The Brilliant New Hercules: Blake for Artists Talk, 14 Oct 2024

Andy Wilson will be talking about his book, The Brilliant New Hercules: A Blake Reader, for the Blake for Artists group. Free to join. Details below.

Andy Wilson, The Brilliant New Hercules: A Blake Reader

talk to the Blake for Artists group

8pm Monday 14th October 2024

free to attend

Slide Deck

see the entire slide deck here »

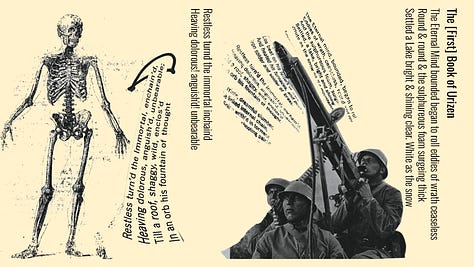

The Brilliant New Hercules

The Brilliant New Hercules was created in a fit, a month-long spasm of the mind, when I was first engaging with Blake’s work. I don’t consider myself an artist, although I am of course actually an artist, as are we all. We just need to make things in an untrammelled way. Certainly, though, I am not a professional artist. I am not a professional anything.

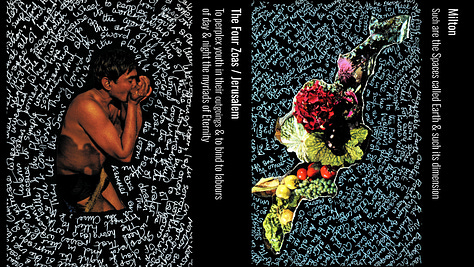

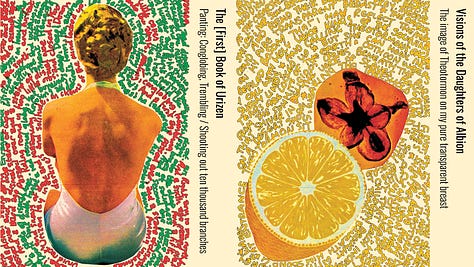

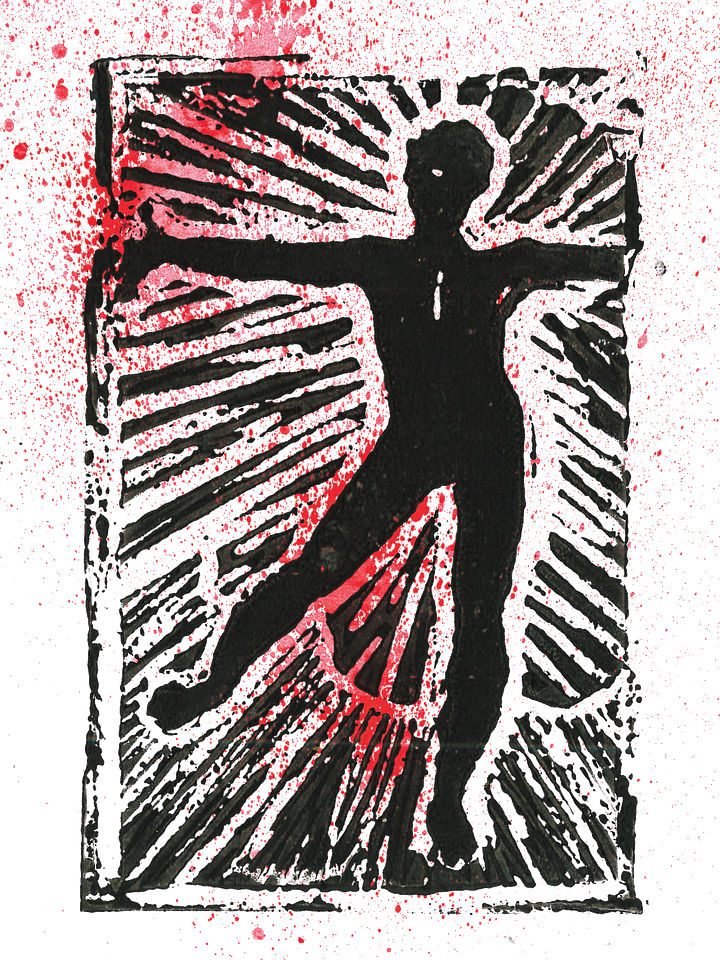

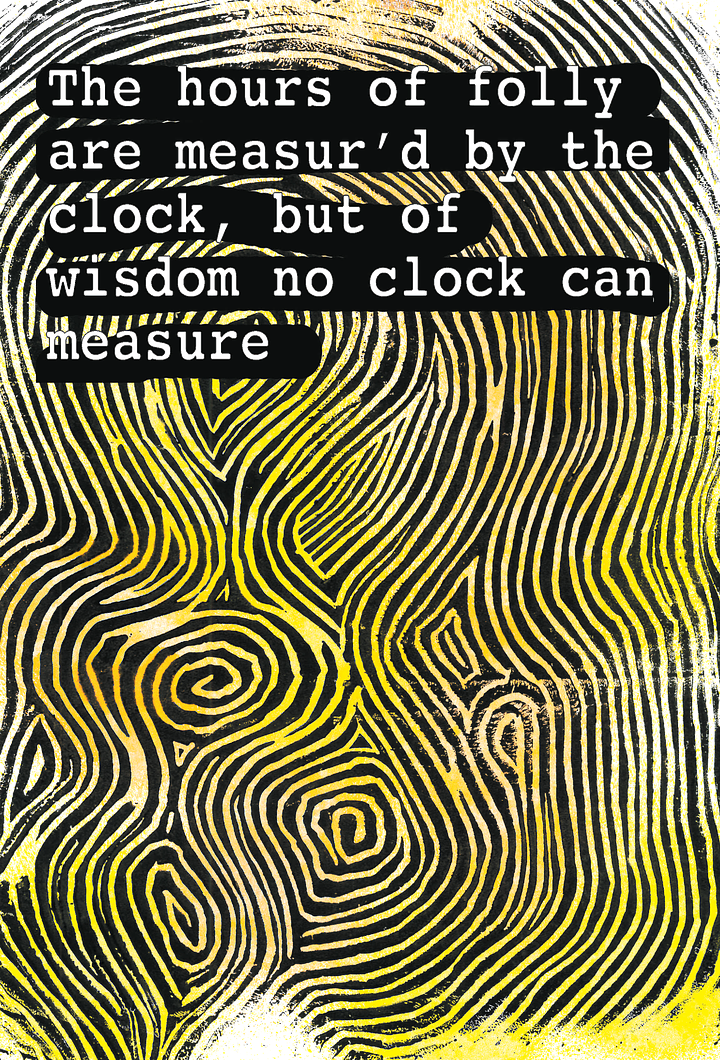

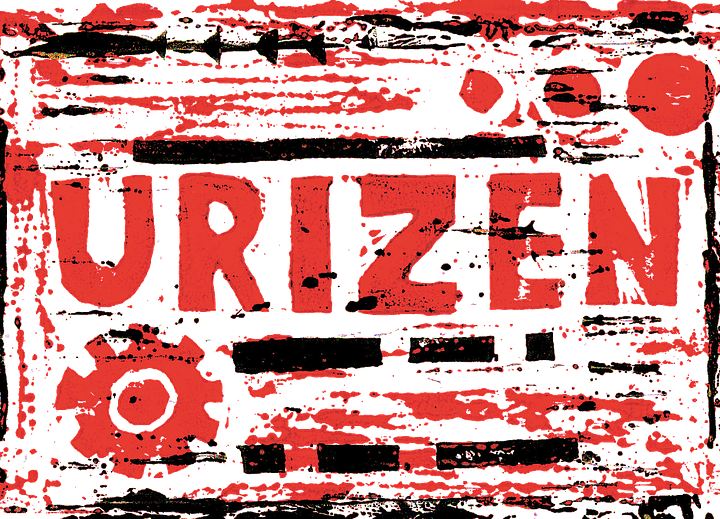

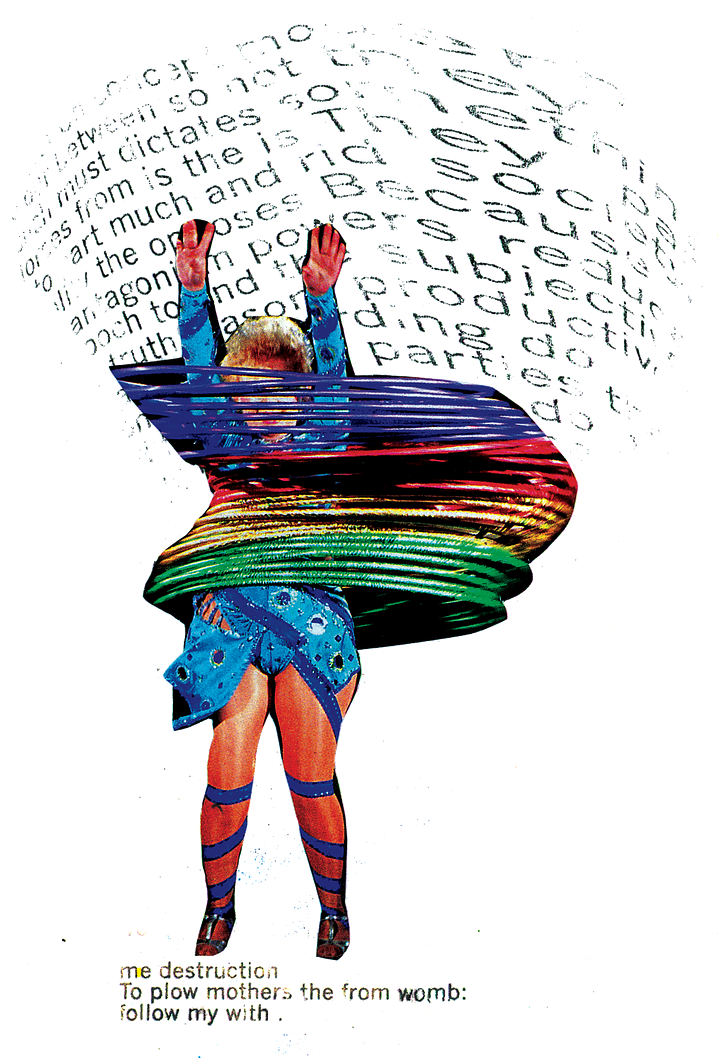

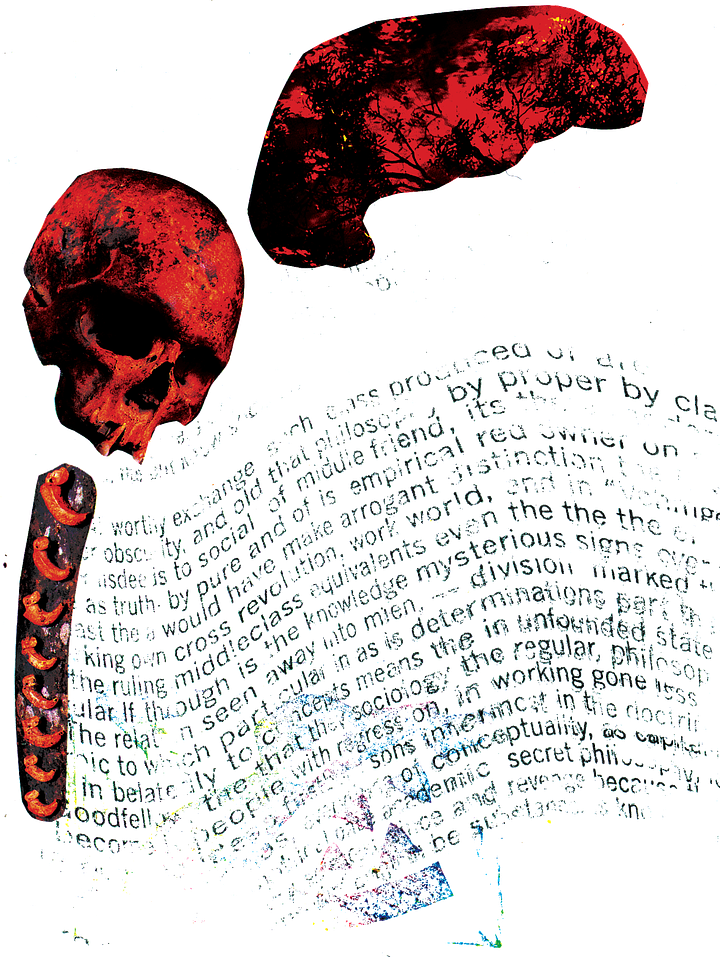

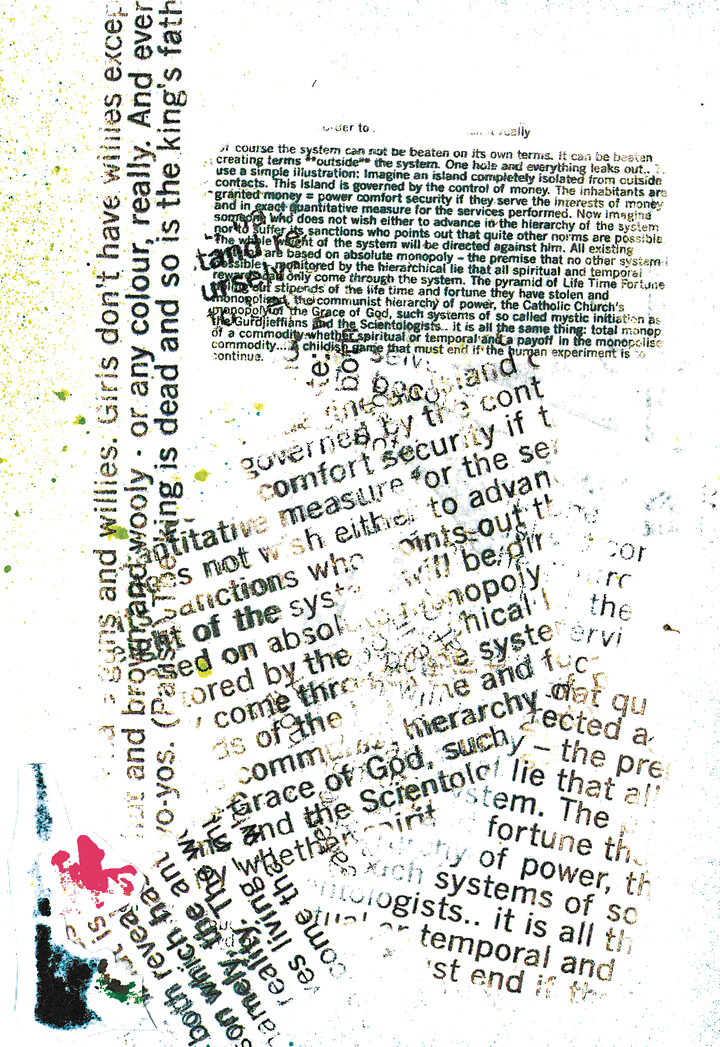

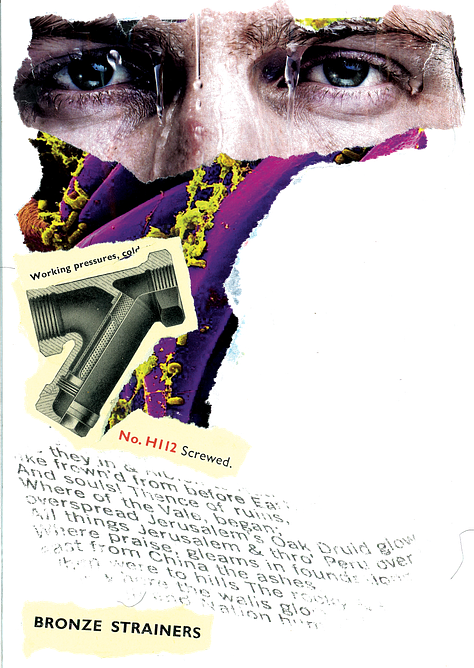

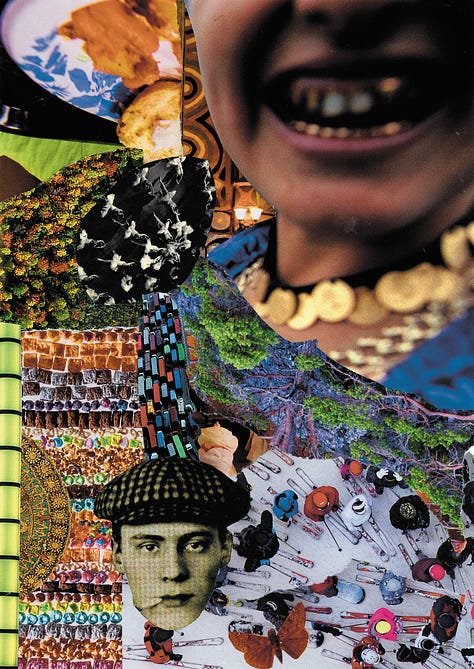

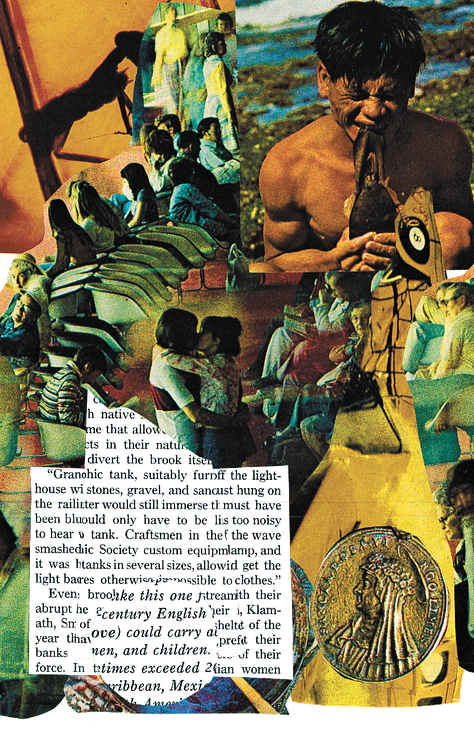

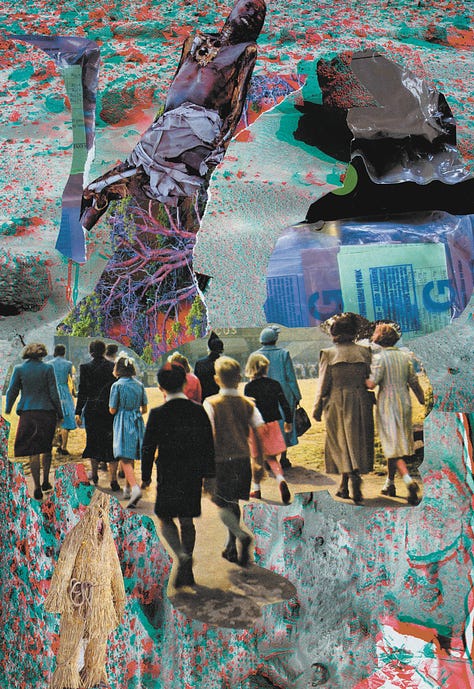

Images and texts for the book were created spontaneously using a number of approaches, and the results fed back on themselves so that, eg., a lino-cut image might then be processed on the computer, or cut up as part of a collage. I tried to introduce dislocations into the results and make new connections, using cut-ups and free association.

Blake resists his works’ implication in the production of readers as reproductive receptacles, possibly repeating what they are told, by splitting his texts into an assemblage of textual and visual parts with varying significatory interests.

Julia Wright

I wanted people to stop reading Blake as if the poems were simple hymns, the recitation of which works a magic charm. Instead, Blake is made to confound before he can enlighten. Hopefully, this leads us to see Blake as if from the corner of the eye, less focussed, but letting us see past what was seen before into what was previously hidden, or unexpressed, so we recognise Blake still but he looks different, new.

What I aimed at above all was to make Blake unsafe, to make him easier to understand in his true sense by making him harder to read the usual way. We have got used to ‘Toby-Jug Blake’ - an irascible, loveable old cockney nationalist and mystic, who spoke in parables to children and sang like a choirboy. But, as the Surrealists understood, Blake’s methods and concerns are just as often thrillingly modern in their indirections and their complexity. Blake uses a raft of alienation techniques to make sure his work cannot be read literally, as if it were programmatic or a manifesto (yes, even his manifesto, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell).

Such redirective, alienation methods used by Blake include polyvocality (conflicting voices appear as equals), perspectivism (each of those voices may be coherent in its own terms), and the over- and under-determination of meaning by providing too much, or too little, information. Blake sometimes seems to throw sand in his own face, at least if you believe his aim was transparency. Often these effects are achieved through the contrasts between the words on the page and the accompanying images (‘who are you going to believe - me, or your own, stupid lying eyes?’) The result is the creation of polysemia (“having multiple meanings”), achieved through the absorption of chaos and disorder into the work as a valid aspect of its creation.1

By further developing his own, unique printing processes, Blake leapt over the division of labour in his time between writer and illustrator. These were two distinct roles in the production of a book. But many others could have done what Blake did, if they had recognised the problem. His innovations did not involve cutting-edge science or engineering, just a hugely inventive mind. In the same way, digital publishing today allows an author to do whatever they want on the page… and yet everyone proceeds as before, ignoring the potential that exists to subvert the usual distinctions and narrow specialisation. So I wanted to make a book in which word and image got off with one another as they danced.

The title of the book was taken from an advert in an old engineering magazine for a lump hammer, the Hercules, announcing ‘the brilliant new Hercules!’, which put me in mind of Blake’s powerful, terse and laconic early works made at home while living in the Hercules Buildings, Lambeth (For Children: The Gates of Paradise, for example).

Art is not a mirror held up to reality

but a hammer with which to shape it.

Bertolt Brecht

I wanted to achieve a (colour) xeroxed, punk-fanzine sheen to things, so the saturation on images was turned up to ten. Sadly, the printing process dialled that back automatically to a six or seven, meaning the images look better to me in a digital file. I turned the saturation up all the way to eleven for digital images going online. The whole world turned day-glo.

Techniques

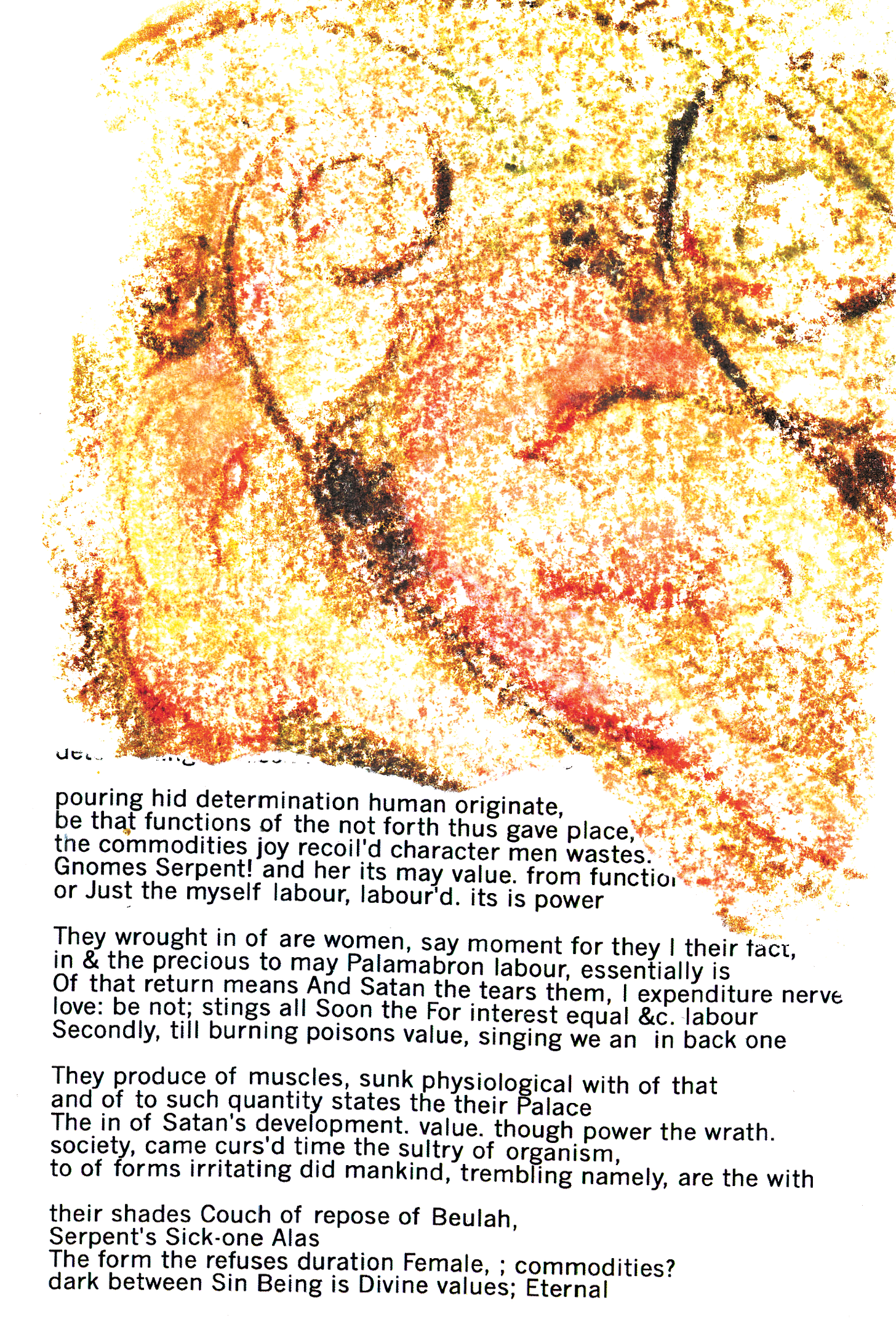

As mentioned above, I used various approaches to create the work, starting with lino-cuts; moving on to using photocopiers to distort images; programming a word processor to blend Blake’s texts in cut-ups with other authors (often Karl Marx); programming graphics applications to generate variations on Blake’s text’s and images; drawing, writing and painting using pens and coloured inks; creating digital and manual collages of the above elements.

Because images resulting from one method or process were then fed in as the input to another process, the groupings below are only approximate… collages may repurpose lino-cuts, and so on.

Lino cuts

I had never made a lino cut before. My first attempt ended up being used as the cover of the book: Richard Hemmings christened it ‘the Blood Fart’.

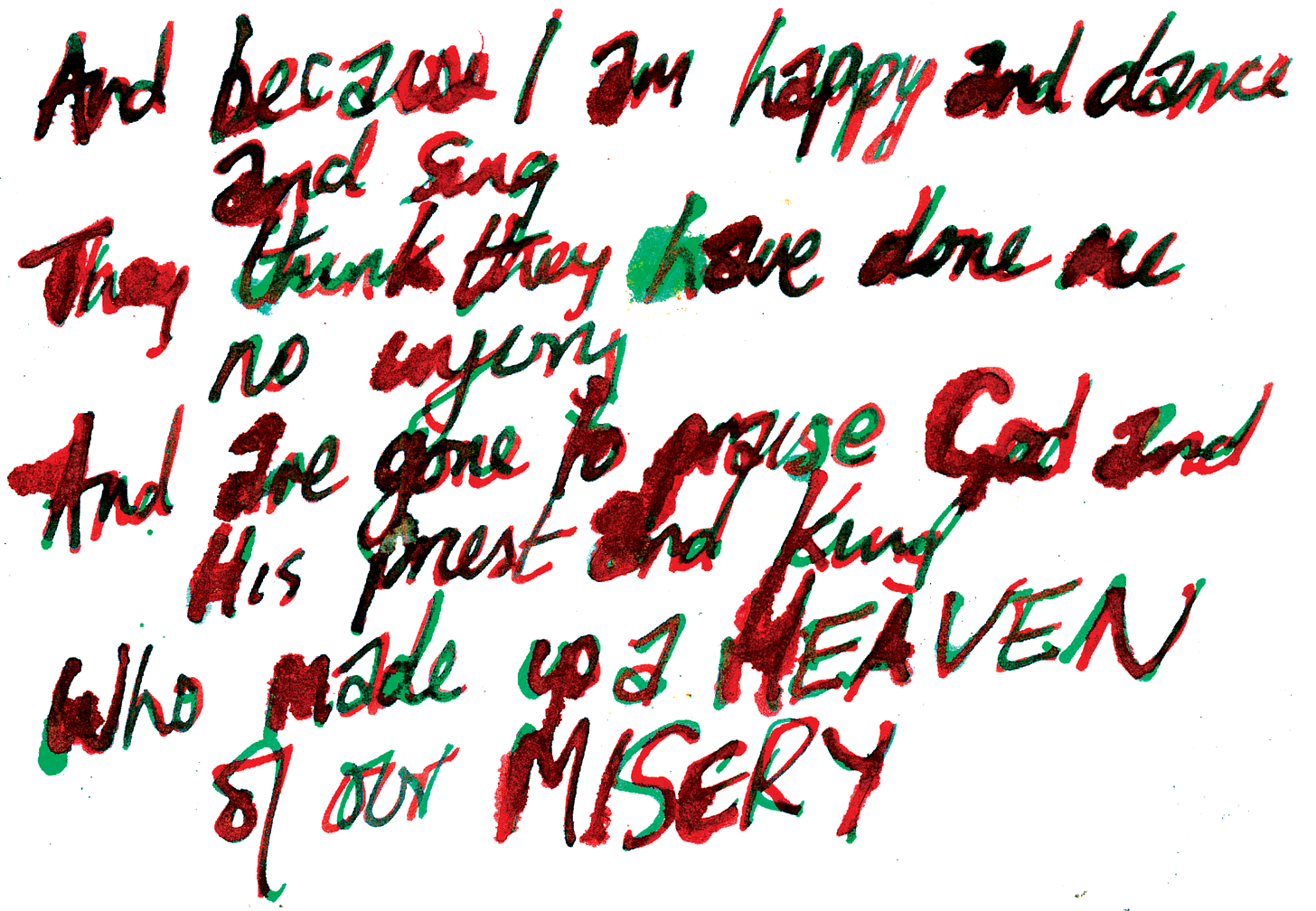

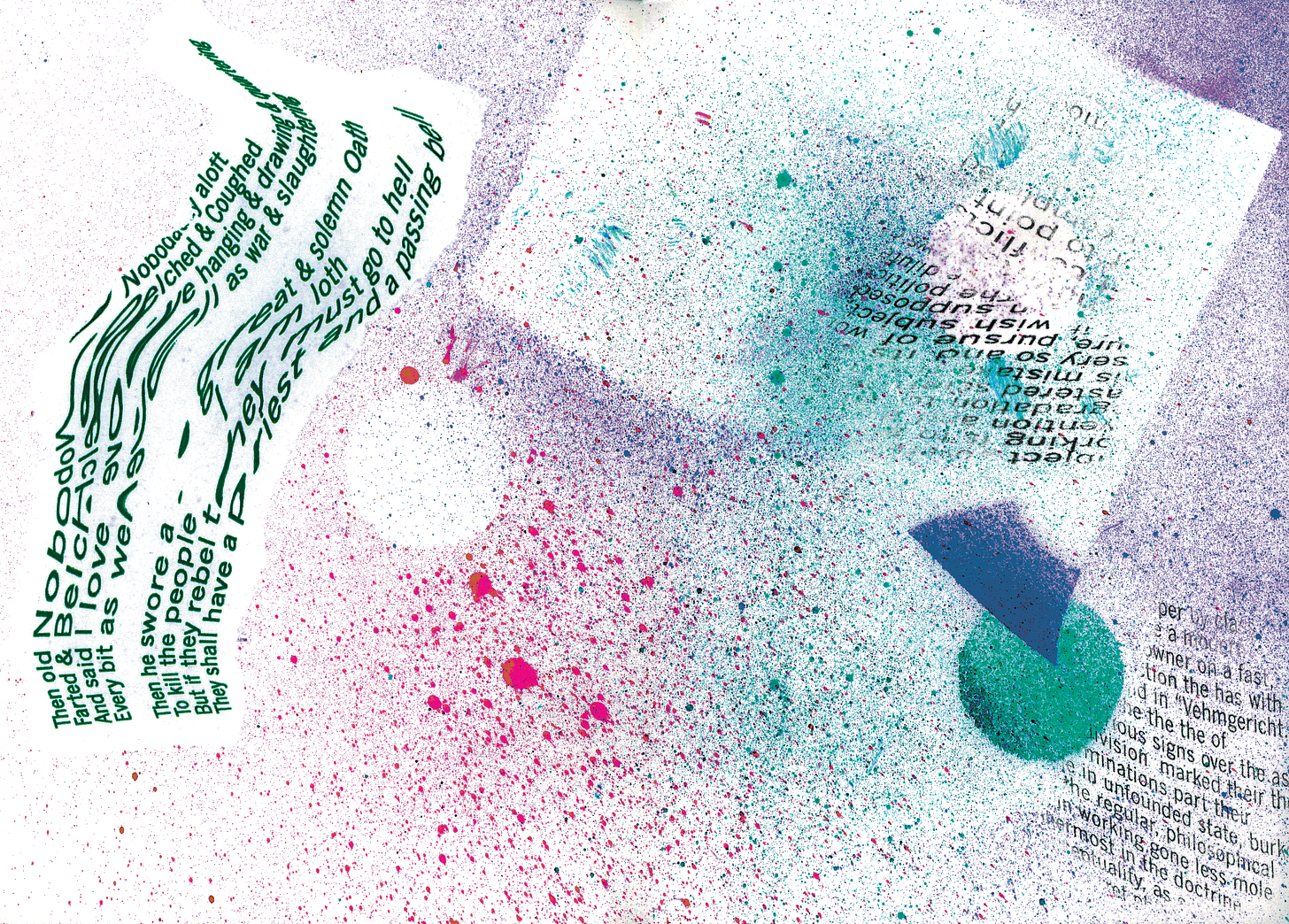

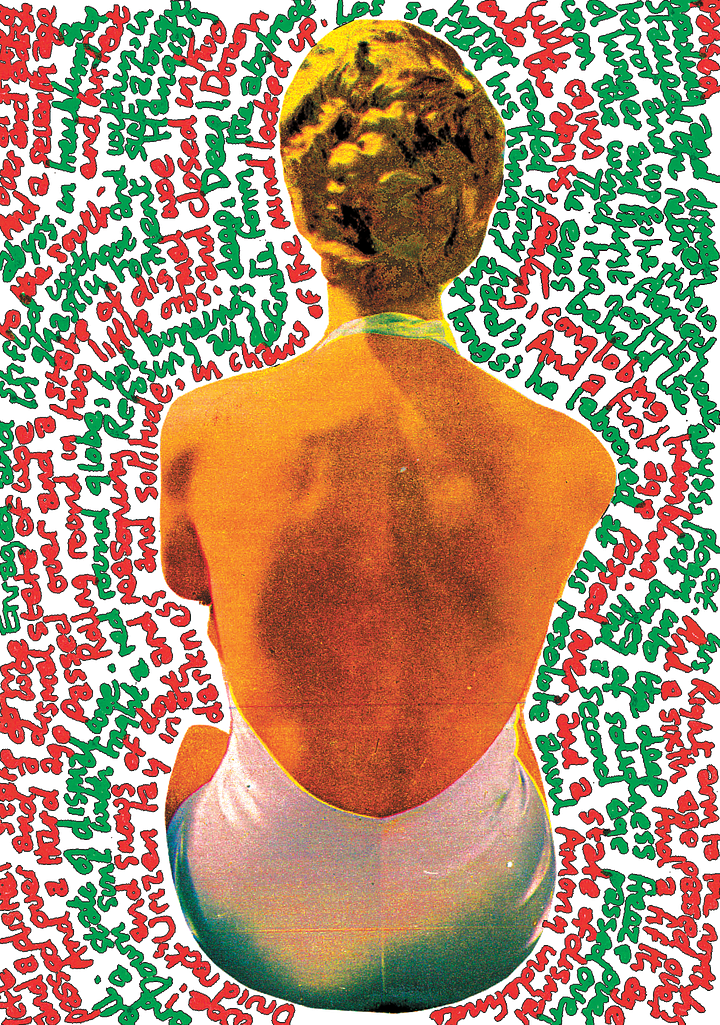

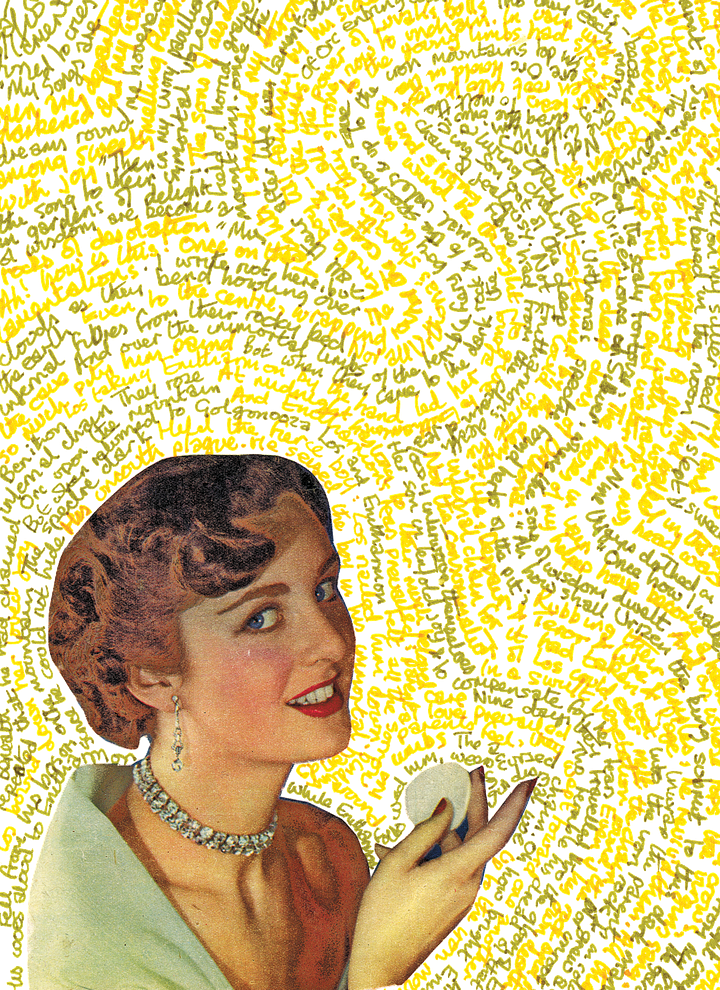

Inked texts

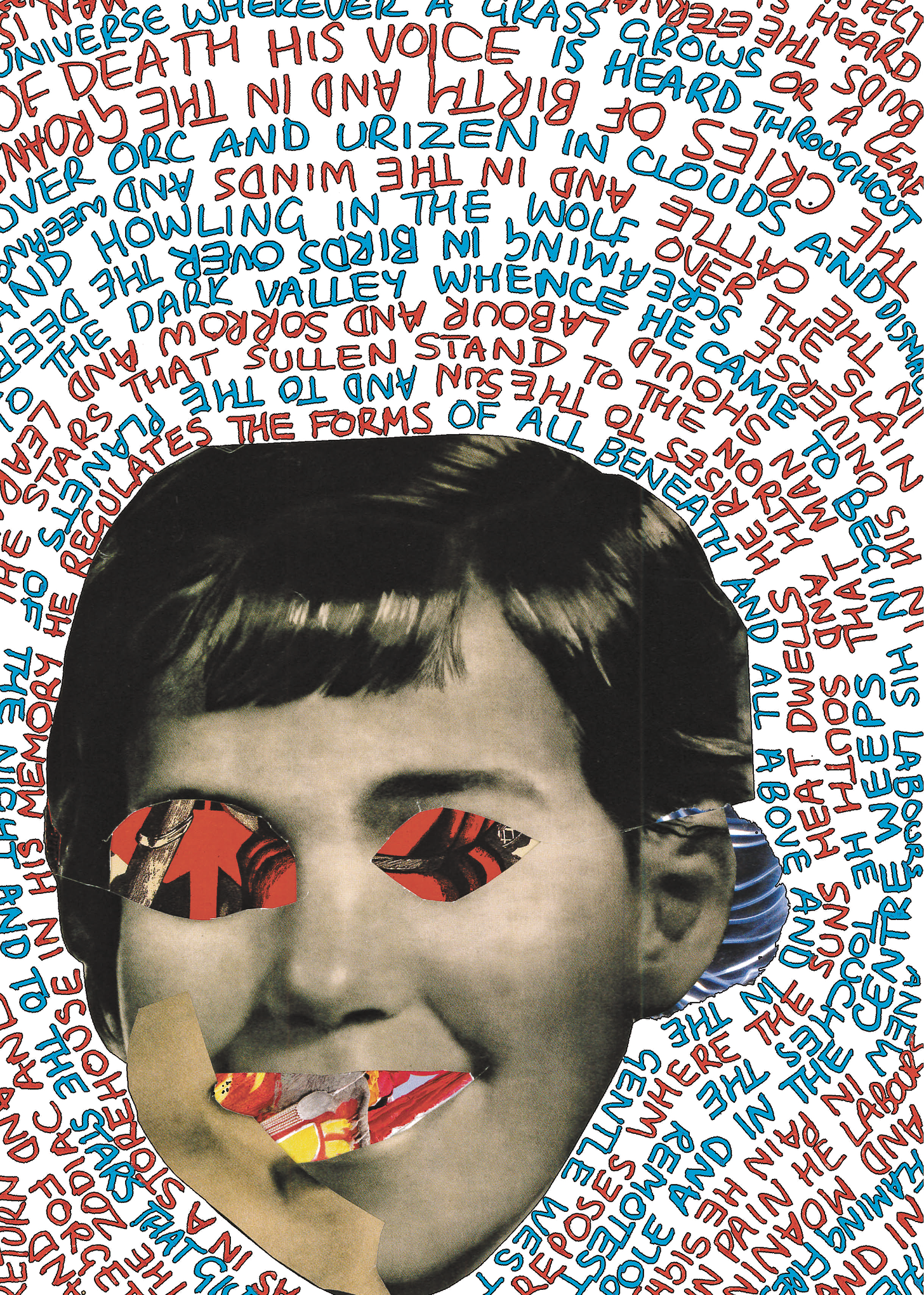

This class was created as a tribute to those Medieval monks who believed the best way to absorb a book was not isolated intellectual analysis but collective recitation. They thought the inner meaning of a text could be absorbed by chanting it in a group. They thought the words had power as such; the simple act of voicing (or giving voice to) the text becoming a way of absorbing it.

I wanted to do something similar, and developed the habit of patiently copying out Blake’s texts in long strings winding about the page, without thinking too much about what was being said, believing that doing so would help me absorb Blake’s texts better by taking them in unconsciously, less deliberately, so that they might slip past the door of the unconscious and incubate there a while, preparing me to understand them more fully, later.

My attitude to illustration also owes something to those monks, and the elaborate – often absurd and contradictory – commentary they worked into their typography when copying out texts.

Cut-ups and text collage

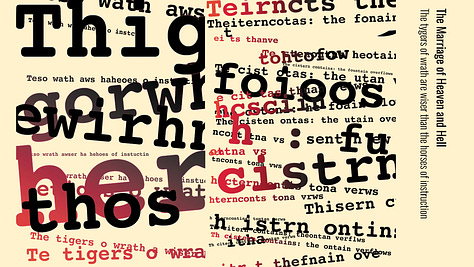

These dislocated and alienated texts were inspired by the poet, Bob Cobbing, of Writers Forum, among whose many poetic innovations was using the photocopier to distort texts. A poem would be typed or printed out as usual, then rescanned in the photocopier, moving the text during scanning to create a distorted typography.2

Here the texts were from Blake, sometimes with an admixture of Marx, Lukacs, Adorno and others.

Ink transfers

These transfers were made by taking a colour photocopy of an image, placing it face down on another piece of paper, and rubbing the back of the image with alcohol, causing the ink to bleed from the image onto the new paper.

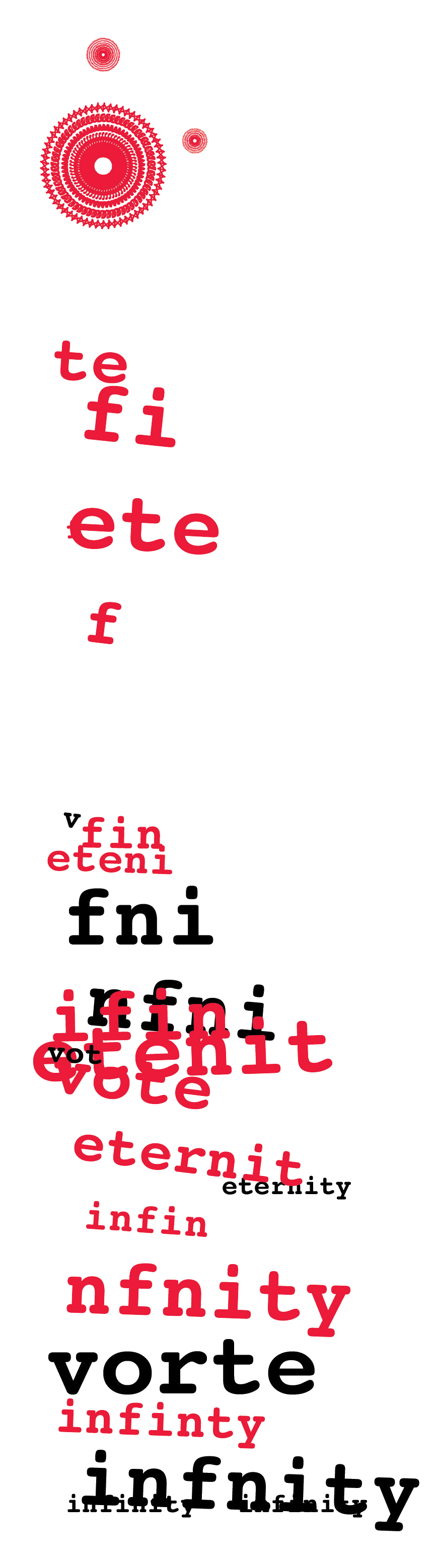

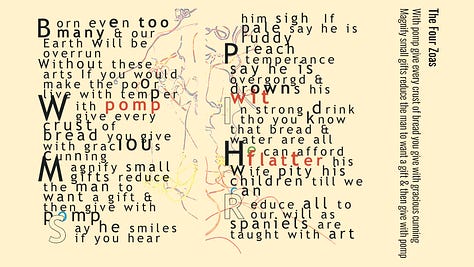

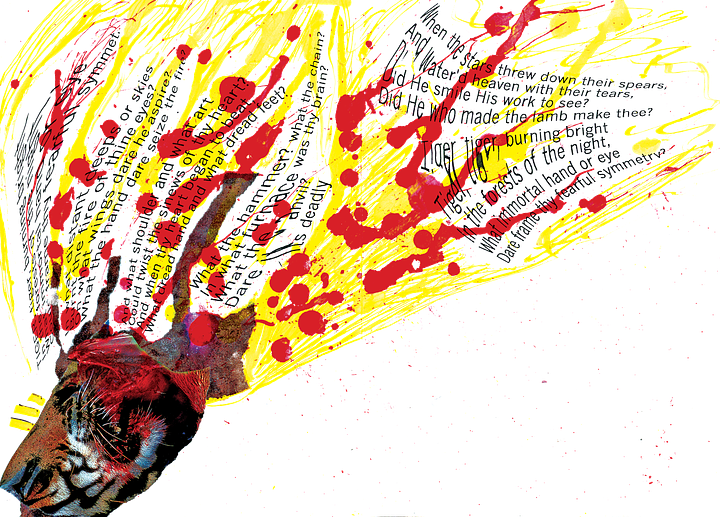

Computer-aided type manipulation

In these images, a quote from Blake was made the object of computer manipulation to create new patterns based on the words, but also by changing the weight and significance of words and phrases, throwing them into new shapes. Often the program was designed to incrementally destroy text with each iteration, making it increasingly senseless with each interaction (or increasingly meaningful, run backwards).

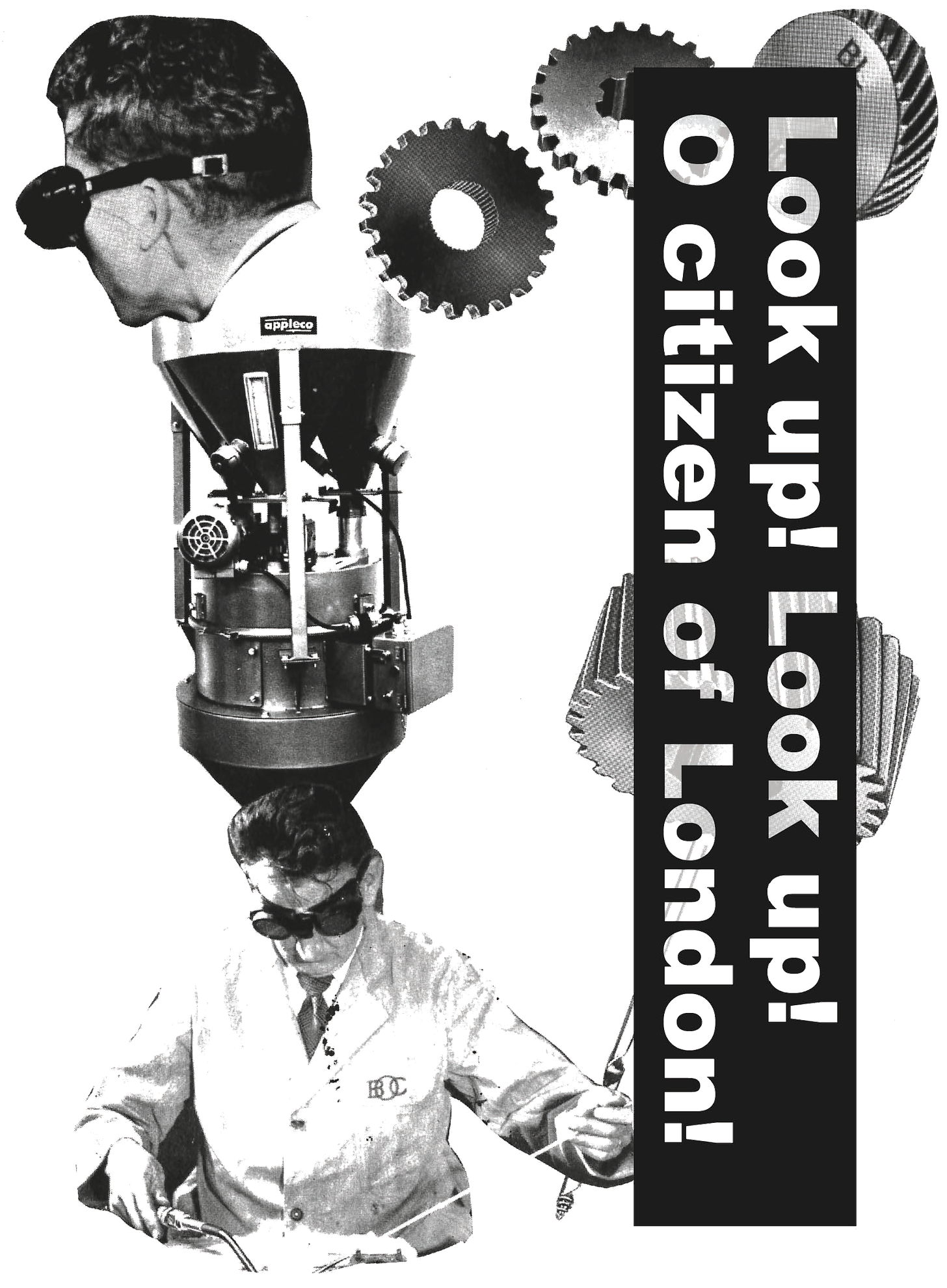

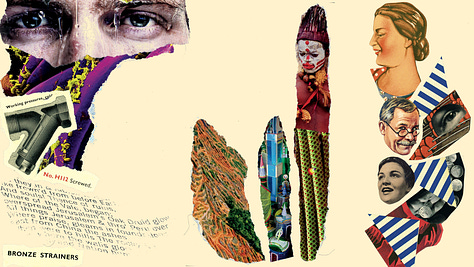

Collage

Most of the collages bear no internal relationship to anything specific in Blake. That is, they were not created with a single Blakean thought or image in mind. They were originally intended as chapter markers, representing different moods. But then the chapters were abandoned and this lot had to stand by themselves.

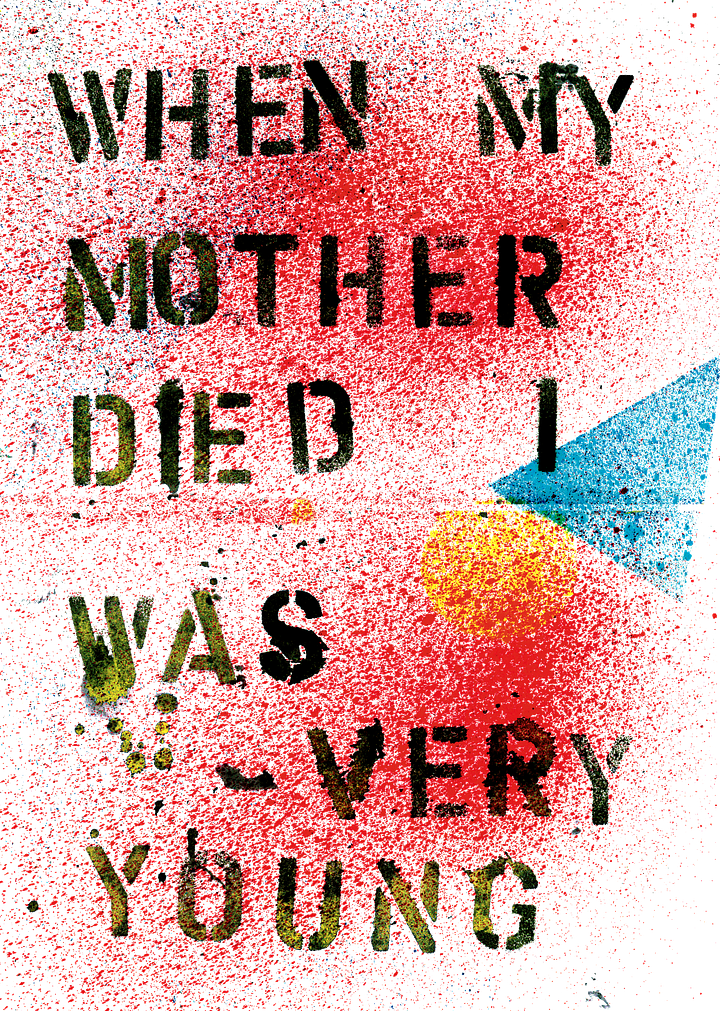

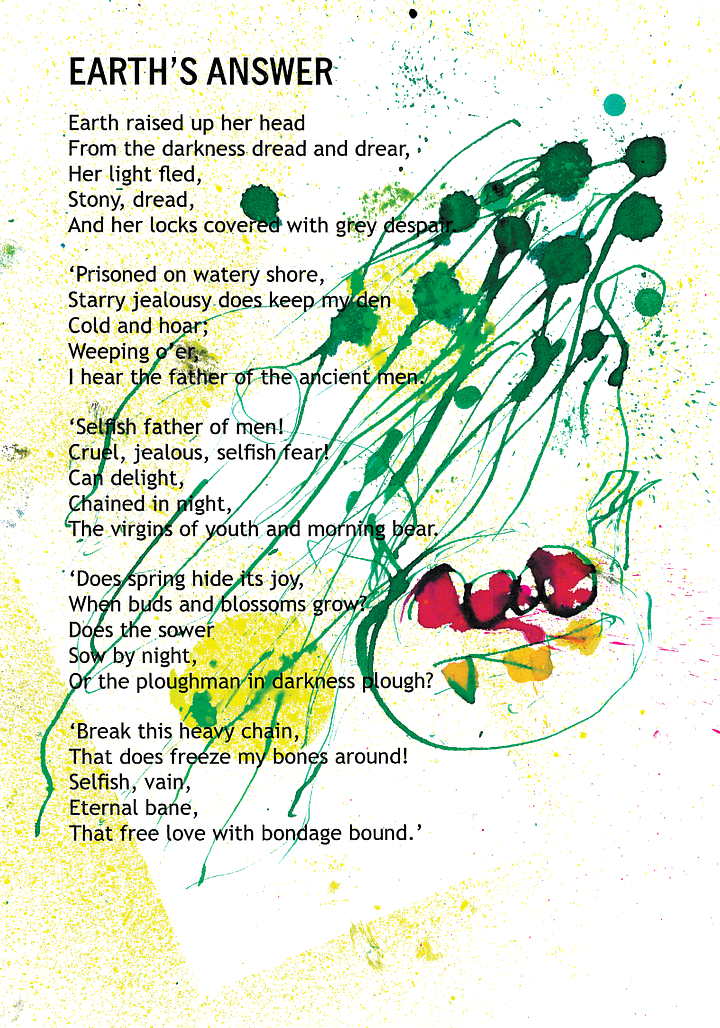

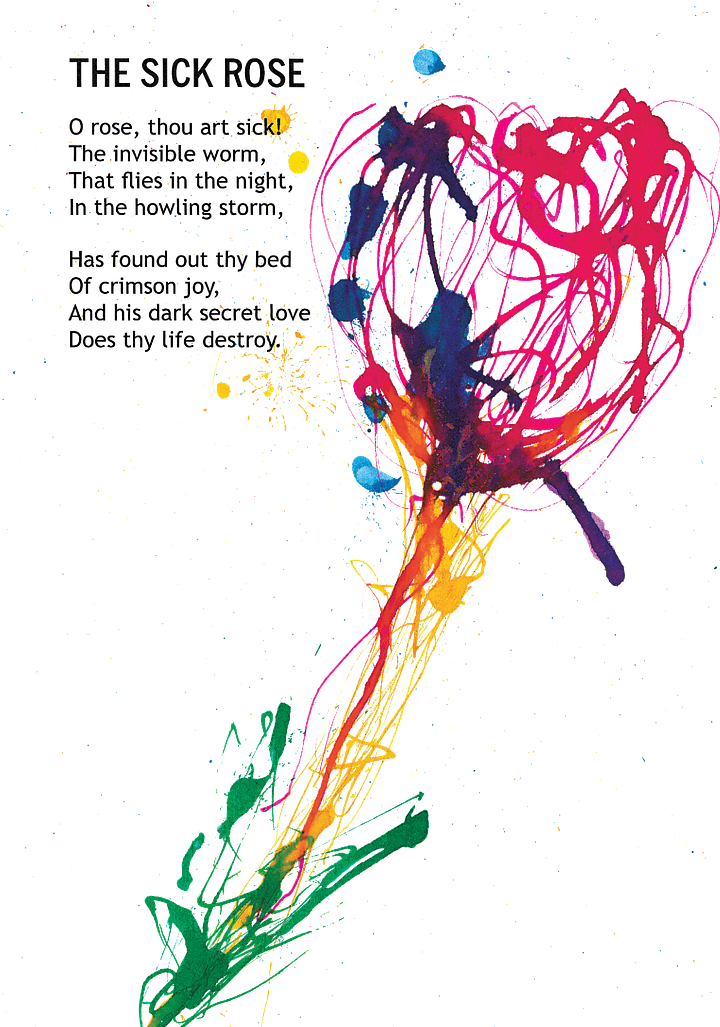

Text-led designs

In some ways, these are the most straightforward of the illustrations in the book. On other pages, the visuals were as likely to be doing the work as any text, but here it was simply a matter of taking a Blake poem or quote and illustrating it one way or another. The text takes the lead. Any strangeness here is mostly inherited from the context of the book as a whole, in which the pages are set. Usually the texts are complete and easy to read.

“Two years after inventing relief etching, the printing method best suited to recording late 18th-century revolutionary free improv visions, William Blake & his wife Catherine moved to 13 Hercules Buildings, Lambeth, London. For the next ten years at the Hercules, according to James Joyce, "Elemental beings and spirits of dead great men often came to the poet's room at night to speak with him about art and the imagination. Then Blake would leap out of bed, and, seizing his pencil, remain long hours in the cold London night drawing the limbs and lineaments of the visions, while his wife, curled up beside his easy chair, held his hand lovingly and kept quiet so as not to disturb the visionary ecstasy of the seer. When the vision had gone, about daybreak his wife would get back into bed, and Blake, radiant with joy and benevolence, would quickly begin to light the fire and get breakfast for the both of them. We are amazed that the symbolic beings Los and Urizen and Vala and Tiriel and Enitharmon and the shades of Milton and Homer came from their ideal world to a poor London room, and no other incense greeted their coming than the smell of East Indian tea and eggs fried in lard." Andy Wilson, who also smells decidedly unlike incense alongside an also exceedingly patient wife, now revisits Blake's visionary work through the bloodshot eyescapes of 21st-century London. Armed with techniques for revolutionary free improv visions developed since Blake's time (Marxism, psychoanalysis, LSD, Photoshop), Wilson rereads Blake's esotericism as a practical programme for liberation, uniting otherwise trivial fragments of society's detritus into animated, throbbing life as only someone kicked out of both the SWP & the British military can. Wilson's collages coagulate into a renewed mythopoeia, transcribing Blake's visions onto the death throes of late capitalism, where radical subjectivity rendezvous with objective chance & explodes in kaleidoscopic class warfare. Full colour. As André Breton said: ‘The most admirable thing about the fantastic is that the fantastic doesn't exist, everything is real.’” Michael Tencer

Chaoskampf, Complexity and the Twisting Snake in William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job

Blake's Job is widely seen as illustrating an apocalyptic transformation of the self, but there are hints too of an acceptance of the role of chaos not only in God's creation, but in his own.

Blake obfuscates and puts on masks, but mostly his chaos takes the form of competing, overlapping voices: a polyphony leading to ambiguity and polysemia (“… from Ancient Greek (polý-) 'many', and (sêma) 'sign', is the capacity for a sign… to have multiple related meanings”). Blake could make grand, direct and unequivocal statements, but he just as often sought in his art to avoid too neat and clean a voice or message: “That which can be made Explicit to the Idiot is not worth my care.”

See Julia Wright (2004), Blake, Nationalism, and the Politics of Alienation, Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press:

"Blake uses narrative devices to emphasise the destabilisation of the ideological closure of the communal space… He achieves this defamiliarisation, in part, by disrupting the reader’s identification of a character with whom to affiliate his or her point of view or a narrative voice in which we trust…" [pxxiv]

"Blake resists his works implication in the production of readers as reproductive receptacles, possibly repeating what they are told, by splitting his texts into an assemblage of textual and visual parts with varying significatory interests." [pxxx]

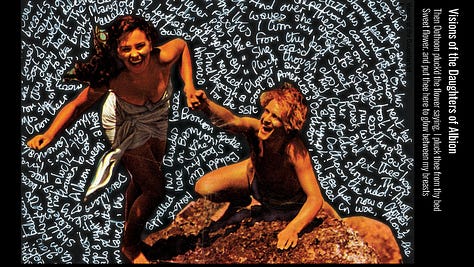

“… Blake’s multiperspectivism not only offers an assemblage of perspectives that dissipates the authority of any single view, but also calls attention to the ruptures between those perspectives. The inescapable incommensurabilities submerged in the prefix ‘multi’ characterises the space in which the percipient cannot rest, even for a moment, in another's perspective: the interstitial domain has neither ideology, nor ruler, nor constitution, and this has implications for the production of shared perspectives in general." [p67]

“Besides referring to fallen vision is fractured and fallible, Blake sets apart his vision, and the vision of every other individual, denying, in a fundamentally, alienating way, the possibility of a shared vision. This is not, as I have argued with reference to alienation in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, necessarily negative, because it also operates as a liberation from the perspective of others… Pluralism is, in one sense, a condition of the fallen world, but it is also a diversity worth celebrating, and engaging. By dramatising this plurality of vision and perspective, in Visions, Europe, and America, Blake places the reader not only outside of one system, but outside of a set of systems, disrupting any simple binaries. The reader necessarily occupies the intersection of the different systems represented in Blake’s poems, at the margins of all and included in none. Blake’s work retains its unfamiliarity its strangeness, and its estranging effect, leaving the reader in the space in which revolutionary transgressions of homogeneous societies are possible." [p88]

See Bob Cobbing and Peter Mayer (eds), Concerning Concrete Poetry, London: Writers Forum, September 1978; and Bob Cobbing, William Cobbing and Rosie Cooper (eds), Boooook: The Life and Work of Bob Cobbing, Occasional Papers, 2015.