Mike Westbrook, Phil Minton & The Lo-Fi Improvised Music Ensemble with Sue Lynch: Intimations of a Future for Blake’s Music

In November 2022, The Mike Westbrook Band and The Lo-Fi Improvised Music Ensemble performed settings of Blake’s texts that raise questions about how Blake has previously been made to sing.

William Blake Celebration with Lo-fi Improvised Music Ensemble + Sue Lynch solo: 21 Nov 2022, Old Paradise Yard, Lambeth, London

William and Catherine Blake lived in Hercules Road, a stone’s throw from Iklectik, between 1791 and 1800. To mark Blake’s birthday month, the Lo-fi Ensemble will present an evening of music and visuals responding to Blake’s life and work conceived by Freland Green

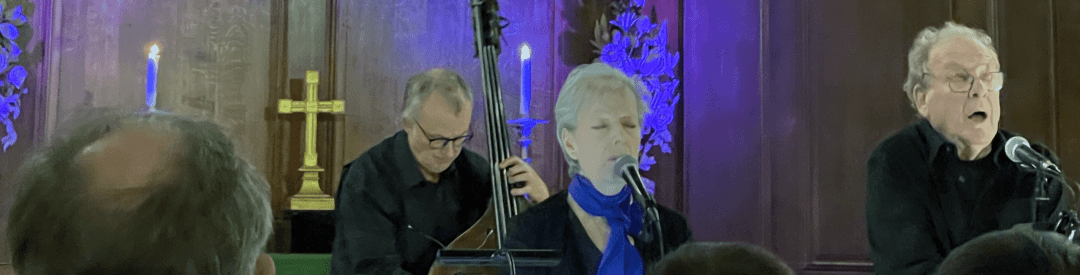

The Westbrook Blake: 24 Nov 2022, St James’s Church, Piccadilly, London

In collaboration with The Blake Society, St James’s, Piccadilly present jazz pianist and composer Mike Westbrook and band, performing his celebrated musical settings of Blake’s verse. Mike Westbrook is joined by Kate Westbrook, Phil Minton and ensemble to perform The Westbrook Blake, with special guest Matthew Bourne on piano.

Make it Strange: Blake’s Musical Uprising

Thou seest the gorgeous clothed Flies that dance & sport in summer

Upon the sunny brooks & meadows: every one the dance

Knows in its intricate mazes of delight artful to weave

Each one to sound his instruments of music in the dance,

To touch each other & recede; to cross & change & return

These are the Children of Los;

Blake, MiltonBlake was a radical in his artistic technique as much as in his politics. He famously “set his forehead” against society,1 but found the artistic tools available to him insufficient to his work, so he had to invent his own. I’m speaking of the structure of his illuminated works and prophecies, whose formal devices were enabled by Blake’s technical innovations. These innovations allowed him freely to mix text and image on a single printing plate in any combination and order he chose, and such freedom gave him a control over the arrangement of text and image unavailable to any other artist of the time. Having mastered the artistic forces of production with his technical innovations (his method of ‘illuminated printing’), Blake was free to sing his own song his own way, unbeholden to publishers, editors, copywriters or other experts. He was free to act originally in his art. But how did he use this freedom, and what does it mean for our understanding of Blake?

Blake as proto-Modernist

Analysis of Blake’s work proves his status as a great proto-modernist, using montage and Brechtian alienation effects to create a decentered art (polyvocal and polysemic) which works for the reader like a mandala, provoking visions when meditated on, rather than a thread that must be followed to a preordained conclusion. Blake perhaps absorbed his critical attitude toward textual authority indirectly from the Moravian church, of which his parents had been members.2 For the Moravians, the written word seemed to create conflict, which is why they concentrated instead on experiencing Christ’s passion, believing that the bond of such deeply shared feeling might unite a congregation, while scripture was more likely to divide it. It’s also why the Moravians often encouraged the study of a range of divergent opinions in order to arrive at a personal interpretation: their emphasis was on promoting insight rather than imposing doctrine. Whatever the inspiration, Blake’s most important texts are impossible to interpret unilaterally, as allegories bearing only a single interpretation. Blake ties monological reason in knots in favour of the cross-talk of competing perspectives related to aspects of his Four Zoas.

This attention to the radicalism of Blake’s formal means has largely been the work of a younger generation of scholars, often applying the insights of post-structuralism, so I will summarise by quoting some of them. Saree Makdisi describes some of the means by which Blake’s polysemia (“capable of having several possible meanings”) is generated;

[Blake’s] movement away from the words on the surface of the printed page is what helps generate and sustain our reading as we shift our engagement with Blake’s text, and even as we alter our understanding of what the text is, from a set of (themselves already indeterminate) words on the page to a set of unstable, ever-varying relations among and between different elements including sound and the visual field on the one hand, and, on the other hand, other plates within the same book or indeed other books altogether. Every time we encounter the text, in other words, we are encountering something that is both the same and different: the same, in that the elements enabling it remain ‘the same’; and different, in that we trace different interpretive paths on every encounter with those elements, which also always change.

This constructive confusion is most obvious in later works such as Milton and Jerusalem (and indeed, in The Four Zoas, despite the absence of Blake’s images) but it is notable that Makdisi applies this understanding of Blake even to Songs of Innocence and Experience, whose poems are sometimes taken to be models of childlike simplicity and directness (in truth they are anything but — the song-structure is a mask employed by the author):

This is one of the reasons that each of the diminutive and seemingly innocuous Songs of Innocence constantly yields, or rather makes available, new readings, interpretations, and meanings. For we are dealing here with a text that sees ‘the same’ as always different, and that regards identity as difference itself.3

For Julia Wright, the polysemia created by Blake’s multi-perspectivism fatally destabilises linear narrative and textual authority:

Blake uses narrative devices to emphasise the destabilisation of the ideological closure of the communal space… He achieves this defamiliarisation, in part, by disrupting the reader’s identification of a character with whom to affiliate his or her point of view or a narrative voice in which we trust… [By], for instance, fracturing dialogues into a series of monologues unheard by other characters, Blake not only represents the mutual alienation of characters within his texts, but also alienates the reader.4 Blake’s multi-perspectivism not only offers an assemblage of perspectives that dissipates the authority of any single view, but also calls attention to the ruptures between those perspectives. The inescapable incommensurabilities submerged in the prefix ‘multi’ characterises the space in which the percipient cannot rest, even for a moment, in another’s perspective: the interstitial domain has neither ideology, nor ruler, nor constitution, and this has implications for the production of shared perspectives in general.5

We have here a view of Blake as someone who challenges political and religious orthodoxies, not merely by disagreeing with them, but by destabilising the system of referents, semantics, readerly discipline and allusions which props them up. This is a Blake fit to stand alongside any modernist in terms of the radicalism and originality of his method: so much so, that the anachronism has thrown generations of Blake scholars off-track.

The failure to come to terms with this aspect of Blake — his fundamental methodological anarchism — means that people assume instead that he had a single, straightforward (if possibly also obscure or arcane) message, coded in his work. Thus they ignore Blake’s warning:

The wisest of the Ancients considerd what is not too Explicit as the fittest for Instruction because it rouzes the faculties to act. I name Moses Solomon Esop Homer Plato… I feel that a Man may be happy in This World. And I know that This World Is a World of Imagination & Vision I see Every thing I paint In This World, but Every body does not see alike. To the Eyes of a Miser a Guinea is more beautiful than the Sun & a bag worn with the use of Money has more beautiful proportions than a Vine filled with Grapes.6

So, when the Jungian reads Blake’s work he discovers a gaggle of Jungian archetypes; the traditionalist finds a world of Platonic forms; the psychologist immediately recognises bilateral brain specialisation. All of them are mistaken.

Blake the Musician

The remixing of Blake’s work into a single essential message, rather than a critique of such messages, is encouraged by the image that has been created of Blake the musician, which derives from comments made by friends about his singing and his musical taste. Blake the musician and listener is held to be committed to the simple and unequivocal. For instance, here is Alexander Gilchrist describing Blake’s visits to the Hampstead home of his young supporter, John Linnell:

Blake… would often stand at the door, gazing in tranquil reverie across the garden toward the gorse-clad hill. He liked sitting in the arbour, at the bottom of the long garden, or walking up and down the same at dusk, while the cows, munching their evening meal, were audible from the farmyard on the other side of the hedge. He was very fond of hearing Mrs Linnell sing Scottish songs, and would sit by the pianoforte, tears falling from his eyes, while he listened to the Border Melody, to which the song is set, commencing-

O Nancy’s hair is yellow as gowd,

And her een as the lift are blueTo simple national melodies Blake was very impressionable, though not so to music of most complicated structure. He himself still sang, in a voice tremulous with age, sometimes old ballads, sometimes his own songs, to melodies of his own.7

This is an especially arresting account, given Wright’s argument that Blake’s complexities are aimed at undoing nationalist discourse, whereas Blake’s later attempts at proposing a positive view run the risk of obscuring his critical impulses, allowing him to be read nationalistically, as someone simply creating an updated national narrative:

With Jerusalem, Blake attempts to vaccinate the body politic against the diseases of ‘error.’ But, through the formulation of this vaccine, his own discourse, by the very logic of vaccination, is brought uncomfortably close to that which it is supposed to eradicate. This is the danger. In his early works, Blake limits himself to the nihilistic subversion of prevailing paradigms or, in other words, to bursting the stony roof. In Milton, however, Blake begins to cobble together his critical stances to form his own vision of the renovated nation, a vision that is completed in Jerusalem. Although he retains subversive strategies, such as multiperspectivism and defamiliarising settings, Blake can only use hegemonic strategies to put his own system into place. Submerging difference in a totalising system and imagining a countercolonisation that sweeps the globe, Blake’s discourse itself becomes hybrid, infected by the very paradigms that he had so long contested.8

Blake is recorded as having composed and sung his own songs in various settings among friends (which Blake scholar has not dreamed of overhearing Blake singing to himself in his workshop?) The image which emerges is of a simplicity, or economy, of means — at least that is how the music has been recalled. It is worth emphasising at this point, however, that not a single note of Blake’s music survives, and we will never actually know how Blake rendered his own words in song.

The complexity of Blake’s engravings is a fact, while the simplicity of his songs is hearsay. We do not know how Blake might have incorporated complexity in his songs. It is not hard to imagine him playing off the mood of the music against the drift of the lyrics, by analogy with the way he counterposes image and text throughout his work, having the image comment wryly on the text, append to it or contradict it, rather than simply echoing and amplify it. But however Blake himself might have sung his own songs, there have since been many others prepared to step into the breech by setting him to music, with a “flood” of interpretations since 1900, according to Keri Davies, such that “Today, Blake is probably approaching Burns as the most set English-language poet after Shakespeare.”9 There is nothing inherently simplistic about English song or folk music, yet it is often understood simplistically, and interpretations of Blake in that vein tend to knock the edges off his vision. The point is that, when thinking about musical settings of Blake, we should bear in mind that the essence of Blake’s art involves a certain opacity and even misdirection, and an absence of didacticism, achieved through complexity and the artful collision of materials.

Mike Westbrook’s Blake

24 Nov 2022, St James’s Church, Piccadilly, London

Phil Minton

voice

Kate Westbrook

voice

Chris Briscoe

saxophones

Karen Street

accordion

Billy Thompson

violin

Steve Berry

double bass

Mike Westbrook

piano

Matthew Bourne

piano

London Song

Let the Slave / The Price of Experience

Lullaby

Holy Thursday*

Long John Brown and Little Mary Bell

The Children of Blake**

The Tyger and The Lamb

The Human Abstract*

The Fields

Golden Builders

I See Thy Form

Words by William Blake

Composed & arranged by Mike Westbrook

Texts arranged by Adrian Mitchell

* Text by Kate Westbrook

** From Tyger by Adrian Mitchell

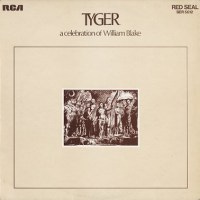

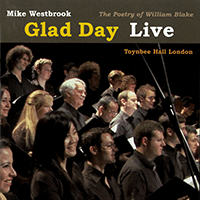

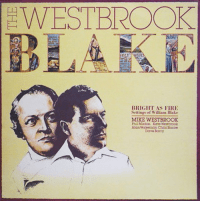

Mike Westbrook has long been a powerful voice in British jazz and, specifically, a long-time interpreter of Blake. His work on Blake goes back at least as far as his 1971 collaboration with Adrian Mitchell on the play, Tyger. These settings of Blake’s texts for Mitchell formed the basis for a number of subsequent performances and recordings, both live and in the studio, with an overlapping set of Blake’s texts in The Westbrook Blake (Bright as Fire) (1980) and then, almost two decades later, Glad Day (Settings of William Blake) (1997). In 2014, a live performance of the Glad Day material was recorded by the same band as tonight’s, and released on both CD and DVD. By the time of tonight’s concert, Westbrook’s engagement with Blake had stretched over half a century.

The band was on Blake’s turf tonight, performing at St James’s Church, Piccadilly, where he was christened in 1757, as part of a season of works promoted by The Blake Society. The repertoire was selected largely from the Glad Day settings, with the addition of Mitchell’s text, ‘The Children of Blake’, from Tyger. A significant difference was the absence of the choirs that were prominent in earlier recordings. Instead, the sole voices were those of Kate Westbrook and Phil Minton, who have sung on all of Westbrook’s Blake recordings as far back as The Westbrook Blake, over 40 years ago. This, then, was a powerfully focused take on existing compositions, with the band consisting of the same musicians who played on Glad Day Live a decade ago, with the addition of Matthew Bourne on piano. This is a band deeply imbued with the music.

Westbrook’s credentials as an interpreter of Blake are impeccable. His early interest in traditional jazz led him eventually to become a face on the British jazz scene at the time of its greatest triumphs, in the late-60s and early-70s, when it intersected with contemporary classical music, European free improvisation, the ‘Rock in Opposition’ of Henry Cow, and Westbrook’s own Solid Gold Cadillac, along with radical theatre and politics, all of which Westbrook engaged with, adding to the mix his own awareness of English song. This period created the cadre of British avant-jazz for the next half a century: Derek Bailey and Tony Oxley, Elton Dean, Keith Tippett, Ian Carr and similar luminaries. From Joe Harriot on there had been an attempt on these shores to break with American styles and, increasingly, develop authentic local alternatives. Westbrook himself claimed to be part of a movement in jazz “to question the American orthodoxy and to work on developing an independent voice.”10 For Westbrook, developing an authentic local voice wouldn’t mean jumping on board with the then modish nationalism of ‘Swinging Britain’. Instead, Blake turned out to be a perfect foil for exploring such roots from a radical perspective, since his Englishness resists any easy identification with England, as Blake was always fundamentally at odds with such positivism.

In tonight’s performance, Westbrook and the band moved easily between unembroidered song and passages of intense colour and musicality, and much in between. Billy Thompson (violin) and Karen Street (accordion) were notable in bringing extraordinary power and articulation to the music, though with such an experienced group there were highlights everywhere. Blake’s lyrics are, of course, themselves deeply engaged and embattled: in London Song: “… the Chimney-sweepers cry / Every blackning Church appalls / And the hapless Soldiers sigh / Runs in blood down Palace walls”11 With a band like this there was much to enjoy: Steve Berry’s double bass playing flowing like lava alongside the querrulous intelligence of Westbrook’s piano and Biscoe’s saxophone in Holy Thursday (perhaps the most successful of the songs aired tonight); Matthew Bourne’s expressionist drama in The Human Abstract; Billy Thompson’s gale of violin during The Price of Experience. It would be unfair to pick anyone out for special mention, the standard of playerly wit being so high, and what with everyone being so at home with the material.

There was plenty of evidence of contrasts and back-and-forth interplay between Minton and (Kate) Westbrook’s vocals, with Westbrook delivering often strident and declamatory performances (on Lullaby and London Song, for example), while Minton — a master of free vocalisation — providing everything from song to jazz scatting and beyond, at times unravelling entirely into glossalalia.

In a perfect world, the Westbrook / Blake repertoire might be developed further by incorporating an even wider sonic palette from the further shores of free improvisation and modern composition (spectralism, anyone?). Perhaps the studio could add more by way of dub and mixological magic (as it does in Mark Stewart and the Maffia’s peerless version of Jerusalem). But until those things happen, these performances by the Westbrook Band pass as a summary of what the best of British music has created in the course of a long and committed engagement with Blake. The fury and tenderness of Blake’s texts were present, but without the songs turning into tidy homilies: ideas clash, collide, contrast with, and comment upon one another; they engage the listener, drawing them into the fabric of the music, without hectoring or closing off interpretation.

William Blake Celebration w/ Lo-Fi Improvised Music Ensemble + Sue Lynch

Monday 21 Nov 2022, Iklectik, Old Paradise Yard, Lambeth, London

Another performance accompanying Blake texts, this time by the Lo-Fi Improv Music Ensemble, took place just a few days earlier, also in the Blakean heartlands — in this case, at Iklectik, in Lambeth, near where Blake’s home in the Hercules Buildings had stood when he was creating his most radical work, and next door to the council-funded mosaics of Blake’s images that line the railway arches snaking out of Waterloo.

As for the Lo-Fi Ensemble, arguably they are coming at Blake from the opposite ends of the spectrum experientially compared to Mike Westbrook, being amateur improvisers taking part in workshops at Longfield Hall, led by Stuart Wilding. Arguably, their inexperience showed, with members sometimes leaning on familiar habits, but the rough and ready nature of the improvisation suited the context perfectly, adding something like a demotic touch to the proceedings that Blake might well have liked.

The music was much abetted by the presence of guest saxophonist, Sue Lynch, who runs The Horse Improvised Music Club with Adam Bohman. Lynch played improvisations that married subtle echoes of the funk of Armstrong and early New Orleans jazz, along with her own, often wild abstractions. Sometimes she sounded as if she were moulding raw spit and air with her lips and lungs, like Bill Dixon, perhaps. In any case. she added gravity to the mix, sounding simultaneously lyrical, thoughtful and alive to the immediate context.

Also in attendance were the dancers Kalina Petrova and Aleksandar Isailovic of the London Butoh Dance Company, playing out a loping dialectic of intertwined moves, coupling and decoupling as they scuttled about the stage, sometimes embracing, sometimes seeming to repel one another, but mostly locked into a dialogue of move and countermove, action and reaction.

The texts, selected and read by Freland Green, who organised the entire performance, were original, and far from obvious choices — not the usual (seeming) transparency of Songs of Innocence and Experience, but the full-blown terror, obliquity and confusion of The Four Zoas, complemented by excerpts from the journal of John Stedman, the soldier whose Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam was published by Joseph Johnson in 1796 with engravings by Blake, and which was a cause celebre among abolitionists. The texts from Blake painted a picture of the toil and troubles of working people; “look upon our sore afflictions among these flames, incessant labouring. Our hard masters laugh at all our sorrow,” concluding that “Jerusalem came down in a dire ruin over all the Earth, She fell cold from Lambeth’s Vales in groans of dewy death,”12 while Stedman’s journal entries paint a fleeting but pungent picture of Blake’s London, and are worth quoting at length:

Jun 1795: Visit Mr. & Mrs Blake. News at Paris, a member of the Convention shot, forty guillotined. Dutch declare war to England. London: disloyal, superstitious, villainous, infamous. An earthquake prophesied by Brothers. May leave town. At Salisbury, a dozen Irishmen flogged. At Brighton, rebels sentenced. Gave a blue sugar cruise to Mrs Blake. Dined with Palmer, Blake, Johnson, Rigaud, and Bartolozzi. 160 emigrant dragoons deserted. Copenhagen burnt. Two men shot at Brighton, two hanged for mutiny. A riot at Birmingham. How dreadful, London. A Mr B declared openly his lust for infants, his thirst for regicide, and believes in no God whatsoever. I saw two Catawba Indians at Sadlers Wells. Gave an oil portrait to Mr.Blake. Dined at Blake’s. Riots in St George’s Fields.

Aug 1795: The inn is full of whores and rascals. The dragoons, all home from continent. A hot quarrel with Johnson. I visit Mr.Blake for three days. I leave him all my papers. Three murderers hung at Kennington Common. I visited the King’s Bench. A poor cow hamstrung by the infernal butchers.

Sep 1795: 300 whores in the Strand. French prisoners come home. Abershaw &c hanged. Saw a mermaid. Russian fleet, down. Meat and bread abused. Two days at Blake’s. Quiberon expedition failed. 188 emigrants executed. Covent Garden burnt. The King’s coach insulted. The bill passes against Seditious meetings. London – everything made up. All knaves, fools, cruel to excess. Mr Blake was mobbed and robbed.13

Tying everything together tonight were the images projected across the entire stage area, which connected the texts, sounds and movement all to Blake and Lambeth through the use of pictures of the nearby Blake mosaics alongside scenes of local people and protests over the last century. With so much happening, Blake and Stedman’s texts sounded like trumpet blasts clearing a path through the action on stage. This was an original take on Blake, carefully crafted to meet its subject matter and location.

A Better Blake in Song

As little as regressive listening is a symptom of progress in consciousness of freedom, it could suddenly turn around if art, in unity with the society, should ever leave the road of the always-identical.

Theodor Adorno14

In the performances reviewed here we were treated to converging musical approaches to Blake’s legacy. Both emphasised “the improvisatory displacement of things”, as Adorno put it;15 both avoided the increasingly common use of Blake as a token of middle-class progressive nationalism and a pining for social peace and constructive good works. Their approaches favoured instead an urban, electric engagement with the texts, steeped in jazz and the avant-garde. While Blake is increasingly misrepresented as a rather placid social democratic figure — as opposed to the unclubbable anarchist Ranter he surely was — here we saw glimpses of a hipper Blake, still way ahead, but ready and able to mix it up with progressive, searching art.

It is remarkable that, while in the visual arts, Blake is associated with political and artistic radicalism such as that of the Surrealists and Situationists, in music he has long been associated with mainstream, soluble fare such as The Doors and Billy Bragg. With Westbrook and the Lo-Fi Orchestra, on the other hand, we have proof that even if you line up all the pop stars in the world to salute Blake’s flag, you still can’t stop his radicalism bleeding through the social-commercial fabric, offering a righteous and weighty alternative to the popsicle academy’s fluffy, low-carb pleasures for as long as there are people willing to listen. Let’s hope to hear more of this in the years to come, as we need to hear Blake more than ever.

The post Mike Westbrook, Phil Minton & The Lo-Fi Improvised Music Ensemble with Sue Lynch: Intimations of a Future for Blake’s Music first appeared on The Traveller in the Evening.