Ithell Colquhoun: Mantic Stains, Sex & Surrealism

The otherwise splendid Ithell Colquhoun show at the Tate St Ives underplays the affinity between the occult and Surrealist sides to Colquhoun's weapons-grade psychic automatism

An old woman motionless on a short straight puff of smoke

pointing to the rain of ants on the sea

Next to the cold rock there is an eyelash

A piece of torn flesh forecasting bad weather

There are six lost breasts in a square of water

A rotting donkey buzzing with little miniatures

representing the beginning of springSalvador Dalí, To Lydia of Cadaqués (1927)

We are lucky to be around to witness an upturn in the fates of some cruelly neglected women connected with Surrealism. Historically, it is only recently that Leonora Carrington, Unica Zurn, Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, and Claude Cahun (to name just a few) have swung more clearly into view, thanks in part to the efforts of researchers and writers committed to setting the record straight.

Among British surrealists – other than Carrington, who is by now perhaps even rather popular – there are figures such as Eileen Agar, Emmy Bridgewater, and Grace Pailthorpe, all deserving further study and wider appreciation. Edith Rimmington (1902–1986) certainly has yet to find the recognition she deserves.

This gendered myopia (or you may say: ‘hateful misogynist prejudice’) is compounded by the way Britain itself has been perceived as a tame Surrealist backwater: we can’t all be as totally wired as André Breton, Hannah Höch, and Benjamin Péret. Being a woman just makes things worse.

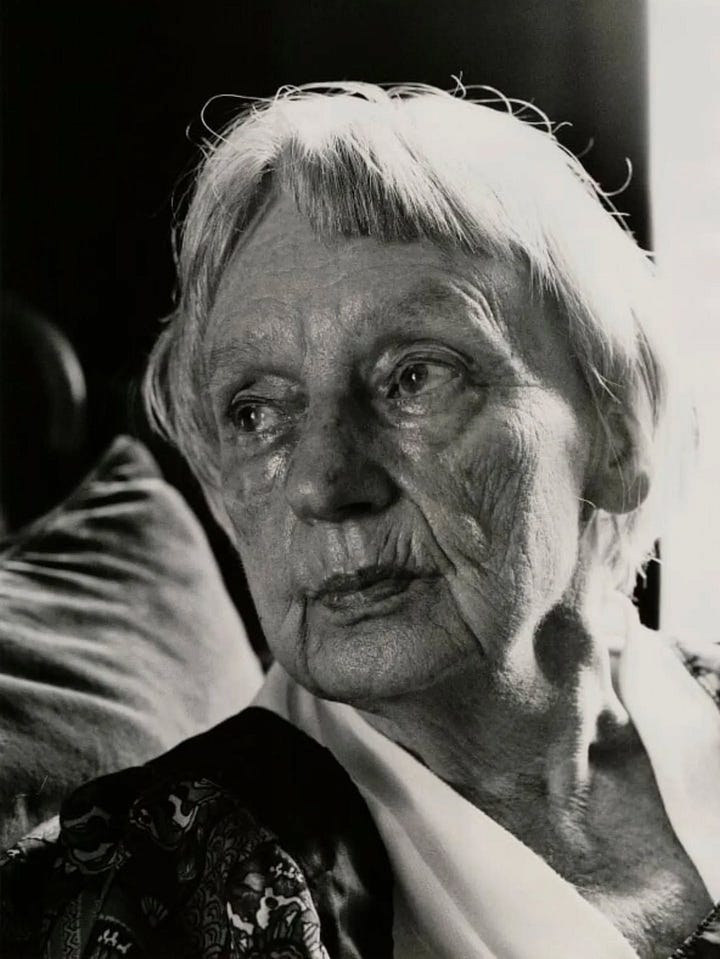

Despite this, Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) has been the focus of escalating scholarly and countercultural interest for a while now. Having died in obscurity in the Cornish village of Lamorna in 1988, nearly forty years ago, Colquhoun is now not only recognised by many as a Surrealist artist of note, but also, increasingly, as a pioneer in a series of esoteric, magical, theosophical and new-age practices, all of which greatly influenced her art, while the art itself was increasingly given over to these esoteric practices, so that she is also now seen as a crucial figure in the emergence of a generic ‘occult art’.1

The pace of this resurgence stepped up with the merger of the two main Colquhoun archives a few years ago, leading to more research and further insights, inspiring the current exhibition of Colquhoun’s art alongside newly surfaced artefacts and documents, at The Tate in St Ives, running until May 2025. The idea is to show Colquhoun in an updated perspective, given what has been learned.

Slade in Flame: Occult Roots

Myth must Break through the crust, scatter 1000 new comets in the void, illuminate the black sky with Bengal lights, decorate the day sky with vapors fumes what superhuman shape shapes may not burst from the next eruption, or tender beings, who evolve themselves in the light of gold!

Ithell Colquhoun, The Water-Stone of the Wise2

Some of the briefer biographies in galleries and guidebooks say things along the lines that Colquhoun had ‘an ordinary upbringing’, which proves that all things are relative, since I find it hard even to imagine what it must have been like growing up in the refined atmosphere of a British Civil Service household, posted abroad as a cog in the machine of Empire, as her father was. I doubt it was ‘ordinary’.

Colquhoun was born in Shillong, East Bengal, in 1906, in what was then British India: she later claimed she was lucky to have been born ‘between worlds,’3 as the title of this exhibition has it: between India and England, East and West, the esoteric and the quotidian, the weird and the straight – although Colquhoun was, in fact, beyond all shadow of a doubt, extremely weird and in no way ‘straight’.

As a teenager she had been repatriated with her family to Cheltenham – the home of so many returning memsahibs that it became known as ‘the Calcutta of England’. She attended Cheltenham Ladies College and (the ‘progressive’: it let women do life drawing classes) Cheltenham Art College (1925-1926) before setting off for London to attend Slade School of Fine Art in 1927.

The Slade then was directed by Harry Tonks, who headed up the regime of anatomical studies, life-drawing and ‘copying from nature’ that formed the basis of Colquhoun’s training. She later said that Tonks and the Slade tried to teach her “to draw in the style of Michaelangelo but paint in the style of the… Impressionists.”4

woman and the way of knowledge: Genesis to Holofernes

Woman is close to the Earth. One could imagine the first state was matriarchal… And the big old Snake Nature in the Tree of Knowledge told Eve to give the apple to Adam (she eats too!) The old Snake Nature wanted him to take the way of intellectual development.

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement5

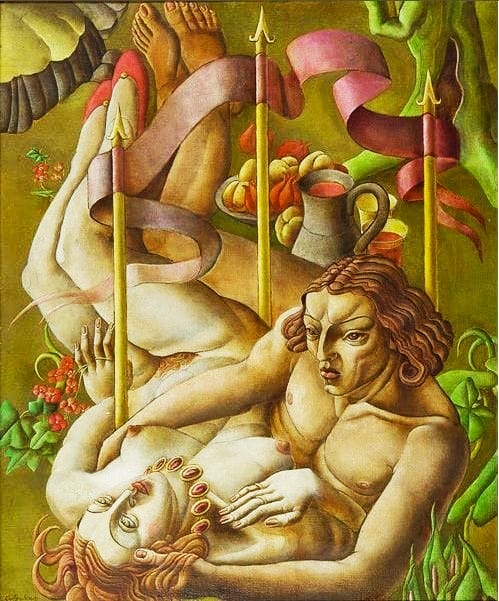

The separation of form and content (colour) implied by that dualism of Michaelangelo and Monet is reflected in Colquhoun’s responses to a course requirement to paint a selection of mythic scenes chosen from a mandated list. The paintings (Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1929; The Judgement of Paris, 1930; Marlowe’s Faust, 1930; and The Death of Lucretia, 1931) combine cubo-futuristic figures and arresting colours in compositions heavy in symbolism – inevitably, given the brief: Colquhoun certainly couldn’t pass up a chance to illustrate Marlowe’s Faust with an image of the snake “who first corrupted man,” wrapped around the tree of knowledge (bottom left).

I don’t know when Colquhoun’s great interest in colour theory first developed, but some version of it is at work here. She must have been familiar with at least the outlines of alchemical colour theory, having written and staged her play The Bird of Hermes / The Goose of Hermogenes back in Cheltenham, a story based on alchemical concepts. The repeated use of contrasting, alternating red and white – albedo and rubedo, alchemical symbols of the second (purification) and fourth (completion / perfection) stages of the alchemical work – create the suspicion that alchemical concepts were already on Colquhoun’s mind here, as they would be in future.

In the apocryphal Book of Judith, the heroine slits the throat of the tyrannical Assyrian General, Holofernes, while he’s drunk. Holofernes oppressed the Jews as a regional commander for King Herod, and Judith commits his murder for the good of the people, justifying herself (at least in the Friedrich Hebbel play that takes her name) by saying: “Even if God had placed sin between me and the deed enjoined on me – who am I to be able to escape it?” Sin is thrust upon her as the cost of doing right.

Judith embodies the paradox of this dialectic that spins good (liberation) out of evil (death and murder) by drawing down evil upon oneself, wrestling the antinomies of reason to the floor along with Holofernes’ corpse. Are we really meant to rationalise such things? Maybe Judy is a Punk.

György Lukács stalked the heights of ethical intransigence in his quietly histrionic Theory of the Novel (1916), wielding quotes from Judith herself and Dostoyevsky’s Prince Mishkin dialectically like a roadman’s razor in defence of his precious ideals… until he reversed gear to become a Commissar in the Hungarian revolutionary government of 1918, commanding troops in battle while also the Commissar for Education.

By then Lukács was depraved enough to describe Judith’s words in accepting the need to sin as “incomparably beautiful,” arguing that it was only those like himself, who properly rejected evil, who could kill in a properly moral fashion.6 For Lukács, Judith offers a way through the door that stops intellectuals from achieving lift-off, practically speaking: she kicks down the door barring the intellectual’s desired ‘egress into action’, the permanent scar of their intellectualism, their original sin.

The tale makes Judith a paragon of female empowerment and, more esoterically (and therefore more likely to be the cause of Colquhoun’s interest), the female divine. That Artemesia Gentileschi painted such an electric rendering of the scene reflects how much the story has impressed itself on women historically, who anyway have more right than most to succumb to its logic – consider that the face of Holofernes here is said to resemble that of Gentileschi’s rapist, Agostino Tassi. To what extent was Colquhoun aware of these resonances? A lot, I’d guess.

Colquhoun actively participated in occult groups, publications and secret societies throughout this period, and uninterruptedly and increasingly so for as long as she could read or write a letter. With a helpful introduction and recommendation from a distant cousin, she even applied for membership of the Golden Dawn itself around this time, and was interviewed as a candidate but refused.

Her art at the time reflected her occult ideas, but confined them within the aesthetic borders of her training. The esoteric symbolism, colour theory, sacred geometry, traditional icons, and so on, rattle the frame without ruffling any feathers. Dorothy remains parked, artistically speaking, down a tastefully illuminated dead end in Kansas. Colquhoun’s vital forces only really emerge in public when she becomes a Surrealist.

Whatever the limitations of her art at this point, several of these early efforts certainly share something of the force and intensity of later works, such as her enamels, Dust Devil and Volcanic Landscape of 1969. Across forty years of practice and repeated changes of style, media, materials, and thematic and intellectual focus, there is a unity of sensibility to Colquhoun’s work, a sincerity and an insistence, reaching back to the beginning of her art.

queen of communicating vessels

The current exhibition, somewhat slyly, tags Colquhoun and her work as located ‘between worlds’, which worlds I suppose are, in the first instance, those of East and West, the esoteric and the mundane, &c., which, as already noted, Colquhoun herself later said she felt blessed to have been born ‘between’.

More significantly, in terms of the reception of Colquhoun’s art, I think we’re being prompted to imagine her as caught between the worlds of art, art criticism and art history on the one hand, and that of esotericism, theosophy, druidism, witchcraft and sex magic on the other: art or magic? tepid art theory or spicy occult power? Take your pick.

Speaking of her as existing ‘between worlds’ leaves open the perhaps obvious question: is Colquhoun ‘between worlds’ in the sense of being caught between them; too hot for either side, suspected by all; or is she instead ‘between worlds’ in the sense of constituting an exemplary medium and point of intersection between communicating vessels? Colquhoun can appear to be any of these things depending on your understanding of her esotericism and her Surrealism.

To answer the question, we must be clear about the relationship between the ‘art’ aspect and the esoteric ‘content’ (burp!) of Colquhoun’s work. At the heart of her work are two dimensions, attitudinal and methodological, which, taken together, constitute her identity as an artist. How are they connected?

The attitudinal, orienting dimension takes the form of an intuition which is irresistible to Surrealism but not of it. This intuition makes up the admission level of occultism; its faith in the marvellous interconnectedness of things. This orientation appears to have been part of Colquhoun’s stance from an early age. It manifests in her work in characteristic ways.

Often it involves her adopting the hermetic principle, “as above, so below” – the idea that the material world is a mirror of spiritual truth, so that the things of the world symbolise spiritual realities through systems of correspondences. Adopting this point of view opens one up to comprehending material and spiritual truths alike in their inner connection. Call this the perspective of a consistent, cheerful monism.

Another manifestation of the basic occult orientation in Colquhoun is her fascination with the figure of the ‘divine androgyne’, as imagined by Jacob Böhme and William Blake, which supersedes the male and female principles, overcoming all contradictions, and is associated with sexual expression and libidinal freedom.7 The androgyne has a pivotal role in alchemy as the product of the ‘chemical wedding’ of opposed principles, the overcoming of the opposition of spirit and matter.

transpersonal, expanded animism

Panic is the sudden realization that everything around you is alive.

William S. Burroughs, Ghost of Chance

The final expression of the occult intuition in Colquhoun – the key to her contribution to Surrealism, in fact, and her significance as a Surrealist – is her ‘expanded animism’. Animism is generally, incorrectly thought of as consisting of a belief that there are spirits ‘out there’ in the world that can be communed with; a wider community, a whole new team of furry and feathered, creeping and crawling neighbours.

She did not claim necessarily to own all of these feelings and attitudes

Colquhoun’s animism is better understood as the view that results from an attenuation of the boundaries between her self and other things achieved through her magical studies and practices. This slackening allows other forces / minds / principles to speak through the medium of the self (absent the rational mind, which is suppressed by opening it to the promptings of the ‘mantic stains’ – marks created at random.)

That which speaks in such a situation could be one’s own unconscious finding expression, or it could be your unconscious channelling the intelligence of an other. On realising this, the invisible empire of the mind, with its Great Chain of Being, totters.

Colquhoun experienced personal and occult powers alike – will, intention, attraction and repulsion, fear, pleasure, and the anticipation of pleasure – pass through her. She did not claim to own all of these feelings and attitudes: that is what makes her an occultist and (‘expanded’) animist.

Often she might be channelling them – from plants and animals, from the dead, from colours, from the Earth, from standing stones, from spirits, depending on the work she was doing. Her self and the powers that moved in her co-mingled in her art and her magical practice. Being open to the unconscious is being open to the other: borders blur and conventions strain.

The occult persuasion had been with Colquhoun from the start. What completed it and made her the artist she became was her discovery of Surrealism, automatism and the techniques developed by the Surrealists to map the unconscious. Colquhoun’s art from now on used such techniques to open (via her body and the unconscious) lines of communication with the energies and personas she sought contact with in her magical practice.

Mantic Stains #1: Colquhoun and Surrealism

Let art resolutely yield the passing lane to the supposedly ‘irrational’ feminine, let it firstly make enemies of all that which, having the affront to present its self-assurance solid, bears in reality the mark of that masculine intransigence which, in the field of human relations at the international level, shows well enough today what it is capable of.… Those of us in the arts must pronounce ourselves unequivocally against man and for women.

André Breton, Arcanum 17 (1944)8

Swedenborgian principles can be discovered in Surrealism, which aimed to join ‘two distant realities’ on the same plane.

Nadia Choucha9

Colquhoun became acquainted with Surrealism in Paris in 1931, where she read about the group and saw several of Salvador Dalí’s works exhibited. This was when Dalí was developing his ‘paranoid-critical’ approach, creating double (actually, multiple) images, splitting the affective field of the picture surface in two, making systematic ambivalences that shatter the rationality of the real to reveal the marvellous within. In Dalí’s words, paranoid criticism was “a spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectification of delirious associations and interpretations.”10

Paranoia-criticism superimposes two realities to bring out a third

According to the historian of Surrealism, Mark Polizzoti: “among the most striking transformations of critical thinking… is Salvador Dali's theory of paranoia-criticism. Related to the centuries-old tradition of the image-devinette or image d'Epinal, from Arcimboldo's vegetal faces to Wittgenstein's duck-rabbit to the ubiquitous dual image of ‘What's on a man's mind’… paranoia-criticism superimposes two realities to bring out a third.“11

In pursuit of her occult interests, Colquhoun aimed precisely to ‘bring out’ a third (or fourth, fifth, or more) reality in her work, and she drew deep from Dalí in this (and anyway, as Nadia Choucha noted, isn’t Surrealism itself innately occult in its aim to short circuit the dual planes of the real and the unreal?) Several of Colquhoun’s works of the 30s and beyond create the same ‘double take’.

Throughout the decade she grew confident painting in alignment with such Surrealist attitudes, in tandem with her own, which were easily fused with them. To put it another way, Colquhoun found in Surrealism an approach into which her existing occult concerns could fit without remainder, while absorbing from it the ‘technology of the marvellous’ that powered her researches.

In Scylla (1938) – one of her most recognisable images, used to promote the St Ives exhibition – Colquhoun references the myth in the Odyssey of the man-eating monster, Scylla, on one bank of a fast and narrow straight, on the other side of which is the equally lethal monster, the ‘sea swallowing’ Charybdis. Sailors steering hard to avoid Charybdis’s maelstrom ran the risk of ending up dying in the jaws of Scylla instead. It’s how the Greeks used to spell ‘a rock and a hard place’.

Two phallic rocks jut up vertically in a shallow turquoise sea

Two pink-brown phallic rocks jut up vertically from a shallow turquoise sea. At their base is sand and a red-brown coral or seaweed. The gap between the rocks takes the shape of the vesica piscis / mandorla / vulva. We see the prow of a small ship approaching this gap at an angle. A phallus approaching a vulva? But the boat also has the shape of the mandorla.

Colquhoun said the idea for the painting came to her in the bath, which creates a different perception, duck to the rock's’ rabbit? She is the Scylla the boat approaches, possibly to meet its doom: will Odysseus’s crew survive an encounter with Colquhoun in the bathtub that is the ocean?

I don’t know if Colquhoun had seen Dalí’s Metamorphosis of Narcissus from a year earlier (1937), but Scylla puts me in mind of it. Dalí paints Narcissus as a rock pile by the river bank, resting in its shallow water. The watery setting of both paintings, Scylla and Narcissus, suggests decomposition and decay, the dissolution of things, while the rocks suggest petrification and the channelisation and freezing of desire. Narcissus is reifying in front of us as he flips his ground state, adopting the locked-in narcissistic posture in which he can no longer tear his attention from his own image – or rather, he can do so only at the risk of tearing himself apart: the narcissistic dilemma.

Gouffres Amers (1939) forms a pair with Scylla. The title is taken from a line in Baudelaire’s The Albatross (1857) about a ship gliding over ‘the bitter deep’. The man depicted has decomposed almost entirely, with parts of him missing, his resting penis replaced by a leaky pipe sprouting a timid flower. Perhaps he is one of the sailors from the boat, consumed by Scylla, discarded, lost and disintegrating.

The gradual emergence of the

Instincts. the hard sharp

Laughter of the sudden daylight

And out of the sleepy funnel

Breath

Merges again with the waiting

Whiteness of what is to be

David Gascoyne, Recuperation (1936)12

June 1936. After a winter long drawn out into bitterness and petulance, a month of torrid heat, of sudden fluorescence, of clarifying storms. In the same month the international surrealist exhibition broke over London, electrifying the dry intellectual atmosphere, stirring our sluggish minds to wonder, enchantment and division.

Herbert Read, Surrealism13

Colquhoun cemented her relationship with Surrealism at The International Surrealist Exhibition, held over three weeks in June–July 1936 at the New Burlington Galleries, Mayfair, in London. Around seventy artists had work shown, including axial figures such as André Masson, Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst.

There were talks and presentations by André Breton (Limites non-frontières du Surréalisme), Herbert Read (Art and the Unconscious), Paul Éluard (La Poésie surréaliste), Hugh Sykes Davies (Biology and Surrealism) and Dalí, who famously turned up to talk about his paranoid-critical method wearing a deep-sea diving suit, and with two drooling wolfhounds on a leash. When the helmet could not be removed for him to start the talk, Dalí was rescued by one of the organisers, the great poet, David Gascoyne, finding a spanner with which to jemmy off his helmet, saving the delirious young Dalí from drowning in his own poisonous exhalations.14

Colquhoun was in the audience. She says that, while the talk was memorable, it was also almost entirely unintelligible due to Dalí’s high-pitched voice and atrocious French accent, which was actually a Spanish accent speaking bad French. She also claims that, contrary to most reports, it was Gala who managed to twist Dalí’s helmet off in time. She concludes: “Dalí was minute, feverish, with bones brittle as a bird’s, a mop of dark hair and greenish eyes.”15

Colquhoun intuited that Surrealism could help her capture occult realities on canvas. She picked up at first on Dalí, whose methods she leaned on, but it was the Surrealists’ use of automatism that drew Colquhoun inexorably in, cementing a life-long commitment to Surrealist investigation, even when not in lockstep with Surrealist strategy and discipline. From this point on, automatism was the engine that drove her pursuit of the occult in art. As Amy Hale says, “throughout her life most of her output was automatic in nature…” It is at this time that she first dialled in to it.16

Mantic Stains #2: Pure Psychic Automatism

If at the end of a lesson the classroom is disordered and the explorers splashed, so much the better. Does not all inspiration come from the multitudinous abyss?

Ithell Colquhoun17

Automatic writing had been around since at least the time of Walpole and Carlyle, in the eighteenth century, before Breton was using it to treat shell-shocked soldiers in WWI. Freud used it as an analog of free association, to manifest the unconscious, drawing it into the psychoanalytic process. André Breton and Philippe Soupault, building on Freud, used it to write The Magnetic Fields (1920), the first work of literary Surrealism, and the gateway to everything that followed..

In the Surrealist Manifesto (1924) Surrealism itself is famously defined as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express…the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”18 (As Colquhoun noted, “it is obvious from the context that by ‘thought and ‘the real functioning of thought’ Breton means the unconscious.")19 To summarise, repeat and emphasise: Surrealism is psychic automatism.

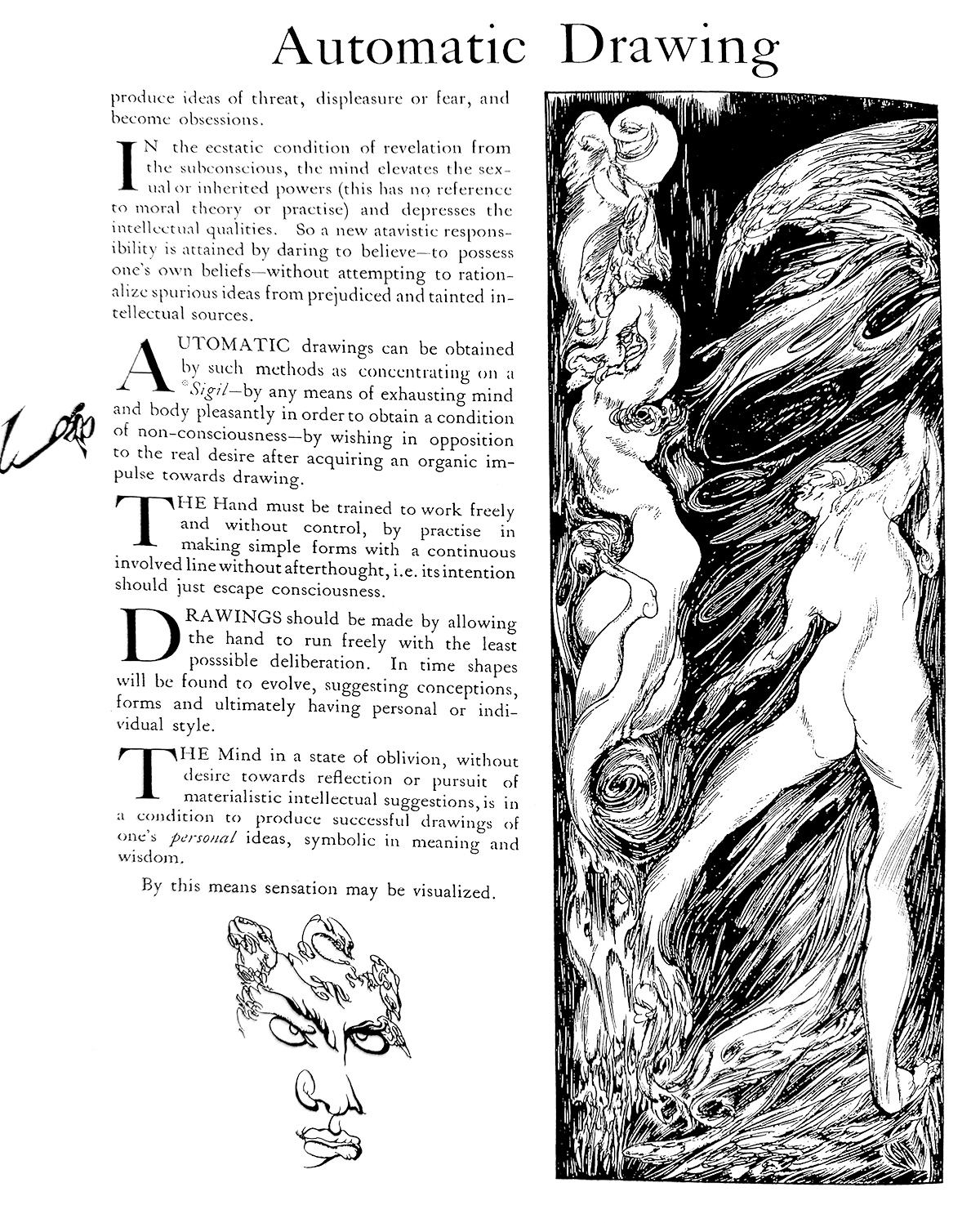

sensation may be visualised

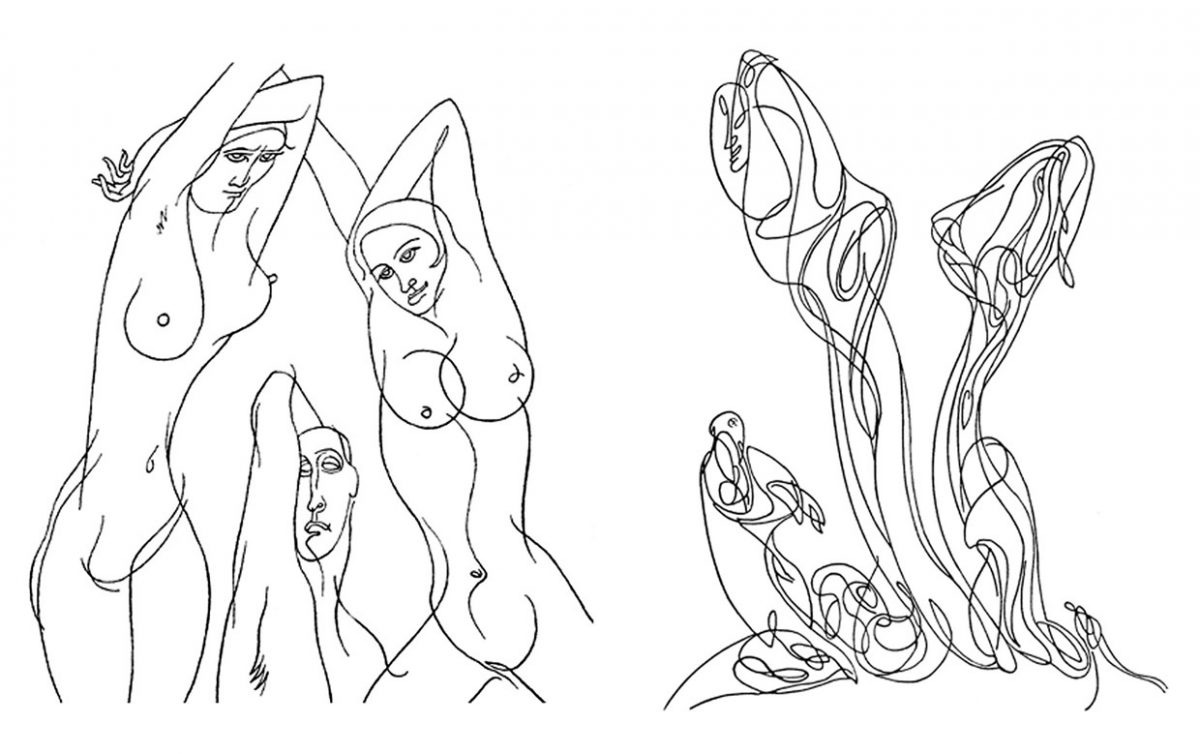

The automatic text was soon rivalled within the Surrealist group by automatic drawing, as practiced by Hans Arp, André Masson, Dalí, Joan Miró, and more.

Before Surrealism, automatic drawing had already been an occult occupation, not only among spiritualists and table-tappers, but in the hands of the seminal British occultist, Austin Osman Spare, who wrote of it in The Book of Pleasure (1913) and used it widely in his art: “In the ecstatic condition of revelation from the subconscious, the Mind elevates the sexual or inherited powers… and depresses the intellectual qualities… The hand must be trained to work freely and without control… ie., its intention should just escape consciousness. The Mind in a state of oblivion, without desire towards reflection or pursuit of materialistic intellectual suggestions, is in a condition to produce successful drawings of one's personal ideas, symbolic in meaning and wisdom. By this means sensation may be visualized.”20

Here, automatism clears the path for one to access and formulate these ‘personal ideas’. I assume he thought it could be used to open a dialogue with his own atavistic sub-personalities and other occupants – whether personal, ideational, affective, autonomic or symbolic – of his expanded mind.

The first ‘techniques’ of automatism were just disciplines and exercises through which the artist sought to loosen the rational control of their mind, the tyranny it exercises over the products of the conscious mind, letting things emerge instead according only to perfectly spontaneous promptings from within.

In this state, the rational mind was still there, but spinning its wheels, kept numbed or distracted to allow the other to speak in its place. Means were soon adopted for encouraging this state of spontaneous production: days and nights were spent obsessively free associating or drawing while hypnotised, or while meditating, conversing while half asleep, writing while drunk or hallucinating, and so on.

accidents, stains, found objects

objective chance

Other methods worked not so much by attenuating rational control, but by prodding the body or the irrational mind into action in its place; providing irrational promptings to the non-reasoning mind.

Ithell Colquhoun would be one of the great proponents of Surrealist automatism in Britain for years to come.

Chance events, accidents (‘stains’), found art and found objects (object trouvé) (“It is hardly necessary to point out that the same unconscious process which makes a mantic stain and recognizes its pictorial scope also selects and illumines that morsel of external reality which constitutes ‘found object’.")21 all created such precipitations, taming the rational mind by prodding the imagination behind it, much as the imagination is coaxed from sleep when you watch the clouds go by, or gaze at the coals burning in the grate.

As the powerhouse of Surrealism, automatism was extended by its partisans into all suitable media toward which it might extend, with the creation of further techniques for exploiting randomness, aleatory processes, luck, spontaneity, ‘objective hazards, improvisation and chaos to unlock the marvellous.

You might suppose that the practice of seeking visions by staring at the inscape of things might lead you to occasionally see more deeply into the actually-existing surreal, away from any thoughts of the canvas. Whatever the case with that, Colquhoun became a great proponent of Surrealist automatism in Britain for years to come.

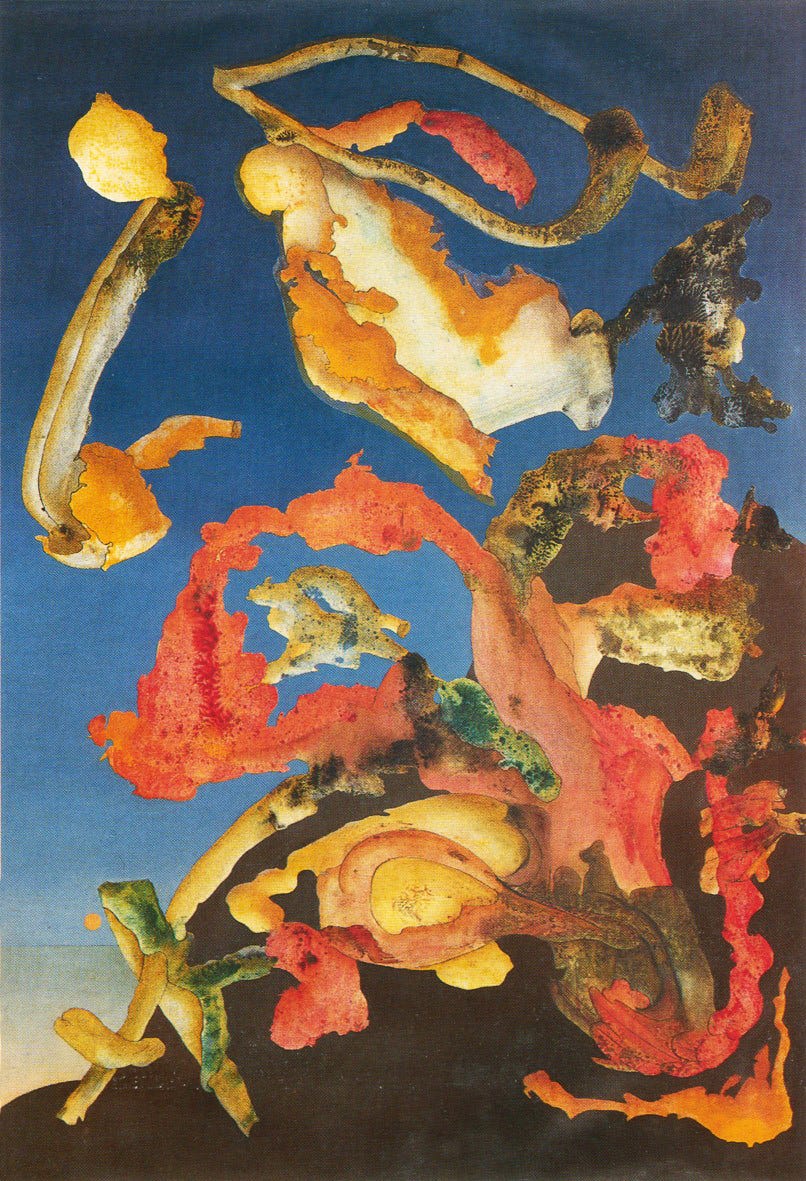

the Gorgon, her guts and a fly

The technique of decalcomania consists of putting paint or ink (and maybe some paint thinners or other solvent) on one sheet, laying another sheet over it, agitating the two sheets a little, then pulling them apart to revealing forms suggestive to the imagination. The results of the pull (the ‘stains’) can then be worked up and ‘hinted’ by the artist working on it to draw out and suggest to others what they had seen.

sickly-organic textures, evoking… rotting flesh, collapsing architecture and moral decay

Some kind of decalcomania or frottage (or both) is used in Max Ernst’s Europe After the Rain II (1940-1942), creating sickly-organic textures, evoking the rotting flesh, collapsing architecture and moral decay Ernst saw in a vision of the ruin of post-war Europe inspired by decalcomania. Colquhoun repeatedly drew on the technique from the late-30s on to make striking paintings: bold, energetic, cryptic.

In The Gorgon (1946) Colquhoun creates a decalcomania-derived image with the same form as in Guardian Angel (1947) and Moment of Death (1946): “I meant to paint a ‘guardian angel’ but the result of the automatism was so horrific that I had to call it a Gorgon instead.”22 In Greek mythology, the Gorgons were three daughters of the primordial sea god, Phorcys, so terrible that anyone who looked on them turned to stone (note the themes of the sea, represented by Phorcys, and of petrification again, as in Scylla and Goufres Amers).

metastasising fallopian tubes, or organic forms being spilled out from the main body.

Of the three Gorgons – Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa – only Medusa is mortal. She is killed by Perseus with the help of Apollo and Athena. But we have no evidence as to which of the three sisters graces the painting.

For Freud, the image of these lethally irrascible Gorgons was a projection of the castration anxiety induced when a boy first sees a woman’s genitals complete with pubic hair, so the Gorgons’ snake-hair is a compacted image of penis and pubic hair together. Is pubic hair suggested by the dark flashes on the inside of the Gorgon’s ‘wings’: in that case, the central red vertical is a spine or a vulva, and the yellow forms around it could be metastasising fallopian tubes, or organic forms being spilled out from the main body.

In Colquhoun’s image, the colours are vivid (and presumably aligned with her evolving colour theory) but the image overall is so abstract it is hard to read with certainty. No obvious unifying concept emerges. There are no ‘signs’ to read, just a mass of maybe organic matter. Take time to make your own entertainment at this point. As you do so, boundaries blur like the Gorgon’s hair – petrific snakes reduced to whispy, sinuous smoke up top of the image.

Some see feathery wings on either side of the image, opening, or being blown apart; Richard Shillitoe saw “fallopian tubes; ovaries; a cloaca spewing eggs; strings of viscera; sliced putrefying fruit, a breeding ground for spores and other accretions encroaching from the edges”;23 I saw something similar, coming together to form the head of the fly from Rupert Hooke’s epochal hymn to the microscope, Micrographia (1665), a book which is genuinely surreal in the beauty of its visual contrasts and disjunctions. If we see so far it is because we stand on the shoulders of giants.

With detailed anatomical studies on the syllabus at the Slade, Colquhoun may have seen this herself.

Automatic methods make art in a double movement

In her talks and writings, Colquhoun gave grounded, practical descriptions of how she used decalcomania essentially to suggest things to the creative mind, which picks up on the suggestion and turns it into an artwork. The mantic suggestion becomes the basis of a painting. Thus, automatist methods create art in a two-part movement. First comes the randomly-marked surface (stain) or randomising process which prompts in the artist a vision (↦ reception); the artist then works on the surface again to enhance, concretise and manifest the vision (by inscription ↦).

This is all very well, but it may be a little misleading as a description of Colquhoun’s practice at times, in which whatever was imposed on her mind as a result of the decalcomania pull was not necessarily that forcibly projected back onto the canvas. The inscription phase can be heavy, to the point of obscuring the chaotic origins of the image, or it can be so light as to offer no interpretive guidance at all. Colquhoun’s work is often at the latter end of that scale, though she was clearly willing also to step in when the work required it. She explained that automatism “may proceed along lines of complete abstraction... or there may be a hint of natural objects which can be organised and intensified into a design."24

She takes issue with tthe Romanian Surrealist, Dolfi Trost (1916-1966), who would “not admit of the interpretation of automatic deliverances, [and stigmatises the interpretation of automatism almost as a deadly sin, calling it equivalent to an absurd intervention in the mechanism of universal causality.”25 Colquhoun counters non-dogmatically that she “is inclined to think that the best results will be obtained from interpreted automatism.”26 But her practice regularly veered toward Trost’s implied ideal of non-intervention and Ahimsa.

If you visit the exhibition, it is curious to see Colquhoun’s image, Attributes of the Moon, alongside the corresponding decalcomania pull sheet preserved in her archives (you can do the same with her Battle Fury of Cuchullin and its corresponding pull sheet, both also at the exhibition). The final image is of an abstract form, with features identifying it (given its title) as a moon goddess or lunar spirit. Significant work has gone into turning what must originally have looked something like the remaining pull sheet into a definite figure with identifiable attributes.

What struck me is how the pull sheet much more closely resembles, for instance, the stunning enamel abstractions she was painting twenty years later. It’s as if she learned slowly to reduce the weight of the inscription phase of the automatic process. Such a reduction may reflect a corresponding ability on her part to loosen the event horizon of her ego to allow other entities and personas to jump over the border to speak through her. In such images, she directs her art to viewers that can do the same, creating a collective hallucination.

Animistic dissolution of the ego moves the authorial locus from the canvas out into the space between it and the viewer

The abstraction of so many of her automatic paintings reflects her implicit faith in the power of her irritant materials to invoke visions, and not only in the artist. It can only be a matter of degree, but having loosened the boundaries of the self to achieve her inspiration, Colquhoun also slackens the grip of the authorial voice by coauthoring her visions rather than only broadcasting them. This gift to the viewer of joint authorship is part of the occult promise of Surrealism (“Marcel Duchamp claimed that one half of each surrealist work was made by the artist and the other half by the onlooker”),27 but Colquhoun’s greatest abstractions truly put the viewer in the driving seat.

By contrast, Dalí’s images, certainly those of his later years, sometimes almost seem to parse themselves on your behalf into the equivalent of a pun, a slip of the tongue or a slogan, as with Magritte’s painting. What is it that makes Colquhoun’s painting a painting of the head of a Gorgon? The title does some heavy lifting, prompting us to solve the visual koan, but to that extent the painting ceases being the record of a vision, to become instead a machine for manifesting minds, in which the viewer fully participates and to which they contribute (if they can). Animistic corrosion of the borders of the ego shifts authorial focus away from the canvas into the space between it and the viewer: in this way, the paranoiac potential of the Dalí painting is multiplied.

What is that something else?

To grasp Colquhoun’s relation to standard Surrealist automatism, first you need to know that all sides agreed that the purpose of automatism is to relax the grip of everyday mind so as to let something else to speak in its place. But what was that something else?

For the Surrealists, steeped in Freud, their default answer, the unconscious, was something of a catch-all, requiring further unpacking by Lacan and others since, but already carried with it floods of Freudian grace notes and hints for further unpacking of what it produced. Colquhoun agreed that it was indeed usually the unconscious being roused to speak, and even that it spoke much as the Surrealists described, but she believed in addition that the properly prepared unconscious could channel other intelligences – of greater or lesser autonomy and independence from oneself: spirit intelligences, Earth magic, genius loci, daimons and divinities.

she believed that the properly prepared unconscious could channel other intelligences

To say as much is not to deviate from Surrealism, but to enrich and expand it. And in the years after Colquhoun’s introduction to Surrealism, and after she left the British group, many Surrealists internationally, including Breton, came around to something like her view of occultism. The view that Colquhoun was too spicy (‘alterior’) for Surrealism to deal with is a distortion spun out of Colquhoun’s deeply attractive intransigence and determination.

spiders on the universal web

I rest not from my great task!

To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes

Of Man inwards into the Worlds of Thought: into Eternity

Ever expanding in the Bosom of God. the Human Imagination

William Blake, Jerusalem28

Breton’s first take on automatic writing not only did not consider the occult; it sniffed a bit and ignored it, as it was associated with middle-brow spiritualism. As one biographer of Surrealism, Ruth Brandon, put it: “… the technique Breton and Soupault picked for their experiment in automatic writing would seem to indicate the influence of Janet as well as Freud, for he was a leading light of the spiritualist movement, and this was a technique frequently used by spirit mediums in their attempts to contact the dead... [But] the automatic writing of spirit mediums produced little of interest... Breton and Soupault, however, proposed to apply this technique with Freudian rather than occult intent.”29

It is true that when reading some Surrealists on the ego and unconscious it sounds as though the unconscious were as constrained and localised as the ego it is attached to, albeit that it contains marvels due to its not being rationally, discursively or imaginatively constrained. These marvels supposedly fit in a small space at the back of the head.

In truth, while the ego is usually locked down, the unconscious is open for incoming calls, and plugged into a network (ourselves) which achieves seamless connectivity to the remotest of things by not separating from them to start with. The unconscious squats in the semiotic gloom like a spider on the universal web. The conscious quarter of the mind is hypnotised by the strobe lights above, while the unconscious twin looks down, awaiting twitching on the wires.

Like a limpet on a volcano, however, the unconscious rests on a free, freely-available, and infinite source of energy, the esemplastic imagination, the totality of Mind, in relation to which we are all just bobbles of wool caught on the heel of the great cosmic sock: the “Human Imagination”, as Blake put it, is “the Divine Body of the Lord Jesus, blessed for ever.”30

In the course of development of Surrealism, the older stance toward the occult was abandoned, particularly after Breton’s Prolegomena to a Third Surrealist Manifesto, or Not (1942). Brandon writes: “In later years, Breton would become increasingly interested in aspects of the occult astrology, for example, or the clairvoyant talents of mediums, weapons in his continuing war upon logic and lucidity, the twin enemies of the marvelous.”31

departing planes

Beloved imagination, what I like most in you is your unsparing quality.

André Breton32

Colquhoun’s history as an artist is intriguing, in that the strongly affirmed independence of her views isolated her from groups, but her challenging of morals and established values and her interest in the secret lores locked deep in alchemical books, hermetic traditions and the subterranean layers of Cornish legend anticipated the surrealist’s preoccupation with arcane lore and Celtic as well as Gallic art.

Michel Remy, Surrealism in Britain33

Was she artist or occultist? It was, as she knew all along, a distinction without a difference.

Richard Shillitoe34

The spat between Colquhoun and the Surrealists was no great parting of ways. No principles were at stake. It hung more on accidents of timing and some high-handedness from an inexperienced leader, rather than different lines of march.

During the early months of WWII the Surrealists sought to tighten up their organisation to make it more coherent, preparing it to meet the tasks imposed by a global war. Consequently, in April 1940, the organiser of the London group, the gallery manager, Édouard Mesens, convened a meeting at the Barcelona Restaurant on Soho’s Beak Street, the group’s regular dining spot, to discuss reorganisation.

With Herbet Read, Roland Penrose, Edith Rimmington, Eileen Agar, Grace Pailforth and others in attendance along with Colquhoun, Mesens proposed, first, that they publically and collectively commit to the cause of proletarian revolution, and that as individuals that they should no longer exhibit other than at Surrealist events, or publish in journals other than the Surrealists’.

Most of those present agreed, as the proposals were in line with existing Surrealist attitudes, albeit now turning them into articles of membership. A few spoke against one or other of the new rules but opted to remain members of the group when the new rules were voted through anyway.

Some who discontinued their membership or were excluded because of some disagreement or other were nevertheless asked to exhibit with the Surrealists at their group show the following June. Grace Pailforth, Reuben Mednikoff and Eileen Agar were all outside the group for a while, but were eventually reconciled or even rejoined. An invitation to lunch at the Barcelona was not as fraught, conflicted or consequential as an arraignment at the Moscow Trials, two years earlier.

Colquhoun, however, stuck out by opposing all three proposals, and thereafter ceased to be a member. She was not invited to take part in Surrealist (or related) exhibitions again. This outcome was ultimately more to do with personal antagonisms and misunderstandings – the small change of small groups – than with any fundamental difference of perspective. Those seeking to minimise the overlap between Surrealism and occultism, irrespective of whether they are cis-Surrealists or cis-occultists, ignore this and play up the gulf between the two sides and the irreconcilability of the various parties.

According to monkey-whispering, man-decoding celebrity Surrealist (and biographer of many of the British Surrealists), Desmond Morris, Colquhoun “was, first and foremost, an occultist, wrapped up in the gobbledygook of the supernatural,” and so was presumably no great loss to the movement.35 On the other hand, those interested primarily in Colquhoun’s occultism sometimes imagine that it could only exist in opposition to, or at least at a safe distance from, Surrealism. In this view, Surrealism and occultism cannot permanently coexist: one must give way to the other. They may even claim, in the words of the Tate website, that Colquhoun was expelled “for refusing to renounce occultism.”36

This idea rests on nothing more substantial than a few tame, socially acceptable prejudices about Surrealist sectarianism, rigidity and (ironically) a lack of imagination. It assumes an antagonism between Surrealism and the occult which doesn’t exist in principle, and wasn’t contested as such in the split. Mesens sought bureaucratically to stop the comrades investing time and energy in non-Surrealist events and organisations, wanting to monopolise their output instead for bona fide Surrealist projects. The fact that, in Colquhoun’s case, the competing organisations were occult was not the issue. No doubt Mesens was also peeved and antipathetic toward occultism in the group, but that was his problem, not Colquhoun’s, and not a problem for Surrealism as such.

Colquhoun was not censured for wanting to depict occult themes; only for wanting to depict them in occult publications. Even then, before the decade was out she was appearing on BBC television, defending Surrealism alongside Penrose and even Mesens himself.

Colquhoun wouldn’t agree with Mesens’ requirement not to publish in other outlets, because she was determined to continue contributing to her favoured occult publications, as had long been her habit. At no point was she told to renounce occultism – that would have been absurd and pointless. Colquhoun simply didn’t accept the new rules about exhibiting and publication because she did such things routinely as part of her regular art practice and was disinclined to stop doing so. Why should she?

Colquhoun was not expelled against her wishes, but accepted separation as the price of continuing with her work. She walked away, whatever the formal situation was with expulsions and resignations. She stuck to her guns, refusing to back down in the disagreement, possibly even being secretly happy to get Mesens off her back, so she could get on with her work.

Leaving the London Surrealists cost Colquhoun in terms of opportunities to exhibit, and mainstream art recognition in the long run: “this dissociation from any official faction in British modernism led to a lack of recognition and… her exclusion from dominant art historical discourses.” (Katy Norris).37 You could say of Colquhoun what was once said of the saxophonist, John Gilmore: like Gilmore, she “abandoned the spotlight of personality for the sunshine of art.”

What about her opposition to the proposal declaring for the proletarian revolution? Was she a reactionary? Katy Norris says that she “was not involved in any direct campaign for sociopolitical change; rather, she was interested in enacting a fundamental shift in consciousness via the process of spiritual self-actualisation and enlightenment.”38 This is true, biographically speaking, but there is no evidence that she counterposed magic and politics this way at the time, or that that is why she opposed Mesens.

Speaking against Mesen’s proposal to commit to proletarian revolution, Colquhoun argued against accepting any formulation without clear implications for action and agitation. She may have been underplaying political differences here, emphasising what the two sides had in common for the sake of argument: but what she did not do was to contrast the life of the spirit with life as such, with its politics: she did not choose the first path in preference to the second.

She obviously was not what today you would call an activist, but he made political art in future, supported political agitation at times, and certainly didn’t reject politics as such – see, for example, her painting E.L.A.S. (1945), commemorating the massacre of Greek communist demonstrators by British troops; not only political, but militantly so.

Surrealism’s authentic domain encompassed the occult as a manifestation of the primal imagination, the esemplasm

While the issue of not appearing in other publications was only tactical at best, and the political disagreement was not pressing (because, as Colquhoun argued, it had no practical implications), the outcome of the disagreement was nevertheless Colquhoun’s separation from the Surrealist group, with a resulting loss of opportunities to exhibit and, ultimately, her disappearance for a while from mainstream accounts of Surrealism.

But this doesn’t imply a slackening of Colquhoun’s commitment to Surrealist and automatist principles – a fact to which the images throughout this post, mostly created in the years after the split, bear incontrovertible witness.

Amy Hale argues that, while Colquhoun’s “contributions to Surrealism are notable, her relationship to the somewhat emergent category of esoteric art was perhaps more profound and enduring, especially since her Surrealism was always in service to her esoteric and occult focus.”39 But this turns Surrealism into a matter only of technique, which it most certainly cannot be reduced to (“Surrealism is not merely a new aesthetic; it is a mode of knowing, of living.")40 Surrealism is not a means to an end, the marvellous, but the end itself, in its unitary embrace of the marvellous.

Colquhoun would have understood that Surrealism’s turf encompassed the occult as a manifestation of the primal imagination, the esemplasm. She oriented herself with a disciplined Surrealist instinct for the marvellous (alongside her occult intuition for the integrity of the whole: as above, so below) in her occult workings, which is not the same as simply performing an occult ritual or séance or rite as such, hence she notes that Surrealist automatism “could not be confused with the cozy platitudes delivered by the average spiritualistic circle.“41 Neither is Surrealist art an artistic embellishment of the occult main event: the resulting artwork is a magical object itself. Surrealism fully inhales.

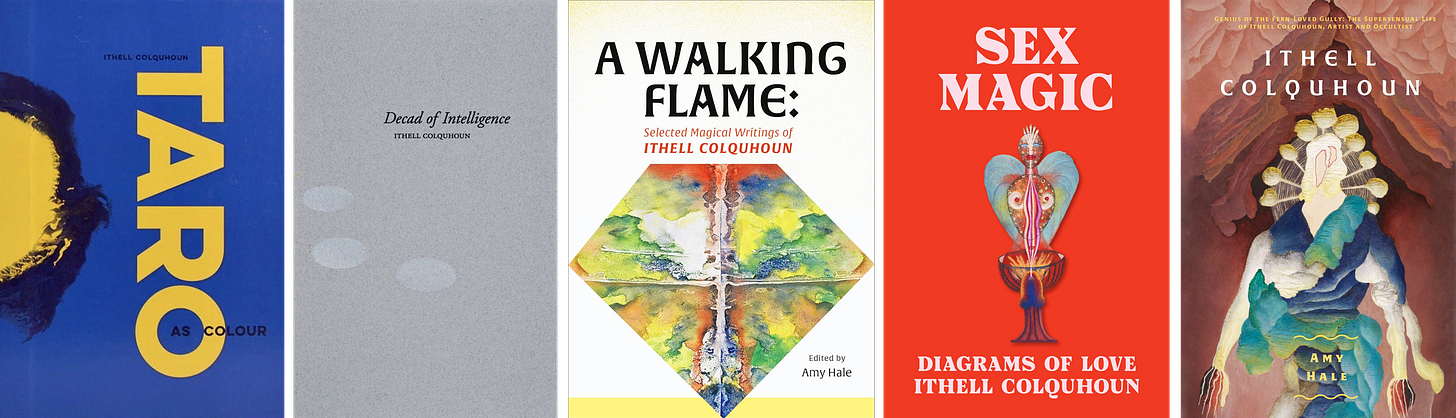

Of the main books supporting and giving shape to the revival of interest in Colquhoun, five are from publishers specialising in the occult and occulture (Robert Shehu-Ansell’s Fulgur Press, and Mark Pilkington’s Strange Attractor), while the other (Sex Magic: Diagrams of Love), focuses wholly on a specifically occult topic.42 The books are good, and the upsurge of interest in occult art generally is to be welcomed on its own terms: on top of that, the recognition and documentation of Colquhoun’s pioneering role within that story is especially satisfying.

Nevertheless, this resurgent interest in the occult aspects of the story should not obscure the fact that Colquhoun remained essentially a Surrealist until the end, developing her own program of Surrealist research in parallel with the official group. It was not a matter of her branching away from Surrealism into occultism, but of continuing her Surrealist researches into the occult despite her split from the London group.

Mantic Stains #3: Psychomorphology and Occult Surrealism

In 1949, Colquhoun appeared on the BBC special, Eye of the Artist: Fantastic Art, alongside Eileen Agar, Mesens and Penrose, demonstrating the automatist techniques of Surrealism: the first public presentation of automatist techniques in Britain. She showed how to use the techniques of parsemage (image below: top left), fumage (bottom left) and decalcomania (top and bottom right).

Her explanation of what she was doing was lucid but intensely practical in its focus. Her script for her part in the program was written up as The Mantic Stain (1949), then reworked as Children of the Mantic Stain (1951). In the latter text she talks at length about how a teacher could use Surrealism in the classroom, imposing only one rule on the process: “in encouraging the interpretations of the stain no censorship of any kind should be imposed, and each pupil… should feel entirely free to explore new territory.”43

The term ‘mantic’, from the Greek mantikos, refers to the divinatory and prophetic – in this case, the ability of automatism to provide materials for scrying and divination (thus she names her vision of Surrealism after this ‘occult’ practice). A related Greek root, mainesthai (‘to be mad’) provides the source for our word ‘mania’: how apt that Colquhoun’s preferred term should capture both the enlightening (prophetic) and the convulsive / maniacal aspects of the Surrealist aesthetic together.

Similarly, Colquhoun speaks repeatedly of ‘psychomorphism’ as her term for what lies on the other side of the automatist experiment: “the discovery by various automatic processes of the hidden contents of the psyche,”44 both personal (psychological) and transpersonal (occult). It could as easily be called ‘psycho-topology.’ This is her version of a term she’d picked up with the Surrealist research group in Lyon, in 1939, specifically to refer to an expanded sense of the possibilities of automatism.

This is the non-natural domain of Surrealism I alluded to earlier, its interior spaces brought into view by psychomorphology in an adventure combining, at a bare minimum, Jules Verne’s 80,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Lewis Carroll’s Alice and The Hunting of the Snark, The Ripley Scroll, Little Nemo, Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Finnegans Wake, Krazy Kat, and the Interior Castle of Saint Theresa of Avila.

some final mantic stains cleared up

Rather than analyse her argument, which has anyway been touched on earlier, it is better to let Colquhoun describe the gist of her attitude:

“The principle of all these processes is the making of a stain by chance, or ‘objective hazard’ to use the surrealist term, the gazing at the stain in order to see what it suggests to the imagination and, finally, the developing of these suggestions in plastic terms…

The development of the initial stain may proceed along lines of complete abstraction, in which case the resulting shapes will not recall anything seen in nature. Although there may be a hint of natural objects which can be organized and intensified into a design. Or, again, a treasury of symbolic scenes or ‘mind pictures’ may be dredged up from the depths of the fantasy life, that dreamworld of which many are hardly aware in waking consciousness. That is, in the first instance a ‘non-figurative’ work will result; in the second and third, figurative works whose provenance is, respectively, external and internal reality…

I'm inclined to think that the best results will be obtained from interpreted automatism, though it is obvious that the mere making of the automatic stain will have an immensely liberating effect in many cases.”45

Colquhoun describes techniques such as the decalcomania described above already (“invented by the Surrealist painter, Óscar Domínguez,”)46 but also frottage (rubbing of irregular surfaces on paper), écrémage (skimming of chalk and charcoal from the surface of water), fumage (smoke trails on paper), her own paresemage technique (scattering charcoal on paper), and an approach to collage “consist[ing] of the cutting out from their context of heterogeneous visual elements and then recombining them automatically to form a new synthesis without any rational intent."47

a treasury of symbolic scenes or ‘mind pictures’ may be dredged up from the depths of the fantasy life

Children of the Mantic Stain describes the possibility of an extension of automatism (‘psychomorphology’) into the occult, projecting the Surrealist exploration of the unconscious beyond the boundaries of the practitioners’ psyche, letting the artist access occult ‘others’ on account of the trans-personal valency of the psyche, its power to hear others.

This was what she had learned when she attended a gathering in 1939, at a château outside Lyon, of younger international supporters of Surrealism, including Esteban Francés, Roberto Matta, and the British painter Gordon Onslow-Ford. There the group explored automatism, but extending it to explore mystical aspects of the world beyond the mind. Ford and Matta were influenced in this by the ‘hyperspace’ concepts of Charles Hinton, author of the ‘scientific romance,’ The Fourth Dimension, and P.D. Ouspensky, in Novum Organum.

Katy Norris summarises Colquhoun’s position: she “expressed her interest in mining the creative potential of the unconscious… at the same time she made direct links between… spontaneous surrealist processes and the elemental forces of earth, wind, fire and water that are central to natural philosophy.”48 In a nutshell, attenuation of the ego and the boundaries of the self in occult practice allows other voices to manifest through some sort of transduction or sympathetic vibration in the unconscious.

And although there is no time here to go into it, it’s worth noting that the condition of opening Colquhoun’s unconscious to the occult was the dissolution of the ego, and that she was far from being the only Surrealist interested in such a fracturing and undermining of the ego.

Many would be familiar with such things through their reading of Freud, but others, like André Masson, sought to capture such states into their art. In his case, his images often show the individual psyche as fragmented, mingled with other beings, or with the Earth and environment.

⚭ SEX ⚭ EARTH ⚭ COLOUR magic

The alchemists like to dwell on the process of creation… the object of religious worship is regularly to be regarded as a symbol of the libido, that psychological goddess that rules the desires of mankind and whose prime minister is Eros.

Herbert Silberer, The Hidden Symbolism of Alchemy and the Occult Arts49

Here is a dove, a swan

A link leading the tribe of cats

The garden with clover

Honey, a grove of myrtle

An apple tree, the opening flower of a rose

Benzoin, red sandalwood, the soft odors

I gave him the drug damiana, drink!

The image of a doorway

And all enclosed in a girdle

Ithell Colquhoun, Love Charm I 50

some diagrams of love

From the outside it may seem that Colquhoun’s different occult interests (sex magic, earth magic, divination, druidism, etc.) are distinct concerns, if related and overlapping in ambience. From Colquhoun’s point of view, however, they must be understood as different faces of the single occult reality with which she had always been concerned, and which she had learned how to work with as a Surrealist.

If I have any criticism of the current exhibition, it is that the concern to recognise and celebrate Colquhoun’s achievements in several distinct schools of occult practice as well as her achievements as an artist, might leave the impression precisely of a series of different interests or traditions that she ‘straddled’ or ‘fell between’, as the subtitle of the exhibition seems to emphasise (‘Between Worlds’). To accept such an argument, if that is what is being argued, would be to lose the necessary sense of the integrity of her work, whatever the theme, topic or medium.

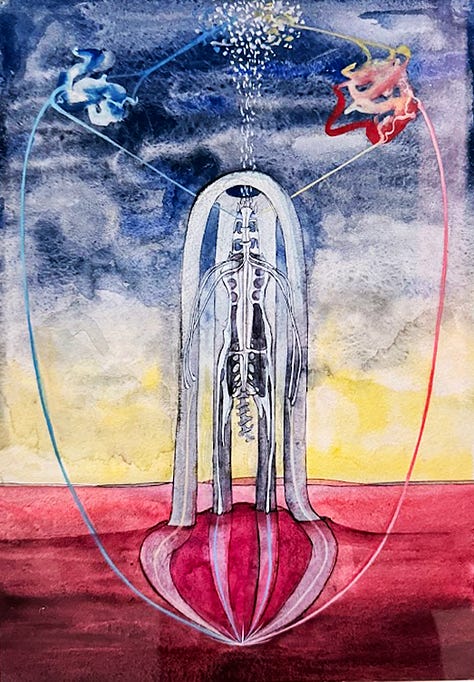

For instance, from her first engagement with the Surrealists in 1939, for the next few of years, as World War erupted across the continent, she wrote poems about, and illustrated, esoteric and occult aspects of sex, fusing alchemy and colour theory with tantric ideas about the hidden channels of energy flowing throughout the body, crossing at the vital points within the body, the chakras. Her purpose was to explore the promise of sacred sexual union.

She meditated on sex and gender roles. At one point she announces that “there are thirteen main openings in the female and twelve in the male, and the greater number present in the female body may indicate a more highly-evolved and specialised structure than that of the male.”51 A notable feature of Colquhoun’s sex magic art is that it repeatedly shows women together sexually, demonstrating elemental energies and relations.

Although Colquhoun was married for a while, lesbianism was part of her sexual identity. Her unpublished poem, Lesbian Shore, was based on the infatuation she felt for a female acquaintance, Andromaque Kazou. In the sex magic work she certainly considers it possible that the road to divine sexual bliss might lie in sex between women.

The work consists of two bundles of texts and images. One, Diagrams of Love I, explores themes of physical and sexual connection and union. The other, Diagrams of Love II, explores the same union, but intercut with themes of loss, doubt and despair. The visual work of both sets is dominated by:

depictions of the clash of elemental fire and water

depictions of the flow of blood and of energy

scenes depicting aspects of the sacred marriage of the King and Queen, which creates the Divine Androgyne, the union of spirit and matter.

As art, some of the images fade off into the style of those tidy theosophical illustrations and tables itemising all the properties of stones or decades or phases of the moon, yet it is hard to exaggerate their historical significance from an occult point of view. As Amy Hale notes, her work “is likely the earliest sustained and explicit visual expression of a sex magic program associated with Western magical subcultures, and it was created by a woman.”52

Not part of the sex magic collection, but surely related, is the folder of sheets, each of which, with only one exception, contains a single black and white image (the exception shows a stick of lipstick.) These were prepared as what is assumed to be a storyboard for the planned Surrealist film, Bonsoir (1939), but there is no accompanying script or storyline.

The bare outline of a story that can be inferred from the images is of a wealthy couple’s night out, disturbed by the interaction of the woman in the couple with another woman she meets in the course of the evening. I think the images as they are have a spare lyricism which is underestimated, as can be seen if you assemble them into a collage, and compare them with Dalí’s collage, The Phenomenon of Ecstacy from a year earlier (though I doubt there is any influence there).

shake your foundations

Another theme emphasised by the exhibition, taking place in St Ives, is Coquhoun’s absorption in the earth mysteries and antiquities of Cornwall. Coquhoun first took a small place in West Penwith, Cornwall in the 40s, from where she would commute back and forward to London to continue to support her efforts in the art world. In the 50s, however, she began to settle there and to separate herself further from the art world.

Coquhoun became fascinated by local neolithic sites and other antiquities, exploring the energies latent in the stones, and the myths about them told by the locals. She also became increasingly interested in Celtic culture and Druidism. The Cornish tourist board and the Tate are keen to play up this connection, of course, but there is a real sense in which, despite her deep love of the region, her interest was not in Cornwall as such but in the access its antiquities gave her to primal energies.

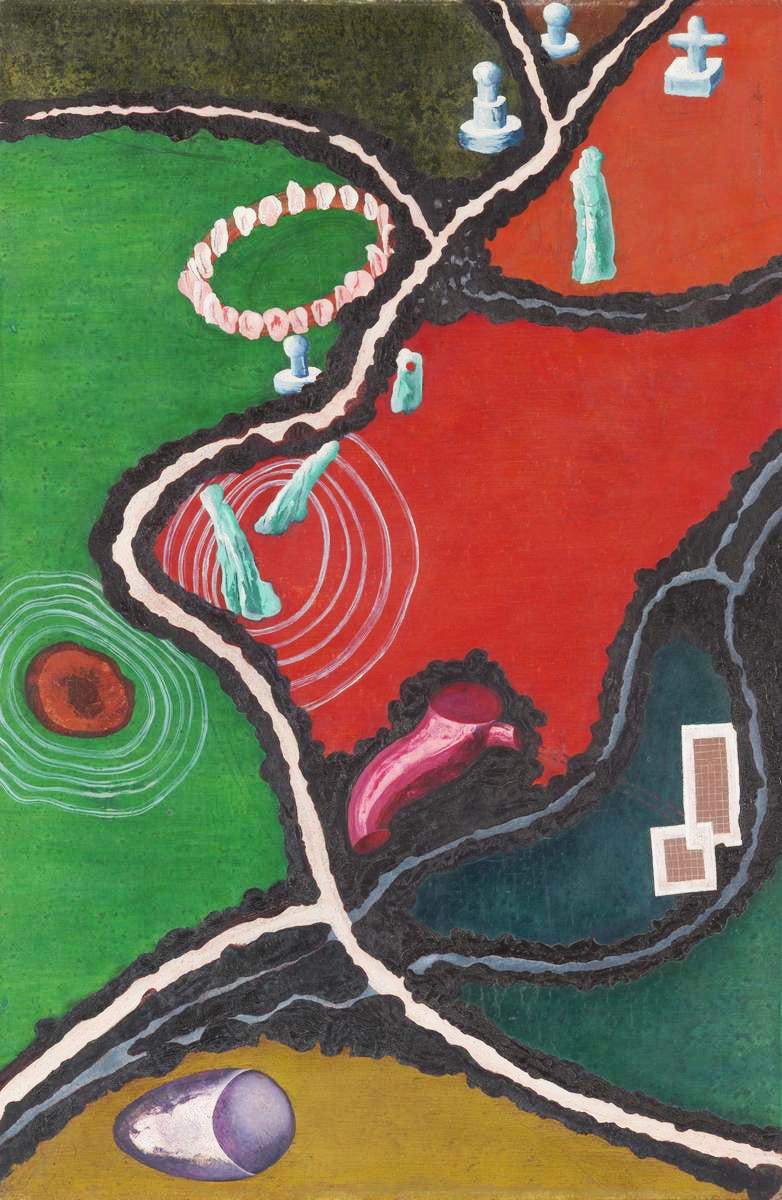

Crucially, while these energies may have been local phenomena, they were not merely regional autonomous energies. They intersect and are coextensive with the other ‘occult’ energies which absorbed Colquhoun’s time. To see this, consider Sunset Birth (1942), painted toward the end of the Diagrams of Love period. It shows the Mên-an-Tol (‘stone of the hole’) standing stones, a short way from her Cornish home.

The three stones – two vertical, the other, known as the ‘Crick Stone,’ circular – once stood at the centre of a late neolithic stone circle, the outer parts of which are now gone. It’s known that the remaining three stones were realigned in recent history. Locals have long attributed healing power to the stones, especially the Crick Stone.

At first glance, what we see in Colquhoun’s painting are the three Mên-an-Tol stones, coloured from left to right as blue, red, and yellow. At the same time, we see bold red and yellow lines of energy rising from a node in the ground beneath the stones to embrace them. Everything thus far fits with the image we may have of ‘earth energies’ and the like.

At the same time, the title of the painting is Sunset Birth, which reminds us that it got the name because local lore said that a woman’s infertility could be cured by her passing through the Crick Stone. It becomes clear that what at first looked like faint skeins of energy in blue and red, circling between the two vertical stones, passing through the Crick Stone on their way, in fact correspond to a body.

All becomes clear when you see the first study for the painting, which shows a woman strung out between the two vertical stones, her hands clasping the stone above while her feet try to grip the one below, and the Crick Stone encircles the woman’s pelvis. In the final painting, the woman had evaporated, leaving the traces of her vital energies in circulation, the channels (nadi) that Tantra sees circulating in the subtle body. The imagery clearly has to do with the working of the stones’ magic on the woman.

But note exactly where the personal energies of the patient intersect with the external, earth energies – at the chakra points in the pelvis, the navel and the breast, where the individual’s vital energies themselves cross over. In other words, what we have in the painting is a representation of an occult reality in which the supposedly separate energies of earth and individual are shown to be wholly commensurate and in communication.

colour theory:

colour as thing:

colour intelligences

… Colquhoun's relationship to colour theory, in which she was interested from early in her formal arts training. In the 1930s she studied at the London atelier of Amédée Ozenfant, who spearheaded scientific colour theory in Britain, particularly concentrated on the effects of colour in architecture. Colquhoun's own studies of colour theory were underpinned by her interest in the Golden Dawn magical system and reinforced for her the idea that colours hold the power to communicate both concrete and more ineffable spiritual principles. Similarly to the theories put forward by Kandinsky in his 1911 text Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Colquhoun believed that colours were themselves intelligences and gateways to other planes of experience.

Amy Hale, Decad of Intelligence53

I want to finish by mentioning some late works of Colquhoun’s, united by their extraordinary use of colour. Colquhoun took colour extremely seriously, believing colours not merely to be suggestive to us of certain feelings, but actually intelligences in their own right, vehicles of subtle spiritual essences.

I don’t know enough about the theories to comment reliably on how Colquhoun deployed them, but she drew on a range of art, hermetic and occult ideas, including those of Kandinsky, concerning colours and the relations between them, alchemy, and ideas of the Goden Dawn, particularly in association with the Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck.

The first project to mention in this regard is, probably not coincidentally, her own Taro designs, which broke completely with the pictorial tradition of tarot, stemming largely from the Marseilles deck.54 Indeed, Colquhoun broke with pictorial tradition entirely, using only swirling, colliding colour. Colquhoun has created deck that speaks only in the language of colour, with no other symbolism. The colours and their relations reflect the attributes of the corresponding card.

In December 1940-41, waiting for a ship to take them from Marseilles, escaping the advancing Nazis, to the New World, André Breton, René Char, Max Ernst, André Masson, Benjamin Péret and comrades created the Surrealist tarot deck. They rejected traditional courtly themes for more modern heroes: Hegel, Freud, Lautreamont, Lewis Carroll’s Alice, and so on. The wands, cups, swords, and discs suits were replaced by flames (love and desire), wheels (revolution), stars (dreams) and locks (knowledge).

The Surrealist deck is a tribute to tarot and also a gentle mockery of it. Colquhoun’s Taro, by comparison, draws on a range of traditions, especially that of the The Golden Dawn, to create the card system, its trumps, and so on, but what is so radical is her confidence in focusing entirely on colour to depict the characters in her system. She used enamel to achieve the striking and vivid colours and colour contrasts.

After this, Colquhoun began creating similar images to illustrate the properties of the ten sephirot of kabbalah, working with enamel on larger cards that, once again, were accompanied by texts explaining the relevant properties of the sephirot, considered as divine emanations. Most of her explanations at this point are taken from Aleister Crowley.55 These works were collected together as Decad of Intelligence.

The Taro and Decad of Intelligence cards all use the same approach to distributing their colours, with the colours emerging from a center and assuming a more or less bounded oval shape.

Some of Colquhoun’s most effective later paintings use diluted enamel again to paint natural scenes in great slashes of colour, bursting with protean energy, with automatistic touches, and the patterns created by the random running of the paint. These include Volcanic Landscape (1969), Crater’s Edge (1970) and Haunted Hedge (1970), but also the spectacular Dust Devil (1969).

Her process in making these images created for her a balance between the aleatory and the conscious control of the artist that she could control and negotiate, since, as Richard Sillitoe notes, “its use enabled her to paint ‘semi-automatically’ and establish a close correspondence between her technique and her subject. With the paper or board placed flat, she was able to pour, stir and tilt, encouraging the fluid paint to puddle or flow.”56

The resulting images were among the last great flourishings of an extraordinary artist, who, far from falling away from Surrealism, continued to defend its autonomist principles, extending them into new worlds as part of the ‘occultation of Surrealism’ Breton called for as the counterpoint to the madness of World War as it descended upon them.

Andy Wilson

iii-2025

Of the range Colquhoun’s esoteric interests and commitments, Amy Hale notes: “She participated in various Hermetic orders such as the O.T.O. and a Golden Dawn-based group; she was well read in alchemy, practised Druidry, Freemasonry, Martinism, sacred geometry, earth mysteries, and ultimately Goddess spirituality. Her interests in alchemy and Kabbalah are evident in her artistic work from a young age.” Amy Hale, ‘Introduction’, Ithell Colquhoun, Decad of Intelligence, London: Fulgur Press, 2016, pp1-2.

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘The Water-Stone of the Wise’, originally in Alex Comfort and John Bayliss (eds), New Road 1943, Billericay, Essex: Grey Walls Press, 1943; collected in Ithell Colquhoun, Richard Shillitoe and Mark Morrisson (ed), Medea’s Charms: Selected Shorter Writings of Ithell Colquhoun, London and Chicago: Peter Owen Publishers, 2019. pp219-20, p219.

“She saw herself occupying a transitional spiritual space between Eastern and Western cultures.“

Katy Norris, ‘Introduction’, in Katy Norris (ed), Emma Chambers (contributing editor), Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds (exhibition catalogue), London: Tate Publishing, 2025, p11.

Ithell Colquhoun, ’A Canvas in the Wind’, in Colquhoun, Shillitoe (2019), pp258-64, p259.

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, London: Thames and Hudson, 1985, pp181, 143.

Gyorgy Lukács, Tactic and Ethics, 1919, quoted in Daniel Lopez, ‘The Conversion of Gyorg Lukács’, 2019-01-19, Jacobin, jacobin.com, accessed 2025-02-28.

Possibly the androgyne symbolised sexual liberty: “Blake follows Boehme, the Kabbala, and the tale of Aristophanes in the Symposium in presenting the androgynous human body as a symbol of libidinal freedom. Discrete sexual identity is seen as the freezing up of a free flow of.” Morton Paley, Energy and the Imagination: A Study in the Development of Blake’s Thought, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970, p69.

André Breton, Zack Rogow (tr), Anna Balakian (intro), Arcanum 17 (1944), Los Angeles: Green integer, 2004, p81.

Nadia Choucha, ‘Occultism in the Nineteenth Century’, Surrealism and the Occult (1991), Oxford: Mandrake of Oxford, 2016, p14.

Salvador Dalí, ‘Derniers modes d'excitation intellectuelle pour l'été 1934’, Oui 2: L'Archangélisme scientifique, Paris: Denoël / Gonthier, 1971, p40.

Mark Polizzotti, Why Surrealism Matters, New Haven and London, 2024, pp62-63.

David Gascoyne, ‘Recuperation’, in David Gascoyne, Roger Scott (ed), New Collected Poems, London: Enitharmon Press, 2014, p92.

Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, Surrealism, first published by Faber and Faber (1936), reissued by John Dickens & Co, 1971

The following papers and talks prepared for the 1936 exhibition are collected in Herbert Read (1971): André Breton (‘Limits Not Frontiers of Surrealism’), Hugh Sykes Davis (‘Surrealism at This Time and Place’), Paul Éluard (‘Poetic Evidence’), Georges Hugnet (‘1870 to 1936’). David Gascoyne wrote the first Surrealist poem published in Britain:

there is an explosion of geraniums in the ballroom of the hotel

there is an extremely unpleasant odour of decaying meat

arising from the depetalled flower growing out of her ear

her arms are like pieces of sandpaper

or wings of leprous birds in taxis

and when she sings her hair stands on end

and lights itself with a million little lamps like glowworms

you must always write the last two letters of her christian name

upside down with a blue pencil

she was standing at the window clothed only in a ribbon

she was burning the eyes of snails in a candle

she was eating the excrement of dogs and horses

she was writing a letter to the president of France

David Gascoyne, ‘And the Seventh Dream is the Dream of Isis’ II:3-15, New Verse #5, Oct 1933.

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘A Canvas in the Wind’ (1976), in Colquhoun, Shillitoe (2019), p258.

“Throughout her life most of her output was automatic in nature… Colquhoun’s work is full of codes and symbolic power, but it does not always provide a visual narrative, real or imaginary, that is easily accessible to the viewer.” Amy Hale, Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of the Fern Loved Gully: The Supersensual Life of Ithell Colquhoun, Artist and Occultist, London: Strange Attractor Press, 2020, p43.

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘Children of the Mantic Stain’ (1951), in Ithell Colquhoun, Richard Shillitoe (ed), Medea’s Charms: Selected Shorter Writings of Ithell Colquhoun, London and Chicago: Peter Owen Publishers, 2019, p254.

André Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), in Manifestoes of Surrealism (1972), Ann Arbor Paperbacks / University of Michigan Press, 2010, p26.

Ithell Colquhoun (1951) p245.

Austin Osman Spare and Frederick Carter, ‘Automatic Drawing’, in A R Naylor (ed), From the Inferno to Zos: The Writings and Images of Austin Osman Spare, 3 Vols., Vol. 1, Seattle: First Impressions / Mandrake Press, 1993.

Ithell Colquhoun (1951), p246.

Ithell Colqhoun, quoted in the notes to Gorgon (1946) at The Tate, St Ives, Feb 2025.

Richard Shillitoe, ‘Gorgon’, on Ithell Colquhoun: Magician Born of Nature, ithellcolquhoun.co.uk, accessed 2025-02-28.

Ithell Colquhoun (1951), p246.

Ibid, p247.

Ibid.

Michel Remy (1991), ‘Foreword’, p20.

William Blake, Jerusalem I 5:17-20, in William Blake, David Erdman (ed), Harold Bloom (commentary), The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1965), Anchor Books / Random House, 1988, p147, [E147].

Ruth Brandon, Surreal Lives: The Surrealists 1917-1945, London: MacMillan, 1999, pp158-159.

Ruth Brandon (1999), pp158-159.

André Breton, ‘Manifesto of Surrealism’ (1924), Manifestoes of Surrealism, Ann Arbour Paperbacks, 1972, p4.

Michel Remy (1999), p244.

Richard Shillitoe, ‘Ithell Colquhoun: Painting from the Hinterland of the Mind’, Ben Hunter Gallery, 2024, p3.

Desmond Morris, The British Surrealists, London: Thames & Hudson, 2022, p75.

“She was eventually expelled from the Surrealist Group after refusing to renounce occultism, a subject she became a recognised authority on.” Tate Gallery, ‘Biography of Ithell Colquhoun’, Tate Gallery, tate.org.uk, accessed 2025-02-22.

Katy Norris, (2025), p11.

“Colquhoun was not involved in any direct campaign for sociopolitical change; rather, she was interested in enacting a fundamental shift in consciousness via the process of spiritual self-actualisation and enlightenment. She believed that unseen, mystical forces had a rejuvenating power that could be harnessed by adept practitioners for the purpose of self-fulfilment and the restoration of order to human civilisation.”

Katy Norris (2025), p11.

Amy Hale, ‘Introduction’, Ithell Colquhoun, Decad of Intelligence, London: Fulgur Press, 2016, p1.

Michel Remy (1991), ‘Foreword’, p19.

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘Notes on Automatism’ (1980), in Ithell Colquhoun, Richard Shillitoe (2019), p255.

Fulgur Press: Ithell Colquhoun, Amy Hale (intro), Decad of Intelligence (2016); Ithell Colquhoun, Amy Hale, (intro), Taro as Colour, London: Fulgur Press, 2018; Judth Noble, Tilly Craig, Victoria Ferentinou (eds), The Dance of Moon and Sun: Ithell Colquhoun, British Women and Surrealism (2023).

Strange Attractor: Amy Hale, Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of the Fern Loved Gully: The Supersensual Life of Ithell Colquhoun, Artist and Occultist (2020); Ithell Colquhoun, Amy Hale (ed), A Walking Flame: Selected Magical Writings of Ithell Colquhoun (2025, forthcoming).

Ithell Colquhoun (1951), p254.

Ibid, p247.

Ibid.

Ibid, p248.

Ibid, p251.

[Colquhoun] “expressed her interest in mining the creative potential of the unconscious… at the same time she made direct links between certain spontaneous surrealist processes and the elemental forces of earth, wind, fire and water that are central to natural philosophy. She also emphasised automatism's divinatory power, which she compared with forms of clairvoyance such as crystal ball reading and scrying… Colquhoun's summation of automatic practices focused not only on the subjective expression of the interior self but the active translation of external mystic forces manifested within different temporal and spatial realms of the wider cosmos.”

Katy Norris (2025), p17.

Herbert Silberer, Probleme der Mystik und ihrer Symbolik (1914) / The Hidden Symbolism of Alchemy and the Occult Arts (1914), quoted in Nadia Choucha (1991), p138.

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘Love Charm I’, in Ithell Colquhoun, Amy Hale, Sex Magic: Diagrams of Love, London: Tate Enterprises Ltd, 2024.

Ithell Colquhoun, ‘The Openings of the Body’, in Colquhoun, Shillitoe, Morrisson (2019), p268.

Amy Hale, ‘Exploring the Magical Erotic Corpus of Ithell Colquhoun’, in Ithell Colquhoun, Sex Magic: Diagrams of Love, London: Tate Enterprises Ltd., 2024, p3.

Amy Hale, ‘Introduction’, Ithell Colquhoun, Decad of Intelligence, London: Fulgur Press, 2016, px.

She called them ‘Taro’ rather than ‘Tarot’ because she thought that better reflected what she believed were the Egyptian origins of the tarot.

“Most of these correspondences and her text are drawn directly from Aleister Crowley's Liber 777 and the Sepher Yetzirah.”

Amy Hale (2016), pxi.

Richard Shillitoe (2024), p3.

If you think about it, a mantic stain is an augury of innocence. And vice versa.