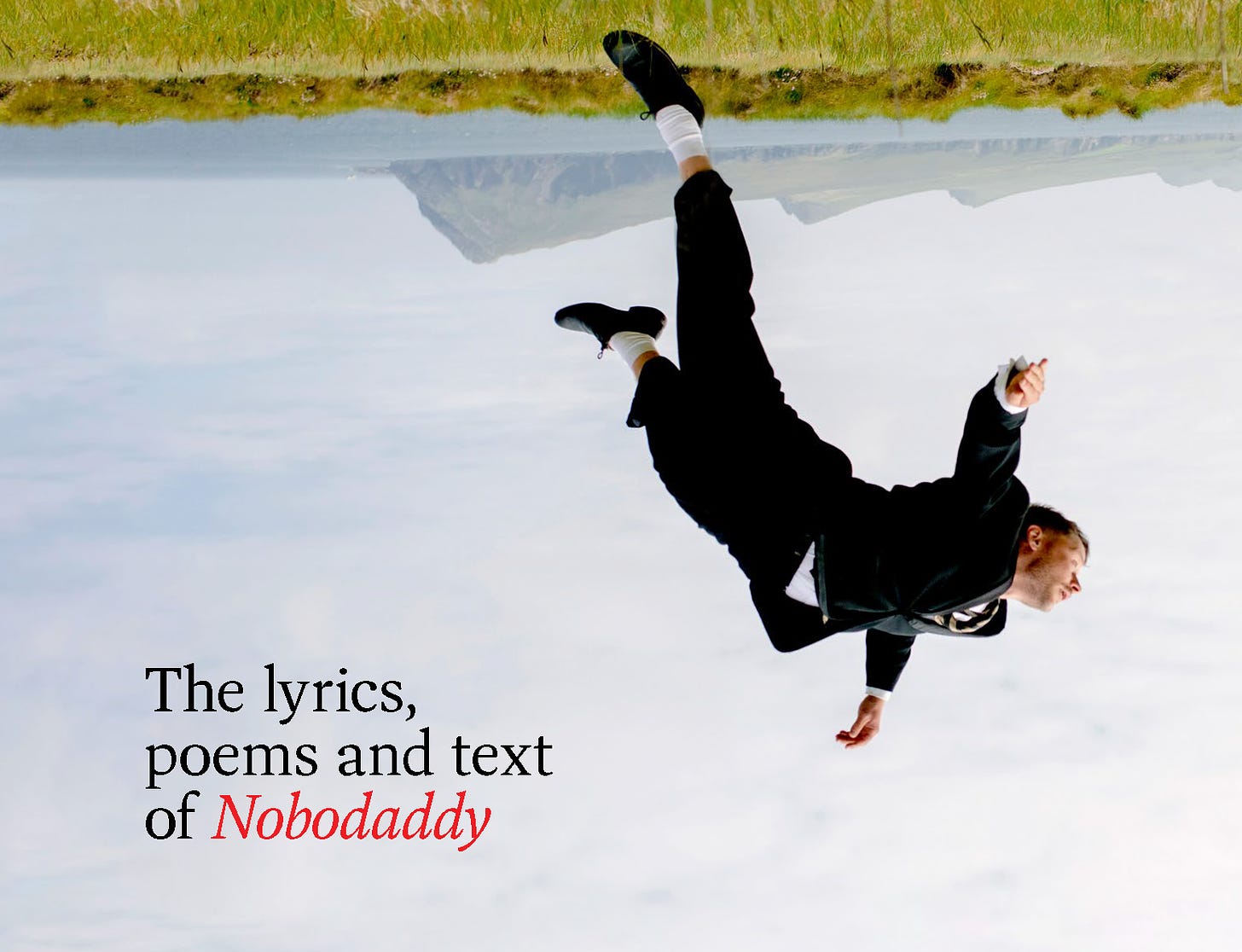

There isn’t enough backstory in Blake’s Nobodaddy to support an extended narrative in performance. Instead, the audience is drawn into a sequence of dramas, showdowns, trials and agitations, knit together by the show’s extraordinary music. While narrative ticks link the scenes, the effect as a whole is not of a story unfolding but of a compressed, synchronic representation of all of Irish trauma into one, extended image, as if the Island itself were having its troubled history (aka the English) flash before its eyes in a series of hi-definition, hi-speed masques. The show’s subtitle, Tríd an gpoll gan bun, translates as ‘through a bottomless hole’ – the feeling of falling endlessly into which may very well be part of the phenomenology of being a victim of the insatiable appetite of racism and Empire.

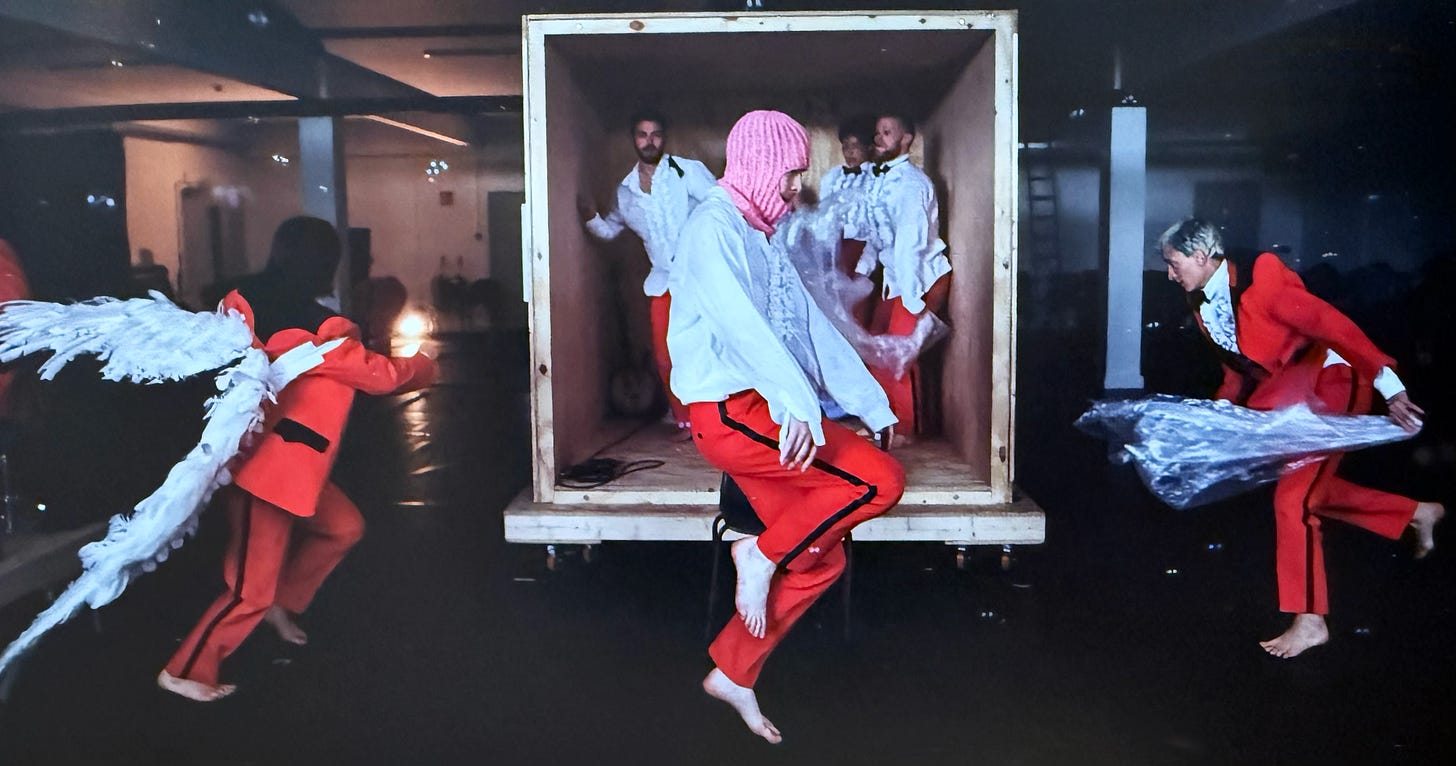

The famine of 1842 is referenced, and the 1975 ambush and murder of members of the Miami Showband – killed in part for their non-sectarian appeal as the chart-topping ‘Irish Beatles’ – comes as close as we’ll get to finding a moral core to the performance; Keegan-Dolan has talked in interview about the impact of the killings on his mother in particular. Several dancers wear balaclavas, invoking the paramilitaries of old – or perhaps, to a younger audience, Irish hip-hop trio, Kneecap. The hero’s absurd dreamscapes in Finnegans Wake may be in play here too: some of the balaclavas have rabbit ears.

Music is at the heart of Nobodaddy, with folk artist (and sometime Bill Frisell collaborator) Sam Amidon and band providing the backbone of the performance, based on Amidon’s own material and traditional Irish and Appalachian songs – several of which, including the key tune, Lily-O, appear on Amidon’s album of the same name – along with more of Blake’s poetry, a Wesley hymn, and a tribute to the Miami Showband.3 Such material may be unfamilliar to some of the audience (give or take Abidon’s arrangement of Ireland’s winning entry in the 1970 Eurovision Song Contest – Dana’s All Kinds of Everything) but the music sounded authentic to these ears, schooled in The Carter Family, Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music and ‘the high lonesome sound’ of Appalachian country music. And even if you were to insist that it can’t be authentic (‘cultural appropriation’), then these are certainly at least real channellings of the originals rather than fuzzy-felt folk-by-numbers.

The danger with using song structures as a framework is that the pacing is tied to the change-over rhythm of alternating tunes, and you end up with a musical. Nobodaddy wires around this by the use of live industrial and electronic soundscaping mixed by Sandra Ní Mathúna, which helps shake up the marching pace of the jukebox and allows the dance to achieve its own, unique, overarching rhythm.

The story opens with what looks like the mangled body of an angel stretched out on the floor as two cleaners (or nightwatchmen) stand idly by chatting, occasionally launching desultory attempts at tidying up. They can’t lift the angel, for some reason. Suddenly, the angel, awakening, swoops up and out, and the dance begins (Klee’s angel of history on the move?). The dancing is as abstract as the framing story: apart from a handful of key parts played by the company leads, the dancers, dressed uniformly in grey and red (Redcoats?), come across as androgynous, and as interchangeable cyphers, perhaps just parts of a greater dancer, history itself, in relation to which they are helpless puppets – or active limbs.

The players swoop and collide like crashing waves, or flitter and twitch about the stage, all jelly arms and gyrations, as the music and dance teams wash through each other, separating, then merging again in new permutations. These pulses within the dance, following a subterranean logic of their own, and accompanied by Amidon and the band, go on for one and a half hours without a break. It is easy to feel overwhelmed.

For the full effect, you might want to read all the programme notes before entering the theatre. Perhaps that is a weakness of the show. But in the absence of that, the energy levels on stage are enough anyway to draw you magnetically to them, even if the work of figuring out what was being represented is postponed until you’ve emerged from the show’s cocoon of enthrallment at the show’s end.

Streaming out of Sadler’s Wells onto the streets of Islington at the show’s end I overheard a few people saying they had no idea what they’d just seen… but no one looked any the worse for it. And isn’t that how art works, slipping its effects past the threshold of our comprehension? The sense of being overwhelmed by the show is quite deliberate anyway, coming from a choreographer who works to avoid the situation in which “thinking [takes] over and we… cease to have a complete experience,” and for whom Blake provides “tools to validate an approach that avoids that thinking matrix”.4

The show is not about Nobodaddy at all, but about his victims – in this case, Ireland and its people. Nobodaddy is just the fulcrum around which all these events turn.

It seems an appropriate tribute to the god of slaughter to lay out the suffering he has caused as a bloody offering at his feet, a warped tribute in the form of combined defiance and an appeal to something beyond Nobodaddy’s power, revealed in the telling itself: namely, the protagonists’ commitment to (in Blake’s terms) Golgonooza, the city of imagination, the construction of which is the point of art, as art, in turn, forms the imaginative foundation of real politics, real communion. There is your alternative to Empire.

It has been a longstanding vexation that whenever Blake is thought of in connection with music, it is assumed that the model is that of the simple melodies and clear intonation of English hymnals and children’s songs, whereas his poetry and visual art boldly encompass complexity, contradiction and dissonance. Who is to say that an appropriately Blakean music would be any different? One understated triumph of this production is that it brings the world of Blakean music into contact with the wholly appropriate domain of the complexity, polyphony, distorted, trilling spectrality of actual folk music. In that respect, Nobodaddy: Tríd an bpoll gan bun is a bit of a coming-out party.

The great bubble-storm at the end of the evening acted like a hand wiping away the chaos we’d seen unfold, removing us safely from it, soothing us and leaving us with thoughts of the Imperial brutality we’d seen, which Blake so despised, and of the Irish people, for whom that violence is a nightmare from which they are still trying to awake.

See teacdamsa.com/about.

William Blake, ‘To Nobodaddy’, ‘Let the Brothels of Paris Be Opened’, and ‘When Klopstock England Defied’, in Blake’s Notebook (c. 1987-1818), aka the Rossetti Manuscript, in William Blake, David Erdman (ed), Harold Bloom (commentary), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), Anchor Books / Random House, 1988, pp471, 499, 500.

For more information about the evening’s music, see Amidon’s online notes for the show.

Michael Keegan-Dolan, in Stephen Pritchard, ‘Nobodaddy – an interview with Michael Keegan-Dolan’, The Blake Society, blakesociety.org, 2024-11-18, accessed 2024-12-01.