Blake… did not claim to be a mystic, and did not use the word. He claimed to be a visionary, an enthusiast, and a Christian, and defined the terms carefully. I have read, and now am reading in newspapers, statements of literary critics and those who call themselves ‘atheistic theologians’ to the effect that Blake had no god but man. People who are not atheists are usually willing to leave to God such important judgments about others. On this subject, as on other statements about himself, Blake seems clear enough. He said always and passionately that he was a Christian, and I know only One who has a better right to an opinion on that subject.

Bo Lindberg1

In his popular book about Blake,2 John Higgs argues that Blake might be a Buddhist, a Daoist, or perhaps a Pagan (he eventually settles on defining him as a ‘Divine Humanist’.) The one thing Higgs is sure about, however, is that Blake is not a Christian.3

Arguing with considerably more interest and plausibility, radical 60s theologian, Thomas Altizer, wrote several books arguing that Blake had both preempted and side-swerved Nietzsche by developing a form of ‘atheist Christianity’.

Blake’s Christianity is a regrettable fact about Blake for those that would palm him off as merely a sort of cheerful, teary-eyed enthusiast for the creative spirit in general.

In this episode of the Traveller in the Evening podcast, Andy Wilson speaks to the psychotherapist and author, Mark Vernon, about why Blake’s Christianity is actually the key to his message and can’t be so easily ignored.

We discuss how, despite Blake’s claims to have no inspiration other than the Bible, commentators cannot resist painting him instead as, at bare minimum, a Gnostic heretic, or, more recently, even as a Buddhist or Pagan.

... we can certainly agree that Blake was a radical Christian in his belief that Churches had perverted Christian truth and that the God of the Christian Churches was really Urizen, Nobodaddy, and even Satan – not the lover of man who empties himself to become identified with Man, but a specter whom man sets up against himself, investing him with the trappings of power which are not 'the things of God' but really 'the things that are Caesar's.' There is indeed much in Blake that anticipates – with far more powerful poetic effect and human authenticity – the ideas of religious alienation in Feuerbach, Marx, and Freud.

Thomas Merton4

It is argued that Blake’s Christianity is vital for recalbrating our relationship to a ‘Nature’ we have previously defined as just more inert grist to our consumerist mill.

Content Warning: Despite the theme of the meeting and the weak joke about Blake being called a Hindu in the title of the meeting, the aim throughout was to emphasise the essential Christianity of Blake’s views; we don’t believe that that involves belittling other religions. Certainly – as Mark reminds us in the podcast – from a Blakean point of view there is only one God, who may be approached in many ways, hence different traditions.

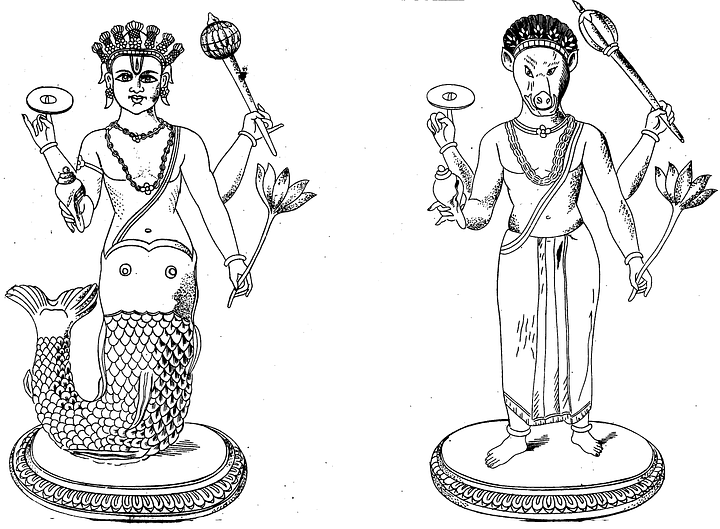

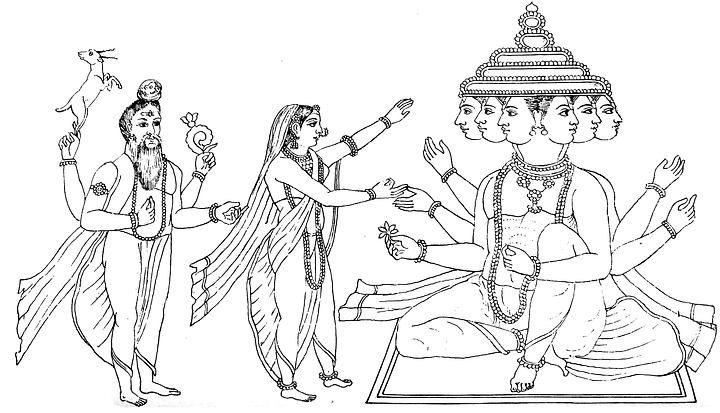

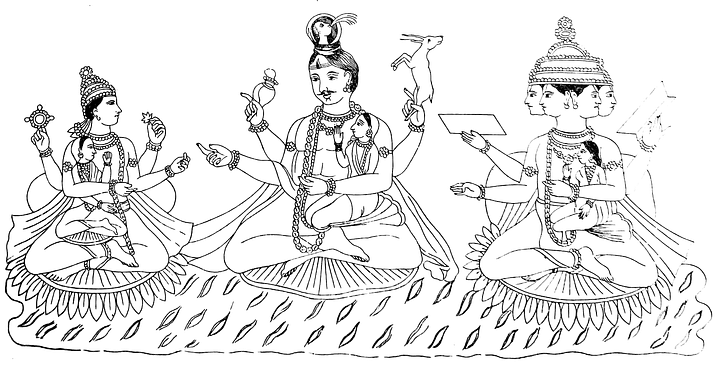

Mention was made during the conversation of Edward Moor’s The Hindu Pantheon, first published in 1810. Moor argued against the contemporary view of Hinduism as backward and paganistic. His book was certainly read by Blake: not only was it published by Blake’s own friend and publisher, Joseph Johnson, but Blake repurposed Moor’s image of Kali to represent Lucifer himself when illustrating Dante (see below).

Lucifer, from Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy (1824-27) c/o The Blake Archive

Mark’s books on Owen Barfield (A Secret History of Christianity), on Dante (Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Guide For the Spiritual Journey), and on ‘spiritual intelligence’ (Spiritual Intelligence in Seven Steps), with their emphasis on Christian belief as an aspect of the evolution of human consciousness, as argued by the Inkling, Barfield. You should check out Mark’s website.

Here’s one of many episodes of the ongoing dialogue between Mark and Rupert Sheldrake.

In Related News

Imagination as the Body of Christ

When Blake says that imagination is the body of Christ, he means it. For years I tried to work out what he meant until it dawned on me that he wasn't speaking loosely or metaphorically. How can imagination be the body of Christ?

Blake Society Talk: Timothy Morton: The Marriage of Religion and the Biosphere

Podcast: On 17th April 2024, Andy Wilson interviewed Timothy Morton for The Blake Society and the Traveller in the Evening about their new book, Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology.

Retipped Arrows of Desire: Timothy Morton's Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology (Review)

In their new book, Timothy Morton enlists Blake to help evolve a Christian ecology where the biosphere is the body of Christ, Hell is the physical world, and religion is the phenomenology of biology.

Bo Lindberg, William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job, Ph.D. thesis, Acta Academiae Aboensi, Turku: Åbo Academi, 1973, p75.

Blake in Beulah: John Higgs's 'William Blake vs the World' (Review)

Clearly, Blake has achieved some sort of broad acceptance. For those such as myself, who believe he has something vital and urgent to contribute, this is heartening. But a closer look reveals a more complicated picture: while Blake has certainly achieved acceptance, it is not at all clear quite what it is about him that has been accepted.

“Blake himself… would simply insist that he was a Christian. Yet it is unlikely that modern Christians would be as sure about this as he was, given his dismissive attitudes to organised religion, his renaming of the Church’s God as ‘Nobodaddy’, and his belief that the God of the Old Testament was a controlling, deluded aspect of our own minds. The idea that the original religion of the British Isles was Christian, long before Jesus Christ was born, is far from Christian doctrine, as is his idea that Jesus Christ was man transformed by imagination… To be a Christian, as Blake understood it, was to be an artist… This is clearly not Christianity as most modern adherents would recognise it. Blake was not a churchgoer, and by the time you get to his opinions on the roles of priests and ‘priestcraft’, it becomes very hard to agree with Blake’s opinion of himself as a Christian.” John Higgs, William Blake vs the World, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p268.

What strikes me immediately about this argument is that every single assertion it makes along the way to its cheerful conclusion is completely wrong, often obviously so. For example, surely many modern Christians could live with the idea that the Old Testament God is merely “a deluded aspect our own minds”; far more than in Blake’s day, I’d guess, which would make him more of a Christian now than then, not less. And it is a permanent feature of post-Reformation English culture that its ‘Christians’ hereabouts be wary of ‘priestcraft’. We burn effigies of Guy Falkes every year to remind ourselves of this. It is part of our national religion. Has Higgs not heard of these developments?

Thomas Merton, ‘Blake and the New Theology' (Apr 1968), The Literary Essays of Thomas Merton, p5.

Share this post