William Blake's Universe: Blake at the Fitzwilliam

In this new exhibition Blake is shown alongside Europeans who also turned to spirituality in response to war, revolution and political turbulence.

In 2019 there was a huge, and hugely popular, exhibition of Blake’s works at The Tate in London. This was something of a generational event, a rare chance to see a major exhibition of Blake’s work in the flesh. I visited several times and was moved by many things, but sometimes simply by being near images that are such an important part of my life. Everyone judged it a success.

The new Fitzwilliam exhibition is different in tone, an earnest young brother to the blowsy Blake who did the Tate show. The intended effect is not shock and awe, but rather the staging of a carefully posed challenge to the popular view of Blake as totally sui generis – as completely original as he was thoroughly idiosyncratic.

T.S. Eliot, being a jerk, but perhaps also reflecting the generally low level of understanding of Blake at the time, said Blake lacked "a framework of accepted and traditional ideas that would have prevented him from indulging in a philosophy of his own", and that he suffered from "a certain meanness of culture."1 Eliot sees Blake as a kind of exotic art brut hobbyist whose ravings astonish and transport us but have no bearing beyond themselves.

But as we now know, Blake certainly had roots in an established culture, drawn from scattered traditions of religio-political dissent, albeit that it was a demotic culture, and therefore invisible to Eliot. We know too of his friendships with fellow English artists James Barry, Henry Fuseli, Samuel Palmer and John Flaxman, and of their artistic exchanges, borrowings and influences. Blake’s purely intellectual interests do seem to lie almost exclusively with the Bible and related enthusiasms, but all the same, he was widely read and his interests stretched at least as far as Jacob Boehme – the mystic ‘founder of German Philosophy’, according to Hegel, and to that extent a great influence on the German Idealism that went hand in hand with Continental Romanticism.

If he was out of step with mainstream art, Blake nevertheless clearly felt himself a comrade of sorts to at least a small number of his contemporaries. The purpose of this exhibition is to try to widen that circle of comradeship to include a handful of European Romantics who are argued to have responded to the same crisis with similar means to Blake, namely visionary art, thereby making them his peers, albeit that they would have been as unknown to him and he was to them.

The idea is that Blake was on a parallel trajectory to others who reacted to the trauma of their times by turning towards the spiritual. Chief among those Blake is compared with here are Casper David Friedrich, Philipp Otto Runge, and Asmus Jacob Carstens, alongside those already connected with Blake at home – Henry Fuseli and John Flaxman in particular (nothing in the exhibition explains why the Europeans were all known by three names, and the Brits get only two.) The entrance to the exhibition features (mostly self-) portraits of the featured artists lined up on one wall directly opposite corresponding portraits of Blake by Flaxman, Catherine Blake and John Linnell… Game on! You get the idea.

The curators (David Bindman, author of several key scholarly texts on Blake’s art, and Esther Chadwick of the Courtauld Institute) make their point well: the failure of the French Revolution to introduce universal liberation led some artists to interrogate reality more keenly in search of its spiritual core, which they might then preserve against the buffeting of time. This they did by drawing on classical art and then the Gothic for models, the latter choice often being fanned by romantic nationalist thoughts of challenging the classicising ruling classes from a plebian, nativist standpoint. This, at least, seems to be part of Blake’s thought on the matter, with his dismissal in later years of the Greeks and Romans as “silly slaves of the sword.”2

On the other hand, despite the similarities, Blake’s art still exists at a marked angle to those he is being compared with. Blake famously defended the idea that art should be full of definite lines, in accordance with the imagination; “the more distinct, sharp, and wirey the bounding line, the more perfect the work of art;” “Nature has no Outline: but Imagination has!” Nevertheless, his works pulsate with an autonomous life and energy that threatens all outlines and boundaries. Very little about it, visually or conceptually, in terms of his myth, is geometrical or tidy.

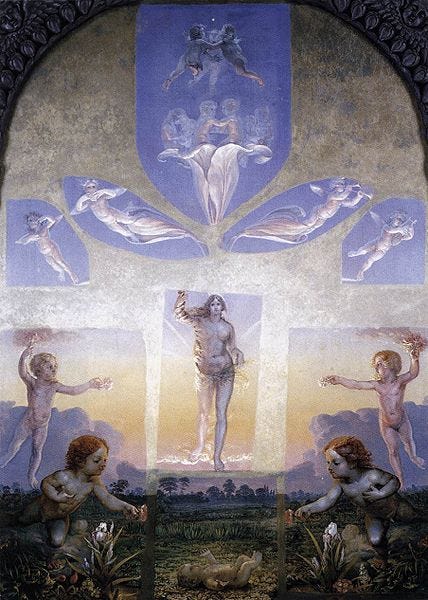

His European peers, on the other hand, often recourse to symmetries expressing an almost Enlightenment view even of the spiritual, connecting symbols into stable ratios and balances in the interests of (esoteric) science. One of the most striking sections of the exhibition is the small set of images illustrating Jacob Boehme’s works, by the great Behemist artist, Dionysius Andreas Freher, and others. The images are hugely engaging and suggestive, but they are as essentially geometrical as the alchemical diagrams that must surely have inspired them. They are what they seem to be; spiritual diagrams.

This isn’t true of all the non-Blakean art on display. It certainly isn’t true of Caspar David Friedrich’s landscapes, though their symbolism is nevertheless often as clear as any geometrical formula. Despite this, his series Seven Studies in Sepia (The Ages of Man) is one of the highlights of the show, and as close as the Europeans here get to the sheer strangeness of Blake in his pomp, albeit that Friedrich’s symbolism is almost literally-minded. His juxtaposition of two skeletons buried in stalagmites with two angels praying above the firmament is particularly lovely, partly because he is using sepia instead of his usual shouty, chiaroscuro. No matter what the similarities to Friedrich, Runge, et al, Blake’s mythos and its representations alike are unstable structures, likely to blow up or collapse at any point, easily toppling over into a sort of sublime incoherence, while his counterparts perhaps have a more reassuring, manageable view of the spirit.

Blake’s uniqueness stands despite the undoubted convergence on display. Jonathan Jones thinks that by making comparisons with the European Romantics, not only does the exhibition undermine Blake’s individuality and uniqueness, but Blake even emerges as a lesser artist in terms of the comparisons made. Jones perhaps misses the bombast of the Tate’s blockbuster show and resents the comparison that is the theme of this show, writing any similarities off as insignificant effects of the general Romantic sensibility of the era.

It is not worth spending time dismissing such a transparent misreading of the images and their language. Enough to say that the selections of Blake here, including plates from Europe, America, the Illustrations to the Book of Job, Paradise Lost, and Blake’s illustrations to Stedman’s tract against slavery, Narrative of a Five Years' Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, all burst from their rag-paper pages to seize the viewer’s attention in a way the Europeans rarely muster.

While I think the curators have done a good job of making the argument they want to make, they could have made things easier for newcomers to Blake with more contextual and biographical information. The accompanying exhibition catalogue has useful essays on different aspects of the argument, and Bindman’s essay there, ‘In the Present: Europe in Flames’, does a good particularly good job of setting the scene: perhaps it could be printed as pamphlet for those wanting more context on the day.

The corollary of this criticism is that, on the bright side, there is no hand-holding or cheerful didacticism here. Visitors are left to make up their own mind about the issues raised rather than having answers fed to them. This is a shame for Jonathan Jones, who it seems was left high and dry by the lack of fanfare, but mostly this is a bonus.

As well as being a notable Blake scholar (author of the definitive catalogue of Blake’s visual art, The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake), curator David Bindman has particular expertise in the treatment of racism in European art (being the author of both Race Is Everything: Art and Human Difference, and the five-volume series The Image of the Black in Western Art.)

He must have drawn on this when putting the issue of Blake’s anti-racism in context when captioning the display of ‘The Little Black Boy’, from Songs of Innocence. Bindman addresses the question of the apparent contradiction between Blake’s anti-racism with some of the prejudiced assumptions of the poem. Mostly this boils down to the fact that, according to Blake, even in paradise the black boy, though now ‘free’, is still only an aide and playmate to the white boy, not his equal.

Nothing is particularly challenging about the issue: Blake was anti-racist, but lived some centuries ago. and his thoughts in some of their details simply reflect his times. The exhibition deals with this, but the Guardian reviewer concludes that it means Blake was “clearly a racist”, and that this discovery represents “a crisis in our relationship with Blake for it is so bound up with the belief that he’s a radical, a good guy, on the left.”

As with the issue of Blake’s supposed inferiority to the other Romantics, this argument doesn’t deserve much of a response. I’ll ignore the question of whether it makes sense to read Blake’s poem as a transparent expression of his personal beliefs, rather than those of the ‘little black boy’ who mouths those opinions, though that just raises further issues.

Let us assume that these were Blake’s views. Racial prejudice is simply wrong, whatever the context, but there are different kinds and degrees of wrong, and it is precisely the context that defines the political impact of being wrong, which is what we should care about; and in Blake’s time, the political impact of taking the positions he did was such as to leave his radical and libertarian credentials intact.

If there is a contemporary ‘crisis in our relationship with Blake’, it is not because we overestimate his radicalism, but rather because of the temptation to downplay his radicalism in favour of a more popular, clubbable image of Blake as a (loveably cheeky, though probably a bit racist) cockney Little Englander… a Brexit Blake.

What is most annoying about such anachronisms is not the slight to Blake’s reputation, which will survive intact. E.P. Thompson spoke of the “enormous condescension of posterity” in how we judge our forebears, and we can speak too of a corresponding presumption of history in making such easy and unmediated judgements about the past. Such judgements assume that the present – the base from which we are doing the judging – is itself in a fit state to confidently judge anything easily or transparently.

Sibylle Earle, chair of the Blake Society, has written an open letter in response to Jonathan Jones's review, which makes all the salient points about this presumption. I support the letter, but think we should take up Jones’s challenge to review our notion of Blake as a radical. We need such a review not primarily to question again the extent of Blake’s radicalism, but to question instead current popular perceptions of Blake to see where they distort our image of Blake precisely by underplaying that radicalism. We deserve a better Blake than we have been getting.

In the meantime visit the exhibition if you can. Quite apart from the questions it poses, there are major and minor pieces by artists of note as well as many Blake treasures on show. For Blake scholars, there are a few exciting, previously unseen items, such as an early version of his Laocoön, and a new copy of Joseph of Arimathea.

Like me, you may also absorb something about how the political climate in post-revolutionary Northern Europe led such a diverse group to practice such overlapping visionary arts, mixing in romantic nationalism and the Gothic. If there are problems with our perception of Blake, none of them are at play in this exhibition, which raises valid questions about Blake’s relations to various other artists, but does so in a way that avoids easy answers.

Also, there is a Jacob Boehme pop-up book as part of the exhibition, illustrating Boehme’s entire cosmic stack, which you must see, and which someone urgently needs to republish along with the collected illustrations of Dionysius Andreas Freher.

T.S. Eliot, Selected Essays, NY: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1960, p.279.

I don't wonder what the "certain meanness of culture" was that Eliot spoke of about Blake. I think of Blake as having Gaelic tempers and manners. These manners don't jibe with the Franco-Prussian manners of the English upper-class. Always be ready to speak your mind, and everyone's going to know you've got a lot of Gaul.

There is a resonance between the German mystical tradition and British Romanticism, and I'm glad you feel it. German poetry never stopped being about nature. Herman Hesse was a 20th century German mystic writer. His novels and poetry are great. Both Blake and Hesse were interested in Eastern mystical traditions and they are my two favorite writers...the two that I've read the most exhaustively. Both Blake and Hesse led me backward in time, to their antecedents. I believe this was what Blake intended by winding the thread into a ball. Blake's thread leads back to Milton and the symbolism of classical poetry. Hesse leads back to ancient Taoism. Lao Tzu and Chaung Tzu. I Ching, as well as to the German tradition of Paracelsus and Boehme (among many others).

Thank you for your posts. I enjoy them very much. This short story by Hesse is perfect. https://www.alastairmcintosh.com/general/resources/2008-Hesse-The-Poet.pdf