From Hyperobjects to Re-Animism: Titans at the End of the World

Living the reanimated life in a time of mass extinction. The advent of climate collapse creates an uncanny world in which Titans awaken.

A high enough dimensional being could see global warming itself as a static object. What horrifyingly complex tentacles would such an entity have?

Timothy Morton1

The surface biosphere has never been separate from the cthulhoid architecture of the nether.

Reza Negarestani2

Recent weeks have provided plenty of moments when global warming seemed suddenly as plain as the nose on your sunburned, peeling face. Yet the world limped on as though nothing much had changed, rather than potentially everything. We seem doomed to end up burning or drowning in a vast deluge-conflagration while raising not much more than a whimper and a lot of hot air.

A thousand fires burned across Canada and the West Coast of America last month; 300 more burned in Greece as gale force winds combined with unusually hot, dry weather; other fires lit Rhodes, Corfu, Athens, Calabria, Palermo, Sicily, La Palma, Gran Canaria, Bitsch (Switzerland), Hatay, Mersin, Canakkale provinces (Turkey), Anatalya, Lisbon, Sibenik & Grebastika (Croatia), Cagnes-sur-Mer, Shaidurikha (Russia), Latakia (Syria), Skikda, Jijel, Bouira, Bejaia, Tebassa, Medea, Setif and El Tarf (Algeria), and Tabarka (Tunisia); neon-glowing clouds of hot smoke engulfed North East America while Central and Southern Europe baked.

On the East coast of America, several hurricanes formed off the Gulf, with Hurricane Idalia causing chaos and mass evacuations in Georgia; meanwhile, three Pacific typhoons made land in China, inundating Hebei and Beijing with more rain quicker than at any time in a previous century and a half of records, with villages destroyed and thousands displaced. The number of annual floods in China has increased more than tenfold in less than a decade – in 2011 there were an average of seven floods a month, while this year saw 130 floods in July and 82 in August. Meanwhile, millions are starving due to a megadrought in East Africa., the worst for at least 40 years, affecting 50 million people and threatening almost half of those with famine.

The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.

António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations3

When everything heats up, there is more energy in the system: water evaporates faster, winds blow more forcefully, fires burn more intensely, and we feel the consequences more keenly. Not only does climate become more destructive, but its effects start to combine and multiply; there are more fires because of the increased heat, but stronger winds now also spread them more rapidly. More heat causes more rapid evaporation of water, producing more rain and flooding.

Storms and flooding gnaw away at resources and infrastructure just as they are needed to combat other effects of the carbon fuel plague. People’s lives are ruined, so they become refugees among their neighbours, putting strain on those economies in turn. Crops are destroyed, incomes fall, and no one can now pay for adequate weather defences. One problem feeds the other. Complex interactions create feedback loops amplifying the effects of change. Misfortune accelerates.

Adding to the confusion, the chaotic nature of global weather means it is often impossible to predict precisely when particular tipping points will happen, even when we know they are due. The Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation (AMOC) governs a great part of our local weather systems by channelling heat (in the form of hot water) from the equator to the north, warming Europe to the East, while directing cooler Arctic waters down south to the West. The entire direction of this current is due to reverse, dramatically changing weather systems on either side of the Atlantic and inevitably causing entire ecosystems to collapse – but we don’t know whether that will happen next year, in five years, fifty years, or more. How do we cope psychically with this novel combination of disaster, inevitability, uncertainty?

This could be the point at which people wake to smell the burning coffee plantation. You imagine people finally confronting the ‘naked lunch’, “the frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork."4 Instead, we anaesthetise ourselves against what is happening even as it enrages and alarms us. We fret and prevaricate.

There is no way to process all of these events and respond appropriately. There is no way to know that our response, whatever it is, is right. There is no way definitively to say who or what is ultimately responsible, even though it also seems clear immediately who is largely to blame. We play dead while jabbering on. We grieve.

You can see how this possum act works in a fight between predator and prey. When fight and flight have been exhausted, it makes sense for the prey to roll over on its back, its toes in the air, hoping the predator is confused long enough to provide one last chance to bolt. But we are not the prey here, and there are now no chances of escape; we are simply awakening inside a cauldron of our own making. 80% of recorded animal extinctions in the last half a millennium took place after 1900. We are living through a mass extinction event. The land those animals grazed is now burning, or drowning. Playing dead doesn’t work when you have your foot caught in the railway tracks while a fully loaded freight train descends on you.

Hyperobjects and the new Wyrd

We knew by the mid-1990s that lurking in the tails of our climate model projections were monsters.

Bill Hare5

Yo pretty ladies around the world

Got a Wyrd thing to show you,

So tell all the boys and girls.

Do your dance, do your dance quick

Come on baby tell me what's the Wyrd.

Wyrd up.

Cameo

Most annoyingly of all, you already know all this. You‘ve watched the weather bulletins; you’ve read the statistics, you’ve seen the graphs of accumulating CO² levels and rising temperatures; you know all about the untimeliness and timidity of the global political and industrial response, and you have been subject to endless exhortations to donate and to act and to purchase. It is exhausting to know all this and still not know what to actually do.

The ‘shock of the new’ was once thought to deliver a salutary wake-up call, but the new climate regime doesn’t work that way, and the effect on civilians today is like the stupefaction that was the aim of the ‘shock and awe’ strategy used in Iraq, intended precisely to paralyse the enemy’s will to resist.6 The images of that war anticipated those of recent weather reports. The impact is similar. The military understands this already, and now speaks of war as a hyperobject, and new ‘hyperthreats to be contained’.

What is the new psychic state induced by climate warming? The clearest answers may be coming from those such as Timothy Morton who explore the ontology and phenomenology of hyperobjects. A hyperobject is not fundamentally different from any other object, but its size compared to ourselves (in terms of its physical size and its duration), is such that it confounds the consciousness we have been developing at least since the invention of agriculture. Examples of hyperobjects include the global weather system in toto, global warming in particular, radioactive pollution, capitalism, microplastics in the environment, oil, the Anthropocene, and so on. All these objects are distributed in time and space in a way that makes them opaque to the human mind – or completely transparent – even when we have supercomputers to calculate their features and trajectory with some precision. But all that data does not add up to a single intuition. And as the data piles up, we are assailed on all sides by this wyrdness.

Global warming causes the fires we see on the news, but this ‘causing’ is more mysterious than people assume. As any climate sceptic will show you, there can be no proof that global warming caused this or that particular fire or hurricane. We know that global warming increases the incidence and severity of forest fires, but we can’t prove that it caused any particular fire. That doesn’t mean the climate sceptics are right – they simply exploit the fact that most people don’t know how causality often works in mysterious ways. People think science is about absolute certainty, unambiguous data and unconditional judgements. No actual science is like that, and certainly not the science of climate change. Climate sceptics use this misconception as a jemmy in their existential struggle to keep syphoning profits from the fossil economy. Still, isn’t it odd to be brutally stricken by a force you can’t prove is in play at any given moment?

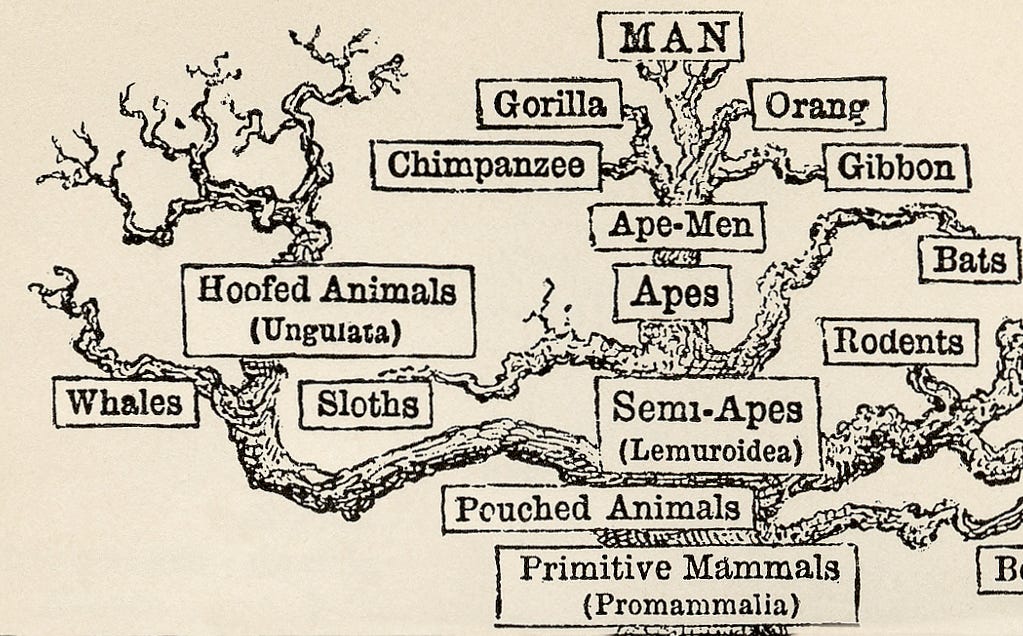

Climate warming awakens us to the death of human domination, not only in the obvious sense of exposing the inability of human power to prevent runaway warming – that is now a matter of record – but more fundamentally in terms of undoing the domination of mind over matter, and its hierarchies such as the Great Chain of Being, which sees humanity at the peak of creation. The divine-human mind is imagined to rule a Nature defined in opposition to it. And while mind is rarely imagined to be omnipotent, it approaches omnipotence through the multiplicative power of its prosthetic technologies. Culture itself is an autonomous prosthetic technology of the spirit that drives us on in our assault on things.

This mental world of neo-Mesopotamian man is being spectacularly undone by global warming. Long before any apocalypse takes place, global warming quietly ushers in the end of the world. The world ends in the sense that the polarising hierarchical, exclusionary mental world of the neo-Mesopotamian Human crumbles on contact with global warming, pushing us toward a different conception and vision. We are not allowed to get too excited about this since the new perspective also undermines the linear historical thinking that produced Joachim of Fiore, the Ranters and the Hussites and their talk of the revolutionary overthrow of the old order. Nevertheless, the New Testament book of the apocalypse emphasises in its very title that this ἀποκάλυψις (apokalypsis) is essentially an 'unveiling' or 'revelation' of just this kind; a world-shattering head-f*ck.

Global warming makes us aware of the viscosity and stickiness of the hyperobject; it can’t be avoided. It gets everywhere – there is no escaping it. Our cells are irradiated, our lungs are poisoned, and our organs are full of microplastics. There is no opting out, even for Elon Musk, whatever his dream of ‘blue skies on Mars’.

But as we have already seen, at the same time as being all-engrossingly sticky, global warming is also mysteriously remote and somehow, somewhat absent. It is here, there and everywhere… but you can’t put your finger on it, and it is nowhere exactly to be found. We feel the hot air on our cheeks manifesting it, but we never feel global warming itself. We can’t touch climate change even while up to our necks in it. Global warming, as a hyperobject, works instead interobjectively; its effects are mediated aesthetically by other objects that exist in overlapping sets and networks within the hyperobject – not unlike the “oceans of Buddhas” of the Avatamsaka Sutra, mentioned below. Global warming is real, not merely an extrapolation from computer models, hyperobjects are “not just collections, systems, or assemblages of other objects. They are objects in their own right”,7 but this objectivity in many cases is tantalisingly distant even when it is upon us, and we stick to it.

Hyperobjects have a different temporality to our own. They operate on larger scales of time than are easily grasped by us. We don’t see how odd it is that the North Sea today has “no great whales, vast shoals of bluefish, two-metre cod and halibut the size of doors”,8 because the extinction took place slowly and over a long time. It was there every day, unnoticed. From one generation to the next, we don’t see the depletion of Nature because we don’t understand that our starting point in making any comparison is already seriously degraded. The temporality of the hyperobject is too great for the human mind to parse as such, gulped down in a single gestalt. The temporality of the hyperobject subsumes the temporality of humans. A single human lifetime is not enough to register the impact of global warming to the extent to which it impacts human life. We lack the shape and mass necessary to resonate in tune with the pulse and vibrations of the hyperobject: to achieve this requires retuning.

As well as being vast, the temporality of the hyperobject may be many and various. Different faces of global warming appear at different rates. Of the main types of radioactive pollution, strontium-90 and cesium-137 have half-lives of about 30 years, while plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,000 years. The implications for future generations and the process of calculating and appraising the effects are very different for these distinct forms of pollution; “We are dealing with an object that is not only massively distributed, but that also has different amortization rates for different parts of itself.”9

Plastic People

The historic moment at which hyperobjects become visible by humans has arrived. This visibility changes everything.

Timothy Morton10

Me see a neon moon above

I searched for years I found no love

I'm sure that love will never be

A product of plasticity

Frank Zappa, Plastic People

I felt like an active life form, tendrilled and strange

Amanda Gefter11

In Morton’s terms, the effect of the human experience of environmental hyperobjectivity is to render us lame, weak and hypocritical. We are made weak because we realise our helplessness in the face of the hyperobject. We know we are lame when we see that objects always necessarily withhold part of themselves from us. They are always opaque to us. This was always true of all objects, it is simply that experience of the global warming hyperobject makes it a readily apparent feature of everyday life.

Having abandoned the transcendental pole of meta-language that has long propped up the human, we become hypocrites since our every action is problematised: “Inside the hyperobject, we are always in the wrong.”12 We cannot ever possess the certainty that propels the ideologues of Enlightenment and bogus ‘secularism’ today. The world becomes unreliable as our inner life is distorted in relation to it: romantic interiority becomes the void of inwardness we discover when we realise that we ourselves are withdrawn and not entirely available even to ourselves – though, as Morton points out, “it is not an unpleasant reversal unless you really need to be on top all the time.”13

Hyperobjectivity is relative. One object is a hyperobject with respect to another based on its relative size and duration. We ourselves are hyperobjects in relation to other beings and other objects. We may even be hyperobjects to ourselves – the Ship of Theseus moving in mysterious ways from the point of view of the planks and oars it encompasses. The wyrdness of global warming is the same wyrdness we manifest to others, just as they manifest it towards us; it is simply that global warming is making us aware of the inherent uncanniness of everything as it slips from our hands.

Squares in Flatland

The phase-space of global warming is at least one dimension greater than ours. What looks so strange to us seems like a regular object to a 3+-dimensional observer. The strangeness of the hyperobject manfests only because we experience it from a lower-dimensional perspective. The 2D world of Flatland, in Edward Abbott’s 1884 book of that name, was designed to illustrate the strange properties of 3D objects as they interacted with the world of the Flatlanders, hoping thereby to explain 3+-dimensional objects in relation to our 3-dimensional world by analogy.

A sphere appears in Flatland first of all as an inexplicable eruption which grows into an ellipse, continuing to expand awhile before suddenly reversing and starting to contract; finally, the ellipse shrinks into a one-dimensional point before disappearing forever down the gullet of a singularity. From the point of view of 3D space, a sphere simply fell through a plane: from the point of view of the Flatlanders, something burst incomprehensibly from out of nowhere, then expanded using (what passes in Flatland for) ‘energy’ seemingly from nowhere, before being utterly annihilated. Uncanny.

The geometry of Flatland was used by Victorian mystics and table-tappers to describe their communication with spirits, which they thought of as higher-dimensional beings whose elusiveness and strangeness generally was only apparent to those of us trapped in lower dimensions. Global warming inaugurates the age of universal strangeness in which everything is wyrded out in this way, and the table-tappers’ spirits return in legions to roost.

Realisation and acceptance of this new opacity and wyrdness usually only arrives after a stage of grieving for the world that has now ended. What form this grieving takes probably depends on how you were embedded in the old world to begin with. For those like me, this takes the form of grieving for the broadly Social Democratic consciousness of progress and creeping freedom underpinning everything – the idea that, no matter how bad things are, we could make them better through organisation and rational planning, or through the ultimate ‘new perspective’, social revolution. This idea is one of the first victims of global warming, leaving generations bereft and frantic. Not that we don’t need change. Far from it.

It is easier to move beyond this world when you realise that the wyrdness that beckons is just other beings. It was always so, and it is only us that have changed, now that we are being baked. And in some ways this ‘wyrdness that beckons’ should be familiar, as it was part of our existence before the Anthropocene and the rise of thanatological culture.

Return of the Titans

And from Typhoeus come boisterous winds which blow damply, except Notus and Boreas and clear Zephyr. These are a god-sent kind, and a great blessing to men; but the others blow fitfully upon the seas... Others again over the boundless, flowering earth spoil the fair fields of men who dwell below, filling them with dust and cruel uproar.

Hesiod14

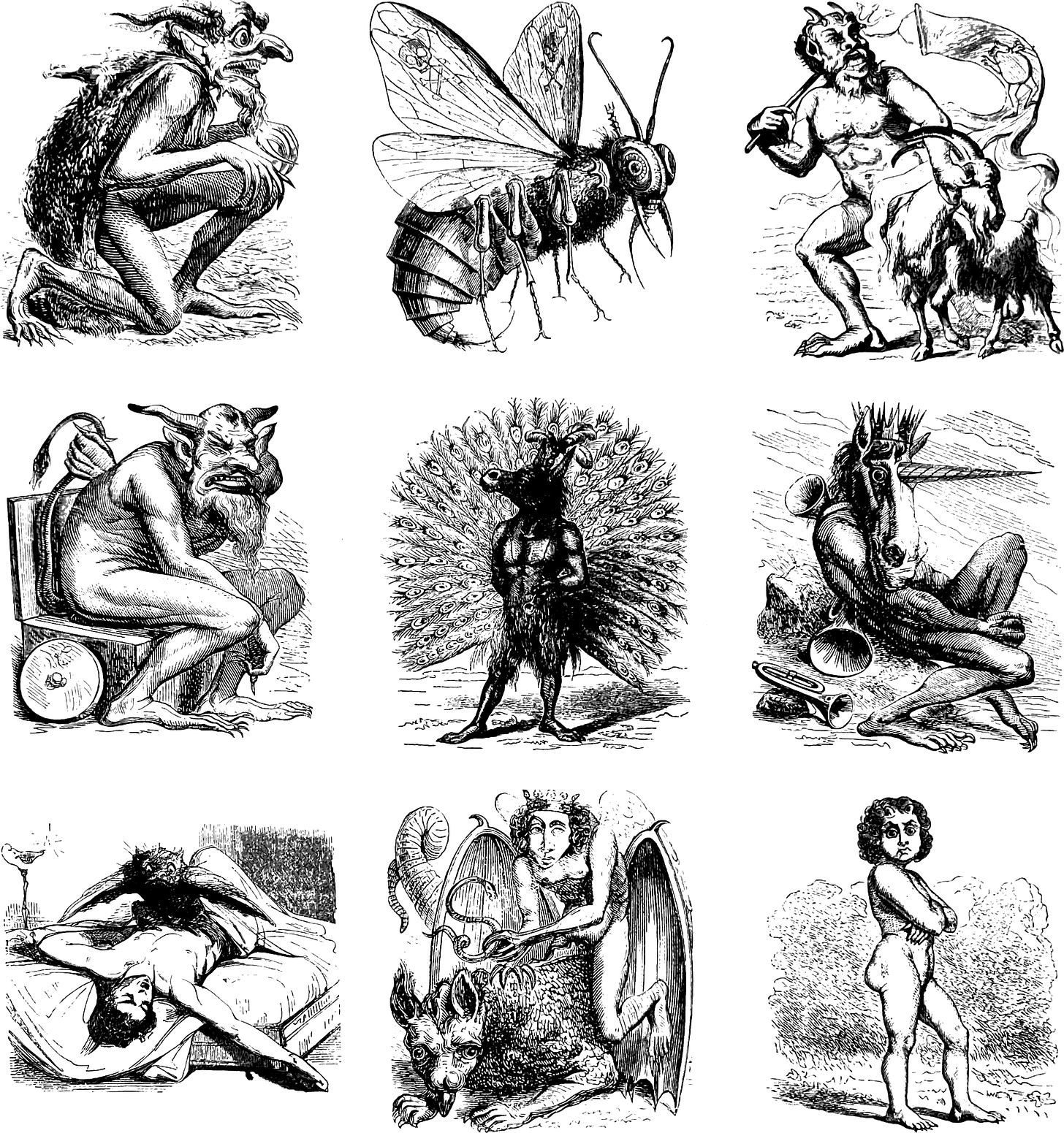

One of the oldest myths known to mankind tells the story of the human conquest of nature that ushers in the Anthropocene and the Age of Asymmetry between human and non-human. The dragons and Titans of this myth embody the disorder of nature that must be conquered for human culture as we know it to exist. The Titans back then were chained and put to sleep, but are now awakening thanks to global warming. The core myth concerns a serpent, or dragon, embodying the chaos that must be subdued for the world to exist. The dragon must be defeated in order for the world to begin.

Julien d’Huy claims to have traced the myth back to before humans left Africa, though others hotly dispute this.15 Whenever it originated, and whether the idea reproduced itself unprompted in different cultures around the world – as if the mind spontaneously reached for the same symbols when thinking about the same matters – rather than spreading through cultural diffusion, the fact is that diverse cultures globally, from Africa and China to America and Australia, share the myth of a snake (dragon), connected with water, who is often a female who can also fly through the air, and spells trouble.

The root versions of the myth are those in which the dragon, representing the primordial chaos of the universe, is defeated in a cosmic war with its own children, who thereby clear a space within the chaos and inaugurate the world we live in, much as Babylonian priests conceived of Marduk’s defeat of the sea monster, Tiamat, in the Enuma Elish. Later, derivative versions of the myth – the tale of Cadmus and the Dragon, for example, or St George and the Dragon – may tone down the cosmogenesis, recasting it as a battle to make the city safe, but the core of the myth concerns the creation and management of a world. The story of Eve and the serpent in Genesis clearly derives from some such myth.

Other variations and echoes of the myth take the same cosmogenetic story but recast the dragon. In Greek mythology, the Titans ("the former Gods", theoi proteroi, according to Homer) precede the familiar Olympian gods, and represent the forces of existence, originally locked up by Uranus in the womb of Gaia, and put to flight in a war with their own children: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Hades, Hesta, and Chiron. The latter are the light-giving forces that bring order to the world, as with Marduk’s army of gods that fought Tiamat, or the Norse Aesir in their war on the Vanir.

The conquering of chaos cannot be settled permanently. The gods maintain the order of the universe as long as they are propitiated, but they face the permanent threat of a reversal which would unleash chaos all over again. In Norse myth, Jormungandr, the World Serpent, encircles the world as Ouroboros. When Jormungandr releases its tail from its jaws he unleashes the forces of chaos previously held at bay, collapsing the balance of the cosmos and initiating Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods. Lights out.

When the Titans were defeated by Zeus they were thrown into the pit of Tartarus (as were subsequent rebels, Sisyphus, and Tantalus.) They were commonly held to be buried under mountains and volcanoes, whose eruptions channelled their power even in captivity. Appropriately enough, global warming is melting the ice that plugs many of these volcanoes with its weight, and the years ahead promise increased seismic activity and eruptions as the ice melts and Titans awake.16 The Book of Revelation tells of the powers of evil at the end of time taking the form of three monsters: the “great red dragon” (12:3), the “beast coming up out of the sea” (13:1) and the “beast coming up out of the earth” (13:11). The red dragon of chaos at the end of the world could easily be a summarised image of the elemental Titans unleashed.

The fate of the old gods in world mythology depended on tribal politics and class struggle. If ‘the former Gods’ were no longer seen as a threat by a confident ruling class, they might slowly be mythically downgraded, like a devalued currency, no longer seen as mighty rebels against the world order, buried under mountains to keep them tamed and constrained, but rather as spirits who have cheerfully departed this world to live underground, or in the seas and rivers, becoming the faeries of the lakes and hills.

This was the fate of the Fomorian gods after their defeat by the Tuath Dé Danann in Irish legend. Shakespeare knew this, which is why, borrowing from Ovid, he named the queen of the faeries Titania, ‘daughter of Titan’. According to William Blake, even the British legend of King Arthur is derived from such tales: "The giant Albion… is the Atlas of the Greeks, one of those the Greeks called Titans. The stories of Arthur are the acts of Albion, applied to a Prince of the fifth century."17 Arthur and his knights, naturally, remain sleeping under the hill of Avalon, awaiting reawakening.

In short, global warming sees us, and possibly King Arthur too, awakening in the age of Jormungandr and the Twilight of the Gods. The gods of light and order are currently folding their hands in the face of reawakened spirits, Titans, and faeries. That, at least, is one way of telling the story

The last decades of Western culture might be said to confirm this trajectory, with large numbers of people trying to tune into this reawakening of the uncanny, whether by way of the postmodern ‘incredulity toward metanarratives’; the enthusiasm for hauntology, in which the “failure of the future” leads into a culture of ghostly spectrality; the general revival of magic, the ghostly, and ‘wyrdness’, with its notion of fate that is uncanny and unpredictable; the revival of interest in folk musics, the ‘old, weird America’18; and even the enthusiasm for mycology, where mushrooms fascinate us with their liminal character, neither plant nor animal, and the suspicion that their vast underground mycelium networks are actually thinking on a hyperobjective scale in terms of size, pace and duration. I am simply listing a few Facebook friends’ hobbies here.

Having taken the mushrooms on board, it is slowly dawning on us that plants themselves have an awesome and subtle intelligence we hadn’t previously noticed. Scientists increasingly talk of plant and animal ‘intelligence’, which they define as the ability of an object to respond appropriately to its environment, but this concept is a fig leaf covering their residual resistance to the burgeoning scientific awareness of an all-prevading sentience, something like panpsychism

These developments are perhaps only straws in the wind. The first phase of hyperobjective awakening was to release the bands around the agrological mindset that got us here, starting from, at the latest, the first farms in the Fertile Crescent some 12,000 years ago. This undoing created panic among those like myself who couldn’t sense a way beyond that mindset and felt their world disappearing.

Beyond that initial awakening lies the current phase of fascination with the new wyrdness that suddenly abounds, from tutorials on postmodernism to suburban covens, obscure folk music compilations, magikal orders, pagan folk moots, mycological conventions, Psychic TV and beyond. Such inclinations had long been part of the politely seamy underside of modernism, its bohemian negative image, but were previously the hobby of initiates and esotericists; now they are blooming everywhere and are taking over your streaming services. This fascination can clearly coexist with the grief of leaving neo-Mesopotamian headspace in many ways, as a transitional consciousness. But people’s radars have started turning.

Perhaps the final stage of this journey will see us emerge into a world in which we are at home as citizens of an animate universe in which we are no longer the big bwana diks. Ironically, it was the Futurists of relatively ‘backward’ pre-WWI Italy who hymned the noise and chaos of industrial capitalism loudest when it took hold on them; while those living in the heart of the beast had already gotten over the thrill. Similarly, perhaps the fascination with the uncanny is just an early-impact, first-wave response to a new world as it kicks in, and will be replaced with a more settled posture in time.

As are the oceans of worlds and oceans of beings,

All oceans of arrangements in the cosmos,

So are the oceans of Buddhas-unbounded :

Please tell all to the children of Buddha.

Avatamsaka Sutra, ‘Appearance of the Buddha’19

To me, that settled view sounds like animism, except it is not animism seen from a Western perspective as the belief that everything possesses a spirit (a belief which is reflected in some of the earlier observations about sprites and faeries), but rather of inhabiting a position existing in an expanded culture which encompasses everything, in its sticky, withdrawn, uncanny, temporally-phased reality, rather than a ‘Culture’ defined in opposition to ‘Nature’.

The animist is not the one who merely ‘believes’ that the oak tree has a spirit – holding a particular metaphysical view comparable to the metaphysical views of other religions, even if at odds with them – but rather one who lives in a common culture with the oak tree, the cuckoo, the fox and the mountain – but also, in the new animism; the refrigerator, the propelling pencil, neutron stars, holograms and Jack Bruce.20

The world we will be entering is not animism as was, but animism 2.0, because, this time around, humans face all other beings on radically levelled ground, in which all non-human beings (eg., not only animal non-human beings) look back at us as equals, with the result that in this re-animism, “the feeling is rather of the nonhuman out of control, withdrawn from total human access.”21

The world opened to us by global warming is a teeming sea of beings each with infinite awareness within (“Seest thou the little winged fly, smaller than a grain of sand? / It has a heart like thee; a brain open to heaven & hell / Withinside wondrous & expansive; its gates are not clos'd”22), but all still partly sealed off from one another behind event horizons we cannot see behind. Goodbye, totality.

Our challenge is to enter that new animist space. The world we have created may have turned out to be a charnel ground, but it is one we cannot escape from either by playing dead or dreaming of a rebooted pre-modern arcadia. It is a charnel ground, but it is a charnel ground in which “it is the calling of the shaman to enter… and to try to stay there, to pitch a tent there and live there, for as long as possible."23 Perhaps we will meet on the other side.

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013, p71.

Reza Negarestani, ‘Bacterial Archaeology’, Cyclonopedia, Melbourne: re.press, 2008, p49.

Quoted in Victoria Bisset, 'The U.N. warns ‘an era of global boiling’ has started. What does that mean?', Washington Post, washingtonpost.com, 2023-07-29, accessed 2023-08-03.

William Burroughs

Bill Hare, climate scientist and CEO of Climate Analytics, quoted in ‘No one wants to be right about this’, The Guardian, theguardian.com, 2023-07-24, accessed 2023-07-25.

Harlan Ullman, James Wade, Shock and Awe: Achieving Rapid Dominance, National Defense University, 1996, pxxiv.

Morton, Ibid, p2.

Geroge Monbiot, 'The Unseen World’, The Guardian, Dec 2017, monbiot.com, reprinted in This Can't Be Happening, London: Penguin Books, 2021, pp9-10.

Morton, Ibid, p138.

Morton, Ibid, p128.

Amanda Gefter, ‘What plants are saying about us’, Nautilus, nautil.us, 2023-03-07, accessed 2023-09-03.

Morton, Ibid, p154.

Morton, Ibid, p196.

Julien d’Huy, Cosmogonies: La Préhistoire des mythes, Paris: La Decouverte, 2020.

Carissa Wong, '15 unexpected effects of climate change', Live Science, livescience.com, 2023-08-05, accessed 2023-08-06.

William Blake, A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures, pp42-3, in David Erdman, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), Anchor Books / Random House, 1988, E543.

Greil Marcus, The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes, Picador, 2011.

Thomas Cleary (tr), The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra, Book II, ‘Appearance of the Buddha’, Boston and London: Shambhala Publications, 1993, p151.

See Graham Harvey, ‘Introduction’, in Graham Harvey (ed), The Handbook of Contemporary Animism (2013), Abingdon, New York: Routledge, 2014.

Morton, Ibid, p172.

Morton, Ibid, p126.

Great article!

"The animist is not the one who merely ‘believes’ that the oak tree has a spirit – holding a particular metaphysical view comparable to the metaphysical views of other religions, even if at odds with them – but rather one who lives in a common culture with the oak tree, the cuckoo, the fox and the mountain – but also, in the new animism; the refrigerator, the propelling pencil, neuron stars, holograms and Jack Bruce."

I dunno whether you saw this, which was only about 80% tongue-in-cheek: https://peakrill.substack.com/p/elemental-animism

I decided the sentient mycology, or planetary awareness idea comes originally from Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness, when the explorers discover the polyps that can manifest psychic stuff on Antarctica. I think this is Lem's source for Solaris, the novel where astronauts discover a planet with a single organism covering it, that can manifest people from the astronaut's past in order to distract them and break their minds. Who is to say that the Earth isn't like that, with a spiritual mushroom god emanating from a gigantic planetary fungus? Certainly not Terrance McKenna.