“In the spring of 1960, when Tony Cliff and Michael Kidron with a small group of us started the first series of International Socialism, it had a subtitle, ‘Journal of Socialist Theory’. By implication, what passed for socialist theory – after the ravages of Stalinism and the successive dilutions of social democracy – was quite inadequate for an understanding of the modern world, let alone for undertaking action that connected aims and strategy. Without constant reconnection between aims and a rapidly changing world, theory easily became a set of quasi-religious mantras, esoteric marks of group identity rather than guides to action – and the history of Trotskyist sects is sadly replete with too many examples.”

Nigel Harris, All Praise War!

Summary

Revolutionary Left's Rise 1945-1985 Overview

John and Andy discuss the rise of the revolutionary left from 1945 to 1985. They start by examining the situation at the end of World War II, including the positions of Social Democrats and the Communist Party. They cover the emergence of the New Left from its post-war origins through significant developments in the 1960s. The discussion will provide context on key groups and figures, touching on the influence of the Russian Revolution. They explain how leftist movements expanded beyond a small niche during this 40-year period.

Russian Revolution's Impact on Leftist Groups

The discussion focuses on the historical context and impact of the Russian Revolution, particularly its influence on the revolutionary left in the post-World War II era. John explains the appeal of Bolshevism and its role in shaping the political landscape of Europe, emphasizing how it became a powerful myth that attracted various political forces. Andy adds that this ‘structure of feeling’ around the Russian Revolution is crucial for understanding the collective career of the revolutionary left in the post-war years, as it became a central point of reference for different leftist groups, including Trotskyists and the Communist Party, even when they disagreed with each other.

Trotsky's Post-War Predictions and Their Impact

John and Andy discuss the aftermath of World War II and its impact on various political movements. They focus on how Trotsky's predictions about post-war events were largely incorrect, leading to a crisis among Trotskyists. The Labour Party in Britain implemented significant social reforms, which was unexpected and challenging for far-left groups to explain. The Communist Party, despite some growth, suffered ideological setbacks, while mainstream reformist forces gained strength. The discussion highlights the difficulties faced by Trotskyists in adapting their theories to the new realities of the post-war world, including the expansion of the Soviet Empire and the absence of a capitalist crisis or revolutionary wave.

1950s Leftist Thought and 1956

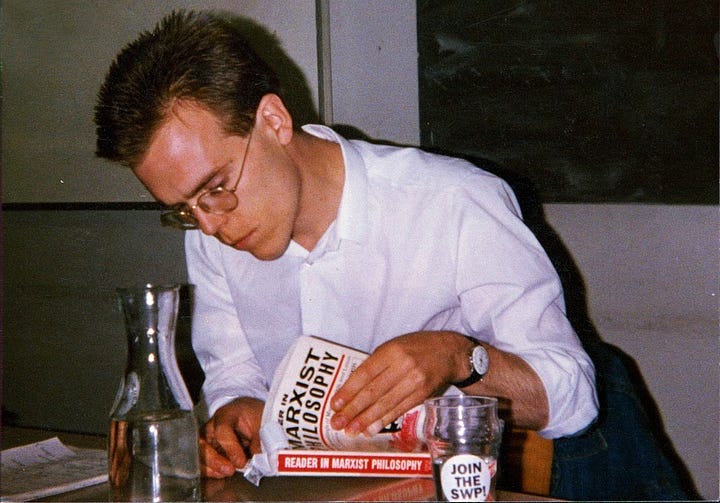

John and Andy discuss the development of leftist thought in the 1950s, highlighting three key factors: new forms of worker struggle, the impact of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, and anti-colonial movements. They emphasize the significance of 1956 as a turning point for the revolutionary left, particularly in how it led to a reevaluation of Trotskyist perspectives on the Soviet Union. Andy introduces Tony Cliff's State Capitalist analysis of Russia as a fundamental break from Trotskyism, leading to new ways of understanding international relations. John adds context about the intellectual climate of the time, discussing the concept of ‘anti-anti-communism’ and how certain leftist positions, such as neutrality in the Korean War, were considered extremely controversial.

Post-War Britain's Working-Class Militancy

The discussion covers the social and economic changes in post-war Britain, focusing on the rise of working-class militancy and confidence from the 1950s to the 1970s. John and Andy highlight the impact of consumer society, technological advancements, and cultural shifts on working-class consciousness and activism. They note the paradoxical effect of these changes, which both diluted and strengthened working-class identity. The conversation then moves to the decline of this militancy in the late 1970s and early 1980s, culminating in the miners' strike of 1984-85. They describe this strike as a turning point and the last major struggle of the traditional workers' movement, marking the end of an era in British labor history.

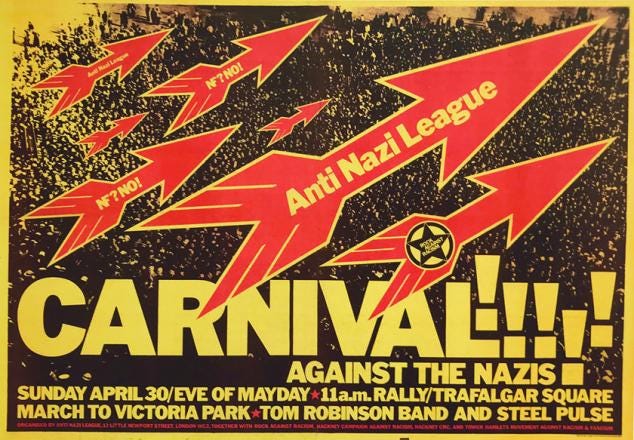

Far Left in Britain's Evolution

The discussion covers the history and evolution of the far left in Britain from the 1950s through the 1980s. John provides a generational overview, highlighting key periods like the 1950s rebuilding of socialist traditions, the rise of CND in the early 1960s, the impact of 1968 and student movements, the workplace focus of the 1970s, and the miners' strike of the 1980s. He emphasizes how each period shaped leftist thought and activism, noting both achievements and challenges. The conversation touches on the transformative impact of events like the miners' strike on participants and the broader left, as well as the eventual decline and loss that followed. John and Andy reflect on the complexities of analyzing this history and the difficulties in reconciling past beliefs with current understanding.

… the first and, up to now, the only total revolution against total bureaucratic capitalism, [a system that in] its purest, most extreme form has been realized in Russia, China, and the other countries presently masquerading as socialist.

Cornelius Castoriadis, on the Hungarian uprising, 1956.

Tony Judt: Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945

“Khrushchev’s secret speech, once it leaked out in the West, had marked the end of a certain Communist faith. But it also allowed for the possibility of post-Stalinist reform and renewal...

But the desperate street fighting in Budapest dispelled any illusions about this new, ‘reformed’ Soviet model. Once again, Communist authority had been unambiguously revealed to rest on nothing more than the barrel of a tank. The rest was dialectics.

Western Communist parties started to haemorrhage… In Italy, as in France, Britain and elsewhere, it was younger, educated Party members who left in droves. Like non-Communist intellectuals of the Left, they had been attracted both to the promise of post-Stalin reforms in the USSR and to the Hungarian revolution itself...

For forty years the Western Left had looked to Russia, forgiving and even admiring Bolshevik violence as the price of revolutionary self-confidence and the march of History. Moscow was the flattering mirror of their political illusions. In November 1956, the mirror shattered...

Shorn of the curious magnetism of Stalinist terror, and revealed in Budapest in all its armored mediocrity, Soviet Communism lost its charm for most Western sympathizers and admirers...

The difference in Eastern Europe… was that the disillusioned subjects of a discredited regime could hardly turn their faces to distant lands, or rekindle their revolutionary faith in the glow of far-off peasant revolts. They were perforce obliged to live in and with the Communist regimes whose promises they no longer believed… Their expectations of Communism, briefly renewed with the promise of de-Stalinization, were extinguished; but so were their hopes of Western succour…

For most people living under Communism, the ‘Socialist’ system had lost whatever radical, forward-looking, utopian promise once attached to it, and which had been part of its appeal... It was now just a way of life to be endured. That did not mean it could not last a very long time… in many ways, 1956 represented the defeat and collapse of the revolutionary myth so successfully cultivated by Lenin and his heirs.”

Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945.

Buy me a Coffee / Subscribe

Read On

Trump's Triumph and its Heralds: Think Like a White Man

It is an easy thing to talk of patience to the afflicted

Phil Smith's Eco-Eerie & Occupy's Haunted Generation

Phil Smith, Albion’s Eco-Eerie: TV and Movies of the Haunted Generation, Shrewsbury: Temporal Boundary Press, 2024.

Share this post