Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead

A review of the Complicité production, based on the Blakean 'eco-thriller' by Olga Tokarczuk, at The Barbican, London, March 2023. First published in Vala, the journal of The Blake Society.

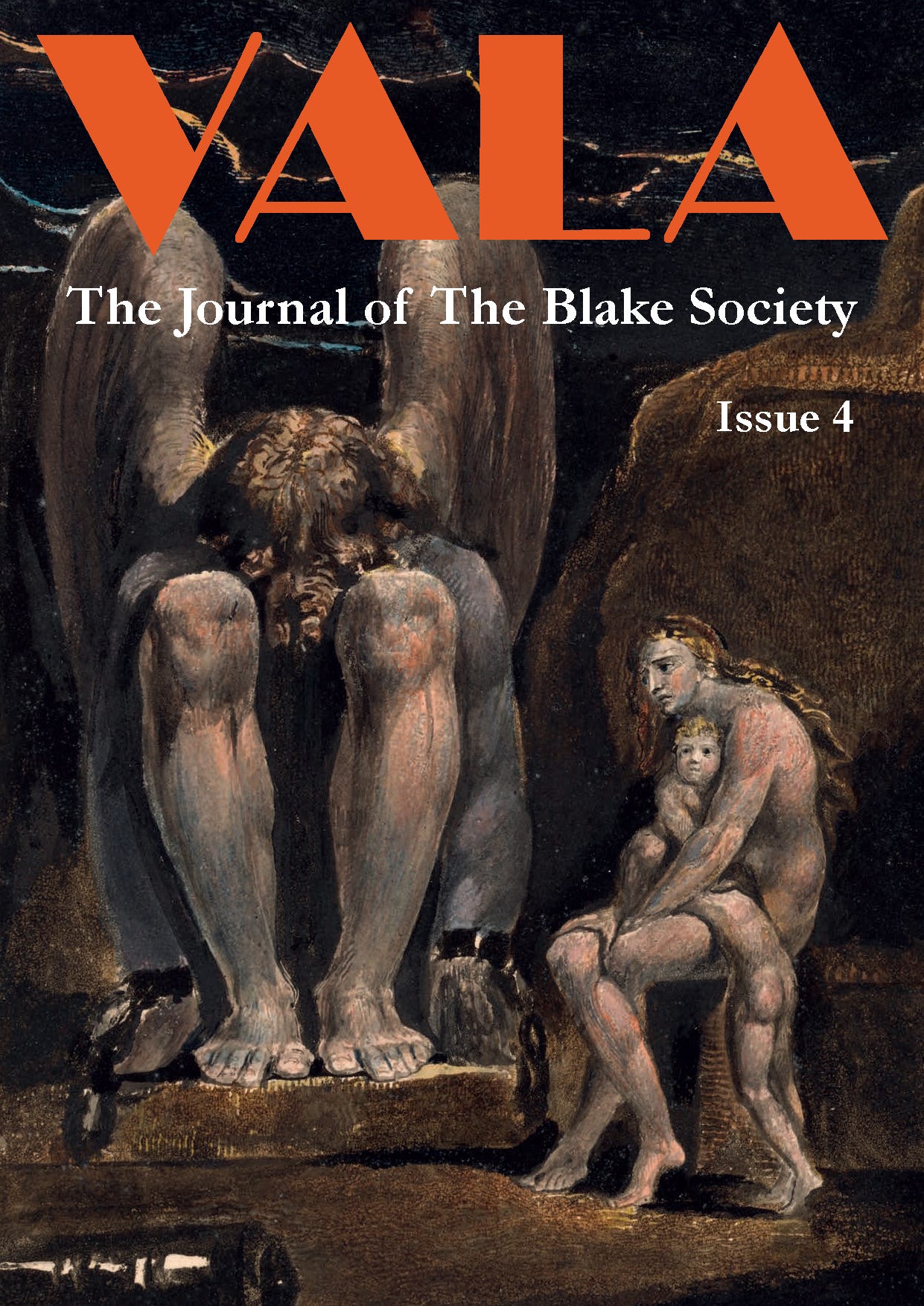

This review first appeared in Vala #4, Winter 2023, the journal of The Blake Society. Download Vala #4 here.

A Horse misused upon the Road

Calls to Heaven for Human blood

William Blake, ‘Auguries of Innocence’ 11-12

Anger is not a bad energy

Olga Tokarczuk

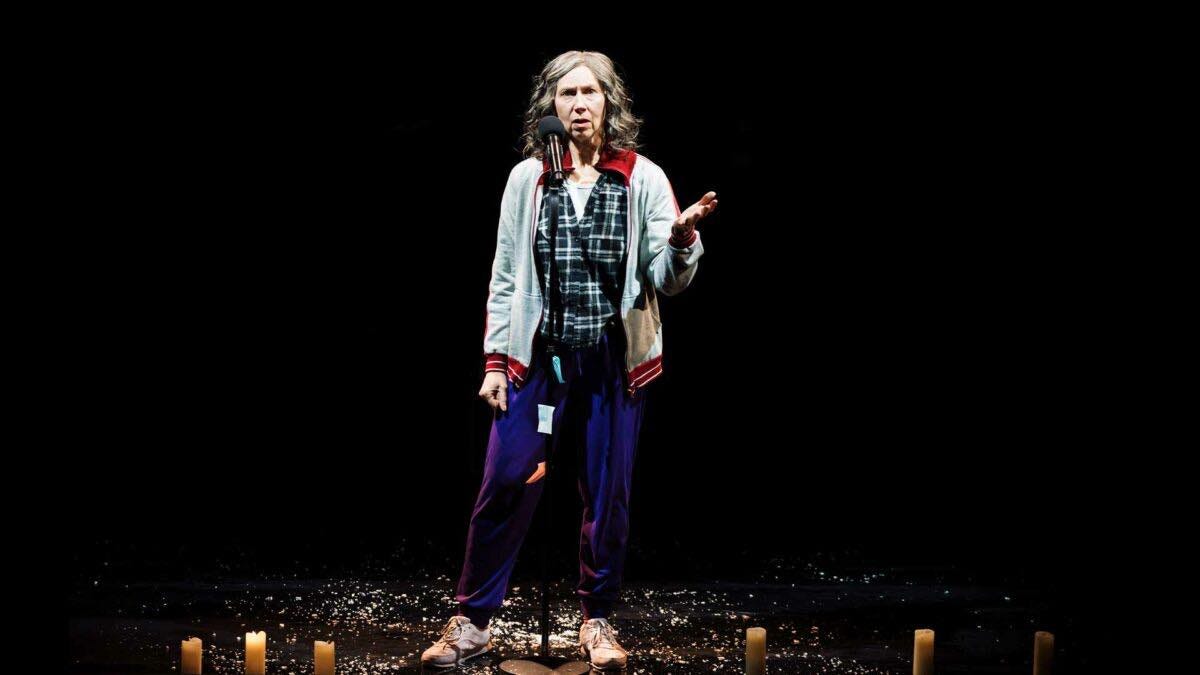

In crumpled leisurewear, clutching her ever-present carrier bag full of who-knows-what, senior citizen Janina Duszejko opens the show with one of her rambling speeches. Janina frets about her ‘ailments’, about her missing dogs, and about the state of the world in general. She is particularly worried by the happenings in her own little community in the Kłodzko valley and plateau, on the border between Poland and Czechoslovakia.

Janina’s opening monologue is the cell which the rest of the story reworks in a series of memorable permutations. It captures from the start the dilemma we confront in appreciating Janina: on the one hand, she witters on about astrological charts and planetary alignments: “He generally doesn't say much. He must have Mercury in a reticent sign”; on the other hand, she is full of a great depth of feeling, and many wry and clever insights into human nature. She is also aware of a fact with which she continually confronts her audience: women like her are not taken seriously. “Nobody remembers old biddies like me.” How seriously should we take Janina?

Janina lives in semi-retirement in a remote cottage in the valley. Once a civil engineer, she’s now a part-time schoolteacher and a caretaker for a number of summer cottages. When not itemising the trials imposed by her aches and pains, she spends her time keeping an eye on the valley and helping her friend, Dizzy (Alexander Uzoka), translate Blake into Polish. The fixed points of her life are the works of Blake and her astrological charts, both of which she refers to incessantly.

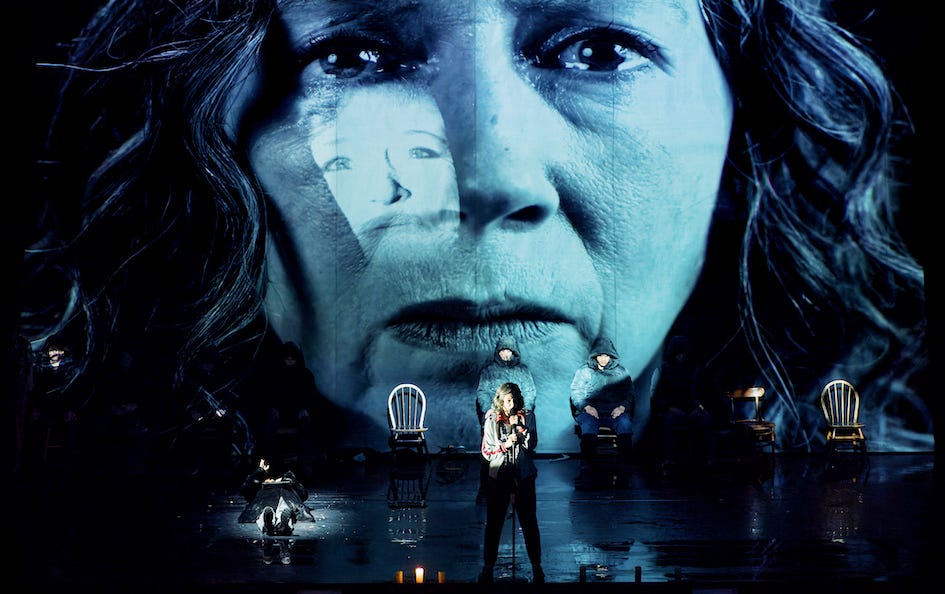

The audience was still waiting for showtime when Amanda Hadingue, as Janina (triumphant as a stand-in for sick Kathryn Hunter), shuffled onstage and began to speak. I thought we were to be reminded of the Barbican’s safety procedures and exit routes. Instead, we were dropped into the heart of things, since Amanda-as-Janina started telling us about how her neighbour, Oddball (César Sarachu), had found the body of Big Foot the poacher (like God naming the animals, Janina gives all of her acquaintances a tag to suit them). With no curtains up or fanfare to prepare us, we are ensnared in Janina’s casual, intimate obsessions from the start.

Once we are done hearing about her Valerian pills and the state of her feet, it turns out that Janina is preoccupied with a spate of mysterious deaths in Kłodzko Valley. First to die is Big Foot, choking on a deer bone. Next, the Police Commandant is discovered by Janina and Dizzy, his head battered, fallen down an old well. The owner of a local fox farm turns up months later, his body almost completely decomposed, hidden in the woods. The village President turns up dead on the morning after the Mushroom Pickers’ Ball, riddled with the larvae of an obscure beetle. And then there is the mysterious fire at the church on St Hubert’s feast day, caused by magpies, which kills Father Rustle.

Janina’s reading of Blake leads her to conclude that as all the victims were involved in the mistreatment of animals, they must therefore be the victims of an animal uprising. She believes the deer conspired to thrust the bone down Big Foot’s throat in return for his snaring one of their group, and that another herd ganged up on the Commandant to nudge him down the well. The animals want revenge.

When the police give up investigating the murders due to a lack of evidence, Janina pesters them, writing them letters outlining her theory, providing examples from history where animals have been put on trial and found guilty, suggesting that they are culpable here too, and demanding that the police take action. Everyone ignores her, of course. Janina is Miss Marple cast as an aged hippie Hunt Saboteur.

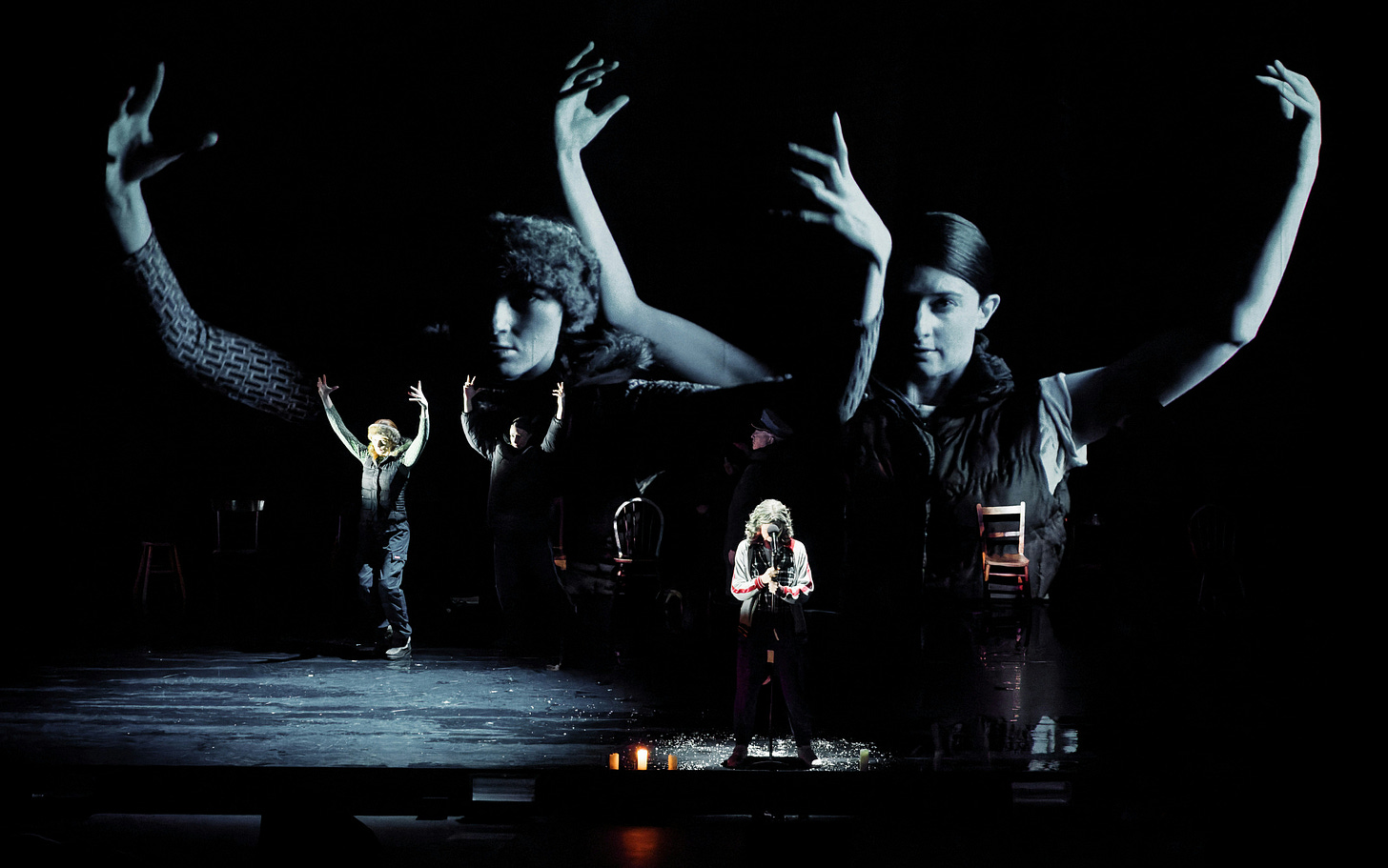

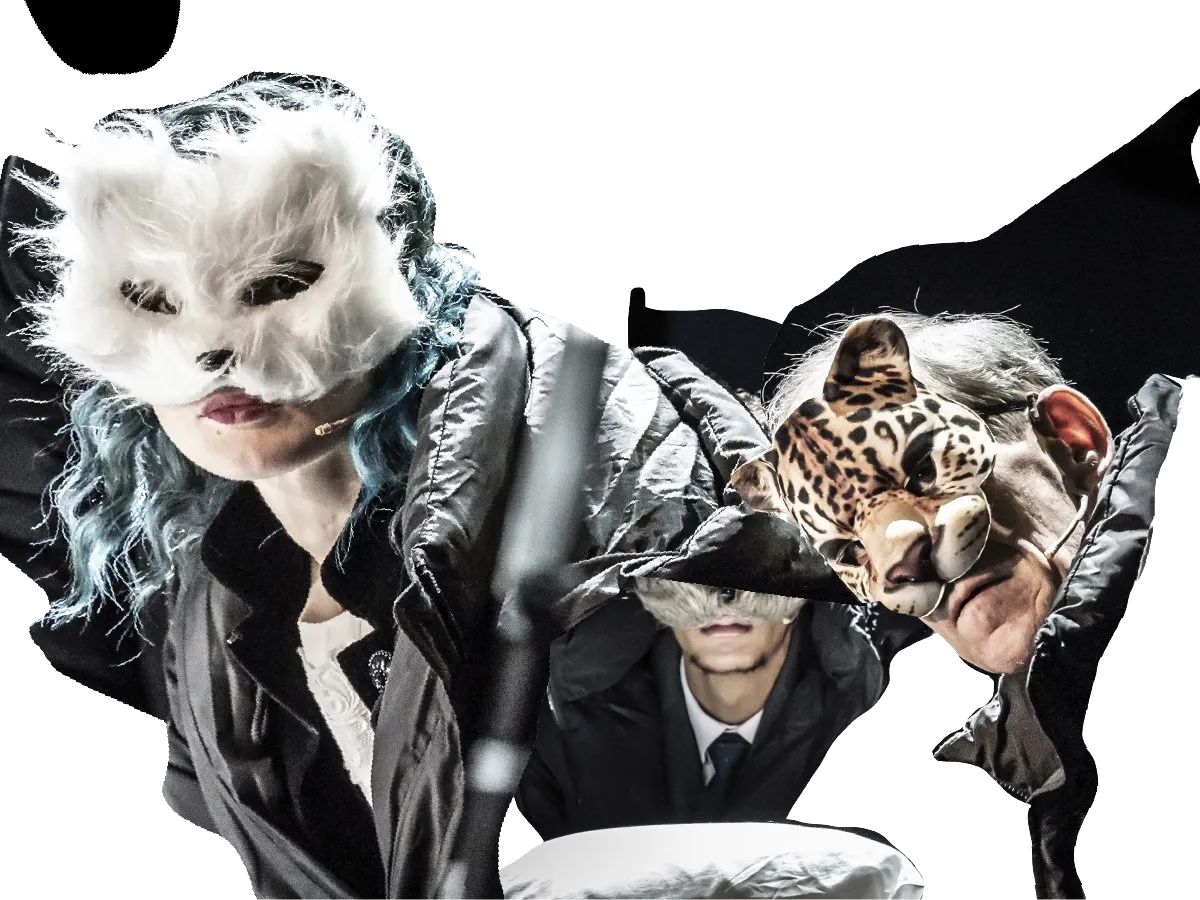

In this thrilling production, the quandary at the heart of Tokarczuk’s novel is more vividly presented than in either the novel itself or the film adaptation, Spoor. Janina’s monologues are literally front and centre stage, with occasional breaks for dialogue with her friends and neighbours, while the quotes from Blake, images of the suffering of the animals, and the banality and complicity of the citizens of Kłodzko are all cleverly relayed through projections and scenes and sounds happening off-stage or in the background. Complicité do some of the work imposed on the reader when reading the novel, untangling overlapping layers of reality, allowing us to think them through, while keeping everything neatly wrapped up by Janina’s chatter. The shocking and vivid nature of some of these accompaniments to Janina reflect the brutal realities which inform her imaginings. The production also underlines the totalising vision of the novel, with actors taking multiple roles and even becoming animals. Everything is connected.

But there’s a sense in which the central character here is actually William Blake, whose thoughts are never far from Janina’s mind in either the original novel or this Complicité production. Blake provides the title of the work, of course, while quotes from his Auguries of Innocence head each chapter of the novel, and pepper this performance.

Blake, in Tokarczuk’s hands, is the Keyser Söze of Kłodzko Valley. Everything he has to say is laid out for all to see, nothing is concealed — yet he somehow passes among us almost without recognition, because he is not what he seems. It is only with the plot twist that the truth dawns on us, and Blake’s import really hits home, when we see the consequences of the identification with animal life he has inspired in Janina. We register the quotes and references when we see them on stage, but culturally we are conditioned into seeing Blake as representing (ironically, given his Cockney reputation) an arcadian ideal, used to prop up images of a happier, older world, so we barely register what he’s saying other than as some sort of ambient good-naturedness, as it has all already been turned into a tiresome sack of clichés by this reckoning. Blake has become a harmless spirit, tamed by the culture industry. Our minds move over the quotes without fully absorbing them… until events at the end force us to look again, and we notice as if for the first time their incendiary intent.

A dog starv’d at his Master’s Gate

Predicts the ruin of the State

William Blake, ‘Auguries of Innocence’ 9-10.

Just as we misread Blake when we see in him only rustic joy and innocence, so we mistake the Blakean mood as one of satisfied Romantic immersion in nature. Tokarczuk successfully welds together the constant misogyny Janina endures and the appalling suffering of the animals — itself echoing the holocaust which happened in the same region within living memory — into a single image of evil after the Fall, which Janina confronts in the story, and which the book itself is directed against, in the context of a Poland shifting increasingly toward authoritarianism. The sense of this unitary evil, including the desolation of nature, pervades the book and the stage production alike. While there is much of wonder in Janina and her friends, there is also a darkness to their situation that no invocation of Arcadia can dispel, the darkness of our times.

Tokarczuk’s extraordinary novel was notable for the way its militant reading of Blake stood out from the ranks of milquetoast Blakeanism. And we do need to be reminded of what Joyce said of Blake, that “his spiritual rebellion against the powers of this world was not made of the kind of gunpowder, soluble in water, to which we are more or less accustomed.” Complicité’s team understand the thread of Tokarzuk’s interpretation, its’ radical heart, and have brought it vividly to life in this stirring call to activism.