Neither Muggletonian nor Moravian but Blakean: A Critique of Keri Davies

Keri Davies is a Blake scholar, determined to dismiss Blake's radical, dissenting posture, turning him instead into a small businessman of orthodox outlook. What gives?

My point of departure was a book that I wrote called The World Turned Upside Down, in which I tried to analyse some of the more extreme ideas of the radical minority of the 1640s and 1650s. I sent a copy of this book to G. R. Elton, with an apologetic remark that it was not his kind of book, but it was what I had written. Professor Elton replied, courteously but trenchantly: “the ideas that you find put forward are awfully old hat – commonplaces of radical and heretical thinking since well before the Reformation.”

Christopher Hill1

If even such an irascible old conservative as G. R. Elton recognises that (perhaps most of) the ‘radical’ ideas put forward in the English Revolution probably had a long and distinguished past, conceivably having survived since Lollard times, then it is at least possible that they also survived the repression and censorship of the Restoration and metaphorically linked hands with the resurgent radicalism of the 1790s. If that is the case, then it is also at least possible that they influenced William Blake.

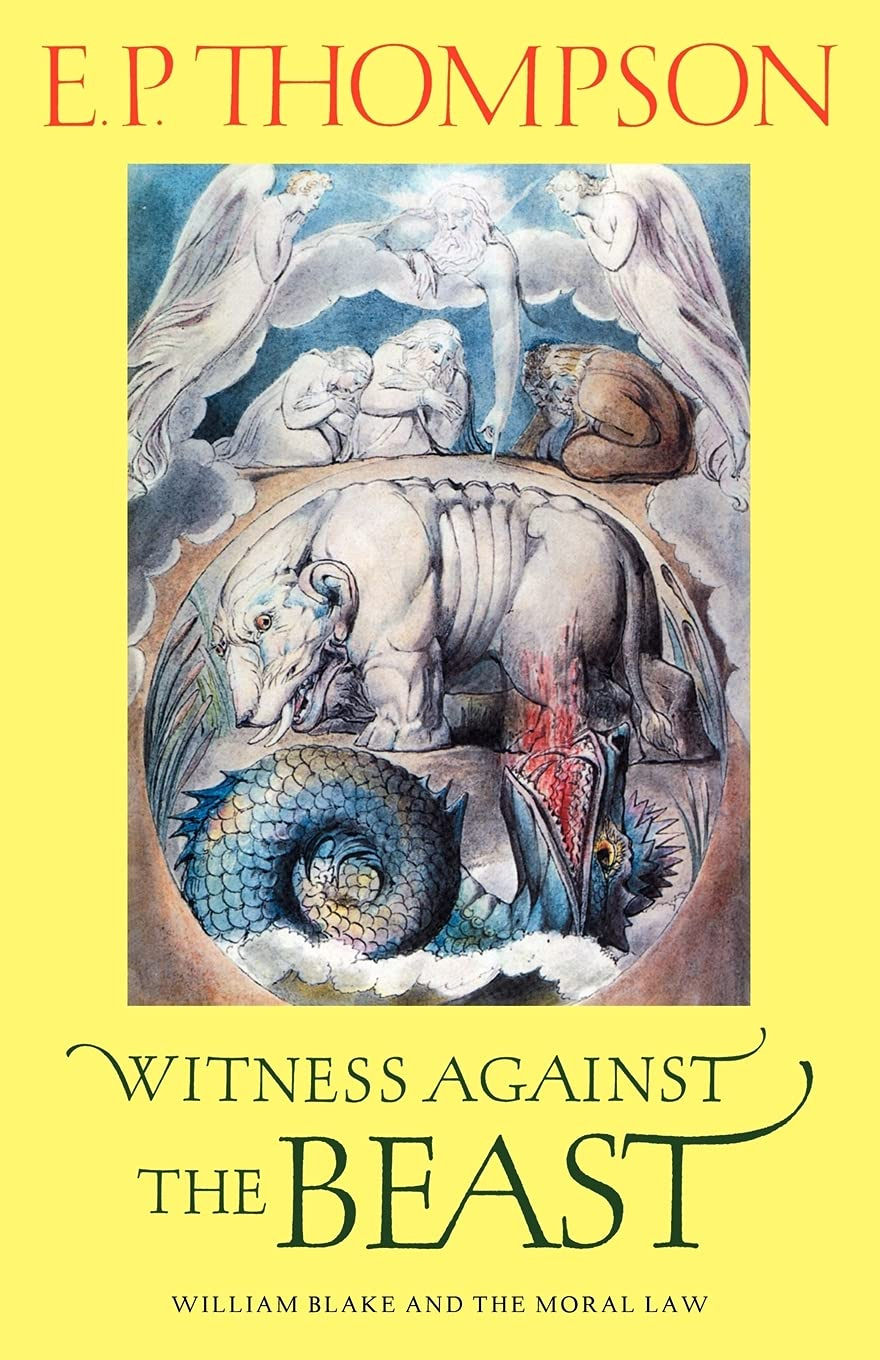

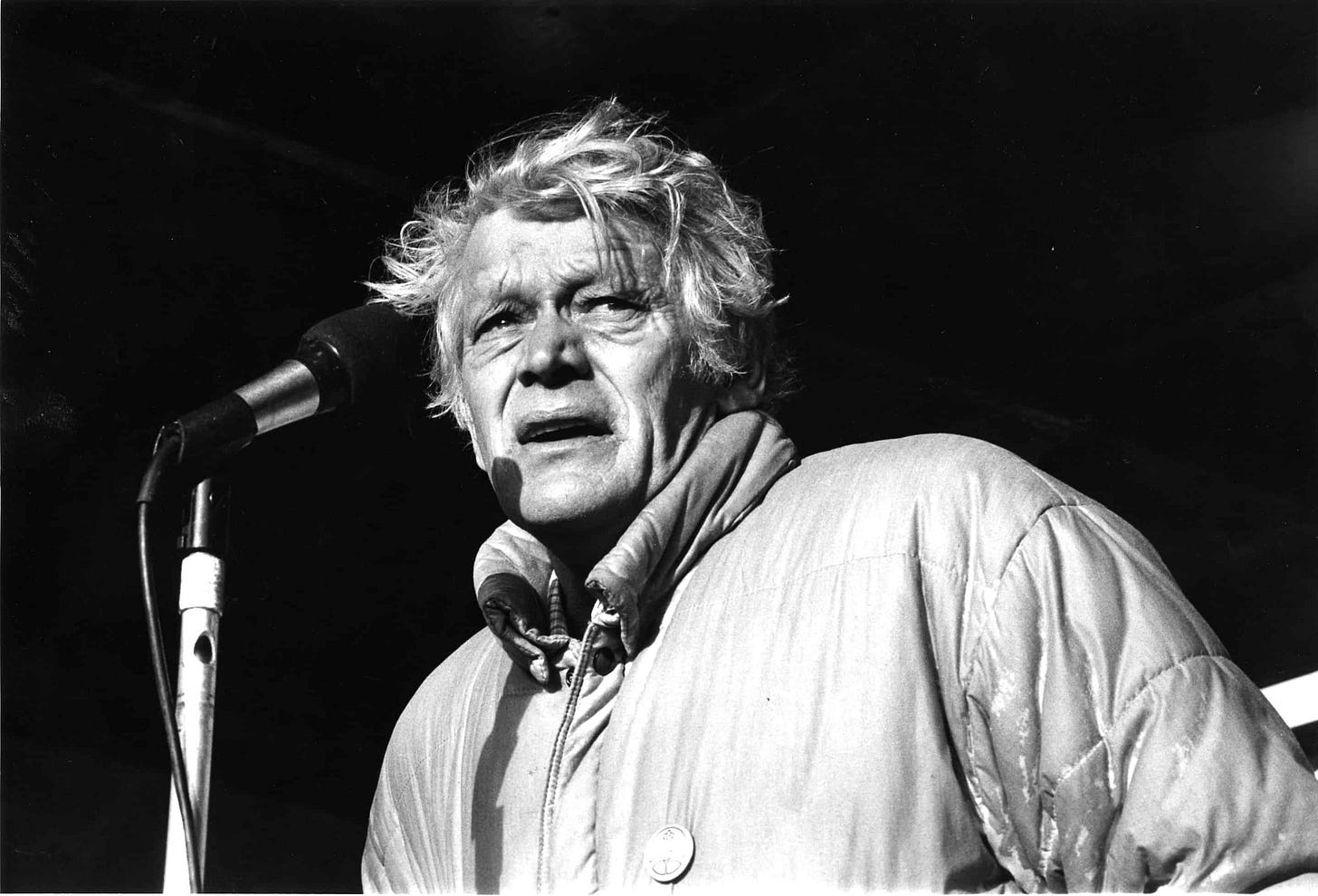

Indeed, we do know that one sect managed to survive, despite its aversion to evangelism and proselytising, until well into the twentieth century. This sect is the Muggletonians. The great Marxist historian E. P. Thompson liked to twit his audience by referring to himself as a ‘Muggletonian Marxist’, partly because of the alliteration, perhaps, but more probably because, as with him, this fiercely independent sect stuck to their ideas, refusing to be swayed by the vagaries and fashions of the times. As he said: “I like these Muggletonians”.2

Witness Against the Beast

In Witness Against the Beast, Thompson posited that Blake had Muggletonian connections through his mother who, before marrying James Blake, had been the spouse of a Thomas ‘Harmitage’ at the ‘irregular’ (meaning that it specialised in quick marriages, where no licenses were required, nor bans read) Anglican church of St George’s, Mayfair.3 As no ‘Harmitages’ can be found, Thompson looked again at the register and ‘discovered’ that the name was, in fact, Hermitage, of which there were several in the parish registers of St James, Piccadilly (Blake’s baptismal church) between 1720 and 1750.

‘Hermitage’ was the surname of a well-known Muggletonian (in so far as any were well-known) by the name of George, who had written two of the hymns in one of the sect’s songbooks, which impressed Thompson with their proto-Blakean rhetoric.4 This fitted with what Thompson saw as resonances between Blake’s work and the beliefs and rhetoric of that sect. Thus, he further suggested that those influences might have come down through Blake’s mother recounting the creed of her first husband, and possibly her own.5

There are a lot of maybes and mights in this supposed chain of influence, and one fatal misreading. To correct these and offer a more convincing account, we must turn to the work of Keri Davies: although we must also mention that, thanks to Thompson, not only the prior marital status of Blake’s mother was discovered, but his mistaken hypothesis nevertheless led also to the location of the papers of the Muggletonian archive, going back three centuries, which was found in the possession of the last known Muggletonian, and is now available to scholars in the British Library.

Keri Davies has expended much energy on research investigating three important themes:

Firstly, to what extent was Blake influenced by his mother’s putative faith, which he now identifies as Moravian, rather than Muggletonian.

Secondly, related to that, to what extent could he be regarded as being radical in either faith or politics as, for example, E. P. Thompson portrayed him.

Thirdly, to what extent was Blake an ‘unknown painter’ as his first biographer Gilchrist christened him, or did he have a wider audience?

In this essay, I intend to concentrate on the first two of these themes.

Blakean scholarship has much reason to be grateful to Keri Davies, whose exhaustive archival research has modified and deepened our understanding of the object of its study. However, admiration and gratitude need not imply a lack of criticism, as we shall see. To begin with, Davies seems partly motivated by a peculiar animus against E. P. Thompson, whose reputation he seems to think unwarranted when one considers his ideological motivations and supposed sloppy scholarship, particularly in the archive.

Unexamined and Unverified Ideas

He describes Thompson’s work thus: “E.P. Thompson’s acclaimed Witness against the Beast is a recent example of unexamined and unverified ideas in Blake Studies.”6 This is echoed in Davies and Worrall: “E.P. Thompson’s posthumously published Witness Against the Beast… is an example… of the persistence of unexamined and unverified ideas about dissent and antinomianism in Blake studies.”7 We will come back to this later.

Notwithstanding that Thompson was wrong about Blake’s mother’s genealogy and religious background, Davies concedes that Thompson did make the ‘extraordinarily important discovery’ that mother Catherine was married twice.

Davies’ point of departure in his journey is his disquiet over the unusual name ‘Hermitage’, which Thompson foists upon the prior Catherine Wright before the occasion of her second marriage, to James Blake. Thompson can find no ‘Harmitages’ in Westminster Parish records, as we have seen, and jumps to a conclusion which favours his own hypothesis.

Davies argues – convincingly it seems to me – that ‘Harmitage’ was an affectation that cockneys sometimes adopt, aping their ‘betters’ by adding the aspirant to words that begin with a vowel; and Catherine and her husband were, on the occasion of their nuptials, ‘talking posh’ to emphasise their respectability to the priest and congregation. Thus, Davies argues, the entry of ‘Harmitage’ in the register is probably a clerical error.8

‘Armitage’ is itself uncommon as a surname in the London of the mid-eighteenth century, and thus the marriage of Catherine Wright (her birth name) and Thomas Armitage that occurred sometime between 1740 and 1750 (and was the only such union) must be that of Blake’s mother and her first husband. Neither were of London stock: Catherine (née Wright) was of a family from a Nottinghamshire village, and Thomas was from Royston in the West Riding (where Armitage was a common name, particularly in the Huddersfield region). It has been suggested that some of Blake’s seemingly odd rhymes (at least to metropolitan ears) may derive from his learning to speak while listening to his mother’s possibly provincially accented tongue.9

Examining the Moravian Links of the Blake Family

After Thomas’ death, Catherine met James Blake, and they were married in the Mayfair chapel (again) in October 1752. Davies speculates that Catherine may have opted for another Mayfair wedding to avoid paying back some £80 to her in-laws, as per the provisions of Thomas Armitage’s will, found by Davies.10 He goes on to suggest:

The evidence of an Anglican, though irregular, marriage ceremony and baptism at the parish church, but later family burials at Bunhill Fields, suggests that either the Blake family were members of the Church of England at the time of their marriage, and moved towards religious dissent during William’s childhood, or that they were dissenters of a very mild persuasion (maybe Moravian, maybe Methodist), who perhaps objected to individual Anglican clergy (a political stance) but had no overriding theological objection to Anglican rites and ceremonies.11

Much intellectual labour was expended in the first half of the twentieth century in attempting to show that William Blake came from an unorthodoxly religious family, usually Swedenborgian. This particular notion was thoroughly debunked by David Erdman in his monograph, ‘Blake's Early Swedenborgianism: A Twentieth-Century Legend’,12 although this has not prevented later authors from ‘discovering’ links to other groups, particularly Baptists.13 But nobody has been able to show any firm evidence for the Blake family’s links to any organised dissenting groups, and, apart from an acknowledged brief dalliance with Swedenborgianism at a conference, none for William and Catherine (his spouse), either.

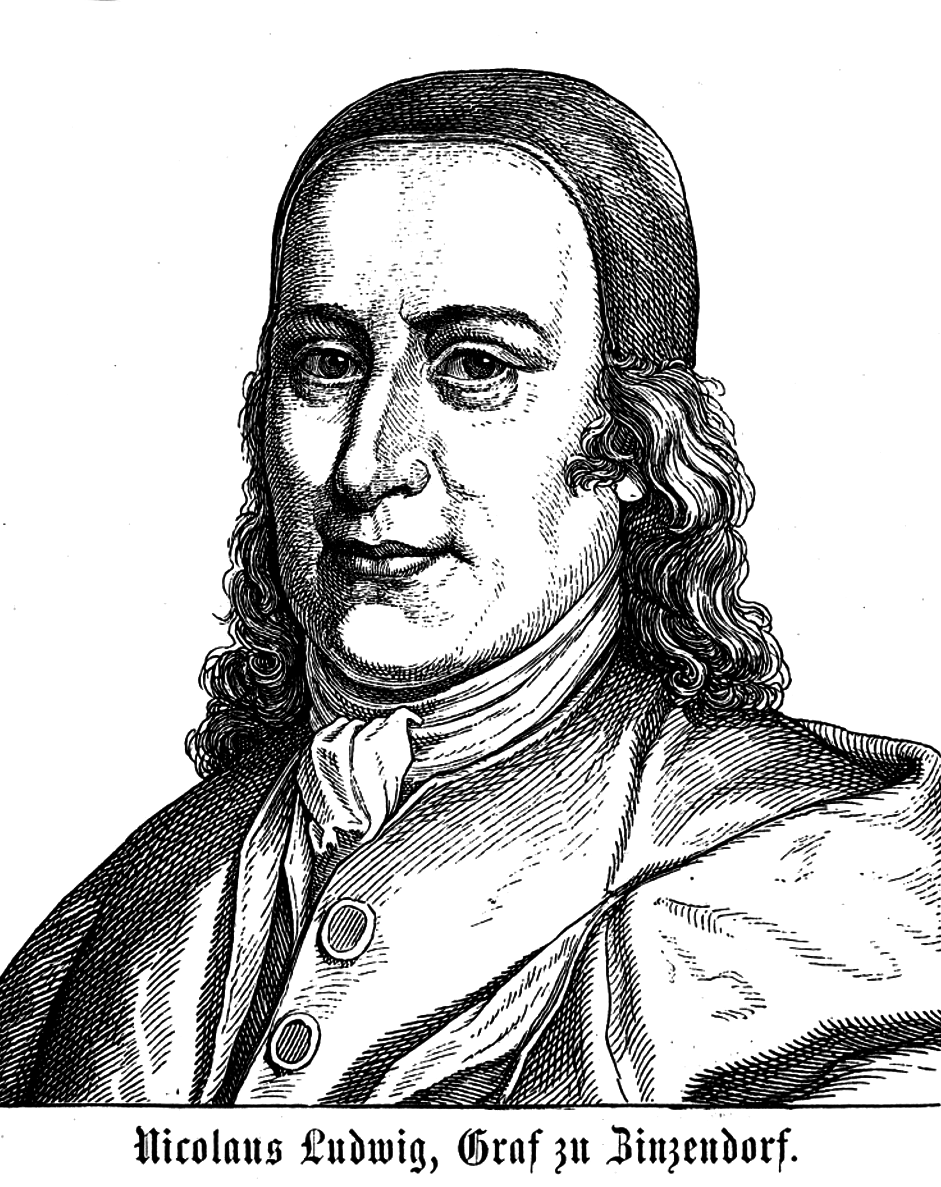

Davies has been very exercised in examining the Moravian links of the Blake family, in particular his mother; if not a Muggletonian either by ancestry or marriage, what could she be? Davies is not the first to think that she might have been Moravian, and that this affected William’s upbringing. In the 1920s, the biographer Thomas Wright, drawing on conversations he had with the Blake facsimilist William Muir, who got the story from family tradition (his great uncle had known Blake), put in his life of Blake that the artist’s family attended the Fetter Lane Moravian Chapel, and this was repeated in Margaret Lowery’s study.14 The theory was given new life by Nancy Bogen (1968), but it was Marsha Keith Schuchard who did the research that showed the connections. Davies has acknowledged her pioneering work and has built upon it, sometimes in collaboration with her in later essays.

Leaving the Congregation

In ‘Bridal Mysticism and “Sifting Time”: the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family’, Davies says that:

After their acceptance into the Congregation on 26ᵗʰ November 1750, Thomas and Catherine Armitage had only eleven months of membership before Thomas took the sacrament on his deathbed. He died (of ‘a slow consumption’), on 19ᵗʰ November 1751. The Fetter Lane Church Book records perfunctorily that Catherine “became a widow and left the congregation.”15

We have evidence that Catherine and Thomas Armitage (d.1751) were active members of the Moravian Church for just less than a year, but “[h]ow much, if any of the Moravian faith Blake's mother brought to her second marriage must for the time being remain a matter for speculation”.16 Davies suggests that leaving the congregation did not mean cutting all ties with the church, and that she likely kept attending meetings and services, but again, adduces no evidence for this.

Schuchard and Davies determined that there was one ‘Brother John Blake’ in the congregation at Fetter Lane, but, beyond the identity of a surname, there is no evidence that he was related to James Blake, future father to William. Davies does not say that he was, merely that it is ‘possible’. He goes on to suggest that upon Catherine’s bereavement, John (now promoted to ‘friend’ and not just another member of the congregation) might have introduced the young widow to his putative kinsman.

All this is, of course, ‘possible’, and if there were evidence to support it, it would be very interesting; but as there is none, it seems mere wishful thinking, serving to cement the Blake family more firmly within the walls of the Moravian edifice.17 In a later article, Davies describes John and his wife Mary as ‘probably William’s uncle and aunt’.18 There has been no further evidence to suggest this’; at least none is presented.

Davies gives us more of his evidence for Blake’s Moravian links in an article published in Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly.19 Here we find Blake bumping into an acquaintance in the Strand and having a brief conversation, during which Blake, typically and good-naturedly, pontificates to him about the reasons for practising art.

Davies argues, convincingly enough, that this is one Jonathan Spilsbury, a fellow engraver and a member of the Moravian sect.20 Davies argues that this casual meeting in a London street shows, contra Gilchrist, that Blake had a ‘wide social acquaintance’, which might well be right, but it doesn’t follow from this. He did become part of Hayley’s circle, but this did not necessarily make him close to Blake.

Otobah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano

Much of the article comprises a resume of the life of this man, which is of interest in itself, but most of which need not detain us here. In 1781, Jonathan and his wife Rebecca jointly requested admission to the Moravian community at Fetter Lane, but only Jonathan was accepted,21 and so Rebecca remained an Anglican, while Jonathan himself, having been turned down for ordination, had become a Moravian lay preacher.22

It should be noted that this is thirty years after Blake’s mother, Catherine, had left the congregation. Another possible link is that, while seeking work as a miniature painter, Jonathan sought advice from a Mr Cosway, who had been a teacher of Blake’s and remained his friend. While this is interesting and perhaps even suggestive, it still does not necessarily indicate anything closer than acquaintance between Blake and Spilsbury.23

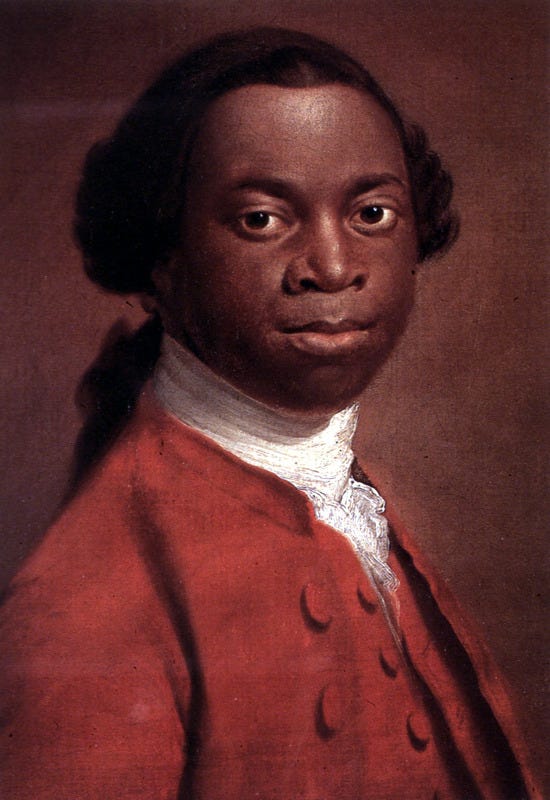

There is an interesting aside in the article concerning Spilsbury’s association with the Chapel of the African and Asian society. It is possible that Spilsbury may have met Otobah Cugoano (sometimes known as ‘John Stuart’), who was a leader of the London black abolitionists, along with Olaudah Equiano. Perhaps, Davies suggests, if Blake knew Spilsbury, this association might be one of the sources of Blake’s antislavery views.24

Giving Praise to God

It is the circumstances of Jonathan Spilsbury’s death in October 1812, or rather the manner of his passing, which is of particular interest to Davies. Rebecca had predeceased him in February and had been buried in Bunhill Fields (it was not that unusual for Anglicans to be buried there; it retained an Anglican priest, and one such may have conducted Blake’s funeral). Spilsbury died of the after-effects of a stroke on the 12ᵗʰ October 1812, and Davies quotes a long and moving account of his passing from the Moravian Church Diary for that time. He died, after praying for his soul and giving praise to God, surrounded by his friends and co-religionists, singing the Moravian hymn Praise God from Whom all Blessings Flow.

This is, by any account, a good death and one to which many may aspire. Davies compares it to Gilchrist’s account of Blake’s own demise:

On the day of his death,” writes Smith, who had his account from the widow, “he composed and uttered songs to his Maker, so sweetly to the ear of his Catherine, that when she stood to hear him, he, looking upon her most affectionately, said, ‘My beloved! they are not mine. No! they are not mine!’” … To the pious Songs followed, about six in the summer evening, a calm and painless withdrawal of breath; the exact moment almost unperceived by his wife, who sat by his side. A humble female neighbour, her only other companion, said afterwards: “I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel.”

And he goes on to give some more accounts of similar Moravian deaths marked and perhaps eased by song. This is intended to give more evidence to his contention that Blake was marked by his supposed early Moravianism for all of his life. A major difference between Blake and Spilsbury is that the latter sang Moravian hymns while Blake said that the verses he sang were given to him from beyond. Davies does give another example of this kind of otherworldly inspiration, being the account of the death of a Moravian woman, in Greenland: Mrs Drachart, the wife of a Danish missionary, but there is no suggestion Blake knew of her.25

The problem with all this is that the practice is not confined to Moravians in the nineteenth century. Many pious people of (mainly) Protestant dissenting groups have been known to follow it. A cursory search online will find many examples of present-day American Baptists bowing out while singing hymns of prayers. To go back to an example in Blake’s time: in 1812 the people (probably unjustly) convicted of being responsible for the violent acts of West Riding Luddism marched to the York scaffold singing the Methodist hymn, ‘Behold the Saviour of Mankind’.26 Singing as a way of preparation for death is not necessarily a mark of Moravian faith or sympathy with it.

Ambiguous Dissent and Conformity

We have suggested that in a variety of texts Davies illustrates Blake’s possible connections with the Moravian church without necessarily demonstrating that he was much influenced by it. We should examine the nature of this sect to which Blake had a familial connection. In 1749 the Acta Fratrum was passed, recognising the Moravians as an episcopal church in the Anglican tradition, and thus in alliance with the Church of England. Yet to function, their congregations had to be registered and licensed as dissenting chapels, putting them in an ambiguous position.

The Moravians were much admired by John Wesley from their arrival in Britain in 1738. They and Methodism became close both organisationally and in terms of their doctrine, which had initially greatly influenced the Wesleys. It seems unlikely though that their strict hierarchies and patriarchal system of elders would have appealed much to Blake, but their use of songs rather than theology as a preferred proselytising device, perhaps relayed through his mother, may well have played a part in influencing his poetry, especially up to and including the Songs,27 although Ripley suggests an influence going far beyond the 1790s.28

Magnus Ankarsjö is far more certain of the fact that “Blake was not raised a Muggletonian – he was a Moravian.”29 He gives little evidence for this, other than noting some congruences in language between the poet / artist / engraver’s work and the sect. One of these is the repeated use by Blake of the word and concept ‘lamb’. Davies had also taken this up.

The Lamb

He asserts that: “[t]here are striking resemblances of both theme and vocabulary between Blake’s poem ‘The Lamb’.” (I quote lines 13–16):

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb:

He is meek & he is mild,

He became a little child:I a child & thou a lamb,

We are called by his name.30

and Moravian hymns such as Hymn XXIII, ‘Hail, O Jesu, Sweet and Mild’, in the 1741 Collection, of which I cite here the final stanza:

Hail, my Jesus, sweet and mild;

Hail thou holy humble Child;

Thou didst give thy self for me,

Lo! I give my self to Thee.’31

The ‘striking resemblances’ here are the three words: ‘mild’, ‘child’ and ‘lamb’, none of which are particularly owned by either Blake or Moravianism. The lines in each example are heptasyllables, which is not unusual in English verse, particularly for children (cf: ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’). Nor is the theme exclusively Blakean, or indeed Moravian, but is a prominent leitmotif in almost all streams of Christianity.

The idea of Jesus as ‘the lamb of god’ comes from the gospel of John, which constructed Jesus as the sacrificial lamb of Passover, even changing the date of the crucifixion (it is a day earlier than the other three gospels) to make this a better fit. But whoever wrote this gospel knew his Torah; The Old Testament abounds with sacrificial lambs, going back to the beast that God sent down to obviate the death of Isaac. There is nothing particularly Moravian about this identification, despite all of Ankarsjö’s excitement when he comes across it in Blake’s poetry.32

We should not discount the fact that there is a Wesleyan hymn for children, which begins “gentle Jesus, meek and mild”, and note that the Wesleys had an early association with the Moravian sect before leaving over disquiet about certain of its sexual practices and doctrine.33 Blake probably would have heard this hymn and may have been – consciously or otherwise – influenced when writing ‘The Lamb’, but this proves nothing about his beliefs. I have heard it many times and am not a Moravian or Methodist. As an aside, Davies’ bête noire, Edward Thompson, was raised a Methodist (as was Christopher Hill), and it could be maintained that his fiery prose and argumentative style derive from this early influence. Nobody, however, would seriously suggest that this means he retained this Methodism in later life.

Wayne Ripley (2017) provides quite a lot of evidence for the influence of the Moravian hymnal upon Blake’s poetry from the Four Zoas onwards, including the use of the word Zoa itself, which appears in the text. It does not necessarily show, and Ripley does not directly suggest that it does, that Blake was a Moravian at that date.

Blake was syncretic by nature, he took things from many traditions and mythologies. For instance, the name ‘Vala’ is the name of the prophetess and guardian of nature in the Elder Edda, the main source for Norse mythology. The fact that he may have appropriated some Moravian symbols, and even words and phrases, from their hymn books should not be taken at face value.

If Catherine had this book, and we should note that it was published after she left the congregation, it is possible that Blake took some of his imagery from it, and Ripley shows some convincing data. It is also possible that Blake either acquired or saw it in adulthood, as was the case with much of his exposure to religious and other literature.

The Antinomian Controversy

The notion that Blake was in any way antinomian has become controversial in recent years, with Keri Davies and David Worrall in a jointly written text suggesting that the term, at least as used by E. P. Thompson is meaningless, as Thompson defines antinomians as those who will be redeemed by faith alone, rather than works. They argue that this definition suggests that almost all Christians – or all Protestants, at least – are antinomians, including any communicating members of the Church of England,34 and it is, of course, the teaching of Paul.35 Davies here insists that antinomianism is often confused with ‘anti-legalism’ (the ideas that the Mosaic law has been superseded, see below), but does not realise that this is only one part of the antinomian belief system.

Before we go on here, it must be pointed out that Thompson did not say that Blake’s only influence was a putative antinomian tradition. In a review of Jon Mee’s Dangerous Enthusiasm: William Blake and the Culture of Radicalism in the 1790s, Thompson notes that the ‘alchemical philosophers’ must be recognised as an influence alongside antinomianism. And apropos that, Thompson states that, in Mee’s study:

Kathleen Raine’s The Great Tradition goes unmentioned, and while one may dispute her theme and many of her inferences (as I do) her work and that of related scholars cannot simply disappear without explanation.36

What Davies and Worrall say about Thompson’s definition is true, as far as it goes, but David Como and David Hall both point out that antinomianism (which originated as a term of abuse), while not a coherent and organised faction, could be characterised by certain further tendencies. Firstly, those so categorised were hostile to overt demonstrations of piety, which they saw as self-serving and hypocritical.

The second of the tendencies was ‘anti-legalism,’ i.e. their acceptance of the doctrine of free grace meant that the Moral Law of Moses, including the Ten Commandments, was irrelevant to them. This usually wasn’t a rejection of ‘morality’ per se, but of what were seen as the hypocritical practices of puritan divinity, and they used the rhetoric of puritanism to attack puritanism itself. It was Christ’s sacrifice that “fulfilled and abolished, once and for all, the Law of Moses.”

The righteous were thus not only free from the Law, but from sin itself, at least in the eyes of God.37 Yet freedom from sin did not mean that they were free to sin. This distinction remained true for almost all antinomian texts up until the early Stuart period, although things could be different in the febrile atmosphere of the Revolution and Interregnum.38 During this period, the more radical of believers went further in that they believed that as God was contained within their being, and thus they were without sin, and so the Ten Commandments, and Mosaic Law in general, the ‘Moral Law,’ did not apply to them at all, in thought or deed.

lay me down among the swine

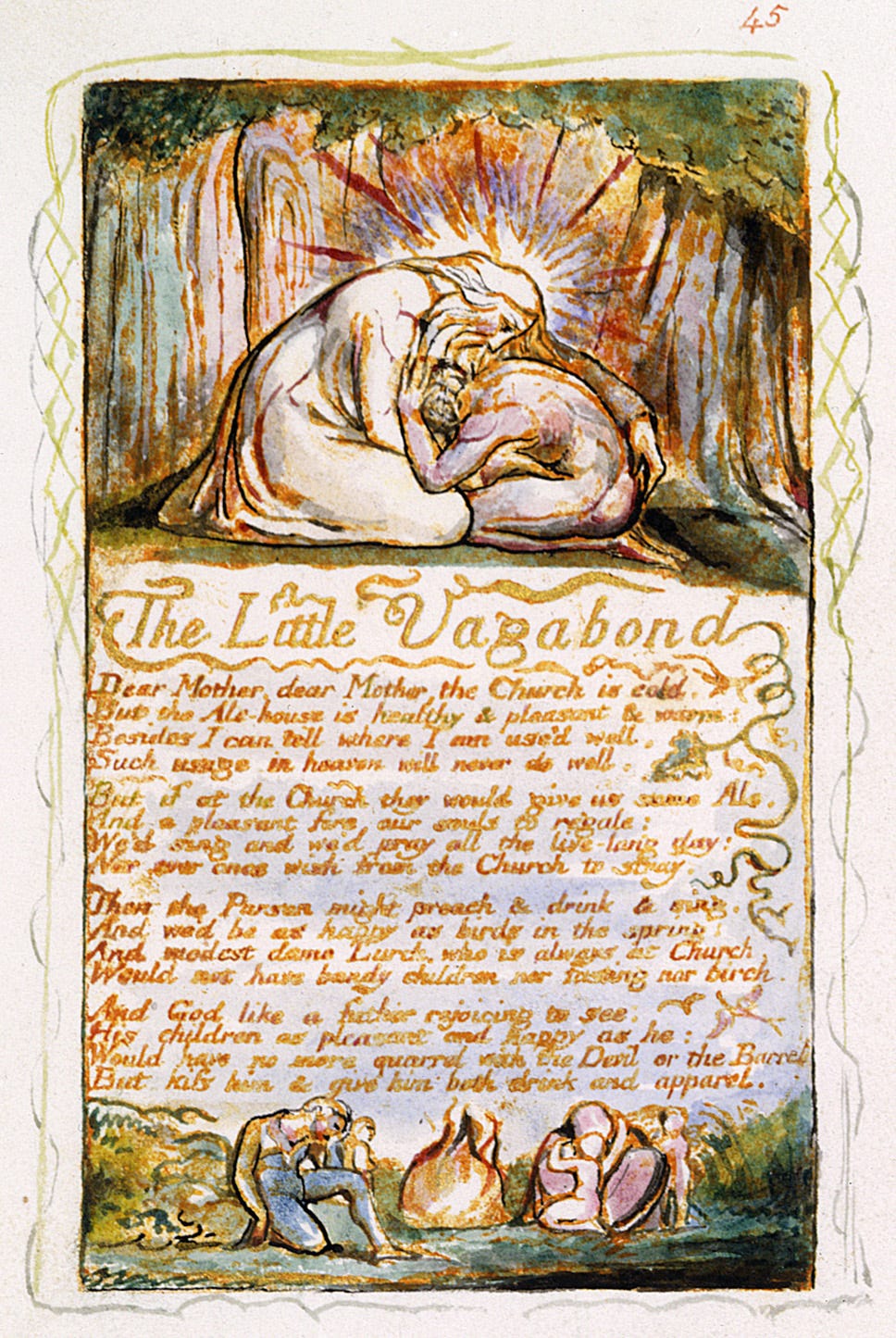

They also believed that any physical church or organised ministry was unnecessary and may be, indeed, a form of blasphemy. Abiezah Coppe writes the following on the title page of ‘A Fiery Flying Roll’: “With a terrible word, and fatal blow from the Lord, upon the gathered CHURCHES.”39 In this context, we may well examine such of the Songs of Experience as ‘The Garden of Love’ and ‘The Little Vagabond’, where a similar hostility is shown, if more mildly expressed. The reported phenomena of cold and unwelcoming churches and repressive ‘priests in black gowns’ are instructive.40

I Saw a Chapel All of Gold

Any mildness is certainly absent in the poem from the notebooks that begins: “I saw a chapel all of gold…”, which is filled with hatred and disgust of such buildings and the hypocrisy within, which excluded any true believers who “weeping stood without.” As the serpent lay upon the altar “…vomiting his poison out / On the bread and on the wine,” the poet in disgust turns from these trappings of hypocritical orthodoxy and, finding a sty, “lay me down among the swine”.41 The last image was probably a sideswipe against the conservative commentator and philosopher, Edmund Burke, who characterised the common people as “the swinish multitude.” This is dissent from the official church and from the politics of reaction linked; indeed, religion is politics, as Blake wrote in Jerusalem.

The avowed preference of the ale-house to the church in ‘The Little Vagabond’, may be a reference to the fact that Dissenters often used private rooms in inns and beer houses for their meetings to avoid prosecution under the Conventicle Acts of 1664 and 1670, whereby people were fined escalating amounts for attending religious meetings in buildings other than the state churches.42

Davies’ and Worrall’s idea of the nebulous nature of antinomianism has a corollary, which is the notion that Blake’s religion was, at heart, ‘orthodox’. This belief dates at least back to J.G. Davies,43 but has a vigorous life still.44 The problem with this approach is that ‘orthodoxy’ itself has to be defined so widely, in an attempt to accommodate such texts as The Everlasting Gospel,45 as to be rendered almost useless as a category of analysis.

Little that he said or did in between those services shows him to have much sympathy with the established church, or any other organised sect

An ‘orthodoxy’ that expresses hostility to the Old Testament idea of God and casts doubt upon the virgin birth and physical resurrection is a strange creature indeed. Ryan argues that, for instance, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, where the best arguments are given to the devils of Hell, this is just Blake’s dialectical method and does not bear on his religious views.46

What does ‘orthodoxy’ even mean here? Blake was indeed baptised into the church of England, and married in it, and his funeral service was conducted according to the Anglican rituals, so his life was punctuated by the trappings of the national church. It is also reported by his friend, John Thomas Smith, that Blake never attended any form of public worship from 1788 until his death.47 In the end, Blake also asked to be buried in the dissenters’ graveyard at Bunhill Fields, where Catherine Blake joined him a few years later. Little that he said or did in between those services shows him to have much sympathy with the established church, or any other organised sect.

Davies and Schuchard (2004) say that, “It’s as if Catherine, his own wife, did not know where his preferences lay,” when she had to ask him where he would like to be buried, and which minister he would prefer to conduct the service. They go on to reference Nancy Bogen, who suggested that the Blake family were Anglicans, but who never let go of their Moravian roots (Moravians being encouraged to join Anglican congregations, as mentioned above). There are several problems with this.

The first is Blake's attitude to state religion, which he referred to as “The Abomination that maketh desolate… The Source of all Cruelty.”48 The second is Smith’s statement about Blake’s lack of attendance at divine services, as quoted above. It is true that we only have Smith’s word for this, but do we have any reason to doubt him? It conforms to what the historian and biblical scholar, Bart Ehrman, calls “the criterion of contextual credibility”, i.e. it is congruent with many other things that we know about Blake’s attitude to organised religion from his writings.49

Thirdly, their interpretation of Catherine’s lack of knowledge as to William’s preferences is open to question. Is it not as likely, or even more likely than his spouse’s ignorance as to his religious preferences, that Catherine knew very well that her husband was critical of and unenthusiastic about both alternatives, and thus asked him for guidance? Perhaps, just as he chose Bunhill Row because his family was buried there, he chose the Anglican service because he had been baptised and married according to those rites (although he had no choice as to the first, and the second was in an informal chapel). To him, it was all one, it was what happened afterwards that was significant in his eyes. It is also possible that he knew and disliked the dissenting minister, and his choice was therefore personal rather than theological.

How unlike the father!

William Blake (of Jesus)

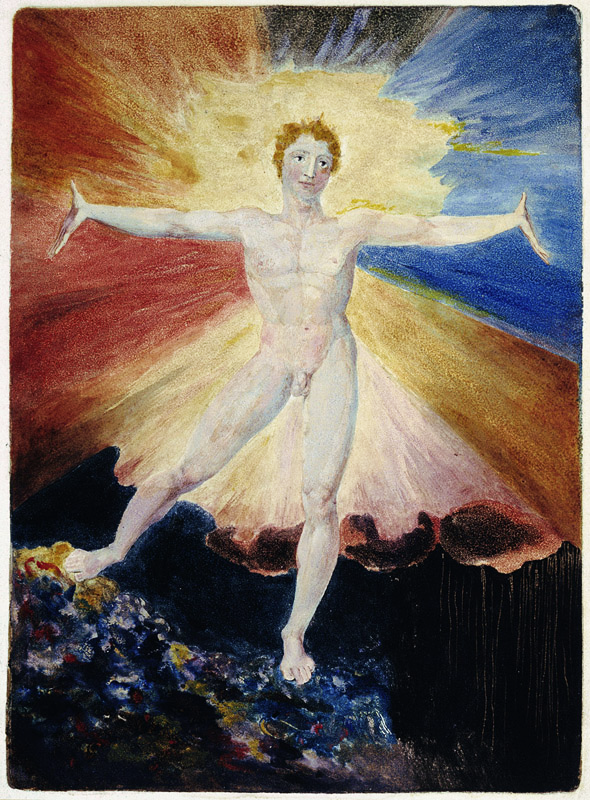

Blake was a fiercely independent and original religious thinker, which seems to preclude him from any lasting sympathy with organisational orthodoxy. When he railed, as he did on many occasions, against the vengeful God of the Old Testament and declared of Jesus, “how unlike the father”,50 he seems to take on the clothes of the persecuted sect of Marcionites, who believed that the God of the Old Testament was a different being to that of the New.51 When he invented the satanic demiurge Urizen, who believes he is God the creator and constructs metal books full of rules to bind humanity under “One King, One God, One Law”,52 he dresses as a Gnostic. In his terminology of ‘emanations’ for various of his great spirits, he is likewise following Gnostic terminology.53 Christian orthodoxy was constructed against these tendencies, among many others, and armoured by the iron laws of churches and states against any such assaults from without. Blake was neither Marcionite nor Gnostic, but neither was he anything remotely ‘orthodox’ (in contemporary usage).

Blake acknowledged the influences of Boehme and Swedenborg readily. If his upbringing was so suffused with Moravianism as Ankarsjö, Davies, Ripley, Schuchard, etc., say and also suggest that it went on throughout his life in some cases, is it not strange that he never explicitly referred to it?

The Tyger, Tamed

We now come to Davies’ animus against the historian E. P. Thompson. Thompson believed that Blake was a radical both in religion and politics, and this has drawn further ire from Keri Davies. As far as Thompson’s views on religious dissent goes, Dr Davies has this to say:

One can only label Blake a ‘dissenter’ if, like Thompson, one uses a definition of dissent so broad as to be meaningless. Donald Davie, for example, in his Church, Chapel, and the Unitarian Conspiracy has challenged E. P. Thompson’s merging of religious and political dissent.54

Keri Davies has a penchant for considering Thompson’s definitions meaningless. As to challenging the latter, Donald Davie certainly did that, but he was scarcely a disinterested commentator, being very conservative in both politics and religion. Of course, he is no more to be criticised for that than Thompson is for his (rather recondite and unorthodox) Marxism. He and Thompson had crossed swords on more than one occasion, but not without some mutual respect among the disagreements. For instance, in this review by Thompson in 1980 of Davie’s collection of lectures, A Gathered Church:55

Professor Davie is striking out at a number of lazy notions and received opinions as to Dissent. In particular, he is contesting the notion that the major dissenting tradition can be seen as an easy evolution towards liberal, humanist, or even rationalist conclusions; or, indeed, the notion (for which he holds Christopher Hill and myself responsible) that Dissent can be claimed, wholesale, as part of the pre-history of the Left. Such notions, as he properly shows, can be profoundly condescending if they pass by or disallow the authenticity of the Dissenters' spiritual and doctrinal concerns. Moreover, the Socinian 'enlightenment' cannot be taken as representative of Dissent as a whole; there were Tory Dissenters as well as Jacobins, and the former may have remained within their gathered churches more loyally than the latter. These points are often well made; and they should be taken… [but]… Professor Davie is claiming his 'genealogy' as the true Dissent, and disallowing all other parts of the tradition. As I have argued, this is preposterous, limiting, and often enforced by dubious rhetorical strategies.56

As can be seen, this is combative, but appreciative and (to some degree) even-handed. It shows that Thompson’s notion of Dissent is far more nuanced than the caricature espoused by Keri Davies, and certainly much less dogmatic than he would allow.

Donald Davie sees himself at odds with Thompson and ‘the left’ over whether Dissent espouses individualism or collectivism, but does not deny that there is a tension between the two that he does not know how to resolve.57 However, Davie does commend Thompson for some things: for instance, for his assessment of the Socinians, saying “…that excellent writer, our Marxist historian E. P. Thompson, has written that they ‘pushed God so far back into his Baconian heaven of first causes that he became, except for purposes of moral incantation, quite ineffectual.’”58

Davies is much exercised by the description ‘anti-Court candidate’

Elsewhere, Davie says that Marxist historians “deserve the gratitude… of anyone who aspires to the ideal of disinterested enquiry…” for taking note of what he considers to be the unjustly neglected Methodists. And E. P. Thompson in particular has “earned our gratitude on these grounds.”59 Of course, he profoundly disagrees with their conclusions, but disagreement need not embrace contempt nor dismissal. He thinks Thompson’s definitions of both ‘old’ and ‘new’ dissent wrong, and he might even throw the word ‘preposterous’ back at him, but he would never have been so trite as to call them ‘meaningless’.

While arguing that Blake’s family were not ‘radical dissenters’ but ‘mild’ Moravians, Davies is also concerned by the claim that Blake and the Blake family had anything to do with radical or popular politics. In Witness Against The Beast, Thompson had examined the poll books of the 1749 Westminster election and discovered that what he thought were Catherine’s then current and her future husband both voting for the ‘anti-Court’ candidate.

In fact, Hermitage was a misidentification, but the ‘clerical error’ ‘Harmitage’ and James Blake, who was to become William’s father, alike voted in the way Thompson described.60 Davies is much exercised by the description “anti-Court candidate”, seemingly seeing it as a dishonest circumlocution to conceal the fact that Blake’s father voted for a Tory, and concluding, triumphantly: “Thus we must ‘finally abandon’ the ‘lazy cliché’ that Blake’s family were radical in both religion and politics.”61

However, if we examine the context of Thompson’s statement, in the by-election of 1749, we find that Westminster was a ‘scot and lot’ borough, which means that it had a relatively mass popular franchise – i.e. all the male ratepayers had a vote. And, according to the historian of eighteenth-century politics, Nicholas Rogers:

In contrast to the City of London, a political community with a long-standing tradition of independence of Crown and government, Westminster politics were conducted under the shadow of the Court.62

and this marked and affected the political allegiances in the borough. Furthermore, elections in the borough were not conducted in a particularly calm and orderly manner, even by the loose standards of the time. As Rogers says: “The 1749 election turned out to be one of the most violent and vituperative struggles of the first half-century”.63 To express a preference for any party but the ‘Court’ party could be perilous. Thus, James Blake was courageous in voting the way that he did.

There was more than one reason for this electoral disorder, but one of the main ones is that Britain had been recently troubled by a Jacobite rebellion, which failed at least partly because of the pusillanimous nature of Charles Edward Stuart’s allies, the Scottish clan leaders, who lost their nerve and forced a disastrous retreat. If the insurgent army had reached London, it may well have found it with an apathetic populace who were most unwilling to defend it, as had been the case with Manchester.64 But whatever the truth of that, the tiny and unrepresentative electorates of England had mainly returned Whigs in the general election of 1747, as the Tories were associated with Jacobitism and insurrection. This voting elite was also much concerned with the loyalty of the common folk for, as one commentator said at the time, ‘The eyes of people are much opened by rebellion’ (Rogers 1973: 76).

Thus, the Whigs, who had run an ossified and corrupt one-party state for the previous quarter of a century, were de facto the ‘Court Party’. The ‘Independents’, the small traders, shopkeepers, etc., who made up a sizeable portion of the electorate of Westminster, undoubtedly saw the unrepresentative Whigs as their social enemy and largely, but not exclusively, supported the Tory candidate – the representative of the ‘anti-Court party’.

The Whigs were definitely not the ‘left-wing’ party and the Tories were not unproblematically and monolithically ‘right-wing’

When James Blake, a hosier, voted Tory in 1749, (as indeed did Catherine’s first husband, Thomas Armitage) he was voting for the anti-Court Party, as Thompson rightly said. We do not know if James Blake could be considered a political radical or not, but it is clear that any radical in this election would have voted for the Tory candidate, and that doing so was very unlikely to be an act of satisfaction with the status quo, as that was expressed by the rule of the Whig oligarchs. “It would be wrong to dismiss the anti-ministerialism of the towns as the result of residual sectarianism or Tory grandeeship.”65 In such places, the ‘reactionary’ thing to do would be to vote for the Whigs.

To bolster his claims of the lack of any oppositional enthusiasm behind the voting behaviour of Blake’s father, Davies claims that Rogers denies the existence of any class feeling among the artisan and shopkeeper voters of Westminster and states that the voting patterns in the 1749 election were ‘incoherent’.66 In fact, what Rogers says is: “…it is difficult to make a rigid equation between trade and Independency and the genteel character of the Court vote.”67 The key word here is ‘rigid’.

In fact, according to Rogers’ research, 75-80% of the monied and landed interests voted for the Whig, while of the votes for the Tory, the ‘anti-Court’ candidate, 90% were ‘Independents’, like James Blake. Of course, the largest proportion of the Whig vote also consisted of ‘Independent’ voters, otherwise the Whigs could never have won in Westminster, but the class split was still striking.68 It is not a clear class cleavage, but of course it never is: politics, even the politics of class, is not that simple. As well as social and economic factors, cultural and ideological ones come into play, which always muddy the pool.

Oppositional politics can take place under many odd banners

Davies quotes Monod to the effect that as the opposition to the Whigs may have been at least partly motivated by Jacobite sympathies, it could not possibly be counted as radical.69 This ignores the fact that oppositional politics can take place under many odd banners, and there are many examples of this in history: the Pilgrimage of Grace, the left-wing Carlist faction in twentieth-century Spain, to name but two. Most uprisings have some kind of social dimension, and any enthusiasm for the Jacobites in the 1740s was likely as much fuelled by a dissatisfaction with the status quo as for the desire to see another Stuart enthroned.70 And, as O’Gorman points out, the Jacobitism of the Tories was of “a nebulous sort”.71

It is yet another calumny against Thompson to suggest that he deliberately attempts to mask the supposed non-radical politics of James Blake by hiding his Tory sympathies under the cloak of ‘anti-Court’ antagonism. It is characteristic of Keri Davies’ mode of argument, where this particular dead historian is concerned, that he does not give any evidence to suggest that James Blake was not a radical, other than the fact that he voted ‘Tory’ in a very specific set of circumstances.

We should be reminded that we cannot simply map late twentieth-century politics onto those of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Whigs were definitely not the ‘left-wing’ party and the Tories were not unproblematically and monolithically ‘right-wing’ (those labels did not yet exist and awaited a revolution elsewhere). Both parties were coalitions of interests and ideologies, which often shifted and re-sorted under specific political conditions. Thompson, as a historian of the politics of those times, knew that.

It was not until after the 1832 Reform Act that the modern party system even began to take shape

To further explicate the point, let us take two examples of prominent politicians from Blake’s prime of life: Edmund Burke and William Pitt the Younger. These two were respectively the ideological underpinner and the political doer of the repressive decade of the 1790s. They were both Whigs. From the early nineteenth century, we may take the examples of the ‘radicals’ William Cobbett and Richard Oastler. They both started off as Tories; but it was not a Toryism recognisably akin to that of our age.

It was not until after the 1832 Reform Act that the modern party system even began to take shape, and it was not until in the wake of two further Reform Acts that it took on the form something like that which was recognisable for most of the twentieth century (although there was another partial re-sorting post 1918). It possibly looks like breaking down again at the moment, which is a reminder that nothing is fixed in history. To get back to our point and make it plain: Blake’s father did vote for the ‘anti-court candidate’, and in saying that he did so, Thompson masks nothing.

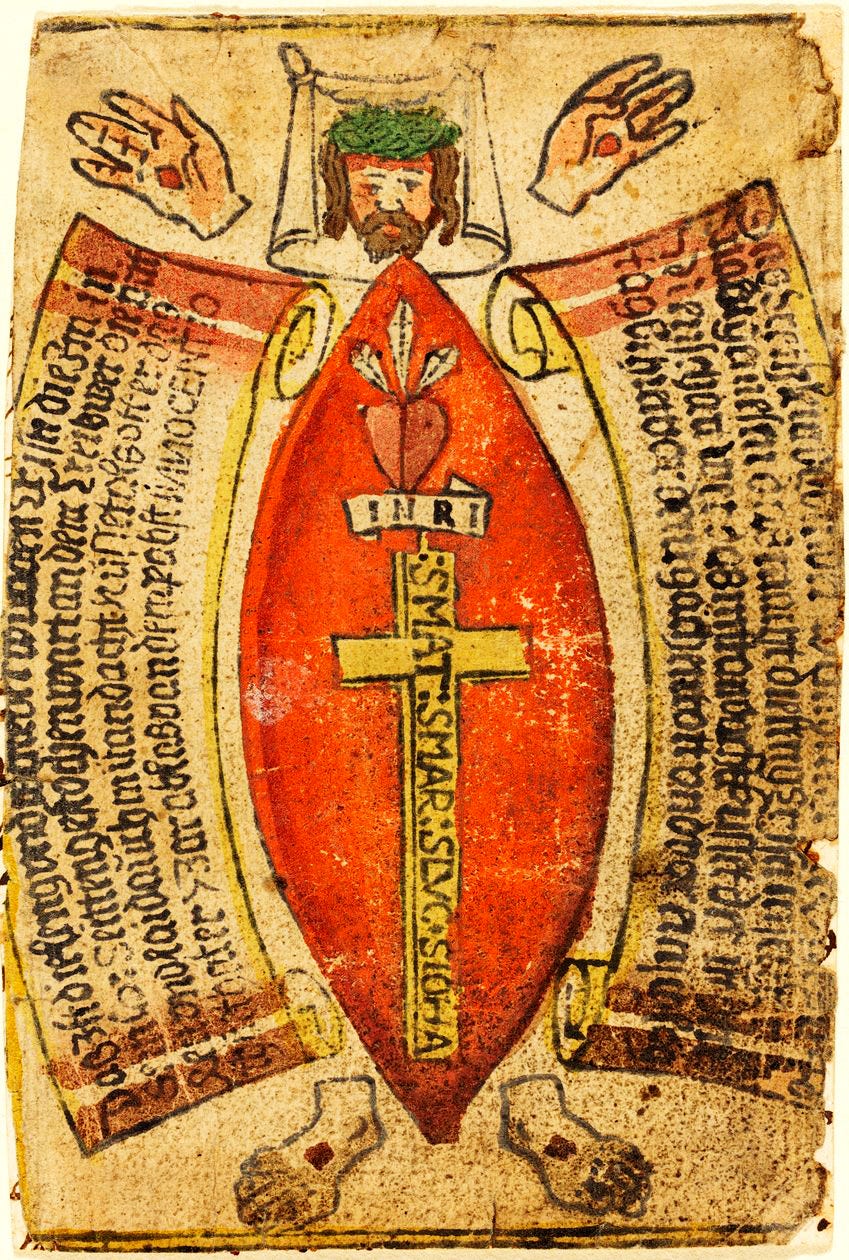

Sexual Healing vs. Mild Dissent

Before we finish, we should briefly examine to what extent the Moravians were ‘mild’ dissenters at the time of Catherine’s affiliation? Or were they, to use a term with which Schuchard labels them, ‘antinomian’?72 If they were, it was of quite an authoritarian bent. Although sex within marriage was seen as a sacrament, and Christ’s wounds (particularly the wound in his side) were sexualised and compared metaphorically to various female parts (breast, womb etc), the Moravian Church at Fetter Lane, as was the case abroad, divided its adherents into gender and age specific ‘choirs’, in order to reduce temptation.73 They did offer a form of ‘marriage guidance’, as Davies describes, and he conjures a scene from The Four Zoas to suggest that Blake’s work was influenced by this, but marriage itself was tightly controlled and the ‘elders’ seem to have practiced a kind of social eugenics, in which people of particular statuses, trades and professions were matched up.74

But it was their attitude to sex that set them apart from the mainstream and the non-enthusiasm of Anglicanism to which Davies would like to associate them. Davies informs us that:

[b]ecause Christ had a sexual organ and was born into the world through the female organ, sexual organs and the sexual act could not be regarded as sinful or shameful; such matters should be talked about naturally, rather than treated as taboo.75

This seems to most people who live in the modern world a most healthy attitude. It was not the normal outlook of mainstream eighteenth-century Christianity, however.

Enthusiasts and Sodomites

Whether or not Blake had any association with them (and we have noted that he would probably have found their patriarchal authoritarianism uncongenial), certain aspects of their worship might well have appealed to him. They saw Christianity as something to be celebrated joyously, in a playful, often child-like manner. But it could also have very ‘adult’ aspects. This was the ‘sifting time’, and:

[t]he Moravian development in this direction was to reach its climax in… the 1740s, when exuberance tipped over into excess…76

Certainly, in Europe, and especially in Germany (although perhaps also in London), this ‘excess’ was to become sexual before it was eventually suppressed by the church hierarchy. According to Atwood: “[t]he Sifting is used in Moravian historiography to describe a time of fanatical excess within the Moravian Church.”77 They were also suspected of homosexual practices by some influential public figures. Indeed, during the debate on the Acta Fratrum in 1747 Robert Nugent, the Whig MP for St Mawes in Cornwall, described the Moravians as “Enthusiasts and Sodomites”, and declared that he wanted nothing to do with them.78

Podmore comments that “England was not the centre of Sifting Time spiritually, but there is no suggestion that it was immune from it.”79 Podmore goes on to comment that it is not coincidental that this was precisely the time when the Moravian Church underwent a massive expansion in England.80 That is, just at the time when it looked less like an adjunct of the state church and more like an antinomian sect. There seems nothing ‘mild’ about ‘Sifting Time’.

Attempting to Eliminate Unfavourable Aspects of History

The Moravian hierarchy was very keen to try and hide this particular time in their history by a deliberate winnowing and destruction of their archives. As Peucker tells us:

…they attempted to eliminate what they considered as unfavorable aspects of their history. After Zinzendorf’s death in 1760, the leaders of the Moravian Church successfully reinvented the church as a noncontroversial denomination with clear Lutheran-Pietist leanings but without any of the former elements of radical Pietism or enthusiasm. This new image of the Moravians was not only promoted in print, the archives itself was to reflect this image as well.81

This is the time Catherine Armitage (later Blake) had her membership. Davies posits that she might have left because of the suppression of the ‘Sifting Time spirituality’ that she found attractive.82 It is equally possible, I suppose, that she left because the Sifting Time emphasis on sex had discomfited her, as it had Wesley. Unless there is the unlikely event of the discovery of a written testimony by Catherine or one of her confidantes, we will never know. What we can say is that any talk of William Blake having a ‘Moravian upbringing’, as Ankarsjö and Erle put it, is an unsubstantiated conjecture.

All we can reasonably say is that the infant William was brought up by a mother who had been, briefly, a member of a Moravian group

Almost all of the titles of Keri Davies’ published articles contain some variant of the formulation ‘the lost Moravian history of William Blake’s family’. This ‘lost history’ seems, when it comes down to it, to consist of the discovery that William Blake’s mother was, for a relatively short time, before he was born, a member of a Moravian congregation. All else is speculation.

All we can reasonably say is that the infant William was brought up by a mother who had been, briefly, a member of a Moravian group. She may have enthusiastically passed on some of their core precepts to him; or she may have wanted to put it all behind her, or the truth may lie somewhere in between. What we do know is that there is no evidence anywhere that is not circumstantial or inferential that her most gifted child ever identified as a Moravian. He certainly left no testimony to that effect.

Notum Pictorem

It would be wrong to close without mentioning some of the other discoveries Keri Davies has made. He seems to have convincingly shown that Blake, at least early in his career, did have some kind of audience, although for work that was completely his own, it was not very large. But, to do some violence to Gilchrist’s Latin, as a Pictor Blake was not quite as Ignotus as we have assumed.83

Also, there has always been a slight puzzlement about how a not very well off, even in the best of times, artisan could have got so well read and erudite about not only English literature, but, beyond that, the classics and European esoterica. Davies suggests, quite convincingly, that Blake might have had access to the extensive libraries of some of his patrons. Some of these collections were sold off after their owners’ demise, and so Davies was able to determine much of their content through auction catalogues.84

It is very unlikely that Blake was either a Muggletonian or a Moravian, but he was a voracious reader, and Davies has perhaps gone some way to explain how he was able to feed that desire to gain knowledge.

This essay has focused entirely upon Keri Davies’ attempts to deny Blake any connection with ‘radical’ religion or politics, casting him as a ‘mild’, almost-Anglican, possible-Moravian. I have tried to show that we have much cause to doubt some of the inferences that he takes from the evidence he has so admirably amassed. I have also questioned some of his assumptions about antinomianism and eighteenth-century politics. The main problem is that he has amassed this evidence with a great degree of labour, but then has made many assumptions and conjectures that he then goes on to treat as virtually factual.

A Radical in Every Thought and Word

Some of his conclusions may well be correct, but we would need much more evidence to say for certain. The main contribution he has made is that concerning Blake’s mother and her one-time religious affiliations, but on that is built a most shaky edifice of Blake’s relationship with Moravianism. Because he sees Moravianism as ‘mild’ dissent at most (which is itself open to question, certainly at the time that Catherine Armitage / Blake was associated with it – even Schuchard refers to it as ‘antinomian’ during the ‘Sifting Time’) – Blake must be a ‘mild’ dissenter at most.

Davies regards any association of Blake with ‘antinomianism’ or ‘radical’ dissent as ‘outmoded’ scholarship, which seems only to mean that he disagrees with it. And to cap it all off, on dubious grounds, he labels James Blake a Tory (while disregarding the complexities of this label in the mid-eighteenth-century) and thus by a sleight of hand disqualifies his son from having radical political views.

If we look at Blake’s own pronouncements on the matter, we find no direct mention of Moravianism. Certainly, Ankarsjo and Ripley in particular suggest certain possible influences evidenced by some congruence of phrasing in even his later works, which might tell us that he had read Moravian texts, as he had many others. But it could also be mere coincidence, as much of the same phraseology and imagery can be found in the bible.

Blake, in his conversations with Crabbe Robinson, does not mention the sect and, even worse for Davies’ thesis, goes on to state his disbelief in the omnipotence of God and says that Jesus makes mistakes. He sounds like a Ranter when he says that “What are called vices in the natural world are the highest sublimities in the spiritual world”, repeating things said in Marriage three decades previously.85 He often expressed in various works his hostility to any organised religion and explicitly preferred his own ‘system’. Blake was not a Muggletonian, not a Moravian, but a radical in his every thought and word.

'I must Create a System, or be enslav'd by another Man’s

William Blake

Brian Collier

Bradford, Apr 2025

Bibliography

Ankarsjö, Magnus (2009) William Blake and Religion: A New Critical View (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland and Company).

Atwood, Craig D. (1997) ‘Sleeping in the Arms of Christ: Sanctifying Sexuality in the Eighteenth-Century Moravian Church.’ Journal of the History of Sexuality Vol. 8, No. 1.

Beer, John (1968) Blake’s Humanism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1968).

Como, David R., Blown by the Spirit: Puritanism and the Emergence of an Antinomian Underground in Pre-Civil War England (Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, 2004).

Bentley, G.E. Jr (1969) Blake Records (Oxford at the Clarendon Press).

Bentley, G.E. Jr (2001) The Stranger from Paradise: a Biography of William Blake (London, Yale University Press).

Bentley, G. E. Jr (2010) ‘Blake's Pronunciation’, Studies in Philology Vol. 107, No. 1.

Bogen, Nancy (1968) ‘The Problem of William Blake's Early Religion’, The Personalist Vol. 49, Issue 4.

Crabbe Robinson, Henry (ed. Edith J. Morley) (1922) Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Lamb, etc.: Being Selections from the Remains (Manchester University Press).

Davie, Donald (1995) Essays in Dissent: Church, Chapel and the Socinian Conspiracy (Manchester, Carcanet).

Davies, J. G., (1966) The Theology of William Blake (Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books).

Davies, Keri (1999) ‘Mrs Bliss: A Blake Collector of 1794’, in Steven Clark and David Worrall (eds.) Blake in the Nineties (Basingstoke, MacMillan).

Davies, Keri, (2003) William Blake in Contexts: Family, Friendships, and Some Intellectual Microcultures of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century England (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Surrey).

Davies, Keri (2006) ‘The Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family: Snapshots from the Archive’, Literature Compass 3/6.

Davies, Keri (2006-7) ‘Jonathan Spilsbury and the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family’, Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, Vol. 40, Issue 3.

Davies, Keri (2009) review of Rix (2007), BARS Bulletin 34.

Davies Keri (2012) ‘Bridal Mysticism and ‘Sifting Time’: The Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s family.’ In Bruder, Helen P. and Connolly, Tristanne J. (eds) Blake, Gender & Culture (London, Routledge).

Davies, Keri and Schuchard, Marsha Keith (2004) ‘Recovering the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family.’ Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, Vo. 38, Issue 1.

Davies, Keri and Worrall, David (2012)., ‘Inconvenient Truths: Re-historicizing the Politics of Dissent and Antinomianism’, in M. Crosby, T. Patenaude, and A. Whitehead (eds). Re-Envisioning Blake (London, Palgrave).

Ehrman, Bart D. (1999) Jesus, Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millenium, (New York: Oxford University Press).

Ehrman, Bart D. (2003) Lost Christianities: The Battle for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew (New York, Oxford University Press,).

Erdman, David V. (1953), ‘Blake's Early Swedenborgianism: A Twentieth-Century Legend,’ Comparative Literature Vol. 5, No. 3.

Erle, Sibylle (2024), ‘Divine Humanity; or, God Appears When We Appear Godly’, Vala, Journal of the Blake Society, Issue 5.

Foster, S. Damon (2013), A Blake Dictionary (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press).

Gilchrist, Alexander, The Life of William Blake (London: Bodley Head, 1906).

Hall, David D. (2019), The Puritans: A Transatlantic History (Princeton and Oxford, Princeton University Press).

Hill, Christopher (1978), ‘From Lollards to Levellers’, in: Maurice Cornforth (ed), Rebels and their Causes : Essays in Honour of A.L. Morton. (London: Lawrence and Wishart).

McLynn, Frank (2012), The Road Not Taken: How Britain Narrowly Missed a Revolution 1381-1926 (London, The Bodley Head).

Mee, Jon (1994), ‘The Radical Enthusiasm of Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.”’ Journal of Eighteenth Century Studies 14.

Mee, Jon (1994a), Dangerous Enthusiasm: William Blake and the Culture of Radicalism in the 1790s (Oxford University Press).

Mee, Jon (1994b), ‘Is There an Antinomian in the House? William Blake and the After-Life of a Heresy’, in Historicizing Blake, ed. Steven Clark and David Worrall (Basingstoke: Macmillan), pp3-58.

Monod, Paul Kléber (1989), Jacobitism and the English People 1688-1788 (Cambridge University Press).

Mullet, Charles F. (1937), ‘The Legal Position of English Protestant Dissenters, 1689-1767’ Virginia Law Review Vol. 23, No. 4.

O’Gorman, Frank (1997), The Long Eighteenth Century: British Political and Social History 1688-1832 (London, Arnold).

Paley, Morton D. (2005), ‘Review of “Blake Records,” by G. E. Bentley’, Studies in Romanticism Vol. 44, No. 4.

Peucker, Paul (2006), ‘”Inspired by Flames of Love": Homosexuality, Mysticism, and Moravian Brothers around 1750’, Journal of the History of Sexuality Vol. 15, No. 1.

Peucker, Paul (2012) ‘Selection and Destruction in Moravian Archives Between 1760 and 1810’, Journal of Moravian History Vol. 12, No. 2.

Podmore, Colin (1998), The Moravian Church in England, 1728-1760 (Oxford, The Clarendon Press).

Ripley, Wayne C. (2017), ‘The Influence of the Moravian Collection of Hymns on William Blake’s Later Mythology’, Huntington Library Quarterly Vol. 80, No. 3.

Rix, Robert (2007), William Blake and the Cultures of Radical Christianity (Abingdon, Ashgate Publishing),

Rogers, Nicholas (1973) ‘Aristocratic Clientage, Trade and Independency: Popular Politics in Pre-Radical Westminster’, Past & Present 61.

Rogers, Nicholas (1984) ‘The Urban Opposition to Whig Oligarchy, 1720-60’ in James & Margaret Jacob (eds), The Origins of Anglo-American Radicalism (London, Allen & Unwin).

Rudé, George (1971), Hanoverian London (London, Secker and Warburg).

Ryan, Robert (1997), The Romantic Reformation: Religious Politics in English Literature, 1789 -1824 (Cambridge University Press).

Schuchard, Marsha Keith (2006) Why Mrs Blake Cried: William Blake and the Sexual Basis of Spiritual Vision (London, Century).

Thompson, E. P. (1968), The Making of the English Working Class (Harmondsworth, Penguin).

Thompson E. P. (1980), ‘Review of “A Gathered Church: The Literature of the English Dissenting Interest, 1700-1930 by Donald Davie”’. The Modern Language Review Vol. 75, No. 1.

Thompson, E. P. (1993a), Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law (Cambridge University Press).

Thompson, E. P. (1993b) “Blake’s Tone,” (a review of Mee 1994a, London Review of Books Vol. 15 No. 2).

Thompson, E. P. (1997), Beyond the Frontier: The Politics of a Failed Mission: Bulgaria 1944 (Woodbridge, The Merlin Press).

Peter Titlestad (2004) ‘William Blake: The Ranters and the Marxists’, English Academy Review 21:1.

Hill 1978:49.

Thompson 1993:90.

Thompson 1993:120-1.

Thompson 1993:95.

Thompson 1993:120-1.

Davies and Schuchard 2004:37.

Davies and Worrall 2012: 35.

Davies 2003:41.

Bentley 2010.

Davies 2003:49, 54.

Davies 2003:56-7.

Erdman 1953.

Bentley 2001:7-11.

Both cited in Schuchard, 2006: 8ff.

Davies 2012:64.

Paley 2005:640.

Davies 2006:1311.

Davies 2012:59.

Davies, 2006-7.

Davies 2006-7:101.

Davies 2006-7:107.

Davies 2006-7:106.

Davies 2006-7:106.

Davies 2006-7:107.

Davies 2006-7:108.

Thompson 1968:639-40.

Davies and Schuchard 2004:38; Rix 2007:10.

Ripley: 2017.

Ankarsjö 2009:8.

William Blake, ‘The Lamb’, Songs of Innocence and of Experience, in David Erdman, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, New York: Random House, 1988 (1965), pp8–9 (from here on, references to Erdman are given as, eg., E8-9).

Davies 2006:129.

See in particular Ankarsjö pp54ff. where every occurrence of the word ‘lamb’ in Blake’s work is seen as evidence of Moravianism

Davies 2012:60.

Davies and Worrall 2012:44 ff.

KJV Epistle to Galatians, 1:4-9, 5: 4

Thompson 1993b.

Como 34-5.

Como 36.

See also Mee 1994a:60.

William Blake, Songs, E26: 44 & 45.

William Blake, ‘I Saw a Chapel All of Gold’, E467-8.

See Mullett 1937.

Davies, 1948.

See, e.g. chapter 2, ‘Blake’s Orthodoxy’ in Ryan, 1997.

William Blake, The Everlasting Gospel, E-518.

Ryan 1997:54ff.

Bentley 1969:258.

William Blake, ‘Annotations to an Apology for the Bible’, E-618.

Ehrman 1999:94-5.

William Blake, ‘Annotations, E-565.

Ehrman 2003:104-8.

William Blake, The Book of Urizen, E-72.

Ehrman 2003:123.

Davies 2006:1315.

Reprinted in Davie, 1995

Thompson 1980:168.

Davie 1995:230-1.

Davie 1995:127.

Davie 1995:132.

Thompson 1993:121.

Davies 2006: 1316

Rogers 1973:71.

Rogers 1973:77.

Mclynn 2012:313.

Rogers 1984:134.

Davies 2003:51.

Rogers 1973:93.

Rogers, 1973:80-1, 93-4.

Davies 1989:229-231.

See McLynn 2012:331 ff.

O’Gorman 1997:150.

Schuchard 2006:48.

Atwood 1997:26ff.

Atwood 1997: 43-4.

Davies 2012:60.

Podmore 1998:17.

Atwood 1997:27 n.6.

Podmore 1998:257; see also Peucker 2006.

Podmore 1998:132.

Podmore 1998:136.

Peucker 2012:195. It seems that the Moravian hierarchs, like the British state, were keen to employ what E. P. Thompson describes as ‘weeders’ and ‘anti-historians’ (Thompson 1997:20.)

Davies 2012:69.

See, for instance, Davies 1999.

See, for instance, Davies 2003

Crabbe Robinson 1922:3-9.

Andy, every time I read you I learn so much.